Some years ago now, on a tour of the Highlands. Whilst walking a quiet lane, some ten miles south o replied f John O’Groats, I came across an old, bent man. He carried a pack on his back, a shovel in his hand, and stood next to a large pile of ballast. As I passed I bid him good morning, tipping my cap. ‘Mornin’’, he.

Looking beyond the man, I noticed he had left a thin trail of sand behind him. After a moments consideration it occurred to me that the old man had shovelled the pile of ballast down the lane by hand. One shovel over the next, all the way to where we now stood.

I turned back to face him. ‘ Excuse me’, I said, ‘I hope you don’t mind me asking, but have you moved that ballast by hand? ‘I have sir, yes’, he replied, in a broad West Country accent. ‘This ton, the one before it, and indeed, the very one before that. All by hand sir, one shovel over the next’. Pondering for a minute, looking down the lane and taking a few steps back along the trail of sand, I placed one hand in my jacket pocket. With the other, I removed my cap and scratched my head. ‘I’m not sure I understand’, I said at last.

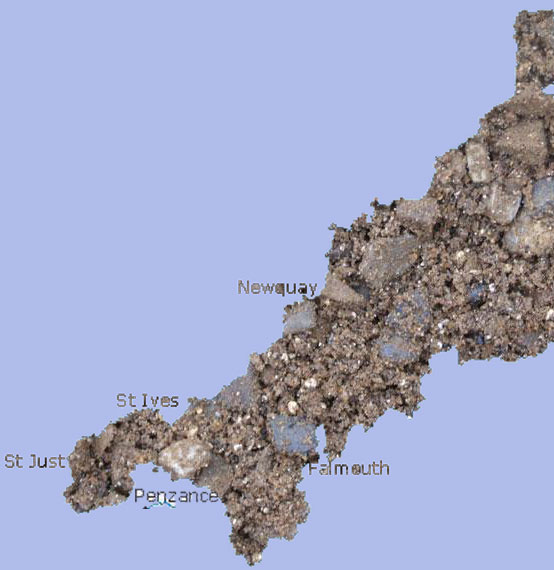

Steadying himself by parting his legs slightly, and leaning his crossed arms on the handle of his shovel to take his weight, the old man prepared to tell me the story he had been telling his whole life. ‘It all started with my grandfather, you see? He’d come back from the great war, ‘by the skin of ‘is teeth’, as he used to say. Just old enough he was to catch the last of the action, and not too impressed by it was he neither. He’d seen some terrible things, and like so many others believed that by experiencing these horrors he was paving the way to a better future for all of us. The only thing was, that the bright future didn’t come to nothing. By the mid thirties down in Cornwall, where he were from, Penzance, it were, people were out of work, and hungry. Starving for their meals they were, and a great sickness carried a lot of ‘em away, my Grandmother and two little ones among ‘em. My grandad, he were left with a twelve year old son, the clothes he stood up in and a whole load of grief.

After the grieving had consumed him a while, one morning he lept out of his bed and declared to my dad that they were leaving. He was to pack a bag and spend the morning saying goodbye to all those that meant anything to him. ‘Where are we going dad?’, my dad asked. ‘Never you mind my boy, I’ve found us a purpose’, my grandad told him, bundling him out the door of their tiny cottage. The home he was to never see again.

This purpose my grandad had found took the form of a ton of ballast and two shovels. You’ll be knowing ballast of course?‘ The man bent forward and picked up a handful from the pile in front of him. ‘Tis a mix of sand and gravel. Stones dredged up from the bottom of the sea. Sometimes if you look among it, you’ll find shells and little polished gems, like beads’. The man became wistful, dreamlike as he let the ballast fall between his fingers. He looked as if he were considering a lover long passed or a lost child. ‘Mostly used in concrete’, he said sharply, throwing the last of it, back on the pile, snapping us both out of a trance.

‘I see’, I said. ‘There must be an awful lot of it.’

‘That there is’, he replied. ‘I’ve seen over five hundred ton of it myself, and there’s only one of me. Goodness only knows how many other people there are. Got to be billions by now, I’d wager.’

‘And some’, I said not wanting to sharpen the mood with figures and statistics.

‘Anyways’, the man continued, straightening his back. ‘My grandad he shows my dad this ton of ballast down there in Penzance, all them years ago, throws him a shovel and says, ‘this is wantin’ to be delivered to John O’Groats’. ‘But I don’t know who that is’, replies my dad. ‘It’s not a who, it’s a where’, says my grandad, and it’s that way’. He points up the road, away from Penzances.’

