‘In this sacred grove there grew a certain tree round which at any time of the day, and probably far into the night, a grim figure might be seen to prowl. In his hand he carried a drawn sword, and he kept peering warily about him as if at every instant he expected to be set upon by an enemy. He was a priest and a murderer; and the man for whom he looked was sooner or later to murder him and hold the priesthood in his stead. Such was the rule of the sanctuary.’ JG Frazer ‘The Golden Bough’ 1890.

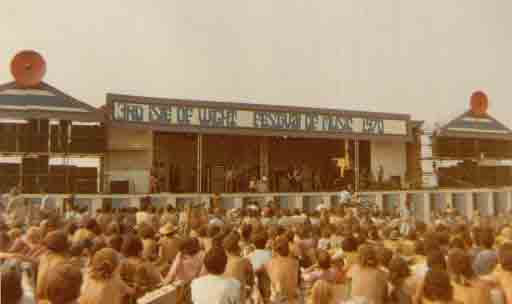

The British hippy festival summer of 1970 concluded on the Isle of Wight in at the end of August, with not very clearly defined battlelines drawn up between the hippy elite and the outsider freaks. Due to a dispute over ticket prices, the hill overlooking the official site became the Notting Hill-by-sea alternative festival venue ‘Desolation Row’, subject to constant Hawkwind and Pink Fairies ‘Pinkwind’ appearances. On the inside the bill featured Jimi Hendrix, the Who, the Doors doing ‘The End’, Jethro Tull, Free, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and Supertramp (whose commune was, appropriately enough, in the Holland Park area). As Friends, IT and Oz combined to cover the festival as the Freek Isle of Wight newsletter, Mick Farren became the hippy Napoleon of Notting Hill, leading the field hippy revolt out of style, he claims unintentionally, in which the festival fences were stormed by the White Panthers, hell’s angels and French anarchists

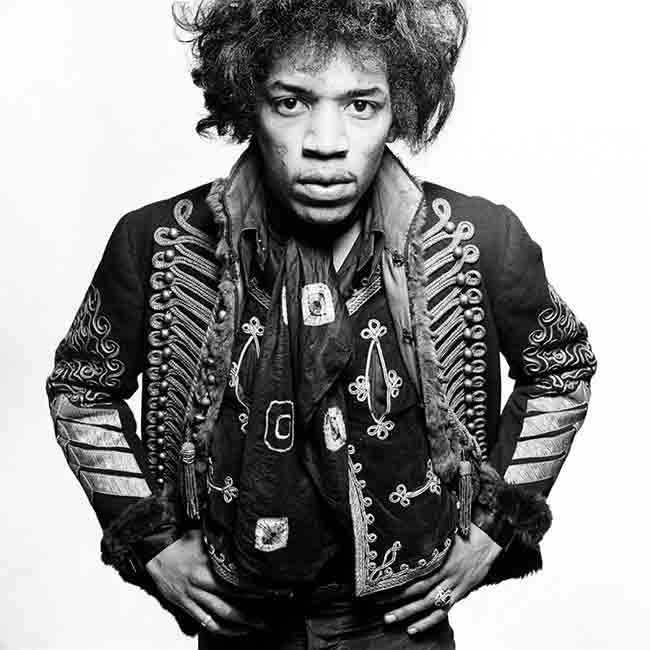

Into the British acid rock apocalypse flew Jimi Hendrix, to give by all accounts a lacklustre performance. Mick Farren thought he was acting like ‘a man on a mission without a map’; Charles Shaar Murray called his set a virtual suicide note. Hawkwind remember him being too depressed to jam on ‘Desolation Row’, but they claim he agreed to play at Stonehenge with them. Alan Dearling recalls: ‘I was at the Isle of Wight 1969 and 1970 festivals. My experiences of what happened are different than Farren’s account which always focused on the ‘bit’ he says took place. Everyone’s experiences are unique. The pitched battles over the fences around the festival were mostly because there were fences. It became more aggressive as the security and stage announcements fanned the flames. The sound from the single mainstage was dodgy, but better up the hill – where seating was free. Hendrix did look uncomfortable with this band, but he also performed well on new tracks like ‘Machine Gun’. It wasn’t his best show and the audience was talking mostly about whether he and Miles would perform together. That didn’t happen. This was also the last UK showing for Jim Morrison and the Doors. His set was dark and of a high calibre, but he was now a great bear of a man, not the leonine poet of earlier days.

