In Heathcote Williams’ early works you can usually find Jesus…but it’s unlikely to be the Jesus you were looking for.

The Speakers, Heathcote’s first book, is a wily autofiction and the character named “Cafferty” immerses himself in the society of Hyde Park’s Speakers Corner in the 1960s. The Park’s habitués that he portrays include the unclassifiably deranged, the fanatical, the logorrheic and the frequently drug-fuddled. In the background, a chorus of transvestive “West End queers” with sobriquets like Caligula and Mary Pickford, dodge the police and mingle with the hecklers.

There is also Harry, who drags a crucifix across town, ornamenting it with discarded waste: stale bread, quoit rings, rubber tubing and tattered ribbons. Laying it flat on the ground he uses a clear space of timber to stand on his head and when this attracts sufficient attention, he rallies his audience with the opening: “I am the plenipotentiary of the century, I am the interpolator of interpolaters, and I am THE Messenger with THE Message…”1

Billy MacGuinness, one of the four main speakers Heathcote profiles had also once adopted the Christ complex and gone on a pilgrimage to Liverpool with a cross on his back. After being arrested he spent exactly seventy-two hours in jail, the length of time Christ was in the tomb, then arose to his mad Gypsy life once more. Heathcote fondly remembered Speakers Corner as the perfect place for, “…speaking in tongues, speaking in the wilderness, the Sermon on the Mount, the trickster, the fanatic, the holy fool.” 2

The Speakers was followed by his one act play The Local Stigmatic, where a vain, dull and innocuous minor film actor is ritually assaulted, and then “stigmatised” with a slashed and punctured face.

Next, in AC/DC, the therapeutic experiment conducted on three Christ fantasists is reinvented as a ritual of mass-media sabotage, intensified by orgasmic self-flagellation.

In “Fry the toad of Nazareth” 3 Heathcote mimicked Lord Buckley’s jive patter, specifically taking off “The Nazz”, Buckley’s hep Jesus routine. 4 The gospel according to Heathcote, however, was a scatological scat on the Passion.

In “Fry the toad of Nazareth” 3 Heathcote mimicked Lord Buckley’s jive patter, specifically taking off “The Nazz”, Buckley’s hep Jesus routine. 4 The gospel according to Heathcote, however, was a scatological scat on the Passion.

“Once upon a time there was a cat named Simon Magus. He was the leader of a gang of skank werewolves and sex terrorists known as the Essene Gang who ripped and roared and sucked and fucked their way through Israel in the year boobety-boo…”

Gnostic magician Simon is the star of Heathcote’s sermon; drawn from stories in the apocrypha where he and Christ are portrayed as competitors on the miracle worker circuit. They tussle for top billing, dispute the provenance of being God’s son and, besides his levitation show-stopper, Simon has a trick of raising the dead by “giving them head”.

“Fry the toad…” was published two years before James Kirkup’s more conventionally composed “The Love that Dares to Speak its Name” appeared in Gay News. The precedents for Kirkup’s poem are the erotic verses of ancient Greece (all theia mania and mortals coupling with deities) and the French Decadents. His homoerotic Christ and the necrophiliac passion of a Roman centurion became famous when its British publisher, Dennis Lemon, was convicted of libellous blasphemy.

Kirkup has his centurion ponder on a swinging Christ that had previously “had it off” with Paul, Judas, John the Baptist and Herod, a similarity that suggests he had seen Heathcote’s work. It’s a safe bet that the trial prosecutor hadn’t. He declared that Kirkup’s poem was, “…so vile that it would be hard for the most perverted mind to conjure up anything worse”. 5 If he had only known.

<>

In August of 1968, Heathcote drew me into one of his intrigues and for a several months we shared a series of taxi rides across London. Setting off from the Transatlantic Review offices in Kensington we went to Shoreditch and the Old Street Magistrate’s Court. The trial sessions we attended were for three men who had been charged with grievous bodily harm after crucifying an interior decorator on Hampstead Heath. The crucified decorator (and small-time stage illusionist) was named Joseph de Havilland and also on trial, accused of importuning a criminal act.

Heathcote wanted to record the trial and had obtained what was, at the time, a sophisticated tape machine that could be worn on the body. A small microphone was attached to the recorder through a wire down the sleeve and concealed under an expensive, gentleman’s overcoat.