It took me a moment to realise what the man was telling me. When the penny dropped a broad grin spread across my face and I laughed out loud. ‘So your grandad, in order to make sense of loosing his wife, two small children and his lively hood, decided to shovel a ton of ballast from Lands End to John O’Groats’.

‘Twern’t Lands End, it were Penzances’, the old man corrected me. ‘Lands End is another thirty miles west, so I’m told’.

‘Yes, yes, of course. You are right’, I said regaining my composure. I was annoyed with myself for interrupting. ‘Please go on, what happened next?’

The man, once again, leaned forward on his shovel before continuing. ‘All his friends they did come out to see ‘em off. Some thinking he’d lost his mind, saying it weren’t fair on the boy, and all that’.

‘What did he say to that?’ I asked.

‘My father says to I, many years later, after grandad had passed, that he’d been born to the mines, and if he hadn’t been shovelling above ground, he’d a been shovelling below ground. So those London money men, who didn’t see no sense in running the mines, had done him a favour in the long run. Seeing as he’d had a chance to see a little sunshine in his life. ‘A man will be working whatever’, he said, ‘and a woman too’, he was careful to add, ‘so I might as well be throwing this ballast in front of I, as doing anything else’.

We stood in silence for a minute. It was a cool spring morning and in the trees above us, the birds sang. I couldn’t believe the story, and began to think the man was some sort of practical joker, who had set up this elaborate ruse to trick passing tourists, for his own amusement. ‘You’re having me on?’ I laughed. ‘This is a joke you’re playing on me’.

‘I swear I ain’t’, said the man staring up the road. ‘That story is as true as the day is long. Or as sure as the sun shines in the sky above us’. At which point we both looked up. Sure enough the weak Scottish sun was just peaking out from behind a cloud. ‘You can follow this trail of sand all the way back to Cornwall if you’ve a mind to’.

Looking down the road, then again at the man, I shuffled on my feet, wanting to believe him. I took a few steps, stopped, then came back. Standing directly in front of the man, I asked, ‘If it was your grandfather and your father who set off from Penzances, how?…. where?’ I struggled to phrase the question. ‘Where on earth did you come from?’ I finally managed to blurt out.

Quite clearly used to recounting his tale and seemingly with all the time in the world to tell it, the man took a tobacco tin from his pocket and slowly rolled himself a cigarette. Placing it in his mouth, he took a box of matches from his pocket, lit the cigarette and exhaled a plume of smoke that engulfed him entirely. After waving the smoke away so I could see his face again, he looked me in the eye and said, ‘I’m glad you’ve asked me that, ‘cos it’s a good story.’ I folded my arms across my chest and listened.

‘The two of them had been shovelling their way North for the best part of six years. Picking up bits of work here and there. Selling ballast to folks for driveways, paths, that sort of thing. ‘course the pair of ‘em is fit and strong and they had no shortage of female attention along the way. Stopping for a while, here and there, as they did.

It happened that right up there on the top of Dartmoor, near Widdecombe, my father got friendly with the farmers daughter and one thing led to another, as they do. Three months after my grandad had managed to drag my dad away, my ma discovered he’d left something behind.’

‘Ah, I see’, I said.

The old man took another deep drag on his cigarette, before going on. ‘Now, my ma, she was still keen on my dad but, well, to be honest, she was already promised to the man who raised me. Not wanting to cause any upset, she didn’t see the sense in telling no one about the bit of fun she’d had, and went ahead and married the other chap. ’

‘That still doesn’t explain how you got to be here.’ I said, pointing at the road between us. ‘I was just coming to that. You can’t be in a hurry with a good story.’ He was right, I was becoming impatient. ‘I’m sorry’, I said, ‘in your own time.’

‘We lived happy up there on the moor. Tending the sheep and growing whatever food we could. My stepdad was a gentle man, and kindly, but when I gets to twelve-year-old, I starts to become irritable, like my feet constantly itching. My ma, she sees this, like a mother will and she says to her husband, ‘that one’ll be away soon enough, you mark my words’. He didn’t say nothing, knowing my ma to be right about most things, save sheep and ditches.

