An Animal Rights Article from All-Creatures.org

Randy Shields, The Greanville Post

February 2017

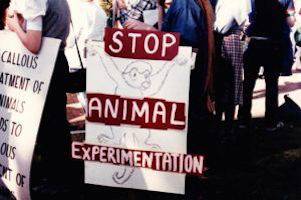

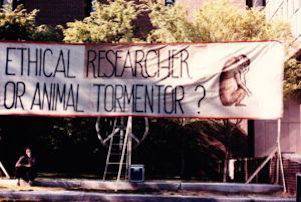

I first met animal rights philosopher Tom Regan in April of 1985 after he’d given a rousing speech in Philadelphia condemning the University of Pennsylvania’s baboon head-bashing experiments. (This was the infamous Thomas Gennarelli lab which the Animal Liberation Front exposed by breaking in and taking tapes the researchers made of themselves.) Tom was walking across the commons area and I asked him to sign a copy of his book All That Dwell Therein: Essays on Animal Rights and Environmental Ethics. The pictures below are of that day.

“To all you good, decent people currently in the vivisection industry, we issue this healing call: Lay down your weapons. Lay down your scalpels and prods. Lay down your Pavlovian slings and restraint chairs. Lay down your stereotaxic devices and your rodent guillotines. Lay down your wires that shock and plates that burn. Lay down your tanks that drown and chambers that deprive. Lay down your sutures that blind and vices that crush. Lay down these weapons of evil and join with us, you scientists who are brave enough and good enough to stand for what is just and true.”

—Tom Regan

These were halcyon times for the animal movement. The annual FARM-organized Action for Life conferences were foundational in networking and training people who had no social change experience. April 24, 1983 marked the official birth of the modern animal rights movement with four Mobilization for Animals rallies in Boston, Atlanta, Davis, California and Madison, Wisconsin. The many thousands who participated went back to our communities, organized grassroots groups and began putting slaughterhouses, research labs and factory farms in the faces of the American public.

In England, the Animal Liberation Front waged war on fur farms, fur stores, factory farms, laboratories and meat shops. In popular culture, the television show LA Law showed graphic footage of animals caught in leghold traps to millions of viewers as part of one episode’s court case — and there were prominent anti-vivisection messages in three 1982 films: The Dark Crystal, The Secret of NIMH and ET The Extra Terrestrial. We were vilified on most meat and pharma-supported news shows but homeboy (Dayton) Phil Donahue gave us a fair hearing. On the west coast the Javier Burgos-led SUPPRESS challenged the superstition of vivisection on scientific grounds and regularly fielded thousands of people to march against vivisection at UCLA and USC. Some hunters, vivisectors and animal farmers came in from the cold of killing and became eloquent spokespeople for the animals. Professional organizations like the Animal Legal Defense Fund, Psychologists for the Ethical Treatment of Animals and the Association of Veterinarians for Animal Rights were formed. PETA made animal cruelty the issue instead of sexist divisive tactics. Both Ingrid Newkirk and Marti Kheel — the latter the founder of Feminists for Animal Rights — were inspirations.

Doing much to fan this whirlwind was a former butcher who became a philosopher and teacher, one who wasn’t satisfied with Peter Singer’s (Animal Liberation) utilitarian arguments for protecting non-humans — or humans, either, for that matter. Instead, North Carolina State Professor Tom Regan knew that to make a case for animal rights he first had make a case for human rights. Why should we be protected? What’s special about us? What are the relevant characteristics shared by, say, a rational adult human and a non-rational human infant? What makes humans human? What characteristics cross over to non-human animals?

