A reflection and review by David Erdos on

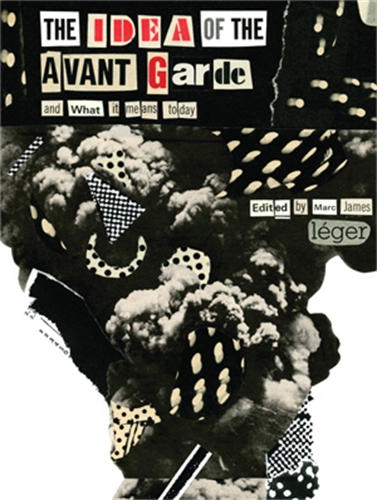

The Idea of the Avant-Garde and what it means today

(ed. Marc James Leger, MUP, 2016)

In the current crisis of faith, liberty, truth and the fallibility of virtually every institution and belief system in which we have previously invested, perhaps the only means of survival and expression lays in the creation of a new language with which to deal with the fallout and resultant issues involved. In this vital, new publication from Manchester University Press, editor and Canadian scholar, Marc James Leger presents an array of voices reflecting and proselytising on the uses and relevance of the Avant-Garde as the only legitimate force and means of expression that we, in a rapidly consolidating right wing world, now have left.

From Seminal critic Laura Mulvey’s essay on Mary Kelly’s installation, The Ballad of Kastriot Rexhepi and its statements on Temporality, to Spanish artist Santiago Sierra’s 300 People which consists of a roll-call of past and present rulers and the royal of the world (whose alphabetical selection and placing is itself a statement on how power passes inconsistently across titles and nation states), onto discussions between New York based artist Gregory Sholette and Harvard Professor of Design Krzysztof Wodiczko, to Leger and radical art collective, the Critical Art Ensemble, German Author Alexsander Kluge and his countryman Philosopher and Social Scientist, Oscar Negt, the point is established that there are crucial developments and innovations occurring as there always have been, in what is still seen as elitist intellectual environments. What the Avant-Garde did in the past, through Dada in terms of art activism and Serialism in music, along with elements of postmodernism and experimentalism in literature, and indeed continues to do today, as a form and force in itself, is to show how abstracted or progressive modes of expression defy all catergorisations of background and class, despite being defined or stewarded by those at the far reaches of thought and accomplishment.

They also serve a greater political purpose of course, in defining new means of opposition, with the supposedly ‘chaotic’ voice achieving a new elegance. As poet, playwright and polemicist, Heathcote Williams states, on the birth of Dadaist thought and action, exemplified by Tristan Tzara and his contemporaries but stretching further back;

‘..Apollinaire and co were appalled by the First World War, if indeed they weren’t injured by it. They judged that the military-industrial complexes of France and Germany considered themselves governed by reason. Reason then became the enemy. Through dada and surrealism they declared war on reason. They had a political purpose…’

Leger’s book in the light of this history both details such developments while also finding a new meaning and relevance for the word reason by carefully aligning how effectively the works on offer take that initial oppositional stance and make it one embedded in a new kind of cultural consciousness, that can be appreciated in both the surface, presentational terms of the works produced along with their formative contextual elements.

The feminist aesthetics of the literary critic Helene Cixous, for instance (not included here) are art works or works of literature in themselves, as indeed are the works of Laura Mulvey, from her books on Citizen Kane and Fetishism across the forms, through to her films with Peter Wollen, and in reading the coruscating and revelatory essays, reports, encounters and artworks Leger has gathered together and commissioned, one has the notion of a clear and powerful manifesto taking shape, one that is not only able to reflect the times in which it is written, but also able to offer or point towards effective solutions.

New York based conceptual artist and philosopher Adrian Piper’s opening essay on the limitations of postmodernism and its anti-originality thesis in the face of what the Avant-Garde sets out to accomplish, allows us to enter into and engage with this collection on a high academic level while making perfect sense for the lay-person. As she states;

‘the promotional fervour with which the concept of originality in invoked to market and canonize modern art finds its parallel in the fervour with which the anti-originality thesis itself was marketed as original..’

