The disused frontier post at Col du Pourtalet in April 2011, 25 years after I might have passed.

(Image: Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0)

Chernobyl went up and I only knew by chance. Two or three days had already passed. This was urgent headline news. We weren’t just being rained on, but irradiated – though from a later fallout plot[i], not only was I luckier than most of Europe but better off than if I’d been at home.

How much and yet how little the world has changed since 1986. Not that I’d know the latest news now – not if I was trying to travel. Isn’t real travel about disconnection from the familiar? How much harder it must be nowadays. “No mobiles!” Says Issach de Bankole, the self-possessed hitman in Jim Jarmusch’s The Limits of Control (2009) – and getting rid of mobiles would be the first requirement for real travel.

But perhaps most travellers prefer to arrive? Hence the subsidised disaster of air travel. If we had to pay what flight really costs, only a handful of fat cats – conscience naturally burnt-out – could afford it. A mild form of suspended animation, air travel makes everywhere like everywhere else. Who can be blamed for wanting to arrive? After one or other interchangeable coma, at journey’s end, a thin backscene buckles or shines under a dissimilar humidity: hotter and more exotic; colder and bracing . . . and maybe a hire-car will flatter the tourist they’re a traveller? How can this prescription, the all-too-widely beaten tracks, be escaped or subverted? Only by how we look at the world? Is it possible to get by with open-eyed trust, or failing that, with determination? Can we bear to leave the controlling custody of technological connectivity behind?

Re-watching The Limits of Control recently, there was plenty of time to reflect on such questions. Perhaps the Jarmusch film that gives freest rein for speculative or lateral thinking, The Limits of Control, flirts with the idea of travel but often finds itself in ersatz places of the perfect sort to illustrate the tendency towards homogenisation and the fade from reality. Between bland, tourist voids, occasionally a truer life haunts grubbier graffitied streets or explodes from bizarre architecture. And behind it all, is the vast outback of Spain, the mountains and deserts.

But comfort has become our decadence: the call of fluffy towels and hot showers; the standard coffee bars and restaurants; even the naked femme fatales without a sting! Don’t get me wrong, I love the films of Jim Jarmusch. Although they may have become more contrived over the years, (and The Limits of Control’s, Christmas-Special parade of celebrity friends can become irritating), they always contain nuggets of value. Dead Man was the highpoint: a specific yet metaphorical work of genius. Others edge that high and I’m always hoping he’ll scale that altitude again. Yet when any artform exceeds even the high pass, there’s little question that this is, in some part, due to Providence.

Cutting short my euphoric tendencies I must return to the wastelands, the desert scrub, silent and patiently waiting behind The Limits of Control. For several minutes between Madrid and Seville (41 – 46 mins) this passes outside the train by which the tourists are insulated. On second viewing, I felt more favourable towards such languor. It gave peace rather than frustration. A time to reflect such as the visual and aural bombardments of e.g. Godard, rarely grace. For all his insights, Godard is always likely to leave non-French speakers lagging. Godard’s work is ideally suited to DVD – which allows you to watch and analyse at whatever speed you like, and untangle the over-lapping subtitles.

Unforceful and calm, Jarmusch does not pressurize us with overload. The Limits of Control attains a dreamlike pace well-suited to Rimbaud’s sentinel watchwords – gentler in atmosphere than the images they portend: “As I descended into impassable rivers, I no longer felt guided by the ferrymen.” For the ambling pace and whimsy of The Limits of Control – if you become suitably unruffled – can open your inner space . . . And maybe the subsequent paths your thoughts might take, are more influenced by the film than you are aware of?

- Somewhere in Catalonia, April 1986.

Real travelling too, gives plenty of time to think. Usually in an agonised way. Travelling is rarely a holiday – not in my experience. That first time I crossed Spain by bicycle in April 1986, it was hardly the Spain of Laurie Lee’s Midsummer Morning, yet oxen pulling ploughs were not uncommon. For six or seven weeks over the Pyrenees and across France I remained existentially alone. The physical side of it was unimportant[ii], it was the mental state, the long dark weeks of the soul, during which thunderstorms raked Catalonia and the pass into France was almost blocked with snow . . . In their little glass booth by the lowered stripy barrier, how deadly amused those border guards were by an ancient bike appearing from the drift of light blizzard onto the salt cleared area. That Royal Enfield bicycle was to me a legend, and like many legends it hadn’t long to live – at least not in my sight. Stolen from a bike shed in Exeter 5 months later, padlock chains cut, I never saw it after that. I still hope we might meet again someday. The Exeter police reckoned that when bikes are stolen in bulk, the older ones, renowned for their endurance and solidity, are shipped out to Africa. I suppose a long afterlife in Africa is not a bad fate. At least there, the Royal Enfield would’ve been treated with respect. It probably remains 100% needed.