Tom answered these questions in his seminal 1983 book The Case for Animal Rights by demonstrating that there are no morally relevant differences between us and most other animals. Animals aren’t merely alive like plants but, like us, they have lives. Beings should have rights even if they are incapable of having responsibilities or rationality. Besides sentience, all creatures possess inherent value — that is, our lives matter to us even if they don’t matter to anyone else. And more importantly, both human and non-human beings are subjects-of-a-life: “Subjects-of-a-life are characterized by a set of features including having beliefs, desires, memory, feelings, self-consciousness, an emotional life, a sense of their own future, an ability to initiate action to pursue their goals, and an existence that is logically independent of being useful to anyone else’s interests.” To think it’s acceptable to do things to non-humans that we would call atrocities if done to ourselves is nothing but pure bigotry and unthinking prejudice, no more legitimate than “might makes right.” Anyone who reads this intellectually rigorous and revolutionary book understands immediately that it demands the complete re-ordering of society, starting with the dinner table. It’s hard-headed, erudite, logical and unassailable. In Tom’s words, this is what it felt like after writing the book — and, I might add, what it felt like for me after finishing it:

“What was perhaps the most remarkable part of working on The Case was how I was led by the force of reasons I had never before considered, to embrace positions I had never before accepted, including the abolitionist one. The power of ideas, not my own will, was in control, it seemed to me. I genuinely felt as if a part of Truth was being revealed to me. I do not want to claim that anything like this really happened. Here I am only describing how I experienced things. And how I experienced them, especially toward the end of the composition of the book, was qualitatively unlike anything else I have ever experienced. It was intoxicating. It was as close to anything like a sustained religious or spiritual revelation as I have ever experienced.” I closed the book and thought to myself: “This is the way, this is the future. This is what rights and laws — and everything that follows — will be based on.”

Whenever Tom saw that the movement lacked something he set about providing it. He felt that organized religion was “spiritually flabby” and “weak from disuse” in its neglect of non-humans and their proper treatment. So one of the three films that he wrote, produced and directed was “We Are All Noah” which featured leaders of various faiths and their perspectives on the treatment of animals. (I often used this non-graphic film — and Silver Medal winner at the 1986 International Film Festival of New York — in presentations to schools and community groups.) Tom edited three books with the Rev. Andrew Linzey on religion and animals and also organized and chaired a conference on religion and science which resulted in the 1986 book Animal Sacrifices: Religious Perspectives on the Use of Animals in Science. I might as well mention his documentary about pioneering older animal activists, Voices I Have Heard, winner of the Gold Medal at the 1988 Houston International Film Festival.

Tom understood that animal exploiters can’t compete on the cultural playing field because there is nothing uplifting about hunting, trapping, vivisecting and slaughtering animals for food — so the pro-animal position has the field all to itself in poetry, dance, theater, film and art to make our case. Accordingly, Tom and his wife Nancy created the annual International Compassionate Living Festival in Raleigh which drew together artists, musicians, theater troupes and writers for several days every October. This led to the formation of the Culture and Animals Foundation which gives grants to people for “exploring the human-animal relationship through scholarship, creativity and performance.”

Like hundreds of other activists I brought Tom to my home town in Ohio to speak and give press interviews. He was indefatigable, upbeat, patient, wise. He saw the horrors of what humans do to other animals but he never let the horror make him bitter or cynical or divert him from his mission of combatting it. He was dynamic and gregarious, a freely-drinking Irishman who was the life of any party whether it was in the Regan home or marching in the streets with a picket sign or even a historic sit-in with 100 other activists at the National Institutes of Health which resulted in funding being cut off to Gennarelli’s monkey-bashing experiments. It’s also impossible to talk about the greatness of Tom without also talking about the greatness of Nancy — the Culture and Animals Foundation was her idea. They were an incredible team and they showed how much can be accomplished by the power of love and the power of two people who love each other.