This was possibly the Crombie that he mentions in The Speakers, the one that MacGuinness asked Cafferty/Heathcote to lend him. “I could get anything with a Crombie coat,” he argued, “I’ve got to have a front. Are you with that? – They think their pound notes are God, and MacGuinness is going to turn them into atheists.”

At Old Street, Heathcote considered a similar, disarming show of respectability was necessary since the use of a recording device, even carrying one into a courtroom without permission, was contempt of court. Getting caught was potentially worth a few months in prison. The tapes only recorded around 30 minutes per side and needed to be changed, sometimes several times, during each session of the trial. Whenever Heathcote fiddled suspiciously inside his coat, I was supposed to screen him and to cough when the cassette clicked off and on the mechanism.

De Havilland didn’t claim to be Christ returned, but declared that his crucifixion was an act of spiritual martyrdom, directed by supernatural beings that came to him in visions. One of the men who nailed him to the cross testified they were going to make the world “a happier place” and de Havilland’s suffering would bring about the end of “sin and racial discrimination”. Instead of Jesus he cited the recently assassinated Martin Luther King.6 7

Their story didn’t impress the prosecutor and he argued that the real motive was to make money from selling photographs, presumably through a secret network of sadomasochistic fetishists.8

Whether the purpose was algolagnist porn, or the delusions of halfwit cultists didn’t seem to matter to Heathcote; he was more interested in the choice of David Jacobs as the defending lawyer. Jacobs usually worked for show business clients and when he appeared in court at some of his glitzier cases was known to slap on a bit of makeup.9

Heathcote told me that one of Jacobs’ past clients had been the chiropractor, portrait artist and totty procurer to the gentry, Stephen Ward. When his trial for living off the immoral earnings of Mandy Rice Davis and Christine Keeler was coming to the end, Ward committed suicide. Some people weren’t so sure he did. During their de Havilland trial investigations, the police questioned Jacobs himself and when the case was over, he signed into the Priory clinic for mental health reasons. Shortly after he came out, he also committed suicide. Some people weren’t so sure he did either.

The trial recordings were going to be used as part of a play at Jim Haynes’ Arts Lab, but as far as I know this was never completed or performed.10

<>

In 1968 Heathcote and Diana Senior moved into the basement of a townhouse in Bayswater. Their first daughter, China, was recently born and they had received a parcel of hand-me-down baby clothes from Los Angeles; courtesy of Frank Zappa. At the bottom of the outside steps, the ones originally for use by tradesmen and servants, Heathcote had removed the lock of the under-steps coal store door so that a local rough sleeper could bed down inside.

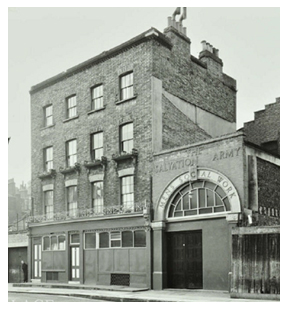

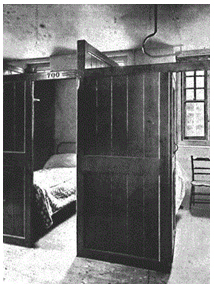

This may not have been the first time that Heathcote acted on his concern for the homeless, but it was unlikely that what became a missionary zeal began with the pastoral guidance he received at Eton. It more likely formed in the years he was shadowing the semi-vagrant Hyde Park speakers and frequently had to live in London’s dosshouses. Among those were the Salvation Army Hostel on Lisson Street and Rowton House in Newington Butts. The Newington workhouse, built in 1916, was vast and grim looking and faced over the local church graveyard. The road that ran behind was named after Dante, who had depicted the anguish of souls trapped in Limbo. Any hope of a pardon from that first circle of hell depended on the intercession of Jesus.11

This may not have been the first time that Heathcote acted on his concern for the homeless, but it was unlikely that what became a missionary zeal began with the pastoral guidance he received at Eton. It more likely formed in the years he was shadowing the semi-vagrant Hyde Park speakers and frequently had to live in London’s dosshouses. Among those were the Salvation Army Hostel on Lisson Street and Rowton House in Newington Butts. The Newington workhouse, built in 1916, was vast and grim looking and faced over the local church graveyard. The road that ran behind was named after Dante, who had depicted the anguish of souls trapped in Limbo. Any hope of a pardon from that first circle of hell depended on the intercession of Jesus.11