If Byron published Childe Harold now, or Colin Wilson, The Outsider, I doubt anyone would notice. If ten modern equivalents were published every month, again the result would likely be indifference. They certainly wouldn’t make anyone famous overnight, or if they did, the consequence would end with the fame: surface over meaning, celebrity over depth. Likewise, it seems inevitable that the relevance and power of art will be lost. The Shock of the New[iii] has all been done before and who cares about depth? Reality is Arbitrary, certain speakers in The Limits of Control would have us believe. Also, that life is a handful of dust or dirt, (or radioactive waste). Both might be true of the situation we’re now in. The question is: can we turn it back?

When Bill Murray takes off his toupée and places it on the skull towards the end of The Limits of Control (96.54), the bewigged skull more than suggests Andy Warhol. And as much as this proposition to me sums up “the whimper of Pop Art”, so it also sums up the futility of celebrity, as well as the fear in a handful of dust we are left with. Yet it is also funny. The species of laughter that stops us from crying? The Warhol memento mori may or may not be co-incidence. If I knew Jarmusch, I’d ask him. “Art is what you can get away with.” Warhol reputedly said. Of course, he may have been joking. But I don’t think Jarmusch is teasing us in The Limits of Control. Perhaps he only wants to avoid being embarrassed by his underlying seriousness? Could it be as Philip French suggested in the Guardian[iv], that “we’re watching the revenge of the downtrodden upon globalism and capitalist society”? French’s positive review is quite a contrast to Peter Bradshaw’s[v] – and there’s a lot of truth in both.

Back in 1986, en route to Barcelona on a cheap midnight train, the few passengers unable to afford a couchette were constantly awoken from the stiff, upright seats to which we’d been consigned, by spoilt skiing brats. Banging doors, acting like the world was theirs, these upper-class oiks were interspersed with brusque officials demanding “Billets!” for the umpteenth time. Between officialdom and contempt, sleep was lumpy, nightmarish, impossible. Eventually, it was dawn, and through the vineyards encircling Perpignan, at times the Mediterranean came into sight, looking as weary as I felt. Resigned. Without sparkle. At Cerbere the Enfield was banished to a different train, a goods or parcels “Siguiendo luego” – following later. I wondered if I’d ever see it again.

Missing the coast at Tossa de Mar – principle location of Albert Lewin’s mesmerising 1951 film, Pandora and the Flying Dutchman[vi] – I arrived in a flat state of mind, deprived of my principle companion, disoriented by its loss. Day after day I went to the terminal at Estació de França, and eventually saw my friend in the parcels room: tent and saddlebags loaded on the back; the old dynamo-powered headlight; utterly distinctive. Yet still I could not claim it. Using up vital money stuck in a windowless cupboard in the city, my appalling classical Spanish was worse than useless. I tried to enjoy my unexpected time in tropical gardens and squares, wandering the docks and avenues, inevitably discovering the exceptional Picasso museum, the Sagrada Familia and other buildings of Gaudi. It was all so pleasant, sunny and unlike April in the England I’d left. At that time, I hadn’t seen Antonioni’s The Passenger[vii], and encountered the Port Cable Car by accident without money to ride it. But all this tourist sightseeing, for which I couldn’t summon the mood, began to get me down. Finally, overcome by the rage of sheer exasperation, I pushed past the burly guard on duty outside the parcel’s room, armed with some sort of machine gun, to retrieve my bike. I just didn’t care anymore. It was so obviously mine. I’d proved the fact half a dozen times. Who else in Barcelona could possibly own that battered black machine with its crossbar gear-changer? The piled luggage and saddlebags, rattling bike tools and week-old sandwiches – only faintly blue, that I’d later have no choice but eat . . . it was obvious we were connected. We’d criss-crossed Somerset and Devon, Dartmoor and Cornwall together – hundreds if not thousands of miles. As Flann O’Brien would acknowledge – or at least one of his mad policemen[viii] – that Royal Enfield was 29% me and I was 29% it! If I’d believed in molecules, genetic codes and all that irrelevant bilge, I’d have suggested they took samples: Blood and chain oil. Hair and rubber. Skin and flakes of baked enamel. Or tried a fingerprint kit: blown up, magnified – my prints curved round, would surely have matched its tyre treads?