Tom’s life was filled with interviews, debates, camaraderie, strategizing, conferences, protests and hundreds of lectures here and abroad, including China, Turkey, Italy and the Netherlands. He also excelled at the thankless task of mediating between squabbling individuals and groups within the animal movement. He felt that grassroots activists were as important as movement “leaders” because we were the only ones who could exercise a corrective effect on national groups which were businesses always in danger of getting too comfy with donor money and selling short the animals. Before Tom, there were only a handful of philosophy courses in America that mentioned animal rights — now over 100,000 students each year are discussing the issue. As he said: “It is no exaggeration to say that, during the past thirty years, philosophers have written vastly more on the topic of ethics and animals than our predecessors had written in the previous three thousand.” He wrote over twenty books, most of them concerning animals but also including fiction and scholarly works on the philosopher G.E. Moore. He won the highest teaching award at NC State and also gave what is considered the greatest animal rights speech ever in Los Angeles in 1988. Countless times over the years I would discover that some publication or some pro-animal production was funded by the Culture and Animals Foundation or I would meet someone who wrote something that Tom had edited and critiqued. Or someone who would first discover, say, the work of artist Sue Coe or performance artist Rachel Rosenthal because Tom brought these great people to Raleigh to display their talent.

One of the greatest things that Tom did was to establish the Tom Regan Animal Rights Archive at North Carolina State which contain not only his work but entire collections of other groups and individuals. One such collection is Argus Archives, established in 1969 by the pioneering psychiatrist turned animal activist Dallas Pratt, who disseminated information in the 1960s about the plight of animals in slaughterhouses and research labs. The Regan archives also contain the indispensable work of photo-journalist Ron Scott who seemed to be at every protest and conference documenting the early years of the animal rights movement.

Six years ago, traveling back to Philadelphia from Florida, I got it in my head to call up the Regans even though we hadn’t spoken in many years. They said come on over. I was with my friend Lisa Levinson (of toad detour fame) and we spent several hours visiting. The fact that we were there was utterly Reganesque: Lisa attended one of Tom’s gatherings in Raleigh many years before where she met fellow Philadelphians Jim Harris and Zipora Schultz. They didn’t know each other even though they lived in the same city at the time. They had to make the pilgrimage to Raleigh to find one another — and the three went on to found the cultural animal advocacy group Public Eye: Artists for Animals. That’s what Tom and Nancy did: they were movement builders and change agents, they made it possible for more people to help more animals. They made people stronger. They enriched thousands of lives.

We talked about everything. I asked if he thought there had ever been a credible intellectual challenge to The Case for Animal Rights and he said no but that he felt that the thorniest issue was what to do, if anything, with invasive species. Tom decided that my “mission” was to “call back” all the great activists of the old days who had dropped out of the movement. I didn’t want to be too negative — because Tom is one third of my Holy Trinity, along with Karl Marx and Dr. John McDougall — but I said that, in my own case, I felt like I didn’t know how to be effective any more, that the things we were doing were not working and that the really big gains could only be made once capitalism is overthrown. The animal movement couldn’t keep up with the depredations of global capitalism. Animal liberation can’t precede socialism. (Before we get to Tom’s world, we have to pass through Karl’s world.) Tom disagreed. He felt if enough consciousness was raised and laws were changed, animal rights could happen under any system.

As the conversation wandered up to midnight we talked about those parties at the Regan’s house twenty five years earlier. During the annual festival for the animals, out of town activists would sometimes bunk at the Regan’s (or their equally gracious next door neighbors) and find ourselves in the kitchen cutting up vegetables for the large nightly meals. Tom asked me if I remembered the words of some intolerant judgmental activist back then who excoriated another person who still drank cow’s milk. I racked my brain trying to think who this was — Gary Francione, Carol Michael-Wade, Shelly Shapiro… who? I gave up and asked “So, who said that?” And Tom and Nancy roared in unison: “You did!” “I said that?” Oh, right, right… The Regans were charming, gracious, supportive, always concerned, always interested. Two of the most sterling humans I’ve ever known.

