Tish Murtha: The woman who fearlessly documented dereliction and decay in Thatcher’s north-east

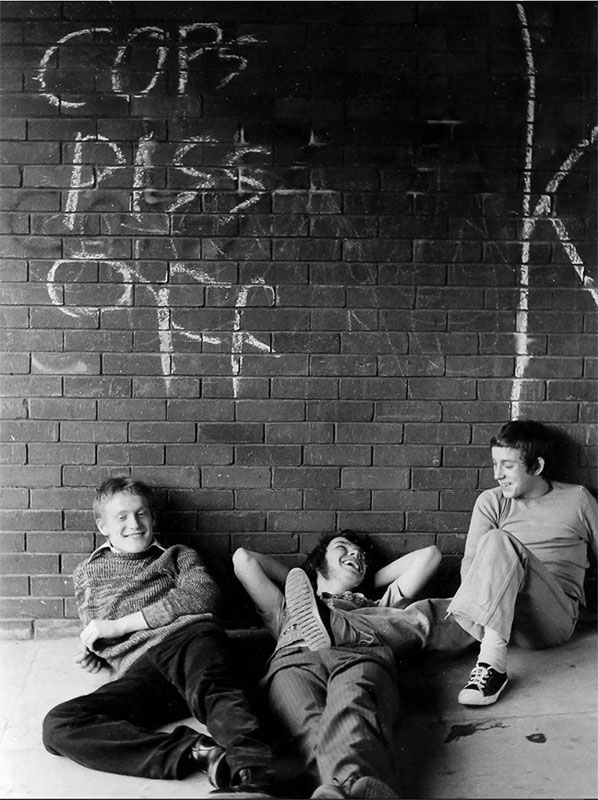

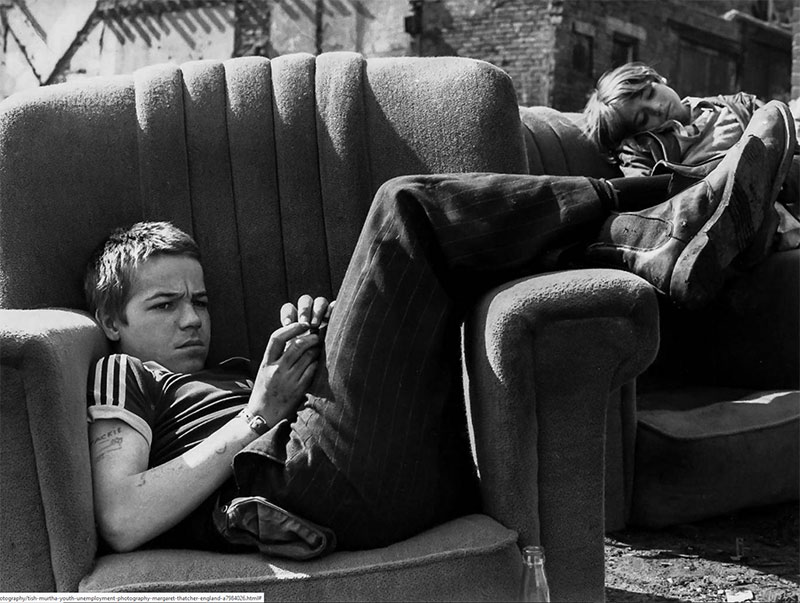

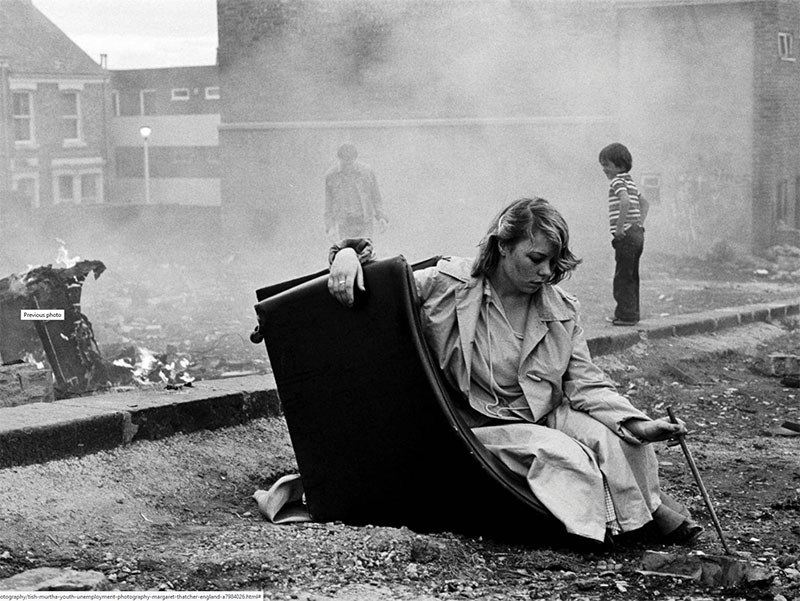