After the Isle of Wight riot, Hendrix’s final Band of Gypsies tour ended at an even more apocalyptic sounding festival in Germany where hell’s angels burnt down the stage. Back in London, he had a series of meetings with Alan Douglas (who had just released the Last Poets album in the run up to the delayed opening of ‘Performance’) and his original manager, the former Animal Chas Chandler, as he attempted to extricate himself from his deal with Mike Jeffrey. Hendrix seems to have mostly stayed in South Kensington with his American super-groupie girlfriends, Alvenia Bridges and Devon Wilson. But, as Jerry Hopkins summed up the Jimi Hendrix Experience, ‘in the final weeks of his life Jimi slept in many beds.’

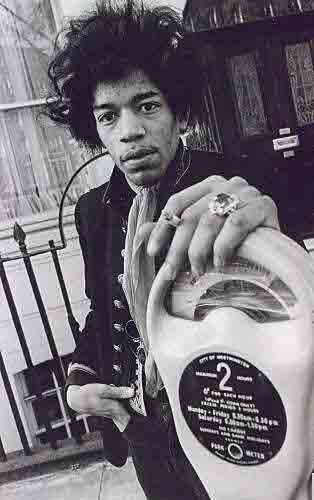

In the News of the World’s investigation into ‘Jimi’s last lost days’, he came to Notting Hill and ‘smoked pot at various pads.’ Jerry Hopkins has him ‘on a roll, careening from flat to flat, club to club’. Another girlfriend, Lorraine James told the News of the World, “Jimi was completely out of his mind.” In the psychedelic madness at one Notting Hill pad they visited, she recalled a man jumping over the banisters and breaking his legs: “When all this was happening Jimi went mad and ran around the house shouting.” He was quoted as saying, “I need help bad, man.” Robin McKidd, a multi-instrumentalist who played with Lindisfarne and the Strawbs, recalled driving into Notting Hill one morning when ‘all of a sudden this completely wasted dude comes out of nowhere and lands on the bonnet of his car’; the person who he recognised as Hendrix stumbled off refusing his offers of help.

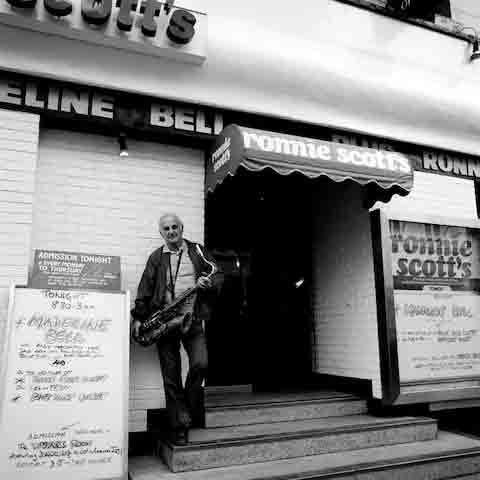

On September 17/18, the day after Hendrix’s last gig at Ronnie Scott’s with War (the new group of the other former Animal Eric Burdon), he went to Kensington Market on the High Street (where Freddie Mercury of Queen was a stallholder at the time) and a party thrown by Mike Nesmith of the Monkees. After that he returned to Notting Hill for the last time, with his German iceskater girlfriend Monika Dannemann. He was reputedly last seen in Roy Stewart’s Globe bar at 103 Talbot Road off Powis Square and/or the Mangrove restaurant at 8 All Saints Road. On the morning of September 18 1970, Jimi Hendrix ended up on Ladbroke Grove in the basement of 22 Lansdowne Crescent, then called the Samarkand Hotel after the Silk Road staging post in Uzbekistan. Lansdowne Crescent is at the epicentre of the upper-class Ladbroke Estate, on the summit of the Notting Hill knoll and the probable site of a Roman villa.