Tom and Nancy were married for 50 years and she and their two children, Karen and Bryan, were with him when he died on February 17. He was 78 years old. They have four grandchildren. Tom always said that the animal rights movement was made up of “many hands on many oars.” But nobody rowed more effectively, tirelessly, more collegially and congenially than Tom. Tom and Nancy, thanks for everything, thanks for making my life better. You two had a big life and you did it right. Tom, for me, you’re going to be forever waving hello. You have the last word:

“My fate, one might say, is to help others see animals in a different way — as creatures who do not belong in cages. Or in leghold traps. Or in skillets. Perhaps, indeed, there is in everyone a natural longing to help free animals from the hands of their oppressors — a longing only waiting for the right opportunity to assert itself. I like to think in these terms when I meet people who are not yet active in the Animal Rights Movement. Like Socrates I see my role in these encounters as being that of the midwife, there to help the birth of an idea already alive, just waiting to be delivered.”

Emotionalism aside, it has been shown that vivisection on animals is not anywhere near the necessity it is claimed to be in the training of physicians or the study of new cures. A variety (and growing field) of alternative methods yield far more reliable conclusions and paths, and clinical study on humans, supposedly the ultimate beneficiaries of all this research, as the fast track research on AIDS proved, is also far more accurate and decisive.

Randy Shields can be reached at [email protected]. His writings and art are collected at RandyShields.com.

SPECIESISM, DOMINIONISM AND THE LAST FRONTIER OF SOCIAL JUSTICE

by Tom Regan

From Resurgence Magazine

Commissioned by Heidi Stephenson

To outsiders, animal rights advocates look like a strange lot. We don’t eat meat, avoid cosmetics tested on animals, and boycott performing animal acts. Drape ourselves in fur? Forget it. ARAs don’t even wear leather or wool. Many people view ARAs as certifiable, grade-A, top of the class nut cases. Reduced to its essentials, however, what we believe is just plain common sense.

What ARAs Believe

We believe the animals killed for food, trapped for fur, used in laboratories, or trained to jump through hoops are unique somebodies – not generic somethings. We believe that what happens to them matters to them. Why? Because what happens to them makes a difference to the quality and duration of their lives.

In these respects, ARAs believe that humans and these animals are the same, are equal. And so it is that all ARAs share a common moral outlook: We should not do to them what we would not have done to us. Not eat them. Not wear them. Not experiment on them. Not make them jump through hoops. “Not larger cages,” we say, “empty cages.”

The Spectre of Speciesism

The argument for animal rights just sketched implies that humans and other animals are equal in morally relevant respects. Some philosophers, Carl Cohen principal among them, repudiate any form of species egalitarianism. According to Cohen, whereas humans are equal in morally relevant respects, regardless of our race, gender or ethnicity, humans and other animals are not morally equal in any respect, not even when it comes to suffering.

Here are a few examples that will clarify his position. First, imagine that a boy and girl suffer equally. If someone assigns greater moral weight to the boy’s suffering because he is a white male from Ireland, and less moral weight to the girl’s suffering because she is a black female from Kenya, Cohen would protest—and rightly so. Human racial, gender and ethnic differences are not morally relevant differences.

According to Cohen, however, the situation differs when it comes to differences in species. Imagine that a cat and dog both suffer as much as the boy and girl. For Cohen, there is nothing morally prejudicial, nothing morally arbitrary in assigning greater importance to the suffering of the children, because they are human, than to the equal suffering of the animals, because they are not.

Proponents of animal rights deny this. We believe that views like Cohen’s reflect a moral prejudice against animals that is fully analogous to more familiar moral prejudices, like sexism and racism. We call this prejudice “Speciesism.” (An important term first coined by Richard Ryder in his book Victims of Science.)

For his part, Cohen takes pride in being a speciesist but denies it is a prejudice. Human suffering, he writes, does “somehow” count for more than the equal suffering of animal suffering. Why? Because (he thinks) while there are no morally relevant differences between human men and women, or between whites and blacks, “the morally relevant differences [between humans and other animals] are enormous.” In particular, human beings but not other animals are “morally autonomous;” we can, but they cannot, make moral choices for which we are morally responsible.