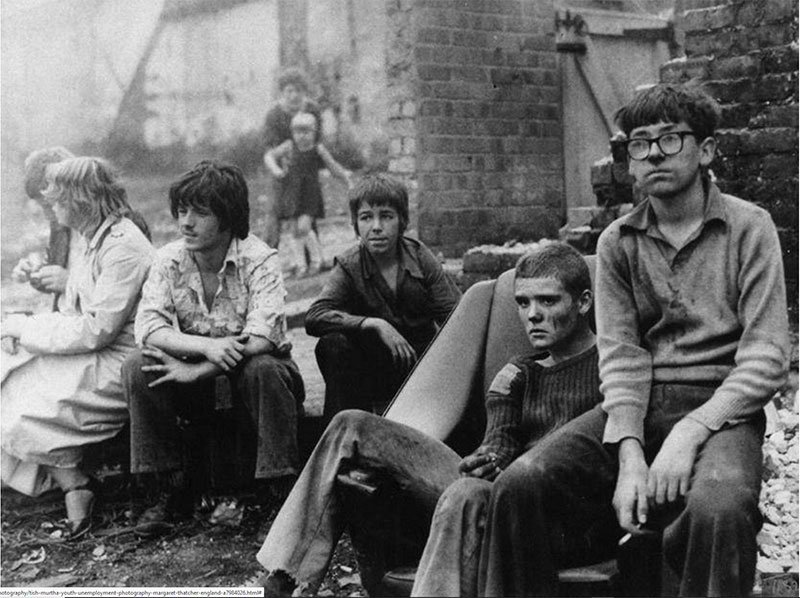

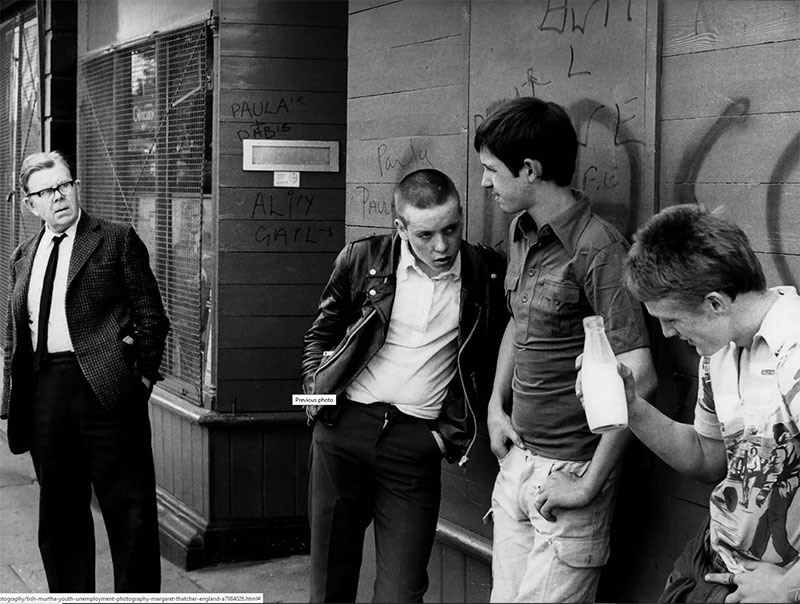

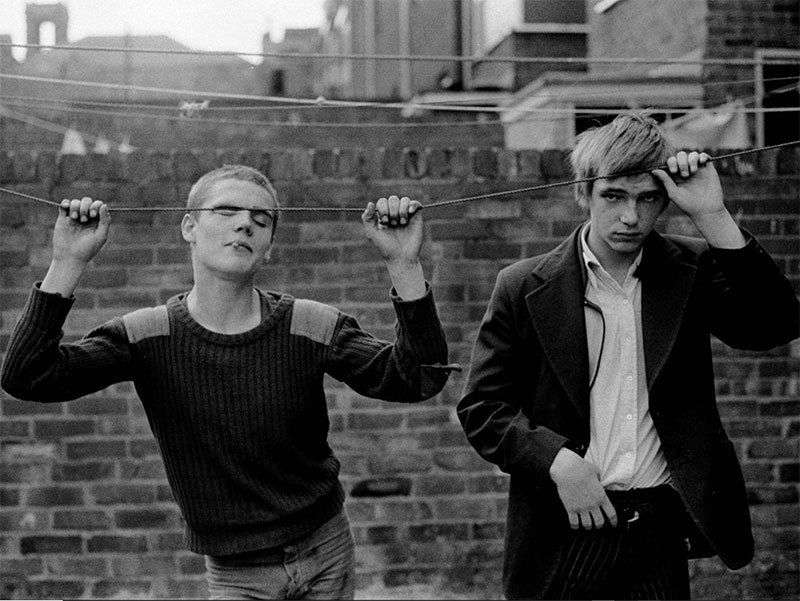

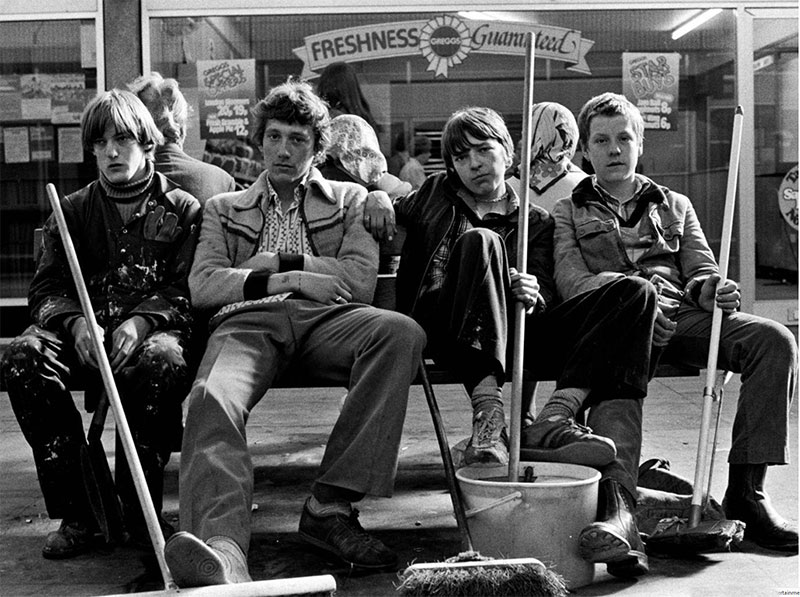

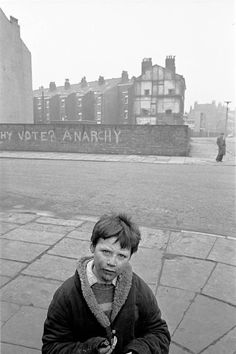

Capturing gritty images of imposed idleness and the ‘squandering of a whole generation of human potential’, the photographer, who died in 2013, provided an intimate glimpse into the dismal reality of growing up in 1980s Newcastle

.

