.

.

.

American record producer Joe Boyd has had reason to invoke a law of unintended consequences, which has been a theme throughout his career. His first experience was back in 1970 when he made an unassuming album with singer-songwriter Vashti Bunyan, called Just Another Diamond Day. There was no stampede of pre-publicity to announce it or furious competition to release it. And on release, Boyd estimates it sold 200 copies.

From those 200 buyers, however, word spread of how good the songs on the album were: charming, domestic, and sweetly sung. People became curious – with so few copies in circulation, the scarcity bred collectability, and the album became a valuable artefact. When it was finally released again, this time on a more widely circulated compact disc, it fared rather better.

“It’s now sold around 150,000,” Boyd told me a few years ago. Albeit by an oblique and unintended route, it had finally become a success.

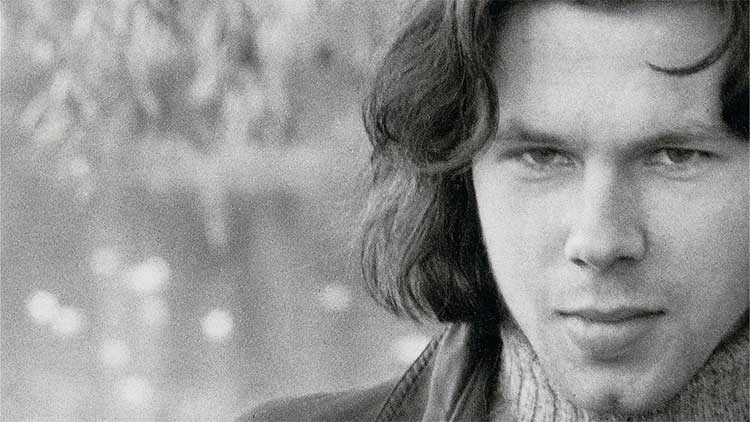

At about the same time he was recording with Vashti, Boyd was also struggling to find an audience for another artist, the English singer-songwriter Nick Drake. Drake was a large but unassuming talent, bringing a crisp and elegant sensibility to a folk guitar idiom then exemplified by nonchalance. Helpfully, he was also young and good-looking.

Drake was shy, but determined. He had busked in Europe (apparently once playing in a café for members of the vacationing Rolling Stones). He had performed at a May Ball in Cambridge (where he was a student at the university) and been discovered at London’s hippy stronghold the Roundhouse by a member of the band Fairport Convention. His debut album Five Leaves Left set his pastoral compositions in exquisite and well-judged string arrangements by Robert Kirby, (a friend from Cambridge). However, with its maker ill-disposed to the rowdy environment of the British folk clubs, he was without a forum to win more listeners.

.

Another album, Bryter Layter, followed – this time backing Drake with a drummer and electric instruments. It was more widely noticed, but made no more commercial waves. By the time his third and final album, Pink Moon, dropped Drake’s thwarted commercial ambition and struggle with mental illness had manifested themselves in starker compositions.

.

His final five songs (released officially years later) are magnificent, but not for the faint-hearted. Drake died, apparently by his own hand, in 1974, at the age of 27.

Like a joke in rather poor taste, with Drake’s death began the unintended consequence of his rediscovery. Effectively unknown in his lifetime, nearly 45 years later we’re at a point where magazine covers celebrate what would have been his 70th birthday this year.

There are handsome Nick Drake books and documentaries (Brad Pitt, a fan, has narrated one). There are tribute concerts, and an audience hungry for the snippets of additional music and data on the margins of the Drake canon. The three Drake records, which remained in print at Boyd’s insistence, have now sold many copies, in many repressings.

When the first flickerings of revived interest came to light in the late 1970s, things were not easy for the Drake consumer. There were the records, but beyond that, devotees could only do what disciples have historically always done: make pilgrimages to important sites. Several years after Nick’s death, his parents Rodney and Molly began receiving unexpected callers at their home at Tanworth-in-Arden in rural Warwickshire in the British Midlands.

Rodney, a former civil engineer, was a gadget enthusiast who recorded family moments on reel-to-reel tapes. Now, to those curious enough to visit him at home, he gifted them unheard home recordings by the young Nick Drake. The legend of Drake as some kind of doomed romantic hero diminishes his talent, his ambition and his struggle with mental health – but something in the story of a major musician who died before his time inspired a growing number of people to investigate.

Rodney’s tapes gradually made their way from the hands of enthusiasts, into the wider bootleg market for rare recordings. Finally, in 2007, they became an official Nick Drake release called Family Tree. This included Nick’s performances – cover versions of songs by Bob Dylan, Jackson C Frank and Robin Frederick, a woman with whom Nick had busked in France. There was a Mozart piece played by a family group, and two songs written and played by Molly.

The songs by Molly Drake included on Family Tree – Poor Mum and Do You Ever Remember? – were written in the 1950s, during Molly’s afternoons alone in the house. These are private recordings (so private Rodney would apparently set up the equipment, but not operate it) and they reveal Molly as a thoughtful composer. The songs are formal, with a gentrified poise, but are also personal musings on fleeting moments – all the more powerful for having themselves been caught.

.

The two songs on Family Tree led to an album, Molly Drake, being compiled in 2013 (Molly died in 1993) and now to a new and definitive two CD/book set. This (as does a compilation of Robert Kirby arrangements for Nick Drake and others) now arrives in time for the 70th anniversary of Nick Drake’s birth and packages the Molly Drake recordings with seven additional songs, poems, song lyrics and family photos.

Nick’s songs quest for a certain freedom, their subjects seeking to evade time and responsibility. Molly’s are more wistful, perhaps more resigned to being caught. For every path taken there is one unexplored, and her compositions often contemplate what might have been. A song called Happiness pictures contentment as a startled bird: “Try and grab at it and woe betide you/I know because I’ve tried …”

Boyd heard Molly’s music in the early 1980s. “I was stunned,” he told me when we spoke. “She had always been so dismissive of her ‘hobby’ songwriting that I had no expectations of the quality I heard. I was astonished to hear so many pre-echoes of Nick’s songwriting.”

He has called it the “missing link” in the Nick Drake story. Robin Frederick, now a musicologist, agrees. “Unconsciously, I think he had embedded the tenderness, the vulnerability, and even chord progressions of Molly’s songs from his early years at home,” she says. “Her music is there underneath.”

It’s ironic that Nick, who wanted to sell records, found it hard to do so, while Molly, who didn’t even imagine a public forum for her music now has an attentive one. Possibly it’s why the voice recorded here has a freshness as well as a family resemblance. Although recorded in a comfortable home, these songs have not been domesticated, instead arriving essentially unmediated, a bolt from the blue.

Twenty years before this medium became a popular public form of expression and before its practitioners had the name, Molly Drake was a singer-songwriter, putting her feelings to music in an accomplished and melodic way. If her work calls anyone to mind, though, it’s no one so much as Vivian Maier. Unknown in her lifetime, Maier worked as a nanny in Chicago, but was discovered on her death in 2009 (when her archive of negatives was discovered) to have been a street photographer of major stature. Molly’s work doesn’t quite have the scale or social consequence of Maier’s but it does pose questions about the nature of private creativity. Who, in the absence of an audience, were these songs for?

Whoever it is, the songs have waited patiently for their small moment, and offer some rewards for the curious. One might do worse to behave as Molly and Rodney did themselves – open the door and treat them kindly.

John Robinson

https://www.thenational.ae/