Why Speciesism is a Prejudice

Cohen’s defense of speciesism is no defense at all. Not only does he conveniently overlook the fact that a very large percentage of the human population (pre-verbal infants and young children, for example) are not morally autonomous; moral autonomy is not relevant to the issues at hand. An example will help explain why. Imagine someone says that Jack is smarter than Jill because Jack lives in Syracuse, Jill in San Francisco. Where the two live is different, certainly; and where different people live is sometimes a relevant consideration (for example, when a census is taken or taxes are levied). But everyone will recognize that where Jack and Jill live has no logical bearing on whether Jack is smarter.

The same is no less true when a speciesist says (using two important characters from The Wizard of Oz) that Toto’s suffering counts for less than the equal suffering of Dorothy because Dorothy, but not Toto, is morally autonomous. “Does Toto’s pain count as much as Dorothy’s?” We are given no relevant reason for thinking one way or another if we are told that Dorothy is morally autonomous, Toto not. This is not because the capacity for moral autonomy is never relevant to our moral thinking about humans and other animals.

Sometimes it is. If Jack and Jill have this capacity, then they (but not Toto) will have an interest in being free to act as their conscience dictates. In this sense, the difference between Jack and Jill, on the one hand, and Toto, on the other, is morally relevant. But just because moral autonomy is morally relevant to the assessment of some cases, it does not follow that it is relevant in all cases. And one case in which it is not relevant is the assessment of pain. Logically, to discount Toto’s pain because Toto is not morally autonomous is fully analogous to discounting Jill’s intelligence because she does not live in Syracuse.

The question, then, is whether any defensible, relevant reason can be offered in support of the speciesist judgment that the moral importance of human and animal pain, equal in other respects, always should be weighted in favour of the human being over the animal being. To this question, neither Cohen nor any other philosopher, to my knowledge, offers a logically relevant answer.

To persist in judging human pains (the same applies to equal pleasures, benefits, harms, and so on) as being more important than the like pains of other animals, because they are human pains, is not rationally defensible. Speciesism is a moral prejudice. Contrary to Cohen’s assurances to the contrary, it is wrong, not right.

Dominionism

People sometimes attempt to defend speciesism by appealing to the dominion God gave to humans. The oft-recited passage from Genesis 1.26 (English Standard Version) reads:

Then God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.”

What could be clearer than that the Bible teaches human superiority over other species, from which it follows (speciesists like Cohen will contend) that we do nothing wrong when we turn animals into food, or clothes, or performers. After all, it’s not as if animals are given dominion over humans.

Yes, but. . . . we need to remember that the Bible also teaches that God has dominion over us, and though God could use divine power to exploit us to divine ends, that’s not what the Bible teaches, especially in the books of the new testament. Rather than God exploiting humans, for divine glory, God sacrifices God’s own son for humans.

Note as well that, in Genesis, God grants humans dominion after the fall—after Adam and Eve commit the original sin. Before the fall–before they disappoint God’s hopes as the jewels in the crown of creation–the circumstances are quite different. Recall the relevant passage (Genesis, 1:29):

And God said, “Behold, I have given you every plant yielding seed that is on the face of all the earth, and every tree with seed in its fruit. You shall have them for food. Original Diet – outlined at Creation,

In other words, before the fall, while they lived in paradise, Adam and Eve were vegans. They did not eat animal flesh or animal products. Indeed, they did not wear animal skin or fur. Adam and Eve: the original ARAs.

For those of a certain religious inclination, then, God’s hope in creating the world included peaceful relations between humans and other animals, as exemplified in the Garden of Eden. ARAs who have this same inclination see themselves–in their everyday decisions, concerning what they eat and wear, for example–as taking small but meaningful steps on their journey back to Eden—back to the inter-species peaceful world God created in the first place.