You’ll excuse the contradiction, but the conundrum is clear. In an unravelling society that is in danger of losing hold of its invented theories both culturally and politically, we are in danger of not only losing the ability to recognise what is valuable and what isn’t, but also the willingness to mourn or even recognise what that loss can be and the effect it can have on us. It is only when we move beyond standard forms that we can find greater access. It is for this reason that abstract expressionism has never truly gone away, as it can be evidenced today in a young child’s unwitting, early scrawl as much as it is in considered Pollockian archive, or in the mastery and eventual mental deterioration of Willem De Kooning. That the shallow ends of current conceptualist thinking and practise in modern art have replaced the true or deeply affecting expressive motions and ideas of the recent past with surface comments on commercialism or sexual identity (yawn), shows how we are in real danger of becoming separated on a biological and spiritual level from the lizard in the brain who teaches us all how to change.

The iconoclastic actor, writer, director and theatrical conceptualist, Ken Campbell once remarked that he had;

‘given up reading regular fiction as it was just about people coming in and out of rooms and falling in love..nowadays I just read science fiction, as that is about everything else!’

That wondrous statement was in fact pointing the way towards a greater glory and landscape for our artistic and critical perception. This isn’t one necessarily defined by a genre such as Sci-fi, or by the scale we might find in the larger classical houses of New York, London or Bayreuth, but the notion of an ‘Opera of the mind’ working with the full orchestra of responses and motivations is an enticing one, purported in Piper’s own work and essay, as it seeks definitions between the postmodern and Avant-Gardism, showing how that very impulse can innovate within the bounds of free market capitalism by commenting on the irrational inequalities that comprise it in a totally explosive way. The connections between free market expression and free market consumption can be joined through the seeming irrationalism of the Avant-Garde statement and in that way, contain an acceptable code for societal understanding.

Noted Performance Artist Andrea Fraser essays the practices of ‘Institutional Critique’ as exemplified by the work of Daniel Buren, Hans Haacke and Peter Burger, focusing on the means with which progressive artworks and the theories that created them in the museum, gallery, symposium and lecture hall, demonstrate how the institutions that ‘impose their (own) frame on art’ are in danger of ossifying both the art itself and the customs of understanding and delivery around it. Fraser focuses also on artists like Michael Asher who

‘took Duchamp one step further..by showing that art can only truly be defined by the discourses and practices and evaluations around it.’

A statement that somehow captures what Avant-Gardism itself accomplishes, by proclaiming that art exists beyond its own creators’ statement of authority. For art and the institutions that showcase it to survive, we need one system of interpretation, one state of being, unified in a communal response to that which is created, one which rises beyond a sense of ownership that otherwise falls into areas of adapting to a given market. It requires its own autonomy and lives beyond and behind its own shadow.

David Tomas investigates Post Avant-Garde practises through a lecture on Kafka’s A Report to the Academy by visuals akin to a kind of graphic score, along with a study of The Southern California Consortium of Art Schools symposium and the editorial work of Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. This comprehensive essay seeks to advance the positions and arguments of Andrea Fraser’s previous one while offering its own advances and here, Leger shows true skill as an editor. This book is not just a gathering of voices and reflections of what is possible; it is a moving and reflex driven process, the literal equivalent of live intellectual engagement or questioning lecture. By attending to the form of the book you are invited into the process necessary to the development of a free- flowing movement of discourse. There is a dance of ideas while at the same time, brain food has been placed in your hand.

In this essay and in this book as a whole;

…art, cybernetics, semiotics, structuralism, psychoanalysis, anthropology, film studies, gender studies, postcolonial and visual studies, as well as trans-disciplinary politics of representation along with the multiple and contradictory composition of social identities…

are the tools chosen to fight and carve a critical future. That the contributors are artists, writers, philosophers, professors of global repute does not limit our reaction to the positions on offer. The book is scholarly but also expansive. It has has a plethora of fascinating black and white illustrations that add to the greater metaphor of understanding and does that rare thing in academia, chiefly enabling the book to stand on its own right and to become an educational course on its own terms. One can become an expert on these theories, practitioners and bodies of work by reading it, regaling others with the knowledge on offer through the intricate pollinations of theory and history. We live in a time of the death of the expert in commercial terms and so as the voices of resistance and disobedience attempt to corral themselves against the prevailing new world order, the fresh ‘daemon at our shoulder’ is no longer a malevolent figure, but one who is able to prompt us into darker action in unenlightened times. For the first time the anger of revolt can collaborate with the aims of the angel whose wings too show a trace of shadow through the white. The previously unaccepted can now be the new language and voice of retaliation. The idea of the Avant–Garde and the worlds it leads to and attempts to suggest and create is the point. That is the true issue. The works on display, once considered cannot be allowed to ossify, just because they have been demonstrated. The painting gathers dust in the gallery as the book does on the shelf, or even the iPad on the arm of the chair. The play has been performed. The music listened to. Now we must rise up and re-engage with what is on offer and allow the buds of our own wings to bolster forth and break the skin. The wounds we reveal will not be easy to recover from but they will at least show the struggle we have undergone in order to contain the things that confront us and which often defy easy representation.