Having taken barbiturates earlier, Hendrix polished off a bottle of sleeping pills and was sick in his sleep. When Monika Dannemann realised something was wrong she apparently called round various rock personalities, and buried her dope in the garden, before calling an ambulance. According to the police report, he was alive when the ambulance arrived at Lansdowne Crescent but DOA at St Mary Abbot’s hospital in South Kensington. Cause of death was ‘inhalation of vomit due to barbiturate intoxication’, later changed to an open verdict; probably a pharmaceutical miscalculation, rather than a deliberate overdose. Monika Dannemann claimed that she lived with Hendrix in the rented flat for 3 weeks, talking about life, the universe and everything. According to everyone else, he hardly stayed there at all.

With his hectic sex and drugs and rock’n’roll lifestyle, Hendrix couldn’t have spent more than a few weeks in Notting Hill all told, and probably didn’t die here but in the crosstown traffic south of Notting Hill Gate. Yet his local pop cultural legacy is second to none; apart from maybe Bob Marley, who also spent more time in the south of the borough. Other local Hendrix sites include the ‘Purple Haze’ house, 167 Westbourne Grove; another girlfriend/dealer’s pad on Ladbroke Grove between Cambridge and Oxford Gardens; and the pop art gallery at 110 Golborne Road, on the Portobello crossroads, formerly the Japanese Asahi shop who in 2004 were attempting to sell a sofa they claimed belonged to him.

In ‘Once Upon a Time there was a Place Called Notting Hill Gate’, the Wise brothers noted: ‘One truly sad incident vis-à-vis the dayglo desperate life of rebel stars. It was on All Saints that Jimi Hendrix – perhaps the greatest jazz-rock guitarist of all – on the eve of music entering into total eclipse, either ODed or committed suicide, leaving behind his dying-to-be-loved, final farewell on a piece of paper’ – possibly referring to his last Ladbroke Grove poem. Before Hendrix’s residency, Lansdowne Crescent had hosted an office of the black underground paper Hustler in 1968, the Howard Marks associate IT editor Graham Plinston, and the ’68 student leaders Dany Cohn-Bendit and Rudy Dutschke.

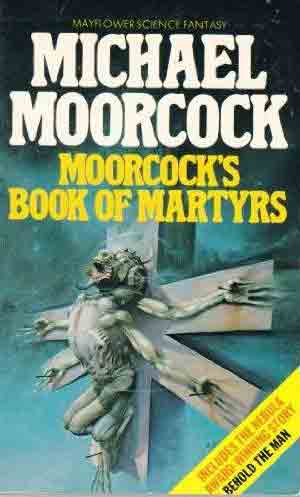

‘The chick began to run after the black truck as it started up and rolled a little way before it had to stop on the red light at the Ladbroke Grove intersection. “Wait”, she shouted. “Jimi!” But the camper was moving before she could reach it. She saw it heading north towards Kilburn. She wiped the clammy sweat from her face. She must be freaking. She hoped when she got back to the basement flat that there wouldn’t really be a dead guy there. She didn’t need it.’ Michael Moorcock, ‘A Dead Singer’ (in memory, among others, of Smiling Mike and John the Bog) ‘Moorcock’s Book of Martyrs’ 1974.

While he was still alive Hendrix was represented in ‘Performance’ as Mick Jagger’s Powis Square basement lodger ‘Noel’ and in poster form. After fulfilling his “once you’re dead you’re made for life” prediction, he was resurrected by the sci-fantasy author Michael Moorcock, or his ghost haunts the street hippies of the Grove underground scene in the 1974 shortstory ‘A Dead Singer’ in ‘Moorcock’s Book of Martyrs’. ‘Shakey Mo’, the Deep Fix roadie from his Jerry Cornelius time travel novels, had spent too long in Finch’s, the Duke of Wellington at 179 Portobello Road, suffering from severe acid-rock withdrawal symptoms, and become Hendrix’s roadie on the astral plane. On a final Portobello stop-off, after visiting the Mountain Grill cafe at 275, Mo scores Mandies (Mandrax) on Lancaster Road and gets into a fight in Finch’s, before his last gig DJing at an astral-rock party in an Oxford Gardens basement pad.