Considering that The Speakers was published when Heathcote was 22 and the publisher claimed that he had been researching and writing the book for five years, his experience of a disenfranchised underlife started at a tender age. Or maybe it really began in the all-male boarding schools he attended, originally at Wellesley House at Broadstairs. He was at Wellesley for five years and when consigned to the place for the initial seven months, foresaw the “oppression” ahead as, “compulsory Greek, Latin, Verse Composition, Caesar’s Gallic War, Precis, Prep, long pointless walks in strict crocodile formation down to the stone gap and back, religious services conducted in cold gymnasiums and an inedible gelatinous meat composition called Brawn.” He and his new school mate, Prince William of Gloucester, were both homesick and missing their parents, and burst into tears.12

Considering that The Speakers was published when Heathcote was 22 and the publisher claimed that he had been researching and writing the book for five years, his experience of a disenfranchised underlife started at a tender age. Or maybe it really began in the all-male boarding schools he attended, originally at Wellesley House at Broadstairs. He was at Wellesley for five years and when consigned to the place for the initial seven months, foresaw the “oppression” ahead as, “compulsory Greek, Latin, Verse Composition, Caesar’s Gallic War, Precis, Prep, long pointless walks in strict crocodile formation down to the stone gap and back, religious services conducted in cold gymnasiums and an inedible gelatinous meat composition called Brawn.” He and his new school mate, Prince William of Gloucester, were both homesick and missing their parents, and burst into tears.12

The upstairs of the Bayswater house was occupied, I think owned, by one of Heathcote’s friends from Eton, Peregrine Eliot (later to be Earl St Germans) and he once came up with an idea for a mechanical ice-cube dispenser that could be mounted on bar tops in pubs and clubs. The option of ice cubes in drinks was less common in English pubs in the 1960s but American tourists and transatlantic commuters meant that demand was growing.

Heathcote invited me around for an inventive afternoon and when I doubted that I would have much to contribute, he laughed and said, “Just go along with me” a line I recognised from Local Stigmatic. I got the impression he was trying to humour Peregrine and the three of us spent a few hours, smoking dope and doodling on large sheets of paper. In the end we had only produced some strange shapes with an idea of where the water went in and the cubes came out.

In the short time that I had lived in England my experience of aristocrats was limited and I was surprised that the first one I met was interested in fast-buck gadgets. I assumed that Peregrine was from the sort of landed-gentry the Labour government had taxed into selling off their old masters in order to fund the new egalitarian society.13

<>

The originality displayed in The Speakers, and Heathcote’s subsequent two plays, was widely admired by his contemporaries. Following AC/DC’s acclamation and awards, the Royal Court’s Artistic Director, William Gaskill compared him with Congreve, as a “deliberate literary craftsman”.14 Nicholas Wright, who directed all three original stagings, described the play as “a virtuoso flight into liberation politics.”15

What came next, pieces that formed the plays Remember The Truth Dentist and The Supernatural Family, was a flow of feral polemic, often artless and blunt on subjects like sex, death, taxes, private property, plant consciousness and god. Frequently the tone was proverbial…

. “God made man in his own image but is starving from lack of feedback.

God is high, even when he comes down.

God can stare you inside out.

God gets jealous when religion gets too sexy…”16

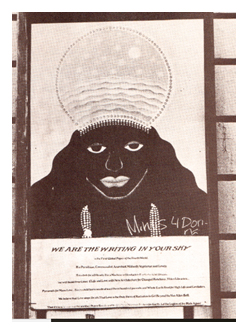

…but could come across as rousing, scolding or huckstering. Some lines had a zap akin to the rants of AC/DC’s madhouse tea-party, but generally there was little distortion and mystery, the indicative textual difficulties expected in the literary avant-garde. Sometimes he didn’t hit the mark, but that was also the point, an equal opportunities’ act of personal outrage and/or ecstasy, encouragement for anyone to fling their thoughts up on the wall or into his people’s poster newspaper, We Are The Writing In Your Sky. One boozy afternoon we agreed that John Bull Printing Oufits were all that were needed to turn every banknote that passed through anyone’s hands into a personal medium for revolutionary wit and dissent.17