Anyway, not caring for the bullets, I pushed past, and was soon on some older coast road above the container port. They just let me go. Convinced by my rashness perhaps? A mad dog of an Englishman caught in the midday sun.

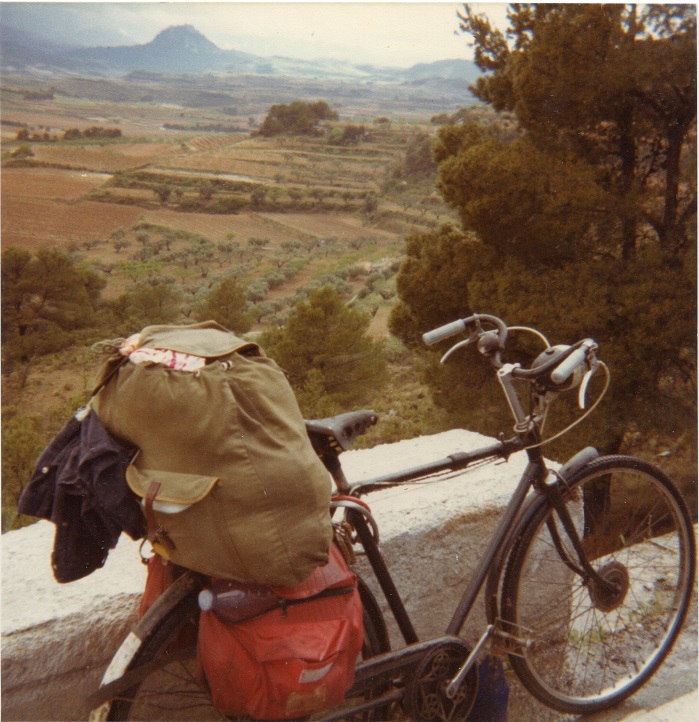

- The Royal Enfield, western edge of Barcelona, April 1986.

First time round, The Limits of Control appeared a clear case of style over content and I might almost have sided with Peter Bradshaw against a “colossally self-indulgent and boring film that only a successful and revered director could make”. On second viewing, I had no expectations and could use its spaces for myself. Is this what a whole genre of art attempts to do: grant you a certain kind of expansive space? The dream which (at 33.55), in another replicated café, Tilda Swinton claims could be film or dream, is clearly a reference to Tarkovsky’s part presentiment of Chernobyl, Stalker (1979)[ix] – an infinitely greater film, that also encourages, as does most subsequent ‘slow cinema’[x], an expansive space. Many of these films cannot help but raise the question (similarly hovering around much lesser and gimmick art like a vulture determined to pick meagre sustenance from bones), of The Emperor’s New Clothes . . . that fracture upon which so much art since the late 19th Century hangs. In some cases, it’s only the tension of doubt that energises the artwork in question, (just as the ‘perfection’ of any worthwhile art, often relies on its imperfections – explaining why so much classical art is simply uninteresting). Equally a lot of trash passes muster by trading on this ambiguity of doubt – employing sleight-of-hand rather than essential paradox. Erupting from internal human flaws via anger or self-disgust, such force occasionally gives rise to its opposite. All these tensions can take you to a metaphorical cliff-edge where you exist, apprehensive but euphoric, ready to fly or fall.

- The Royal Enfield, near Sitges.

Along older roads west of Barcelona, in a warm haze, I began to recover, perching to eat the old sandwiches on a dramatic coastal overhang before Sitges.

Next day, somewhere after Tarragona, appalled by the chain of Spar shops along the coast, I turned inland. And then the weather changed. I’d left the beaten track and was soon on mountainous roads with a useless map. The weather was going to have a laugh at my expense. Violent thunderstorms between occasional manic bursts of sun alternated as I headed west and north, crossing the Ebro in violent spate, shortening my projected route for lack of funds, increasing the mileage because I no longer trusted the confiscations of trains. I was soaked through and dried out a dozen times before the resolutely higher ground of the Pyrenees brought snow and chilling fog. In the morning, my tent zip was iced shut. The border had only just opened and they were thinking of closing it again. The descent was perilous and freezing. Without snow poles the position of the road would have been unknowable in the white-out. It was just as well it was too cold to ride, since had I tried, I could not have stopped. Living in the North Pennines years later, the easy solution to stopping in snow was to throw yourself into the drifts by the side of the road. There I knew the roads. Here I didn’t. I couldn’t see any crash barriers there might be – in those days the roads seemed mostly to be battlemented – blocks big enough to stop a car, but lovely inviting gaps between. Gaps just right for bikes. Nothing between you and dropping rocky space.