“Hi”, said the newcomer. “I’m looking for Shakey Mo. We ought to be going.” The black man stepped across the others and knelt beside Mo, feeling his heart, taking his pulse. The chick stared stupidly at him. “Is he alright?” “He’s Oded”, the newcomer said quietly, “he’s gone, d’you want to get a doctor or something, honey?” “Oh, Jesus”, she said. The black man got up and walked to the door. “Hey”, she said, “you look just like Jimi Hendrix, you know that?” “Sure.” “You can’t be – you’re not are you? I mean, Jimi’s dead.” Jimi shook his head and smiled his old smile. “Shit, lady. They can’t kill Jimi.” He laughed as he left.’

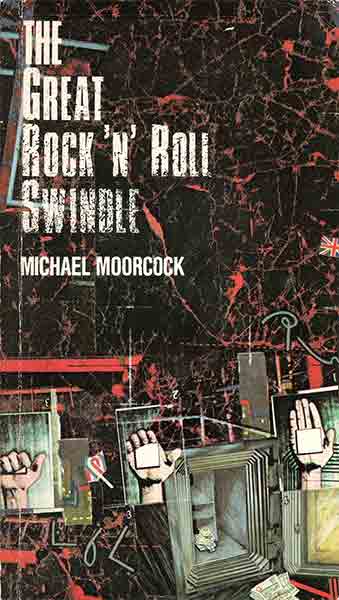

In Michael Moorcock’s 1980 novelisation of ‘The Great Rock’n’Roll Swindle’ Sex Pistols film, Jimi, Marc Bolan and Sid Vicious follow events from the celestial Cafe Hendrix. In rock reality, the Hendrix guitar roadie Gerry Stickells was in a flat on Elgin Crescent when he was called to his last soundcheck at St Mary Abbot’s hospital. Elgin Crescent (the next street but one down the hill from Lansdowne Crescent), of Madame Blavatsky and Nehru previous, acquired a tenuous Janis Joplin connection in 1998 when the ‘Lord Won’t You Buy Me a Mercedes-Benz’ ad featured the bus stop at the Clarendon Road end. In the 90s the Special Photographers’ gallery, off Elgin Crescent on Kensington Park Road, presented a series of dead rock and jazz star exhibitions featuring Hendrix, Janis Joplin, John Lennon, Chet Baker and Sid Vicious.

Before Hendrix, the ‘Telstar’ producer Joe Meek, who was on Lansdowne Road in the late 50s, committed suicide in 1967; and the Hendrix associate Rolling Stone Brian Jones, who was in Powis Square in the early 60s, died of drug-related misadventure in ’69. After the classic ‘king of the hill’ sacrificial demise of Hendrix, a succession of rock martyrs have met the same fate in the Grove or at least had local connections. The enigmatic folk recluse Nick Drake, who recorded at the Island studios on Basing Street, made a legendary last appearance on Cambridge Gardens in 1974 before committing suicide (recounted in Nick Kent’s ‘The Dark Stuff’). The same year, the occult bluesman Graham Bond, who was on Powis Terrace in the 60s, jumped in front of a train after an exorcism at Long John Baldry’s house. Paul Kossoff, the guitarist of Free of ‘All Right Now’ fame who lived in Munro Mews off Golborne Road, ODed in 1976. Free are also worthy of note as the only band that refused to play for nothing at Mick Farren’s Worthing festival.

