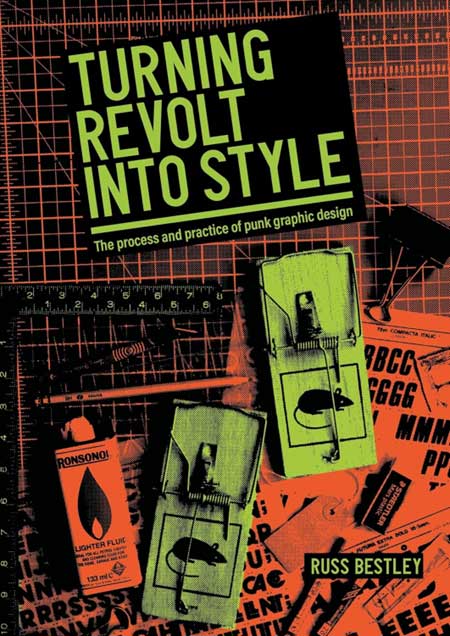

Turning Revolt into Style: The process and practice of punk graphic design, Russ Bestley

(Manchester University Press)

Russ Bestley is someone who knows more – and has written more – over the last thirty years about punk, graphic design, and popular culture than Monsieur Mangetout has had odd dinners. In his latest book – Turning Revolt Into Style – he addresses two key questions: how did a generation of young, punk-inspired graphic designers navigate the profession; and how did significant changes in printing technology, labour relations and working practices in the design profession impact their work?

His aim, therefore, is to situate punk’s visual aesthetic both within cultural history and the technological, professional, and political contexts that materially shaped it. I’m pleased to say that he achieves this, producing a highly useful punk graphic design historiography in the process. Bestley also touches on other ideas which I found just as fascinating and which I would like to briefly comment on here: (i) the deployment of humour within punk; (ii) the privileging of the punk amateur; (iii) punk’s failure.

On the deployment of humour within punk

According to Bestley, those involved in the early punk scene displayed a ‘deep-seated, ironic intelligence’ and possessed a keen sense of the absurd, cheerfully embracing strategies of parody and pastiche just as others working within the ‘long tradition of satirical insurrection’ had done before them.

The Sex Pistols were always more music hall than musical, as became clear in The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle when they openly incited not outrage, but laughter. Sometimes this was mocking and cruel, but it was laughter all the same, and often self-directed as they made themselves ridiculous in the eyes of those who would insist upon punk rock’s moral and political seriousness.

If they began by calling for ‘Anarchy in the UK’, the Sex Pistols ended up advocating for a revolution of fun that was playful, irresponsible, and ridiculous in nature. There are many critics who hate them for this; who dismiss such a concept of fun as lowbrow entertainment and an essentially false form of pleasure, allowing their language to submit, as Barthes would say, to a series of moralising imperatives. This is, of course, merely a form of intellectual snobbery, so I was pleased to see Bestley voice support for fun as a vital component of popular culture and suggest that punk graphic design was largely not so much subversive as ‘simply playful and witty’.

On the privileging of the punk amateur

Sadly, in this professional era, the amateur is often looked down upon. Which is a pity, for the amateur is a virtuous figure; free spirited, open minded, and full of passion for their discipline regardless of whether this brings public recognition or generates an income. Professionals may regard them with a mixture of suspicion and contempt but noble amateurs have often made crucial contributions to science, the arts, sport, and society.

Ultimately, as Roland Barthes notes, the true amateur is not defined by inferior knowledge or an imperfect technique but, rather, by the fact that he does not identify himself to others in order to impress or intimidate; nor constantly worry about status and reputation. Crucially, the amateur unsettles the distinction between work and play, art and life, which is doubtless why they are feared by those who like to police borders, protect categories, and form professional associations.

