October Gallery, London, December 9th 2016

A proper theatre is formed of ideas. Whether under the glare of old suns primed as they were by Greek judgement or by the uncomprehending eyes of the present, the theatre should challenge and in an indirect way try to teach. This seminal play, written by Heathcote Williams after conversations with David Solomon and Mike Lesser and informed by notions popularised by Robert Anton Wilson, is one of the richest of his dramatic works and one that certainly struck me as a teenager, pushing at the doors of literature and seeking entrance to the mysterious world of counter cultural viewpoint, whilst easing my way past the sharp weapons of the old avant garde.

The play takes the form of a television interview with a man who claims to be 278 years old, a little too young for Shakespeare but certainly old enough to have lived through the days of Courbet and the Paris Commune. Frazer’s golden bough was something within easy reach of this individual, and as he drops names and experiences across the intervening time period, one becomes aware that this play in particular is a roller coaster ride not just through theories of extended mortality, but through the history of rebellion itself.

In his summary of the issues and aspects that have affected his existance 278’s justifications and deliberate obfuscations abound. They are there to both entrance and bewilder, herding the audience into a fresh new perspective where the fields of perception place them as the cattle, steeped – as all cattle are – in bullshit.

The bravura nature of the flow of ideas and argument needs a rapid delivery, a semi-frantic yet nevertheless coruscating rim-shot striking journey from word to word-image and then back again towards word. In the production mounted on Friday, December the 9th 2016 at the remarkable enclave of artistry, the October Gallery in Holborn, the approach was more stately than revolutionary. Jack Moylett, whose touching enthusiasm for the play has led to this production here and previously in Berlin performs 278 as a wise old cove warmed by a low fire. He seeks to mystify and seduce, perhaps aiming for the confident otherworldly twinkle of Patrick Troughtons’s Doctor Who, embellished with a dash of William Hartnell’s austere stroppery, and his portrayal has a pleasing composure to it. It does not however, quite capture the strangeness of atmosphere if not content in Williams’ dramatic work, the very element that led to the mystique he was often awarded. Williams’ career has been a healthy mix of strident polemicism and poetic entrenchment. He was, is and will remain the ultimate cult artist, and it is important to honour the eerie glow of his work, as much as you value its contemporary relevance.

The Immortalist is not a play in the conventional sense (but neither are Harold Pinter’s, Samuel Beckett’s, Caryl Churchill’s, or Jim Cartwright’s for that matter), it is a theatre essay, rippling with successive waves of discourse, conjecture and japery. It crackles with the singe of ideas, from the notion of sublimating your own shit in order to distill immortality’s crucial ingredient, Indole, to the idea that death is a lifestyle choice, a fashion statement of the deadly, keen to keep hold on us all.

The psychedelic exuberance of his 1970 masterpiece AC/DC, is the begetter of this play. If you like, it is The Immortalist’s , wild older brother, who has defied the conventions of upbringing and expectation and gone out into the world to fuck and be fucked in its myriad corners, before wiping himself clean on the shattered souls of the lost. This play therefore becomes the studious and refined younger brother of the former, who has learnt from the wayward nature of his sibling, and started to reflect on his exploits with several bright opinions at hand. It is a fast and difficult music but one which soon has us singing as the vitality of Williams’ language begs for celebration, and Williams as word magus directs us all through the roar of his song. The best plays aspire to musical levels of delivery and resonance and must be served accordingly. Moylett’s easy irish charm captures some of this music but also misses aspects of it’s strength. Pacing and levels of interpretation could be more closely followed, but placed in their stead, is a delicate sharing, a lulling which certainly embodies the sensualist aspect of Heathcote Williams’ life and work, while foregoing much of the aforementioned stridency.

What is wanted on stage is an echo or embodiment of what one receives on reading, a shadowing of Heathcote’s laughter, as he whips up and conjures a range of responses that allow us to dance towards death. This vital brew requires the mastery of a conductor with his eye on the prize and a racing driver with his grasp of the clutch, as he veers towards it. We must, over the course of fifty minutes crash through the windscreen of experience in order to renegotiate our place at the wheel. What must be rammed in our faces should be a new weather, designed for the fresh hole before us, igniting the throat and the mind. A signpost subsumed by the road.

The direction of this play is at times, static. 278 and the Interviewer played by an exquisitely voiced Allison Mullin, either sit or stand without further staging and this relative immobility stops us connecting fully with the events described in the text and the emerging situation between the two characters, something that should be shared with us, placing us there as they talk. As the Interviewer comes to understand, sympathise and disagree with the points on offer, she too has a chance to begin a journey, evident in her struggle to grapple with the notions at hand. ‘Time is a false alarm…’ ‘Analyse. Transcend.’ ‘..stimulate a different chemical mandala in your body..’ ‘..disobey the alien order..’ Again and again she is given the keys to the chamber. Again and again she refuses to move.

