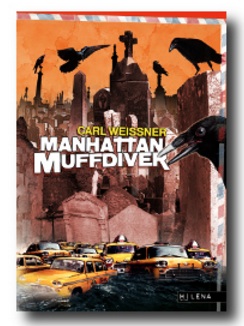

Carl Weissner’s novel Death in Paris — first published online in 2009, then as a paperback in 2012, and finally as an ebook in 2014 — was about a different kind of death from the terrorist assault on Saturday night. Writing in English, his second language, Weissner drew on the trappings of detective fiction and centered the action on a serial killer whose terrorist disposition was entirely private. But Carl was onto Islamist terrorism in Manhattan Muffdiver, published in 2010. Typically, the satirical tone of his “vulgo-cynicism,” as he called it, was black and biting.

Carl Weissner’s novel Death in Paris — first published online in 2009, then as a paperback in 2012, and finally as an ebook in 2014 — was about a different kind of death from the terrorist assault on Saturday night. Writing in English, his second language, Weissner drew on the trappings of detective fiction and centered the action on a serial killer whose terrorist disposition was entirely private. But Carl was onto Islamist terrorism in Manhattan Muffdiver, published in 2010. Typically, the satirical tone of his “vulgo-cynicism,” as he called it, was black and biting.

![Carl Weissner: 'Always These Nightmares . . .' from Manhattan Muffdiver [Milena Verlag, 2010]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Always-These-Nightmares-.-.-.4.jpg)

Postscript: Nov. 16 — I’ve been reminded by Gary Lee-Nova (see his comment) about a terrorist attack described in Death in Paris. (Thanks, Gary.) Please remember, that novel was written half a dozen years ago. The assault it describes is not the one that occurred several days ago, although the number of fatalities it gives — “About 130 of them were dead before they hit the ground” — is remarkably close to the latest figure of 129 dead in the recent attack.

Carl exploited a collage technique of “cut-ups” and “fold-ins” in all his fictional writings. Death in Paris, while not strictly a cut-up text, makes use of the idea as an organizing principle — and it’s worth recalling what William Burroughs, who collaborated with Carl on various cut-up experiments, said about the technique: “When you experiment with cut-ups over a period of time you find that some of the cut and re-arranged texts seem to refer to future events.”

Avenging Ghosts of the Llano Estacado

Most of the 400 people on the square in front of Notre Dame on this Saturday afternoon were tourists strolling around or sitting on the massive stone benches on three sides of the Place du Parvis N.D., eating snacks or aiming their cameras at the cathedral which after extensive sandblasting looked incongruously…new.

The twelve Black Widows in flowing chadors, their faces not veiled, came from three different directions in groups of three and two. Half of them were carrying, in addition to the triple-cascade C4 harness around the midriff, elaborate nail bombs that looked like auxiliary parachutes on their backs.

They converged on the center of the square and formed a circle, holding hands. Almost instantly, they were detonated by radio signal.

The signal came from an old model Motorola C200 cell phone.

The blast ruptured eardrums as far away as the pedestrian crossing on Rue de la Cité and swept about a dozen children and adults down the wide steps leading to the Crypte Archéologique.

Most of the people on the square appeared to get yanked sideways or outward as if on invisible ropes. About 130 of them were dead before they hit the ground.

In the horizontal hail of screws and nails from the bombs, at least fifteen children who had been feeding the birds fluttering above the low privet hedges bordering the square on the side facing the Left Bank were torn to pieces.

A photographer, his face flecked with blood, his hands shaking, took a picture of a kid’s rucksack studded with nails and with the kid’s headless torso still attached to it.

The silence following the blast lasted approximately three seconds; enough for survivors to become aware of a helicopter with a large white cross on its bottom hovering overhead. Somebody, secured by a harness, was leaning out shooting video of the carnage.

After that, panic. A chilling chorus of piercing cries. Chaos.

Half of the large glass front of the Hôtel Dieu entrance (oldest Paris hospital), on the left as you look toward Notre Dame, was shattered. Within sixty seconds of the detonation, doctors, nurses and orderlies with stretchers were rushing out.

A young intern sank to her knees next to a man bleeding from a bad neck wound caused by a flying shard of plate glass. He was alternately gasping and gurgling. Without a second’s hesitation she plucked out the shard and intubated her patient through the open wound.

Hysterical survivors, one of them a cop, were seen stomping upon the severed heads of three of the Widows. Many survivors looked strangely disfigured and leprous. It was the blood and shredded entrails of the victims clinging to their arms and faces.

The wave of the blast entered Notre Dame through the three tall doors which were wide open. Inside, it blew out candles left and right.

There was no visible damage to the famous stained-glass rosetta on the front of the cathedral.

Less than half an hour after the blast, the footage shot from the fake medevac chopper appeared on an Islamist website (“Regard, oh brothers, the glorious battleground…!”) It was copied and uploaded on YouTube and elsewhere dozens of times right away.

On Sunday — inexplicably, since the Place du Parvis Notre Dame and its surroundings were cordoned off — a huge banner was unrolled from the balustrade above the rosetta of the cathedral: PAS DE VIERGES AU PARADIS!

It was considered a particularly heinous outrage in the Muslim world as it seemed to suggest that the twelve martyrs had been lesbians.

There was a mass exodus of tourists from Paris. There was vicious vigilante action against brownskinned persons in various parts of the city. The President, foaming and sputtering, addressed the nation from a secret location underneath a mountain somewhere.

Radio Beur, a Maghreb FM station with studios in the 18th Arrondissement, had gone ballistic with pride and joy. It had received a visit from the Police du Raid which left the equipment in pieces, the owners and staff in the basement of the Préfecture de Police for marathon sessions of torture and interrogation.

Within a day or two, jihadists were broadcasting hate sermons from mobile pirate stations all over town.

Alain Laurin, feeling clipped behind the knees by the Fates, decided to move the Sniper story to Cairo.

As Burroughs said, “The future leaks out.”