“When the pressures of earning her living intensify, she swallows her prescribed tranquillisers and then slashes her arms with nails, razors or pen-knives,” photographer Tish Murtha wrote of a 20-year-old mother working as a prostitute in 1980s Newcastle.

The woman, who Murtha included in her essay “Youth Unemployment in the West End of Newcastle” nearly four decades ago, had been forced into sex work to support her young family when her temporary employment as a painter and decorator with a community project came to an end.

Stark and sombre this case may sound, but it was the reality facing much of north-east England’s youth in the Eighties, with opportunity scarce amid industrial decline and stagnation.

Murtha boldly criticised the Government of obscuring the true extent of the problem with schemes such as the Youth Opportunities Programme and claimed the function of statistics “tends more towards concealment rather than clarification”.

Incensed, she embarked on a crusade to capture and expose the true magnitude of deprivation and unfathomable inequality being felt in the region she called home.

The result was a series fittingly named “Youth Unemployment” – a staggering photographic dossier, capturing what Murtha described as “the area’s general air of dereliction and decay”.

The misery of alarming levels of youth unemployment and depressing six-hour waits at the DHSS office where one’s qualities were assessed in a one-minute interview, along with the anguish of being marginalised and discarded by society is palpable on the faces of those depicted.

.

This was, she said at the time, the effects of the “squandering of a whole generation of human potential”, “vandalism on a grand scale” all hidden behind “a smokescreen of cynical double-talk and pious moralising”.

Such was the impact of her work that it was raised as a subject of a debate in the House of Commons on 18 February, 1981.

Then-Newcastle upon Tyne West MP Robert Brown spoke of extensive business closures and mass victims of job losses as he endorsed the need for a Redundancy Fund Bill.

Her work and, in particular, her caution that “unemployed, bored, embittered and angry young men and women are fuel for the fire” for “barbaric and reactionary forces in society” looking to make political capital from them, cannot be ignored, Brown insisted.

He concluded his speech by saying: “That is a warning that we must heed, because one has only to look at football grounds to see how the evils of extreme right-wing groups are being preached to youngsters who seek some diversion from the misery of unemployment.”

It seems her photography is still as relevant today as it was nearly 40 years ago, as the divide between the north and the south, and the rich and the poor grows ever wider in the teeth of austerity.

Tish Murtha – Youth Unemployment

However, her sudden death in 2013, when she suffered a brain aneurysm on the day before her 57th birthday, meant the nation lost one of its most important social documentary photographers of recent history.

It also meant the world was left deprived of a tangible or shareable record of her work, with much of her archive surviving only on negatives that she had lovingly kept until her untimely passing.

But her daughter, Ella, was never going to let the legacy of her beloved “mam”, who she had grown up watching “work magic” developing photos in the spare room of their home that doubled as a darkroom, fade away and she embarked on the journey to scan the entire archive.

“My mam genuinely cared about the people she documented,” Ella says.

“She wanted to try to help in the only way she could – with her camera.

“She found she had a gift and a strong social conscience, and I think as a young woman really thought she could help change things and make people take notice and stimulate discussions on real issues through her photography.

“She worried that the pressures of unemployment were diverse and would always stay with these young people.”

As thousands of unseen images emerged, Ella promised to realise Murtha’s dream of creating a book and launched a Kickstarter campaign to make this goal a reality.

It hit its target of £8,000 in just 10-and-a-half hours and the book is expected to be due for release at the end of October.

“My mam was a genius with a camera and the Youth Unemployment book will be an important addition to the history of British documentary photography,” Ella says.

“That is my gift to my mam, to secure her place in photographic history and have her work published. She deserves it.”

origin at… http://www.independent.co.uk

Emily Goddard