Véronique Lane, The French Genealogy of the Beat Generation, Bloomsbury, 2017, 264pp (Pbk published 2019, £25)

Literary scholars have long known that key Beat figures, including Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs, read and admired French Modernist authors. But these cultural influences are often portrayed as superficial in nature, and marginal to the work of the Beat writers. Indeed many critical analyses of these three authors present them as quintessentially American. Véronique Lane’s detailed study challenges such over-simplified accounts. Through close textual analysis of the novels, poems, journals and letters of the three core Beat writers, Lane demonstrates just how much these authors took from French literature.

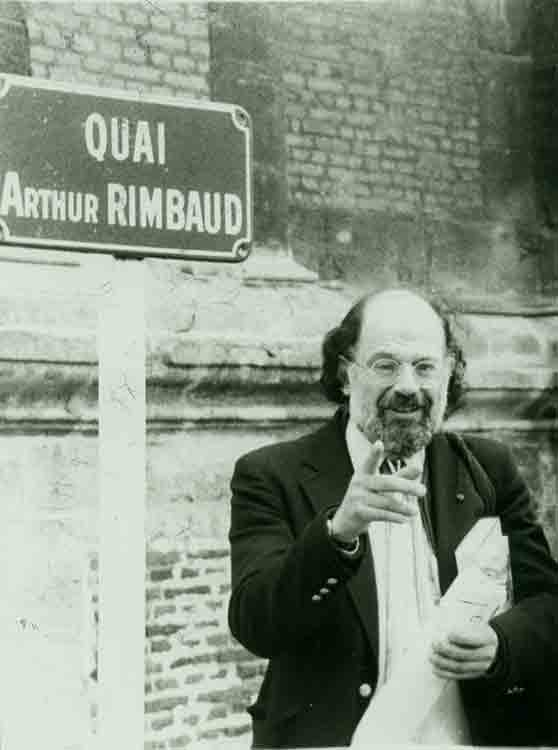

The patterns of influence vary from author to author. Historically, Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’ has been interpreted by critics predominantly in terms of personal biography and period context. But, as Lane shows, in the variorum edition of the poem published in 1986, Ginsberg invites a more complex reading of the text by exposing its literary genealogy, something which scholars seem to have largely overlooked. Lane’s analysis demonstrates that Apollinaire, Artaud, and St-John Perse were all important sources for ‘Howl’. She says: ‘Ginsberg constructed the genealogy of his poetics through a threefold strategy of quotation, translation and encryption, and once this complex strategy is understood, it becomes clear that it was largely through his engagement with French literature that Ginsberg developed the very aesthetic and hermeneutic method of his poetry.’ Ginsberg’s ideal reader, Lane suggests, would have been someone who recognised the hidden quotations and inter-textual references in the work.

Both Kerouac and Burroughs, Lane argues, owed a large debt to Céline, though they responded to his work in very different ways. Burroughs relished Céline’s cynical humour, while Kerouac was drawn to the incidents of compassion in the French author’s work. ‘For Burroughs,’ Lane writes, ‘it is the unchecked violence of Céline’s satire that models a shattering of the novel’s traditional humanism, leading him towards an aesthetic of fragmentation and excess to match his posthuman ethics.’ Burroughs saw strong parallels between the critical reception of Céline’s work and his own, commentators often failing to see the humour in both.

Céline’s importance for both Kerouac and Burroughs, however, goes well beyond matters of personal philosophy. Lane shows how the form and structure of Céline’s first novel, Voyage to the End of Night, is central to the organisation of Kerouac’s On the Road. She traces the roots of this influence in Kerouac’s early work I Wish I Were You, a re-writing of a collaborative novel he co-authored with Burroughs in 1945 called And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks. French cinema was also an important influence on Kerouac in his rewriting of Hippos, especially Marcel Carné’s Le Quai des Brumes (Port of Shadows).

Lane argues that, while Hippos exhibits a degree of ‘name dropping and bohemianism…reflecting the superficial fascination that drew the Beat circle together around the rebellious postures taken by French authors…Kerouac’s rewriting of it begins to critique and go beyond the lure of biography and sociology, shifting towards a direct involvement with the French texts and films themselves.’

Rimbaud was another writer of great interest to both Kerouac and Burroughs. Lane’s examination of Burroughs’ cut-ups of Rimbaud’s poetry in Minutes to Go show that he cut from both the French and the translated texts, doing so with considerable care. Burroughs cut-up poems were not simply a random reassembly of fragments of Rimbaud, but carefully composed texts.

Lane goes on to explore the significance of Gide and Cocteau in Burroughs’ unfinished second novel Queer which he wrote in Mexico the year after he had accidentally killed his wife Joan Vollmer (the book was not published until 1985). Gide’s novel of sexual discovery L’Immoraliste, and Cocteau’s film Orphée, had a particular significance for Burroughs. In Gide’s novel, the main character’s awakening to his homosexual desires contributes to his wife’s death. In Cocteau’s film, Orphée sacrifices Euridice twice, once to his poetry and a second time because he is in love with the beautiful figure of Death. Reference to Joan’s death is absent from Queer, yet it cast a ghostly shadow over the text. To quote Lane: ‘Gide and Cocteau mediated for Burroughs a deeply problematic relation of life to literature, in which the issue of where his writing belonged, its genealogy, was emotionally charged by the question of what did and didn’t belong in it.’

A further chapter investigates Burroughs complex relationship, and rivalry, with Genet’s writing, and the book’s final chapter explores parallels between Burroughs’ Mugwups (from Naked Lunch) and Michaux’s Meidosems.

That it has taken so long for a scholarly study to elaborate these cross-cultural connections in the highly persuasive way that Lane does, is perhaps because of the barriers of language. Few Beat scholars have been sufficiently versed in the two literatures to see the links. This is both a scholarly and an immensely readable book.

© Simon Collings 2019

[…] just published a review of The French Genealogy of the Beat Generation by Véronique Lane in International Times. This […]

Pingback by The Beat generation’s French roots | Simon Collings on 27 October, 2019 at 1:38 pm