Well, by the time I were fourteen, I were clawing at the walls, driving ‘em all mad. Desperate to get away and see a bit of the world beyond that old farm. ‘Did you run away?’ I asked. ‘Didn’t need to’, he replied. ‘One night I heard raised voices coming up through the floor, which were rare in our house, seeing as they understood each other so well, so I knew something was up. Next morning I got up, went down for my breakfast, to find my ma alone in the kitchen. She broke the news to I there and then. The man I had been calling dad this whole time, weren’t my dad at all. Turns out my dad didn’t know nothing about farming, or ditching, or sheep or none of that. He was the son of a Cornish miner, most likely shovelling a ton of ballast towards the north of Scotland. If I had a mind too, I could head north, asking along the way, I might find him.’

‘And that was that?’ I asked. ‘Near enough’, he shrugged and threw the end of his cigarette on the road. ‘I packed a bag, says goodbye to my family, kissing my sisters and the baby. Shook the hand of the man who had raised me, hugged my ma and, after checking my compass, headed north to find my dad.

It wasn’t that easy mind. The world is a lot more empty and a lot more full than I had imagined before I left. I encountered many strange, wonderful, difficult and beautiful times along the way. Asking in the pubs for news of the pair. I heard no end of stories, the pubs being the place for ‘em. I found work in some, trouble in others. Songs and singing. Even a bit of love from time to time. There was a while I thought I might find some young bugger come looking for me, but it wasn’t to be.

Eventually after seven years of looking, I caught up with them. They’d made it to Derbyshire by then. Deep quarries and hills it is. Air as fresh as that I’d left behind. High too, it felt a little like a home coming. Arriving up there to the welcome hand of my dad.’ A tear began to well in the old man’s eye as he recalled the scene. ‘That was some moment’, he went on, ‘seeing them, seeing me. We all looked the same, but for me having my ma’s eyes. Them carrying the celtic dark hair and blue eyes. Me looking through these old chestnut brown eyes of mine. ‘What happened then?’ I asked, ‘How did they take it?’ ‘It was no big shock to ‘em, me arriving like that, I just slipped in to the rhythm of things. They teased me some for not thinking to bring a shovel, but grandad soon found me one from some place or other and off we went. ‘It were suprising’, my grandad said, ‘how much quicker the ballast moved with some fresh muscle throwing it about’.

Those years, with the three of us, they just flew by, but my grandad he was getting on a bit by then and it weren’t five winters passed before we lay him in the ground. My dad took that hard. Seeing as they had been through so much together. I comforted him as much as I could and we determined to finish job and deliver a ton of ballast to John O’Groats. Twenty odd year, my dad and I shovelled north. Having adventures along the way. We laughed and sang. Drank and fought. Earned money, made friends, took lovers and kept moving. Driven on by all the miles behind us and the promise we’d made my grandad.

The life of the travelling man though, is hard. It takes a lot of effort to keep the rain off your shoulders, snow out your boots and the sun from drying you out. It was the boarders and the Scottish low lands that did for my dad. We settled for a month or two in Berwick, and, as he rested he faded away. We’d met an old couple. Put us up nice and cosy they had. Fresh eggs in the morning, as well as bread and milk. We felt like prince’s, we did. To my mind, though, it were the comfort that killed him. Not that I’m complaining mind, just saying. I’ll always be grateful to those kind people. It was only when we stopped there with that hot water and a soft bed each that we realised how tired we were. My dad just couldn’t find the strength to go on. I promised him, just like we’d promised his dad, that I’d go on and deliver the ballast myself, and three days later we buried.

I didn’t hang about long after the funeral, seeing that the comfort could easily trap me. After seeing for a fresh ton of ballast to be delivered, I made my thankyous and goodbyes, and checking my old compass, just as I has all those years before, only this time heavy with grief, headed north. And here I am, these ten years later, not ten miles from John O’Groats, and all that has meant to three generations of us.’

I nodded as I took off my cap. ‘That is quite some story’, I said. Emotion rolling through me, as I looked at the old man through fresh eyes. ‘No more interesting than your own story, I’d wager’, the old man replied, as he settled himself on his feet, readying himself to hear how I happened to be in the north of Scotland. ‘Oh, no, no’, I laughed, waving him off. ‘You’ll not want to hear that. Tell me though, what’ll you do, when you get there?’ Chuckling lightly, looking up at the sky, the old man replied, ‘That is something I have thought long and hard about. I have heard though’, he said, picking up his shovel, sliding it across the tarmac, under the ballast and up, to lob the contents over the pile in front of him. ‘I’ve heard there’s a lady in Penzances, wants a path laying.’ His laugh echoing off the trees.

Ben Greenland

.