One of the things I admire about Bestley’s study is that it celebrates this philosophy and often sing the praises not just of up-and-coming designers fresh out of art school or long-established design professionals but visual practitioners who are quite genuinely amateur: ‘The diversity of punk graphic design styles and aesthetics’, he argues, can only be understood in relation to all three groups and a ‘significant part of the emerging punk aesthetic was driven by enthusiastic followers and amateur producers’

However, Bestley is not naïve and he concedes that if, on the one hand, it was ‘the simplicity of the lo-tech, handmade flyers […] along with an underground revolution in homemade fanzines and other printed ephemera produced by inspired and enthusiastic fans […] that kickstarted a punk design aesthetic’, it was, on the other hand, ‘the hugely influential work of professional art directors and designers […] that helped it reach a mainstream audience’.

For me, the main takeaway from Bestley’s book is that amateurs and professionals need one another and that both types of producer ‘informed the wider punk aesthetic and reflected common visual conventions that were emerging as the new subculture made a nationwide impact’. Those who lack education, skills, and material resources but who still attempt to do things for themselves should not be looked down on. But inverted snobbery aimed at those who are professionally trained and talented and do have access to the very latest technologies is also unwarranted. Besides, as Bestley notes, ‘changes in the social and technical practices of design blurred the boundaries between amateur and professional production’, so perhaps this distinction is now redundant.

On punk’s failure

Just as Bestley is honest enough to admit that amateurism will only take you so far, so he concedes that, ultimately, punk was a failed musical revolution that did very little to change the way major record labels operated and that ‘commercially viable areas of punk and new wave were rapidly absorbed, just like the at-the-time radical music and youth scenes that preceded them’.

Similarly, while some of the ‘new breed of punk-inspired graphic designers set themselves apart from the traditional art departments […] many of the more successful practitioners joined the ranks of the commercial studios as time went on’. Thus, by the close of the 1970s – if not sooner – ‘the original punk scene in the United Kingdom had been largely commercialised through the rebranding of new wave and post-punk’.

Whilst that’s true, it’s important to recall that ‘some of the movement’s more successful exponents’ were more than happy to collaborate in this and to assume elevated positions within ‘a revised and updated professional arena’ and build long-term careers – including Johnny Rotten. In other words, there were plenty of ambitious and aspirational individuals who wanted to ‘get ahead’ and had no issue with transforming from outsiders into celebrities and/or young entrepreneurs for whom punk ‘afforded entry to the fields of journalism, popular music, film, photography and design’.

Some may still have pretended they wanted to ‘smash the system’ or ‘disrupt it from the inside’, but we all know most simply wanted to feather their own little nests and, whilst wearing their designer suits, turn rebellion into money. Having said that, however, like Bestley I don’t much care either for those who continued to cling on to a ‘stereotypical model of punk […] despite the proliferation of new styles and the fragmentation of post-punk in myriad new directions’. And, like Bestley, I was less than impressed by hardcore punks in the early 1980s who ‘seem fixated on death, destruction and war, with little of the humour or self-awareness of the previous punk generation’.

Hardcore punk designers were less than imaginative too, giving us endlessly repeated ‘illustrations of stereotypical “punk” figures replete with studded leather jackets and mohican hairstyles’ which helped to establish ‘a set of generic graphic conventions that unfortunately still resonates across global punk scenes today’. Bestley concludes that, unlike the first wave of punk designers, ‘who quickly moved on from what were fast becoming stereotypical visual symbols – such as the swastika, safety pin and razor blade – this punk generation seemed stuck in a time loop (or doom loop) of its own making’.

Away from the hardcore dinosaurs, however, ‘punk and post-punk dress styles shifted […] to the more flamboyant and expressive end of the dressing up box’, as a colourful new romanticism replaced punk nihilism and even McLaren and Westwood moved with the times, transforming Seditionaries into Worlds End. Black bondage trousers were now out and gold striped pirate pants were now in, and the punk revolution had proven to be largely ineffective ‘in its ambition to move away from pop music traditions and long-standing business practices, with many artists […] falling into line as the industry took control’.

Indeed, one is tempted to ask, fifty years after the event, why on earth punk continues to fascinate and why so many ‘punk scholars’ believe it still plays a crucial role as a core element of subcultural identity. Since punk has so clearly and so completely been recuperated ‘through the cementing of a set of visual and musical tropes’, shouldn’t we just stop using the word altogether?

.

Stephen Alexander

.