“Such a fine, sunny day, and I have to go,” 21-year-old Sophie Scholl lamented, before she was guillotined by the Nazis. “But what does my death matter, if through us thousands of people are awakened and stirred to action?” Scholl was a member of the White Rose, a small, anonymous group of mostly university students who hoped that by distributing leaflets and graffitiing public spaces, they could awaken complacent German intellectuals.

Seven months earlier in June of 1942, Sophie was sitting in a lecture hall at the University of Munich when she noticed a slip of paper under her desk. She picked it up and began to read, “Who among us has any conception of the dimensions of shame that will befall us and our children when one day the veil has fallen from our eyes and the most horrible crimes — crimes that infinitely outdistance every human measure — reach light of day?”

The mass deportation of Jews to concentration camps was now fully underway. As a child, Sophie had been a member of the girl’s branch of the Hitler Youth, but had been troubled when her Jewish friend was prohibited from joining. As Jud Newborn and Annette Dumbach explained in their book, Sophie Scholl and the White Rose, Sophie and her siblings — still under the sway of the Hitler Youth — often clashed with their father, an avowed anti-Nazi. One evening, walking along the Danube, he had turned to his children suddenly and hissed, “All I want is for you to walk straight and free through life, even when it’s hard.” Slowly, skepticism wormed its way in. Her alienation reached fever pitch in high school as nearly everything she learned was steeped in Nazi propaganda. Then her father was arrested when his employer overheard him calling Hitler “the scourge of humanity.” But reading the pamphlet, Sophie was conflicted. She had two brothers at the front, her father was in jail awaiting sentencing, and her mother was ill. Waiting to report anti-Nazi literature was a crime. She walked out of the lecture hall with the pamphlet in hand.

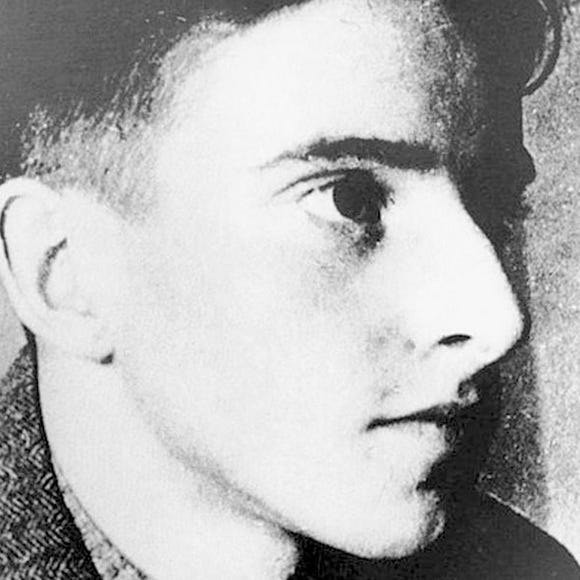

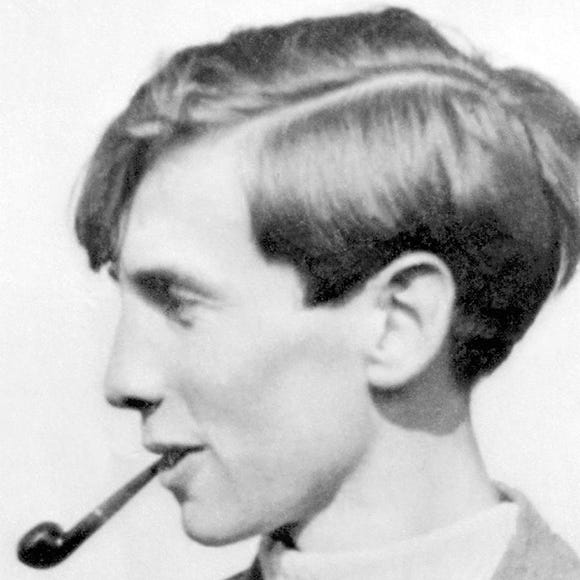

Sophie went in search of her older brother Hans, who was a medical student also at the University of Munich. He wasn’t in his apartment, so she waited for him there. She found a book by the German poet, Friedrich Schiller on his desk and began reading. One page in particular was covered in marks. The exact words she had read in the pamphlet were underlined. Sophie was terrified. Her brother must have had something to do with the pamphlet. When he returned, Sophie confronted him. He demurred. Two of his friends arrived, and eventually they told her the truth. Her brother and four others were a part of an anonymous resistance campaign. Sophie decided to join them.

For the next month, the group worked on their campaign. They bought stamps and paper from different post offices to avoid arousing suspicion. They collected quotes and copied them with a mimeograph. The second pamphlet read, “Since the conquest of Poland 300,000 Jews have been murdered, a crime against human dignity.” The third called for the sabotage of armament plants, newspapers, and public ceremonies, and the awakening of the “lower classes.” Rumors buzzed about the pamphlets. As the language of the pamphlets became increasingly explicit, the gestapo ramped up their efforts to find the perpetrators, arresting anyone at the slightest suspicion of collaboration.

In July, four members of the White Rose including Hans were ordered to spend their summer break working as medics at the Russian front. On their way, they passed the Warsaw ghetto and were horrified. Once in Russia, they understood that Germany was losing to the Soviets despite the fact that the Nazis claimed otherwise. When they returned home in November, they were emboldened, and the White Rose increased the number of pamphlets they were publishing. The group traveled by train to distribute the leaflets all over Germany. They wanted to create the impression that the White Rose was a vast network, that the public was behind them. When the Germans admitted their loss to the Soviets in February of 1943, some White Rose members went out at night and graffitied the words “Freedom,” “Down with Hitler” and “Hitler mass murder” on the city hall and other public places. They believed Nazi Germany might be crumbling, they just needed the people to realize it.

On February 18, Sophie and Hans brought suitcases full of the sixth pamphlet to the University of Munich and left them in classrooms and hallways, and on windowsills. They — some accounts say just Sophie — went to a balcony that overlooked one of the university’s main courtyards. As hoards of students streamed out of class, the pamphlets fluttered down from the sky above them.

The sixth pamphlet was the last. A janitor had seen Sophie and her brother, reported them, and shortly thereafter they were arrested. Sophie was interrogated for seventeen hours. Four days later, when she finally emerged at the “People’s Court” in the Munich Palace of Justice, she had a broken leg. As Kathryn Atwood described in Women Heroes of World War II, the courtroom was a bevvy of Hitler supporters. The judge launched into a tirade about how the members of the White Rose were weakening Germany. The defendants were not given an opportunity to speak. And then, suddenly, a voice called out. It was Sophie. “Somebody had to make a start!” she yelled. “What we said and wrote are what many people are thinking. They just don’t dare say it out loud!”

After she interrupted the judge several more times, Sophie, her brother, and another member of the White Rose were sentenced to death. On the back of her indictment, Sophie scrawled the word “Freedom.” Within hours, the trio were lead to the guillotine. From the executioner’s block, her brother shouted, “Long live freedom!” (In total, roughly 5,000 dissenters would be similarly executed.)

After the execution, a pro-Nazi rally was held at their university, and the janitor who had reported them was given a standing ovation.

“Es lebe die Freiheit!” (Hans Scholl’s last words as he walked to the guillotine.)

“Ich wurde es genau so wieder machen.” (Sophie Scholl’s last words to her Gestapo interrogator.)

Bless them all.

Comment by Heidi Stephenson on 20 September, 2017 at 4:39 pm