“Humane treatment” is the law

Comparatively speaking, few people are Animal Rights Advocates. Why? Part of the answer concerns our disparate beliefs about how often animals are treated badly. ARAs believe this is a tragedy of incalculable proportions. Non-ARAs tend to believe mistreatment occurs hardly at all. That non-ARAs think this way seems eminently reasonable. After all, we have laws governing how animals may be treated and a cadre of government inspectors who make sure these laws are obeyed. Right?

And what do our laws require? In the language of America’s Animal Welfare Act, animals must receive “humane care and treatment.” In other words, animals must be treated with sympathy and kindness, with mercy and compassion, the very meaning of the word ‘humane’. It says so in any standard dictionary.

If things were as bad as ARAs say they are, there should be an enormous amount of inhumane treatment brought to light by government inspectors. Yet this is precisely what government inspectors do not find. For fiscal year 2009, the Animal Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) conducted 11,179 compliance inspections. Of that total, only 43 sites received formal complaints that were sent to the Administrative Law Court. An apparent compliance rate of over 99%.

No wonder the general public believes that, with rare exceptions, animals are treated with mercy and kindness, with sympathy and compassion.

The myth of “humane care and treatment”

Tragically, the public’s trust in the adequacy of government inspections is misplaced. What APHIS inspectors count as ‘humane’ undermines the inspections before they are conducted. Consider some examples of what happens to animals in research laboratories:

- Cats, dogs, nonhuman primates, and other animals are drowned, suffocated, and starved to death.

- They are burned, subjected to radiation, and used as “guinea pigs” in military research.

- Their eyes are surgically removed and their hearing is destroyed.

- They have their limbs severed and organs crushed.

- Invasive means are used to give them heart attacks, ulcers, and seizures.

- They are deprived of sleep, subjected to electric shock, and exposed to extremes of heat and cold.

Every one of these procedures and outcomes complies with the Animal Welfare Act. Each conforms with what APHIS inspectors count as “humane care and treatment.”

It only gets worse

Per annum, the number of animals used in research laboratories subject to APHIS inspections is estimated to be twenty million. This figure, though large, is dwarfed by the ten billion animals annually slaughtered to be eaten, just in the United States alone.

Remarkably, farmed animals are explicitly excluded from the legal protection provided by the Animal Welfare Act. Here is what the AWA says:

“The term ‘animal’. . . excludes horses not used for research purposes and other farm animals, such as, but not limited to, livestock or poultry, used or intended for food or fiber . . .”

Moreover, after due-diligence hearings and debate, the United States Congress, in 2002, voted to continue to exclude birds, rats and mice from AWA protection too.

But if not our government, who decides what humane care and treatment means for farmed animals, for example? In the real-politik of American animal agriculture, it’s the farmed animal industries who get to write the rules. And what treatment might those rules allow? Here are some examples:

- “Veal” calves spend their entire lives individually confined to narrow stalls too narrow for them to turn around in.

- Laying hens live a year or more in cages the size of a filing drawer, seven or more per cage, after which they are routinely starved for two weeks to encourage another laying cycle.

- Sows are housed for four or five years in individual barred enclosures (“gestation stalls”), barely wider than their bodies, where they are forced to birth litter after litter.

- Until the “Mad Cow” scare, beef and dairy cattle too weak to stand (known as “downers”) were dragged or pushed to their slaughter.

- Geese and ducks are force-fed the human equivalent of thirty pounds of food per day to enlarge their livers, the better to meet the demand for foie gras.

All these conditions and procedures demonstrate the relevant industry’s commitment to mercy and kindness, compassion and sympathy.

Don’t forget the fibre

In the newspeak of the Animal Welfare Act, not just “food” animals fail to qualify as “animals.” The same is true of any whatcha-ma-call-it (aka animals) used for fibre. For leather, for example. Or wool. Or fur.

This is fact, not fiction.

Fur bearing animals, whether trapped in the wild or raised on fur farms, are exempt from the legal protection, scant though it is, provided by the AWA. As is true of animal agriculture, the fur industry gets to set its own rules and regulations of “humane care.”