Sometimes he didn’t hit the mark, but that was also the point, an equal opportunities’ act of personal outrage and/or ecstasy, encouragement for anyone to fling their thoughts up on the wall or into his people’s poster newspaper, We Are The Writing In Your Sky. One boozy afternoon we agreed that John Bull Printing Oufits were all that were needed to turn every banknote that passed through anyone’s hands into a personal medium for revolutionary wit and dissent.17

On one side, Heathcote’s eloquence, charm and cultural acuity were formidable. On the other there was Speakers Corner with its weirdos and trawling rent boys, the dosshouses, the photo finish scams at the Romford greyhound racing track and wasted days in dives like The Kismet, an afternoon drinking den known by patrons as ‘Death in the Afternoon’. A club regular was once asked: “What’s that smell in there?” His reply was, “Failure.”18 One of Heathcote’s Soho boozing friends was a Kray Gang outworker with the novelistic name of Johnny Quarrel.19

<>

“Now Christine Keeler as one of MacGuinesses’s ex-mysteries has done more damage to the British government than the Labour Party, the Mau Mau or the I.R.A. have done in the past forty bloody years…Prostitution has not been and NEVER WILL BE a crime. Christine Keeler is a MODEL, like MacGuinness. Anyone can come up to my caravan and I’ll pose for you any night of the week.”20

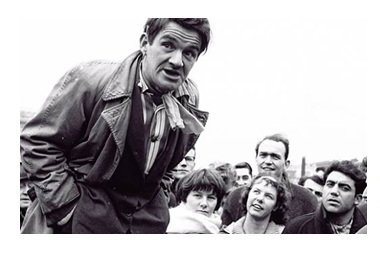

Of all the Hyde Park speakers, the “Black Irish”, amphetamine-fuelled MacGuinness, whose usual appearance was “unshaven, ragged, stained and toothless”,21 was the one that Heathcote most admired. For a while they had shared a dingy room on Greek Street in Soho. After MacGuinness’ death, around 1967, Heathcote thought he had picked up a left-behind “aura”. “When you’re close to somebody, you become rather similar to them, when they die.” 22 We may never know but it’s worth wondering if he ever took his Truth Dentist “revue for one man” to Speakers’ Corner and tried it on the punters. In The Speakers, Cafferty/Heathcote is asked several times when he is going to get up on a box himself and say something. By the book’s end, he still hadn’t.

Of all the Hyde Park speakers, the “Black Irish”, amphetamine-fuelled MacGuinness, whose usual appearance was “unshaven, ragged, stained and toothless”,21 was the one that Heathcote most admired. For a while they had shared a dingy room on Greek Street in Soho. After MacGuinness’ death, around 1967, Heathcote thought he had picked up a left-behind “aura”. “When you’re close to somebody, you become rather similar to them, when they die.” 22 We may never know but it’s worth wondering if he ever took his Truth Dentist “revue for one man” to Speakers’ Corner and tried it on the punters. In The Speakers, Cafferty/Heathcote is asked several times when he is going to get up on a box himself and say something. By the book’s end, he still hadn’t.

That jazzy stride and anticipation that Heathcote often wore coming down the street, brought back the only time I met MacGuinness, when he sashayed along, not quite five foot nothing of him, into Piccadilly underground station. My companion was also Irish, an art student who was persuading me to go down to the Tate Gallery and experience the power of JMW Turner’s paintings in the flesh. When MacGuinness appeared at the foot of the stairs, looking like he owned the place, my friend declared in a voice that rang around the tiled hall, “Will ye look who it is now…the King of the fekking Gypsies!” As it happened, the King was on a mission to score his pills, so the meeting was brief and left us both a few shillings lighter.

Whatever vestige of MacGuinness that Heathcote inherited it included pieces of his repertoire, including lines like, “All the great men are dead or in the madhouse. Oscar Wilde is dead. Omar Khayam is dead. And I’m not feeling very well myself.” Jean Shrimpton remembered him saying that, from the night they first met.23 In The Local Stigmatic Graham says, “I never pay for sex Ray, because Jesus Christ paid for our sins.”