Marc Bolan, who lived on festival summer of 1970 concluded on the Isle of Wight white, died in a car crash in 1977; Steve Peregrin Took, of drugs misadventure on Cambridge Gardens in 1980; Pete Farndon of the Pretenders ODed on Oxford Gardens in 1983; Sid Vicious worked on a Portobello market stall; Ian Curtis appeared at Acklam Hall with Joy Division; Kurt Cobain of Nirvana visited Rough Trade on Talbot Road and posed outside 19 All Saints Road; Richey Edwards of the Manic Street Preachers was last seen in Bayswater. Michael Moorcock’s Hendrix ghost story is dedicated to the Hawkwind roadie/dealer Smiling Mike, who fell to his death whilst attempting to climb up a drainpipe to the Frendz office on Portobello. Hawkwind also paid their respects to him in ‘Days of the Underground’ on their 1977 album ‘Quark Strangeness and Charm’. The Hendrix super-groupie Devon Wilson died in a mystery plunge from the Chelsea Hotel in New York. His manager Mike Jeffrey perished in a plane crash.

His last girlfriend, Monika Dannemann, committed suicide in 1996 after a quarter of a century legal catfight with his British girlfriend, Kathy Etchingham, who lived with him in the Handel/Hendrix blue plaque house in Mayfair, 23/5 Brook Street W1. Monika Dannemann never left the early 70s; after going out with Uli Roth of the German heavy metal band the Scorpions, she lived out her days as a sad recluse in her Hendrix shrine Sussex home, surrounded by her paintings of him on the astral plane. Whereas ‘Foxy Lady’ inspiration Kathy Etchingham became a respectable doctor’s wife and sold off such sacred rock’n’roll relics as Jimi’s stash box and ashtray at Bonham’s. As Chas Chandler resumed his managerial duties on the Hendrix astral plane tour, in a posthumous All Saints Road link the Hendrix estate refused permission for ‘Electric Ladyland’ material to be used in the All Saints group film ‘Honest’. On the 30th anniversary of Hendrix’s death, Paula Yates, The Tube presenter ex of Bob Geldof, died of drugs misadventure in St Luke’s Mews off All Saints Road.

A fortnight after Hendrix died, the preliminary hearings of the ‘School Kids’ Oz trial began at Marylebone Magistrates Court. The adult Oz editors, Richard Neville, Felix Dennis and Jim Anderson, appeared dressed as school kids for the occasion. The same month Michael X was also committed for trial at the Old Bailey over the Black House ’slave collar affair’. Richard Neville concluded in Oz 31, the ‘End of Era’ issue: ‘The flowerchild that Oz urged readers to plant back in ’67 has grown up into a Weatherwoman (US hippy terrorist); for Timothy Leary, happiness has become a warm gun. Charles Manson soars to the top of the pops and everyone is making war and loving it.’

TOM VAGUE

Fictitious stuff and nonsense!

Comment by Jeff Dexter on 13 September, 2020 at 8:16 amA farrago of nonsense and an insult to the great guitarist’s memory. If you are going to write an account of Jimi’s death, refer to the original sources: his immediate entourage on that sad day, the emergency services who treated him, the doctor who carried out the post mortem, and finally the writers who have taken the trouble to research Jimi’s last days.

Comment by Rollo Treadway on 20 September, 2020 at 8:55 pmonce when I had a one-day-a-week job

Comment by jeff cloves on 8 October, 2020 at 2:38 pmI fell to talking with a young woman part-timer

who also worked there

she was the poshest most cut-glass person I’ve ever met

and the daughter (granddaughter ?) of a once extremely

eminent Tory Cabinet Minister

she had her own estate in Scotland and talked grandly

about ‘my deer’ who roamed there

once in circumstances I can’t recall she told me she’d

once-shared a taxi-cab with Jim Hendrix

‘and you know – he was an absolute pussy cat!’

as Chuck Berry wrote: ‘it goes to show you never can tell’

“What about murder?” she wrote. Several of the more recent Hendrix biographies mention that a liter of red wine was found in his lungs of all places. Nobody does that unless it was poured in my assassins holding him down. Several have accused Mike Jefferey of planning the murder and report he had said Hendrix was worth more dead than alive.

Comment by Norman Gilbert on 16 March, 2021 at 5:31 am