And what might “humane” fur farming or trapping permit? Here are some examples.

- On fur farms, mink, chinchilla, raccoon, lynx, foxes and other fur bearing animals are confined in wire-mesh cages for the duration of their lives.

- Waking hours are spent pacing back and forth, or rolling their heads, or jumping up the sides of their cages, or mutilating themselves, or cannibalizing their cage mates.

- Death is caused by breaking their necks, or by asphyxiation (using carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide), or by shoving electric rods up their anus to “fry” them from the inside out. (Anal electrocution.)

- Animals trapped in the wild take, on average, fifteen hours to die. Trapped fur-bearers frequently chew themselves apart in a futile attempt to save their lives.

All perfectly legal; every bit of it in keeping with industry standards for kindness and mercy, sympathy and compassion.

Time to get mad

Those of us of a certain age remember the immortal words of the television presenter Howard Beale, in the film Network. “Things are crazy,” says Beale. “The world is a mess. People need to get mad. Real mad. I want all of you to get up out of your chairs,” he says to his viewers, “go to the window, open it, stick your head out, and yell, ‘I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!’”

People who trust what industry spokespersons and government inspectors tell them about the “humane care and treatment” of animals need to follow Howard Beale’s admonition. They need to get mad as hell, and this, for two reasons. Firstly, because of how they have been abused. The plain fact is, they haven’t been told the truth. Instead, they’ve been misled and manipulated by industry and government spokespersons. “Trust us: All is well at the lab, on the farm, in the wild. Animals are being treated humanely.” Secondly, people need to get mad as hell because of how animals are being abused. When the organs of animals are crushed and their limbs severed; when they are made sick by the food they are forced to eat and spend their entire lives alone, in isolation; when they are gassed to death or have their necks broken: no propaganda machine in the world can turn these appalling facts into something they are not.

If the day finally comes when the general public does get mad as hell, the ranks of animal rights advocates will grow in unprecedented numbers. When that day comes – but not until it does – our shared hope for a world in which animals are truly treated humanely will finally have some realistic legs to stand on.

The Last Frontier of Social Justice

In the spirit of Howard Beale, ARAs call upon humans everywhere to understand where we are coming from. We are abolitionists, not reformists. We want to end humanity’s exploitation of other animals, not make it ‘nicer.’ Why? Because we believe that the recognition of animal rights represents the last frontier of social justice.

Those who opposed human slavery were not reformers either. They were abolitionists. They fought to end slavery, completely. Those who worked for (and continue to work for) women’s rights and the rights of gays and lesbians are not reformers. They are abolitionists too. They fought (and continue to fight) for an end to all forms of discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation, completely.

ARAs invite others to join us on this last frontier of social justice. Human exploitation of other animals is rooted in deep, speciesist prejudice. There is no getting around that fact. Because speciesism is indefensible, this exploitation is indefensible too. When the dust of debate settles, there is only one adequate response: to abolish the tyranny we exercise over other animals. Completely.

Tom Regan is emeritus professor of philosophy at North Carolina State University. Identified as “the philosophical leader of the animal rights movement,” the editors of Utne Reader also named him, along with the Dali Lama, as one of “fifty visionaries who are changing the world.” His many books include: Empty Cages: Facing the Challenge of Animal Rights, The Case For Animal Rights and Animal Rights: Human Wrongs: An Introduction To Moral Philosophy.

The late Tom Regan was emeritus professor of philosophy at North Carolina State University. Identified as “the philosophical leader of the animal rights movement,” his many books include: Empty Cages: Facing the Challenge of Animal Rights; The Case For Animal Rights and Animal Rights: Human Wrongs: An Introduction To Moral Philosophy.

May the man who put so many on the Good path inspire a whole new generation now in his passing. We all need a dose of Tom Regan thinking and feeling. The suffering animals have just lost their greatest advocate. This is a recruitment call!

Comment by Heidi Stephenson on 2 March, 2017 at 8:07 am