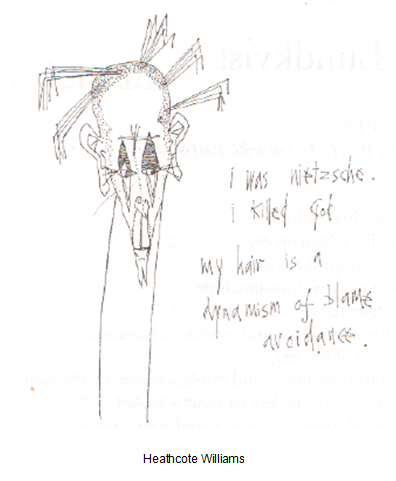

The writer and editor Francis Wyndham, a friend that Heathcote held in special regard, once wrote how much he disliked the “pornographic” content in Heathcote’s writing; that the use of it in attacking the establishment, whether royalty or politicians or the laws he didn’t agree with, was “an irrelevant weapon” and “puzzlingly inconsistent” when used by someone who claimed optimistic utopian beliefs and who had considerable literary gifts.

………..“But my argument gets nowhere. Heathcote scowls prettily, tosses what can only be called his ‘unruly curls’, accuses me of being an irredeemable media turd and a closet Monarchist…he excels at writing about alcoholics, schizophrenics, junkies, tramps. Accidentally contemporary with such movements as flower power and the drug culture, he became in a sense their Savonarola, embracing their cause with a passion, energy and rigour conspicuously lacking in their other devotees.”24

In an extended poetic reply to Inland Revenue, when he was asked for seven years in back taxes and £300 in fines, Heathcote declined to pay, “…until literary fame and copyright is smashed and literature becomes the dangerous little service organisation it once was.”25

It was impossible for Wyndham to have missed the spirit of Diogenes in Heathcote’s writing or his misbehaviour: the time (at least one) when he stripped off his clothes in a supermarket, the disorderly conduct in the Tate Gallery, the whisky bottle shattered against the wall in Giles Gordon’s apartment and the night he brought a reeking beggar to dine among the elite at Mr Chow’s restaurant when Wyndham had invited only him and Jean Shrimpton. One of Heathcote’s favourite Notting Hill characters was a large and silent Jamaican rough sleeper who wore all his worldly goods; several layers of never-removed clothes. The outer shell was a grease and grime caked greatcoat. Sometimes he would stand on the corner with a distant and contented look in his eyes. Heathcote said this was when he was having a piss.

Diogenes’ list of renunciations included family, wealth, politics, property rights and personal reputation. There are tales that he urinated on people who upset him, which Heathcote was reported to have done during the filming of Derek Jarman’s version of The Tempest. Sitting at a table in Stoneleigh Abbey with other members of the cast during a break, he thought they had relied on him “entertaining” them for too long without reciprocation. He climbed onto the table, a suddenly vengeful Prospero and dropped his pants, dousing the actors as they fled. For Diogenes, dogs set the right example, performing life’s natural functions, including sex, in public, eating whatever came their way, sleeping in whatever barrel they found empty.

“I dreamed I saw Diogenes

in a world reduced to rubble

and the founder of the cynics grinned

through his stench and unkempt stubble…”

The poem begins…and at the end Heathcote spells it out:

“Diogenes was and is the ultimate reality check; people aren’t meant to live the way that they do. Life isn’t meant to be slaved away and lived under the shadow of celebrities and media. Reality isn’t what the governing oligarchies and the oppressive plutocracies make it out to be. Mercifully Diogenes can leap across two and a half thousand years of time and subject it to his telling lacerations.”26

<>

In the early 1970s, Heathcote and Diana were back together and living in London’s Notting Hill on Westbourne Park Road. They had squatted a number of somewhat desolate rooms above a shop that also became the base of the Ruff Tuff Cream Puff estate agency. It was where Heathcote set up his bowl of money with the sign that read, “Take what you need – the rest is greed”. After selling a poem for the preposterous sum of £100 the idea had come to him, and he converted the payment into change to fill the bowl.