That these thoughts only take me to page 29 of a 285 page volume shows the riches on offer, from Hal Foster’s report on Robert Gober’s post 9/11 installation in which visitors were ushered into a gallery of ‘forlorn objects’ relating the aftermath of that crisis as if they ‘were being ushered into a dream’, to Mulvey’s expert celebration of her colleague Mary Kelly, through to Cosey Fanni Tutti’s end papers suggestion and refutation of what Avant-Gardism can achieve, worlds of resistance are engendered. Sara Marcus’ call for a ‘girl Avant-Garde,’ independent of the totemism of Duchamp’s male urinal re-orders our response and attention, as does the great Chris Cutler’s (Composer, Music Theorist, Lecturer and founding Percussionist of Avant-Garde musical activists, Henry Cow) ‘Thoughts on Music and the Avant–Garde: Considerations on a term and Its public use,’ in which art and the Avant-Garde notions of anti-art, continuity and discontinuity and the very history of artistic resistance in music, is shown as a noble task. As Cutler states when comparing Duchamp’s work Fountain with Cage’s 4’33”;

‘..that (it) in its very quiet way represents nothing less than an attempt to dissolve the category of music. It (in fact) asks of music, as the readymade asks of art: if this is music, then what is not?’

What Cutler calls ‘the ghost at every feast thereafter’ both defines the problematic nature of what the Avant-Garde’s response to society is in terms of being a communal or individual series of statements, along with the subsequent issues of how it is perceived by those living happily outside it. He also points towards a solution. Music as the truest, potentially democratic resource can show us how there are other levels of interpretation and being that can assist the common adventure and help to progress us all towards some form of revelation. We have simply to open our minds and accept this new language, borne on music’s own currents and linguistic status. As Cutler states, Cage’s work after 1951’s Sixteen Dances was an attempt to remove intentionality from the production of all works. To return in fact, to the instinctive response no matter how informed and to create a world of works that lead to communal perception through a notion of what anti-art can actually mean and achieve. This notion helps to return us to the earlier considerations of Institutional Critique that can exist within our own heads and personal galleries of action. Musicians of Cutler’s stamp, along with his colleagues in Henry Coww; Fred Frith, Lol Coxhill and Lindsay Cooper constantly sought new definitions, even if those definitions led to fatalism. When Cutler states at the end of his majestic essay that,

‘.. the avant garde is dead. That is its triumph. Let it lie.’

He is of course opening up new avenues of debate. If the previous forms of resistance are only fit for the archive what new form will our present and future positions take? Will we in the light of the current situation create or forge a new conventionality in reaction to the irrationalism of Trump, Brexit and the dangers inherent in the end of American superpower, or are we condemned to forever remain throwing pebbles, glass and stones against ever more re-inforced steel? The Idea of the Avant-Garde and what it means today is eerily prescient in its documentation of former innovations and current practises. Its relevance is therefore undeniable. This collection shows that amidst the darknesses that surround us there is another colour forming. Whether this is revelatory in terms of pitch or consistency, or simply a matter of a developing tone or shade, we cannot say. But what we can do by examining the examples of works and approaches gathered here – that date back to the early twentieth century and move towards tomorrow – is realise that the idea of and behind such an approach forms the true value and creates the lasting glory, as opposed to the works that assisted its definition. At this time and on this day, nothing as we understand it, works. We must regroup as we disassemble. A once rear (garde) action is fighting its way to the front.

We salute Marc James Leger and the distinguished contributors of this volume. A new light is shining. We just need to know where to look.

David Erdos 11/2/17

Darkly illuminating all that is possible. Excellent work.

Comment by Cy Lester on 16 February, 2017 at 9:36 pmThank you Cy. Best D

Comment by David Erdos on 18 February, 2017 at 11:21 am