A much sought for conclusion of the play is for 278 and the Interviewer to somehow dematerialise, or transcend in some way, but of course that is not truly the point. It’s possible that the figure of 278 could be played by an animated skeleton or yoda like, mummified puppet voiced by an actor, or imagined as a combination of darkness, wisdom and devilry, as if Harold Pinter in all of his black eyed glory had fused with the type of acid casualty glimpsed in the party scene of Midnight Cowboy, before being glossed by Machen’s Great God Pan. 278 is a self defined god primarily through his defiance. And his rejection of reality as we understand it is what lifts this conversation into a new realm of impact, in which the exchanging of states and extremes of being is the ultimate goal.

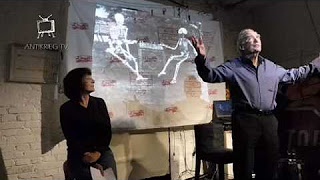

As he is gently interrogated we are encouraged to undergo the various stages of belief, from scepticism to adoration and there is much in this performance that allows that. It does however need tightening. The basic setting of two chairs in front of a hung backdrop featuring a blow-up of the playscript’s original cover (of two skeletons in conversation), is used, but was off kilter and compared to the shuffling informal opening did not help establish the appropriate context and atmosphere. The television setting is not important as the piece is at heart a conversation in the truest extent of the word; and no doubt some would argue that my concern also isn’t, but when one is presenting ideas and images of this calibre, a level of precision enhances both the understanding of what is shown and more importantly of what is implied afterwards. It could be argued that the last thing theatre needs is elaborate decorative elements of setting. We must instead fill the space with words and their tokenistic magic, especially if they stem from linguistic trickster’s of the stamp of Heathcote Williams. Having said that of course, it should be noted that Williams is very much his own postal service in terms of poetic achievement, so that is a task in itself.

What I wanted therefore was a greater sense of involvement and control. There were some affecting moments of commitment when Moylett raged but perhaps in this one off performance at least, a little too much gentility. Theatre should beguile us as effectively as it transports and affronts us but I wanted the delivery to lay waste to the doors truth breaks down.

I am not of the mind that message trumps nuance – and indeed the low animal bearing that name makes an appearance in the text, albeit in a slightly heavy handed way – but I am of one that the passing on of full creative and critical understanding is the point of each performance between actors and audience. The best plays achieve this and we must not stand (or sit) in their way. But we must allow for the physical nature of the language to manifest itself in terms of both thought and action and there were at times here, a little too much restraint on display.

All theatre is hard work but the real energy, the true energy is hard to capture and one that many actors shy away from. The delivery of a playtext is not set in stone. It is afterall, written to take place in the air and the air is forever changeable. The essential truth is the same (we must for instance, continue to keep breathing) but the approaches can vary if the idea is to live. It is vital in this play that the audience believe they are sitting in the same room as someone who has moved through and past the ‘black kingdom’ and begun to reclaim higher forms.

278’s ingenious history of the twentieth century’s flirtations with genocide from the ‘14-18 folk festival’ to ‘the 39-45’ one, leaves us with a view on the flippancy of man’s actions. It takes us through the ethereal nature of Timothy Leary or Krishnamurti type thought via the uses and abuses of Tri- and Di-methyl Tryptamine and a ‘messiah like universe’ of stopped clocks. Its final statement is one that changed my personal view of what was possible with writing; chiefly how to make the most causal statement the most revelatory. When it arrives here it is highlighted a little too heavily – even by something as simple as a head turn – when it should perhaps take us by surprise and leave us at the door of conversion, but the flavour is still fit to taste:

‘There are people alive now who are not going to die. Put that on the news.’

If not the fact in itself, then the fiction is useful. In fact, more than useful, it, as a statement, totally transforms who we are and how we understand things to be. In nineteen syllables, Heathcote Williams provides a near textbook haiku of transcendence. It is a line and sequence of thought that demands its own theatre and virtually its own medium. And for me ranks with that other great and fundamental statement of importance, found in Petey’s final appeal to Stanley Webber ‘The Birthday Party,’

‘Stanley, don’t let them tell you what to do!’

These are commands and acts of word-magic aimed at the strength in us all.

If this production had been played as a recital in the round a deeper sense of sharing would perhaps have been received – though it should be noted that it was received by an audience greatful to hear the play again and to delight in the majesty of language on offer – and this would perhaps have suited the style of Moylett and Mullins’ delivery more effectively. By moving slightly away from what I hesitate to call ‘certain rules of presentation,’ some elements slipped past us. The effect was of missing certain choice pieces of meat – which 278 eats ‘if it meets him’ – in an ever deepening stew, and yet everyone present was aware that amidst peas and chicken there was dazzle and duck still to come.

The word concert remained and ultimately moved like music. As we must move from disaster towards some sort of revolve for the soul. Wandering Albatross landed well and showed refined dedication. From the heights of grand theory to the oceans at play within us. The truth must be sent by albatross, eagle, pigeon. The governing air’s in the writing. If we relearn how to breathe it, we may also relearn how to live. In this play tonight we caught a glimpse of the process. The ideas achieve flight even if their origins remain earthbound. Humour and gall elevate them as the divine is revealed in bullshit. As the stunned cattle gaze towards the storms of transference, we hear the grand oxfordian chuckle as he fountain pens and exhorts us:

‘Dead men of the world unite. You have nothing to lose but your lids.’

David Erdos 10/12/16