The property was often congested with dropouts and nomads, some not only expecting suggestions of places to squat but that Heathcote and his “estate agents” would do the breaking in. It was also a stopover point for writers passing through town – Lynn Tillman, in the midst of the European travels that included involvement with SUCK newspaper and encounters that fed into her book Weird Fucks, was checking out one of the days I came to stay. A few weeks earlier I had been offered the job of ghost-writing the “autobiography” of Christine Keeler. The suggestion had come from Running Man Press, a London publisher that I freelanced for as a book editor. Apart from an irregular semi-underground magazine, its small range of publications ran from Macrobiotic recipe collections to handbooks on sexual ecstasy. In 1971 the Obscene Publications Squad prosecuted it for publishing Paul Ableman’s book on oral sex. The book’s pornography turned out to be of little consequence but the marketing material, which had been sent via an unsolicited mass mailout, was found guilty. 27

The squat was unheated and barely furnished. Diana was doing her best to create some essential domesticity and had put potted plants on the window sills. Heathcote and I planned to discuss the Keeler project, but he disappeared for an hour or so and came back with bottles of cider and a group of admirers, young men who were encouraging his outrageous side, baiting the mad poet. It was a routine that Diana had seen before and wasn’t best pleased. In the morning she was brittle and defensive and even though I wasn’t the cause of the rowdiness and the broken pots, I apologised.

After she went off to take China to school, Heathcote came down and suggested we walk a few blocks further along Westbourne Park Road to the BIT information service office. BIT, Release and Ruff Tuff provided stand alone or co-ordinated advice for anyone that needed their help but were largely called on by diehard hippies and dropouts, many adrift in London looking for a version of the Play Power revolution that was already being asset stripped.

After she went off to take China to school, Heathcote came down and suggested we walk a few blocks further along Westbourne Park Road to the BIT information service office. BIT, Release and Ruff Tuff provided stand alone or co-ordinated advice for anyone that needed their help but were largely called on by diehard hippies and dropouts, many adrift in London looking for a version of the Play Power revolution that was already being asset stripped.

Before going into BIT Heathcote took me a little further down the street and pointed across to a closed-up shopfront. “That used to be the Rio Cafe.” It didn’t mean a thing to me, so he explained that it had been a coffee bar that was open 24 hours and mostly frequented by West Indians, a lively set that included dealers, pimps and hustlers. Once or twice the police had raided because of the gambling in the back room. Through the night pop stars and adventuresome Knightsbridge socialites used to drop in to score drugs and soak up lowlife thrills. “Make sure you talk to Keeler about it…Ward used to take her there…it’s where they met Lucky Gordon.”28

This turned out to be the only conversation we had about Keeler; the book project was cancelled a couple of weeks later because, I was told, the publisher’s lawyers had warned there could be lawsuits. It was likely that the British Government wouldn’t like it much either. I suspected the real reason was how much money Keeler wanted and soon after Running Man Press became dormant.29

<>

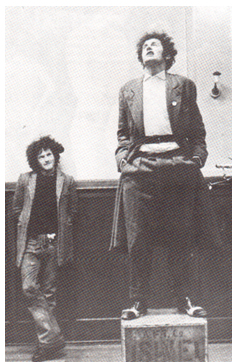

At the beginning of 1974 a play adapted from The Speakers, became the inaugural production of the Joint Stock theatre company. The original project was an experiment in new approaches to directing, a collaboration between Max Stafford-Clark and Bill Gaskill. The book was chosen as textual material for their first series of actors’ workshops; with its speeches and dialogue cut up and scattered around the rehearsal area to be used at random. To develop their roles the actors were sent out on the street to beg.

One of Joint Stock’s founders was the prolific playwright David Hare. After watching a full rehearsal of the performance piece that had been developed, he described (apparently without irony) the success of the production being due to the “absence of a writer”. 30

One of Joint Stock’s founders was the prolific playwright David Hare. After watching a full rehearsal of the performance piece that had been developed, he described (apparently without irony) the success of the production being due to the “absence of a writer”. 30

Staged promenade style, the audience milled among the actors and frequently had to choose which of the competing orators to listen to, or whether to “overhear” the comments of Cafferty and his fellow speaker-groupies. Enhancing the “actuality” of the experience, one actor operated a tea stall in the central area, serving cups of fresh tea and biscuits. The Speakers went down well on the initial tour, which included Amsterdam and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. At the Abbey Theatre in Dublin, some of the audience took to the immersive naturalism with an Irish fervour. They began heckling the “speakers” and assaulted an actor dressed as a policeman when he tried to “arrest” one of the orators. The Abbey probably hadn’t seen a decent riot since Sean O’Casey’s days and called in the Garda to restore order.

