The famously prolific poet Jeremy Reed once claimed that you could pave London with the books he’s written. It’s a disarming thought. For a long time now a devoted readership has been walking those Reed-paved streets, illustrated, laminated, titled: Patron Saint of Eyeliner, This is How You Disappear, Piccadilly Bongo etc. One of the capital’s outstanding poets, he is a London specialist. Though his imagination can travel north, south, east and west, he is most often to be found in central London, as the opening section of his latest book attests, called ‘Central’. It would be fair to describe him as the poet laureate of Soho, an outre-bohemian successor to the legends of past history and living memory who have always populated the zone.

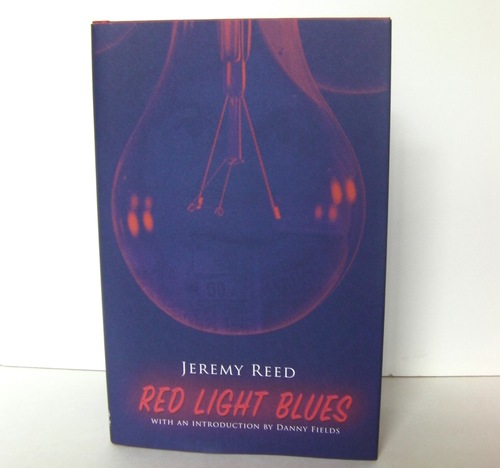

Red Light Blues is a true Soho book in that its subject matter is Soho, it was written in the cafes of Soho, and is published in Soho by bookshop-cum-cocktail bar The Society Club. It’s a fine production. The title, and its jacket image, evoke the melancholy of the red light district, where bulbs magnetise punters, but where sensitive souls identify with a sexual underclass, not just the models of the stairwells but the rent boys of more subterranean demesnes. The first poem ‘Meeting with Francis Bacon’ is awash with male prostitutes, atmospheric rain and exotic alcohols. The great painter is there like a debauched Virgil guiding the younger poet through the circles of a neon inferno. This is not realism, but something concentrated, somewhere between baroque and expressionist.

The second poem, ‘Looking for Blake’, follows the trail of an earlier Soho genius. Broadwick Street, Poland Street and Dufour Place are namechecked but the author of ‘The Tyger’ is nowhere to be seen. Some of his former sites are now occupied by manicurists, beauticians and hairdressers. The closing line makes a sardonic comment on never-ending gentrification of our time: “I know a Blake but he does real estate”.

Reed introduces more of his dramatis personae. ‘My Familiar Junky’ tells the story of the poet’s encounters with a heroin addict who regularly asks him for spare change. The character is given her own dialogue, mostly about the male poet’s cosmetics: “you’re wearing make-up ain’t you luv”. The cleverness of the poem is in its suggestive depiction of “our routine” – (note the Burroughsian word ‘routine’ and the Burroughsian spelling of ‘junky’). The reader intuits that the same exchange of conversation, the same exchange of money will happen again in the Soho streets – Manette Street with its charity for fallen women – as well as in the streets of the poem. Reed creates an eternal present, an eternal moment. The poem is also notable for its two-way pathos. The reader feels for the poet even as the poet feels for his fellow outsider:

I dig into crumpled jeans

to help facilitate a wrap

mainlined into collapsed veins

and give too much of too little

as part of our complicity,

a street exchange ‘your make-up luv

it really suits you honey’

The figure of the poet here attains a state of grace which his beloved Hart Crane calls ‘Chaplinesque’. Each new character adds to the Soho tableau. Reed has by now mastered the art of writing books which are books rather than poetry collections. The vignettes become sequences, the sequences become a human pilgrimage, albeit an unholy one. ‘Bad Living’ sketches the poet reliving certain bad memories – enigmatically presented – but concludes with a walk through Leicester Square in the company of a recurring, very drunk, Francis Bacon.

Words, as well as characters, recur: ‘launder’, ‘lick’, ‘LED’. One word I noticed a lot and which sums up the testament is ‘euphoria’.

Reed’s ‘Chinatown’ section recalls a single poem from John Wieners’s The Hotel Wentley Poems, ‘A poem for vipers’, a self-portrait as literary outlaw eating noodles in a San Francisco Chinese restaurant, with a drug dealer called Jimmy:

I sit in Lees. At 11:40 PM with

Jimmy the pusher. He teaches me

Ju Ju. Hot on the table before us

shrimp foo yong, rice and mushroom

chow yuke. Up the street under the wheels

of a strange car is his stash—The ritual.

This might be a conscious or unconscious starting-point for Reed’s sequence-within-a-sequence, a unique celebration of an important but overlooked Chinatown, Soho, London (which I last read about in Paul Kingsnorth’s Real England).

Dim sum, gingery pancakes, jasmine tea,

a mobile Beijing, like I get the lot,

illicit dealing, drugs, cheap cigarettes

right on the moment happening in the court,

choked up illusory shimmering air,

take it or leave it I mix with my sort.

The final line is a masterclass in linesmanship, ten words, ten monosyllables, trochaic pentameter on paper, but which would sound four beats orally. It’s also a plangent personal statement, inviting the reader to take sides.

Whether you’re with or against him, he’s relentless. Another section “My Gang’ homages friends and fellow foot-soldiers of bohemia. ‘Meeting Jake Arnott’ snapshots a moment “at Old Compton Street’s Patisserie Valerie” and is a warmly affectionate and affecting tribute. Reed’s praise-singing is primal, utterly eccentric and endearing, finding new ways to praise new phenomena.

The ‘Some Kinda Love’ section takes its cue from Lou Reed’s arch song of the same name. Reed is as profoundly immersed in the work and world of Lou Reed as he is of William Blake. Having written Waiting for the Man, the biography of Lou Reed its subject most appreciated, Jeremy Reed has learnt much and taken much from that exemplary artist, the most literary of rock stars. As Lou Reed claimed to have invented the character Lou Reed, so Jeremy Reed has invented Jeremy Reed. A poet who can be as impersonal as anyone is, in these pages, more intimate than ever. ‘Some Kinda Love’ signposts Soho as the epicentre of sexual transgression in London and boldly portrays himself among his fellow transgressives.

If the charming introduction to Red Light Blues by ex-Ramones manger Danny Fields establishes a music world connection, the final section ‘Soho Out’ ups the ante by presenting a sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll poet. The poem ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Poet’ is a poemanifesto on the theme. Its message is irrefutable. Reed is surely one of the most charismatic and abandoned presences in contemporary English poetry. He has learnt from everyone. An earlier book contained a suite of elegies for Derek Jarman, mentor of the feral in art. The poem ‘Soho Out’ looks at the city through the eyes of valium withdrawal, with a nod to another ex-denizen of Soho, Sebastian Horsley. Reed is wise enough to also ingest liquid tons of China tea, which keeps him clean and radiant. Reed is rock ‘n’ roll without the budget, the rider, but a necessary art and artist, showing how it can be done and always was done. This book’s miniatures are – in the words of Blake – “ever-expanding in the bosom of God”. He is saving Soho from the tyranny of the bland.

.

.

.

Niall McDevitt

.

Niall McDevitt

Photo of Jeremy Reed in Marshall Street, Soho, by Max Reeves

.

.

.