- Royal Enfield in the Pyrenees.

I used to worry about death a lot. Literally from the age of five. Especially at night. Until recently, this anxiety could persist in an intense form for weeks. I’m not sure when this fear began to fade or whether the change means anything, but it feels positive rather than resigned. Perhaps one part of myself has finally persuaded the others that la muerte will be good? It had bloody better be, you might say – because life definitely isn’t all it’s cracked up to be! There may be a lot of beauty in the world (and love will often make things worthwhile, as James Mason’s Flying Dutchman eventually discovers with Ava Gardner’s Pandora), but injustice, poverty, ill-fortune, poor health… all occur randomly. Few get what they deserve and the leading lights and fires of society are an equally haphazard bunch – the majority of them corrupt, useless, or plain evil.

- Nothing to overtake or be overtaken by, April 1986

Foreshadowed by the empty house with dustsheets, under one of which Paz de Huerta lies either sleeping, dead or lost in her imagination, The Limits of Control, (Slow Cinema ‘lite’ perhaps – a phrase I hate but will stoop to in humorous rather than essential, paradox), begins to wind down in a Madrid Gallery by Tapies’ Gran llençol[xi] (102:27). Here, the Emperor’s New Clothes, may again give you a space created entirely by context: the contrast of vertical rigid sheet, hung in a site of reverence. If you remain calm, the space is not about the painting itself, which has no intrinsic value. It offers a blank slate. The space comes from what you form in thinking about it; in trying to prise or sympathise meaning from it. This is true of a great deal of art, good and bad. To a greater or lesser degree, the art relies on you. The very best art exists to inspire us to go beyond it. Ultimately, the art object itself is unimportant; it’s monetary value, totally irrelevant. Occasionally, even gimmick art can inadvertently launch the imagination due to the sheer paucity of its value. Provided we can engage our mind enough; provided we’re filled with enough detail, some territory beyond is certain to open up.

- Royal Enfield crossing the border (actually Somport) [xii]

With my old notebook lost, I couldn’t be sure which winding course through the Pyrenees I took. Few central routes breach the border, and less in 1986, would’ve attempted to stay open through winter. A 100-mile dead end would have been expensive, so it was lucky Col du Pourtalet stayed open – if it was really there I crossed? The image of the abandoned frontier in 2011 does not match my photo of twenty-five years earlier. Dropping the twitching, hanging, yellow servant of Google, Inc., from the sky into a world whose magnetic poles are so unstable, I followed the adjacent border crossings. To the west, virtually unacknowledged, the frontier comes amidst a series forested hairpins. To the east it occurs low in a valley. The way I took was bare and exposed: an obvious watershed.

Press-ganging the parachute-less man again, to advance along the road in sliding bursts – his broken legs aided by skateboard or erratic trolley perhaps – I can’t match the prospects, either to memory or my limited photos. 12 shots to a reel, a reel a week: my camera was as out-of-time as the Enfield. It doesn’t help that the 2012 surveyor traversed the mountains on a bright clear day. At the border in 1986 all the distances were close to whiteout, rock-faces and mountains invisible. There was only snow and mist, and most of all, memory struggles to revive my frozen hands.

The Enfield was better adapted. Oblivious to cold. Careless of lurking vertigo. Nerveless. Not mentally affected at all. It’s brake cables (at some time in its past replacing rods) were thicker and better made than later versions. They would never snap. I remember a place called Triste, a tiny hamlet strung near a lake. There the Enfield juddered to a stop, deliberately it seemed, a piece of stick jammed between wheel and mudguard. This must have been the following day descending into France. The stick was easily removed and for a while, a rare sun blessed the panorama and this Triste or tryst was bittersweet. An old photo has the place name written in biro on the reverse, and I clearly recall the short metal sign itself, yet can find no trace of such a place on any map – as if my imagination made it up. As if the whole episode is a variety of fugue or ellipsis, a parallel world to prevent mental disintegration. A balm, or hope for the future. A link to some alternative life. The idea of this place (and there are others in similar vein – as though my mind is slowly building, unrequested, an entire imaginary map), haunts me as if it were the very centre of a maze. I sense that if I could grasp its reality firmly enough, the true landscape around it would slowly come back to life, replacing the blurred, greyed-out suburb of the comparative nowhere we inhabit. It haunts me as though I did not stay there long enough – and now will never find it or its equivalent again. As though, more than anything else, more than any art, philosophy or religion, it indicates a simple way to break through the entire illusory fabric of this world; of so-called reality, itself.