Heathcote’s original book had been praised by Samuel Beckett and when the play finally got to New York, Charles Marowitz may have had that in mind when he wrote a review for the New York Times:

“Human communion, or the best we can hope from it, is nothing more than a half mad Irishman confessing outrageous lies to a listening but heckling crowd. Life consists of helplessly spilling the beans to an inert, if rambunctious, crowd; a supercharged Vladimir reviling a multitude of Estragons, killing time by running off at the mouth, but mainly warming up a lost and anguished crowd for the touch which will pay for today’s booze…”31

The London magazine Plays & Players decided to give the production a plug and asked Heathcote for a statement, receiving a reply that ignored the play altogether: “The theatre is impotent. The theatre is stale hormones cooked up again. They can only cause damage …To perform is the artist’s homage to capitalism, which seduces you into producing instead of being, into thinking instead of praying, into vulnerability instead of purity, into sex instead of love. This is the only theatre that I can see: to quantify good vibes – they are alpha and theta waves, a mystic mixture – and ionise the air with them.” For good measure he threw in a message to Beckett, whose enthusiasm for the book of The Speakers had pleased him, but he now reacted to Beckett’s whinge that: ‘Every word is like an unnecessary stain on silence and nothingness’32 with the advice: “then shut the fuck up”.33

Jay Jeff Jones

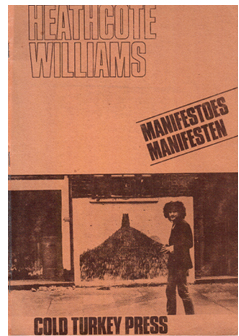

Post/crypt: Later in his life, Heathcote returned to Jesus. His poem The Last Foreskin of Christ, was published by Cold Turkey Press in 2011; and in 2013, The Anarchist Jesus (Parts 1 and 2) were recorded:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PiDcdTv5LZE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mg5vGQdvOqU

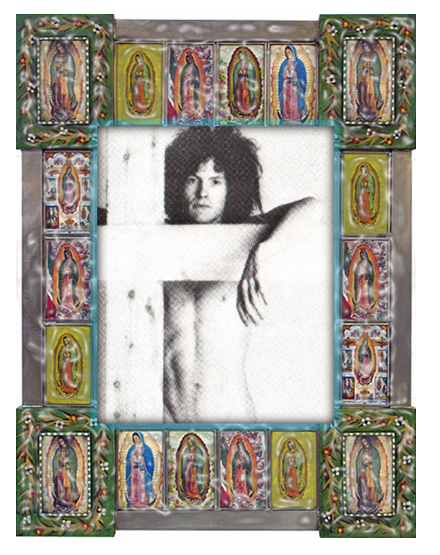

Images: Heathcote Williams and cross, SUCK, issue 8, ed. William Levy, Amsterdam, 1974; Heathcote Williams, Manifestos / Manifesten, Cold Turkey Press, Rotterdam, 1974; Salvation Army Hostel, Lisson Street, London; sleeping compartment in Rowton House, London; the first issue of the poster magazine We Are The Writing In Your Sky (the first global newspaper of the fourth world) fly-posted in Notting Hill, London, 1973; Billy MacGuinness at Speakers Corner, Hyde Park, London (undated); BIT Being newsletter, London: May 1974; Heathcote Williams watching Tony Rohr as MacGuinness in rehearsal. The Joint Stock Book, ed. Rob Ritchie, London, Methuen, 1987; Heathcote Williams, Transatlantic Review #50, London / New York: November 1974.

References:

- Heathcote Williams, The Speakers, London: Hutchinson,1964

- Heathcote Williams, A soap-box in cyberspace” The Independent, London: May 7, 1997.

- Heathcote Williams, Manifestos / Manifesten, Rotterdam: Cold Turkey Press, 1974

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U0x5x8lyON8&list=RDLHPrNCQQBvY&index=6

- John Sutherland, Offensive Literature, London: Junction Books, 1982.

