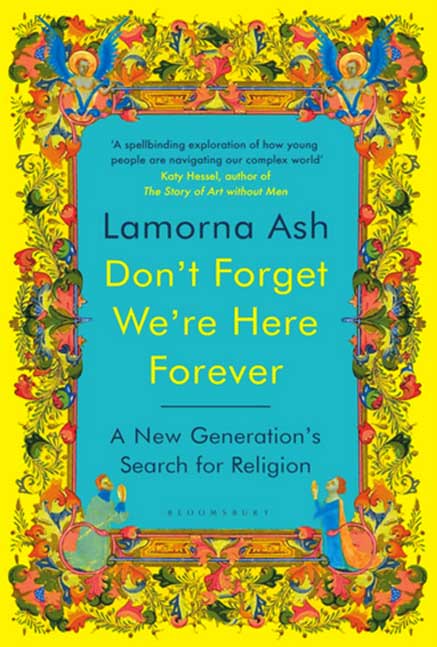

Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever, Lamorna Ash (Bloomsbury)

This isn’t really about ‘A New Generation’s Search for Religion’ – the book’s subtitle, it’s about Lamorna Ash’s search for religion, for life’s meaning and a place that will accept her. She dresses this up as ‘research’, visiting lots of different sorts of churches and going on several retreats, recording conversations and observations, gradually finding people and a couple of places she can relate to.

One of these is a quaker meeting house, the other a welcoming and liberal C of E, both in London where she lives. She welcomes the chance to sit in silence with people at the quakers, and although she sometimes struggles with the lack of contributions (quakers wait until ‘led’ to speak and share something), she also appreciates the fact there is no doctrine or set of rules to follow, and that atheists, agnostics and believers can gather together in a spiritual environment.

Don’t Forget… is a strange read. Although ostensibly about others, the book feels self-obsessed: Ash is always worried about what people will think about her, how she feels, wants to find a place that will not challenge her polysexuality or way of life, wants to find rituals and messages that will educate and inform rather than move or change her. She dips into the Bible and a few mystics’ writings, such as Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love. She also seems to be drawn towards but ultimately sceptical of the mystical, several times reporting how others use the idea of ‘a thin place’ to describe locations (such as Iona) where heaven and earth appear to be closer together.

Thankfully, Ash very quickly decides that she will avoid evangelical, happy-clappy christianity, and is wary of indivduals and churches who evidence censorious and right-wing attitudes and morals, believing they have the right to interfere with others’ lives. I have to be honest and say I’m intrigued and puzzled by the fact that she doesn’t consider any other forms of faith or spirituality in the UK but immediately engages with mostly obvious versions of western christianity, quickly glossing over institutional problems such as abuse, control and sexism. (Although they all get a mention.)

The book is full of stories and conversations with others, yet everything is filtered through the mind of the author, who is desperately trying to make sense of her place in the world. There’s an intellectual and rather British reserve at work here; in no way does Ash wish to be swept up in anything or accept any grand metanarrative that attempts to explain everything. She prefers occasional forays into (sometimes torturous) asides about Marianism, sex and gender roles and ponders the relationship between Jesus and the institutionalised church.

Whilst the last thing in the world I would want to read about is some conversion or magical religious experience, the author’s general reserve and distance is off-putting. There is an over-riding feeling of somebody wanting to make use of something for herself rather than genuinely risking anything. Ash is not in search of religious experience let alone spiritual faith, truth or belief, she is making use of others’ stories and ideas and writing a book about it. It feels like religious tourism to me.

.

Rupert Loydell

.