- Triste. French side of the Pyrenees. April 1986.

As with Tapies’ in itself pointless, ‘Gran llençol’, one can charitably take Jarmuschs’ film as a meditation and opportunity for lateral thinking. From a certain enjoyable undemanding ambiance of hollowness, in a universe with no centre or edges, the viewer is forced to find themselves – if they still have a self to find. Unfortunately, this possible gift is always likely lost on mainstream audiences.

It seems strange that people, albeit grudgingly, still feel obliged to respect the old classical art that clogs museums, particularly perhaps the marble variety. Obviously, such art can be beautiful (and is ideal for monuments and garden ornaments), but somehow the surface flawlessness of such object d’art for me has become a symbol of Establishment. Even the worst gimmick art is at least kicking obstreperously against this vast world-numbing Establishment – a noisy kid, faced with a pedantic stone figurehead.

With elevation declining, it began to rain. All the way to Mont-de-Marsan and on through the endless Landes forest it rained and rained and rarely stopped. It was around then that Chernobyl went up and I wouldn’t have known but for two French teachers on a cycle with a small class group. Well-equipped, they were making the most of a brief window of sun – the same pause in which I attempted to dry my sleeping bag on a fence beside the road. Kindly they invited me for dinner that evening and we discussed the hubristic folly of nuclear power – a folly still espoused, it’s hard to believe, by over-confident half-wits more than thirty years and far too many permanently serious accidents later.[xiii]

What if in the end, only the imagination is important? That we have grown and evolved physically, only to allow the imagination to advance far enough to give us everything. The remembered riverside at Chiswick in the 1950’s can be more important to my Dad than anything else – and perhaps that’s as it should be. What could be better than the best moments of one’s own past, burnished to a perfect glow, the anxieties of their times evaporated, the frustrations of ambition released? Does this not approach Pascal’s ability to live happily in a room alone?

After death, hopefully we can exist without tiresome bodily and mental restrictions? Such literal escapism may be nonsense, and I do admire and appreciate the attempts to create heaven on earth that various individuals and groups have struggled to bring about. But even my ideal of some anarcho-socialist community of liberty and equality, sustained by workers co-ops and a strong belief in harmless eccentricity, can only be temporary . . . and permanent death is unacceptable! It’s true that underdeveloped personalities might descend via imagination into violence and pornography, high-speed driving and thrill-seeking – all those situations that abound in mainstream cinema. But just think for example, how in dreams, the imagination can create flight and endless movement through time; can create both love and surety, perfect worlds where things are done ideally. Think how dreams can change events and allow us to see the things we should have done; make landscapes perfect and bring back the dead. What possible harm can it do to believe in the eternal extension of the imagination?

By contrast what good does it do the average person to conform to the beliefs of science and the rational world? Most have never been required to understand the things they use: be it the fire, the car or the latest technology. Increasingly, to be such a human of renaissance is impossible. We all must specialise in our own restrained area of truth. It does not matter whether the sun goes around the earth or vice versa: such knowledge is all just junk in the attic, to paraphrase Sherlock Holmes – a character more real than his creator!

As town centres and travel have been homogenised, so have the underlying beliefs of society, which like it or not is rationalist and materialistic. For all but the most devout, religions are no longer more than a surface dressing. Instead, obediently, most of us worship science, just as our forebears trailed their controlling and congested illusions. Yet the scientific grid of interlocked, self-fulfilling prophecies, are not built on an unchanging foundation, but rather are entirely subject to the filtered or extended ‘proof’ of our five basic senses. Its whole basis could shift at any given moment. Its certainties are as limited as any, and just as ultimately irrelevant. Its truths are as insubstantial as Paz de Huerta’s transparent raincoat; as conformist as the football kit that provides Issach de Bankole anonymous camouflage of escape, at the close of The Limits of Control.

- Royal Enfield on Battlemented Road. Catalonia. April 1986.

So what is there left to believe in, in this world we have poisoned? How is it possible to suspend disbelief?

Apart from a little light housework, science doesn’t do a lot of good. No doubt, while we’re around, it’ll continue to be useful at a superficial level. But even could it have expanded the way its leading practitioners might reasonably have hoped, it would have remained controlled by the corruption of governments and worse, by the grasping of multi-national companies who don’t want their terminal monopolies broken.