- Glasgow Herald, September 1968

- Guardian, London: October 1968

- Associated Press Service, August 1968

- Jacobs’ clients included Diana Dors, Lawrence Olivier and Judy Garland. When the Daily Mirror ran a column that implied Liberace was gay, using terms like “quivering…fruit flavoured…mincing”, Jacobs helped him win libel damages.

- Jean Shrimpton in her book An Autobiography (London: Ebury Press, 1990) says that Heathcote continued his interest in the case and arranged to interview de Havilland. She mistakenly states that the Hampstead crucifixion was the basis for the The Local Stigmatic.

- Heathcote narrated Inferno and the other volumes of The Divine Comedy for Naxos Audio Books in 1996.

- SUCK, issue 8, ed. William Levy, Amsterdam: 1974.

Prince William of Gloucester was Queen Elizabeth II’s cousin and was once fourth in line to the crown. Born in 1941, he died in 1972 when the plane he was piloting crashed.

- Years later I found out that Peregrine had lost an expensive legal action in the early 60s. Brian Epstein, the manager of the Beatles, had been another of David Jacobs’ clients. Epstein asked Jacobs to look after the rights for Beatles’ merchandising material and Jacobs was persuaded by one of his nightlife contacts, Nicky Byrne (who ran a club in Chelsea), that the drudgery could be subcontracted to him. Byrne and a few partners, one of them being Peregrine, formed a company and then set up a United States subsidiary to tap the Beatlemania motherlode. Jacobs convinced Epstein to accept the outrageous split that Byrne wanted: 10% for the Beatles and 90% for Byrne and friends. Eventually Peregrine and another partner suspected that Byrne’s business and lifestyle “overheads and expenses” in America were consuming most of the profits and unsuccessfully took him to court.

- The Joint Stock Book, ed. Rob Ritchie, London: Methuen, 1987

- Nicholas Wright, 99 Plays, London: Methuen, 1992

- Manifestoes / Manifesten

- Years later Heathcote originated the idea of The Fanatic, a magazine whose name and masthead was up for use by anyone who wanted it. A number of individual issues were created, including ones by John Michell, Bill Levy, Willem de Ridder and Susan Janssen. A couple were published by Richard Adams and Heathcote and he and I planned one titled “Man Bites Machine” but we never got it to press.

- Christopher Howse, Soho In The Eighties, London: Bloomsbury, 2018.

- Heathcote Williams interviewed by Nancy Groves, Guardian, May 2016

- The Speakers

- The Speakers

- Heathcote Williams interviewed by Irving Wardle, Gambit International Theatre Review 18 & 19, London: Calder & Boyars, 1971

- An Autobiography

- “Francis Wyndham on the magic of Heathcote Williams”, London Review of Books, London: October 1979

- Heathcote Williams, “No I Will Not Pay Taxes”, Friends 16, London: October 1970

- Heathcote Williams, Diogenes of Sinope: Proto-Anarchist and First Citizen of the World, Rotterdam, Cold Turkey Press, 2016.

- Encyclopaedia of Censorship, ed. Jonathan Green, New York, Facts on File, 2005

- Aloysius “Lucky” Gordon (1931-2017) was a Jamaican born musician who briefly became one of Christine Keeler’s boyfriends. He became violently possessive and, in a fight with another boyfriend, Johnny Edgecombe, had his face slashed with a knife.

- Christine Keeler eventually published her story as Nothing but…, ghost-written by Sandy Fawkes, in 1983. It was adapted into the film Scandal! (1989) and she revised the story for further books including The Truth At Last, 2002 and Secrets and Lies, 2014. A new BBC drama series, The Trial of Christine Keeler, is due for screening in late 2019.

- The Joint Stock Book, ed. Rob Ritchie, London: Methuen, 1987.

In the production, Billy MacGuinness was effectively portrayed by Tony Rohr but the best MacGuinness portrayal, for me, was by John Joyce, in the Ken Campbell / Neil Oram production of The Warp.

- Charles Marowitz, “The Importance of Understanding Heathcote Williams”, New York Times, July 21, 1974.

- Gruen, John, “Samuel Becket Talks About Beckett”, Vogue Magazine, February 1970

- “Speaking Out: A message from Heathcote Williams”, Plays and Players, London: March 1974