There’ll always be hope in people themselves; in idealist political action, in ecological groups and the recent petition organisations – which have found a rare worthwhile validation for the internet. But all these things are rightfully concerned, mostly with avoiding a hell on earth. If, as individuals, we don’t want to be buried in the ruins of dogmas or the constricting coils of scientific schemes, what is there beyond this life to believe in? Such a question might seem old-fashioned, but without something extra to believe beyond the mess we have made, it would be hard to bother at all. Even if it is rational and modern to draw the line at death, such narrow-mindedness is undoubtedly damaging. The greed of believing too much in this life, this now, far from enabling us to strive for some heaven on earth, has only had the opposite effect. The big grab has been bred into us. Grab all you can get NOW. Live the moment, grab it NOW, and stuff the next generation! Sadly, this is where the religion of science has lead us. Like all religions, it’s potential purity was easily corrupted.

For myself, I choose to believe in the freedom and reach of the imagination. This is not escapism. It’s a harder faith to hold than that of material comfort. But I’ve no draconian desire to put my belief into dogmas, whether or not – as a philosophy that disregards race, health, gender, beauty or wealth – it would be better to try. I choose to believe in that beyond which the highest art suggests . . . and where perhaps many of the multitudes of lesser attempts lead by default – by the heat of our contempt, by the sharp ramp, by the necessary leap we’re forced to make to find meaning in them.

For those lumbered with a belief in evolution – the unfortunate path that’s been so lethal to the Earth – imagination could easily be projected as the next stage. The wisest religions have always avoided trying to name or define God, and no human can fully comprehend infinity or eternity. Therefore, that a metaphysical belief in imagination, unlimited by the undermining of physical constraint, suggests solipsism rather than connectivity, need not be a worry. The furthest unfathomable reaches of anything worthwhile, can obviously only be intuited. Science by contrast will always be defined by the essential control it’s forced to pretend; by the limits of mathematical intelligence. As a boy, I loved the universe and the stars, and though the largely monotheist teachings of science tried to destroy that for me – tried to turn it into a vast backyard of depressing emptiness – every time I look out at it now, through the star grids and projecting beyond, I can easily disregard their petty rules. Through imagination, I can get back the magnificence I once felt a part of – back in the days beyond the limits of control.

Lawrence Freiesleben

Notes and References (all links accessed between November 15th & December the 7th 2017):

[i]www.youtube.com/watch?v=MU4_bJT8W3Y (Radiation fallout over Europe during Chernobyl incident (1986)

www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sfl5wZw0AME (Facts About Chernobyl Disaster)

[ii] Although as I went down from 11 and half to just over 8 stone during the trip, my body might disagree!

[iii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Shock_of_the_New

[iv] www.theguardian.com/film/2009/dec/13/limits-of-control-review Philip French

[v] www.theguardian.com/film/2009/dec/11/the-limits-of-control Peter Bradshaw

[vi] www.imdb.com/title/tt0043899/

[vii] www.imdb.com/title/tt0073580/

[viii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Third_Policeman

[ix] www.imdb.com/title/tt0079944/

[x] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slow_cinema

[xi] Tapies’ collage and painting on canvas: www.museoreinasofia.es/en/collection/artwork/gran-llencol-large-sheet

[xii] After finishing this tract, I discovered from the similarity of this photo of mine, to an image stumbled on by accident, that it must have been the Somport Pass I took – a route since superseded by a controversial tunnel.

[xiii] Driving along the Cumbrian coast the other day I discovered that, in the manner of Devon and Dorset’s Jurassic Coast, someone or some committee has had the nerve to christen the area, not the polluted or fluorescent coast, the dicey or even just the questionable coast, but “The Energy Coast”! – a cover-up which reminds me of the many aliases conferred upon the Nuclear reprocessing plant at Windscale, or is it Seascale, or Drigg? No, it’s Sellafield! Presumably, Nuclear Power is still considered such a ‘clever’ idea that we won’t drop it until it kills us?

P.S: I’m reliably informed that “The Energy Coast” also refers to off-shore wind turbines and other genuine renewables, so I withdraw at least half of my righteous indignation.

[…] [i] http://internationaltimes.it/the-limits-of-control-a-spanish-digression/ […]

Pingback by Places (Not) to Rest – A Virtual Pub Crawl, Then & Now Part 1 | IT on 9 May, 2020 at 6:19 am