At the Royal Opera House, London on Saturday 17 January 2026, 1pm

Poets, like dancers, are at one with their surroundings. This is sensitivity, not insanity.

Virginia Woolf is always on stage. She is watching the lives and loves and joys of her characters revealed through intimate duets of impossible beauty. She hears a haunting score while the ocean roars.

The stage is dark and the only setting is three giant picture frames, representing the rooms and pages within which these lives are confined. The frames slowly turn and align. Virginia hides behind them, peering round. For Septimus, the base of one frame becomes the windowsill.

Did Virginia ever watch a ballet at the Royal Opera House? Or an opera, for this ballet is also opera in Act 3? She could not have imagined the music of our greatest living British composer, Max Richter (all love and admiration still to Michael Nyman), who was not yet born in her lifetime. I bought a ticket for the opening performance as soon as the date was released, primarily because I am drawn to anything Wayne choreographs, but equally to sit for three hours inside a Max Richter world.

By the time Virginia published The Waves, the Royal Opera House was either a furniture depositary or dance hall, closed for performance as the tanks rolled west. Virginia had already been moved to Sussex after the bombing of her Bloomsbury home and was denied access to London by her husband and supporting male doctors, in the name of protecting her mental health.

This ballet is the pinnacle of British excellence in dance and music. It is not necessary to appreciate Virginia’s writing style to feel the truth of her experience of the age in which she lived; her loneliness when exiled from London society and denied her own children. This was the post-Suffragette, emancipated age for wealthy women, but young women were still being abused, wives were dominated by more powerful husbands, and a Dr. Holmes’ male view of emotional sensitivity crushed all free thinking as an illness.

Wayne McGregor was awarded the Critics Circle National Dance Award for Best Classical Choreography and the Best New Dance Production for Woolf Works at the Olivier Awards. It was his first full-length production for The Royal Ballet. He has not sought to exactly transcribe Virginia’s words to dance, rather to help the dancers’ emotions tell the story, to truly fall and be swept away, abandoning their learned, instilled control.

Mrs Dalloway

Part 1 of this ballet triptych is Mrs Dalloway, entitled “I Now, I Then”. We hear Virginia talk of linguistic restrictions in a 1937 BBC Recording. Big Ben strikes, Wren church bells mark time. The four repeated bars of Max Richter’s score open into circular strings to keep us inside Virginia’s consciousness.

Leonard is ostensibly calm and caring, while interrupting Virginia’s thoughts and work. Sarah Lamb is our Virginia, gentle and serene, observing her characters from the shadows. She cannot resist reaching into the duets of her characters, to be lifted, to kiss, before pacing alone again around the perimeter of the stage. We see freedom in Wayne’s choreography, to display emotions and follow the music. Splits are allowed and a piggyback to make us smile. Liam Boswell as the ghost of Evans pirouettes the entire quadrangle of the stage as the explosion never leaving Septimus’ brain.

Virginia stands alone at the end, her Tavistock Square backdrop replaced by the garden in Sussex. This first act left me crying in my seat even though this was not the tragic finale. Following the classical tradition of Swan Lake, or Rusalka, we know how this will end.

Orlando

Part 2 – Becoming, from Orlando, is a Starlight Express, circus interlude. It is not clear what the gold-clad figures represented, a mix of X and Y chromosomes? Turquoise beams unfurl curtains of time like the huge bubble wands on the South Bank, misting what lays behind. Where the beams originate, mist gathers like the rippling sea. Just when the disco track feels too much, the conductor raises his wand, the musicians unfold their arms and the earlier musical phrase returns, lower octaves, cellos and double basses, until gentle violins join.

There is a line from Orlando included in the programme:

“The fine fabric of a lyric is no more fitted to contain [the conflict in which writers have to create] than a rose leaf to envelop the rugged immensity of a rock.”

High octane laser beams crisscross turquoise and green across the auditorium. All time is present here and all creativity welcome.

The Waves

Part 3 of the triptych is Tuesday, from The Waves. It draws us down from the gods and forward across the orchestra pit into the sea filling the back of the stage. Gillian Anderson reads Virginia’s love letter, suicide note, to Leonard. It is reproduced in the programme:

“Dearest, I feel certain that I am going mad again… And I shan’t recover this time… So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness… I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer…”

The mid-grey rippled texture of the stage looks at first like wet sand left by a tide just retreated, dappled light reflecting onto it from banked waves behind. Children are playing, Vanessa among them, all dancing, leaping. Virginia withdraws and begins her straight line pacing of her perceived cell. Wayne tells us this is her planning and counting the steps from Monk House to the River Ouse.

The wet sand becomes the sea as the tide returns. Still children play and leap, but now bob as if white caps or white horses, breaking the waves to approach at different heights and speeds. We see rip tides and competing currents eddy between the longer row of dancers.

The last duet with Leonard is dreamlike in Virginia’s head for the minutes she is weighed down under the water. He lays her flat on the banks of the river. She is spared the pain of the future and truths that may emerge about whether her husband’s actions amounted to love. Concealed, inconceivable truths no woman ever sees at the time.

Is this the most evocative half hour of ballet from the past 100 years? Marianna Hovanisyan’s aria drifts above the violin, “as if she were a solitary submerged figure in the oceanic orchestral texture,” as Max Richter writes in the programme.

High in the realm of the angels, this ballet ends with Virginia’s gratitude for love. And extended applause from over two thousand stunned people, who glide out onto Bow Street and the Piazza to a setting winter sun, all of us humming the last refrain, our fingers tapping out the hypnotizing Gᵇ Eᵇ Gᵇ Bᵇ, then F Dᵇ F Bᵇ rhythm. All is calm, all is joy, love ripples the Thames beneath Waterloo Bridge.

To be able to hear this music, to see the best of the Royal Ballet’s dancers, to feel Wayne’s creation; to have the money, mobility and courage to climb into the vertiginous amphitheatre which is all that was affordable; to have the memory of love, of the birth and years of care for one’s own child, these are the gifts of angels. They are reasons to live. To not enter the water alone.

End Notes

- Woolf Works will be performed by the Royal Ballet at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden until 13 February 2026. It will be broadcast live to cinemas around the UK for approx. £11 on 9 February 2026. Note that so much is missed by watching ballet or an opera on a screen because you cannot feel the music or the setting of the chosen theatre. The ROH Youtube channel is also streaming the dress rehearsal from last night.

- Watch this space for a review of Wayne McGregor’s new book We Are Movement, Unlocking Your Physical Intelligence, which was published yesterday.

- Max Richter’s album Three Worlds, Music from Woolf Works, was issued by Deutsche Grammophon in 2017.

- Tracey will perform a poem about Virginia Woolf at the Forthwrite Women’s Festival of Writing in Crawley on Saturday 14 March 2026.

- Look out for the review of Crystal Pite’s Body & Soul for the English National Ballet shortly after 20 March 2026.

- Robert Montgomery has a free exhibition of “The People You Love Become the Ghosts Inside of You” until 12 April 2026 at Charleston, Lewes, East Sussex, the home of Virginia’s sister Vanessa Bell. It is free to sit beside the pond and in the gardens surrounding the house, to watch the beautiful people, as Virginia will have done.

By Tracey Chippendale-Gammell

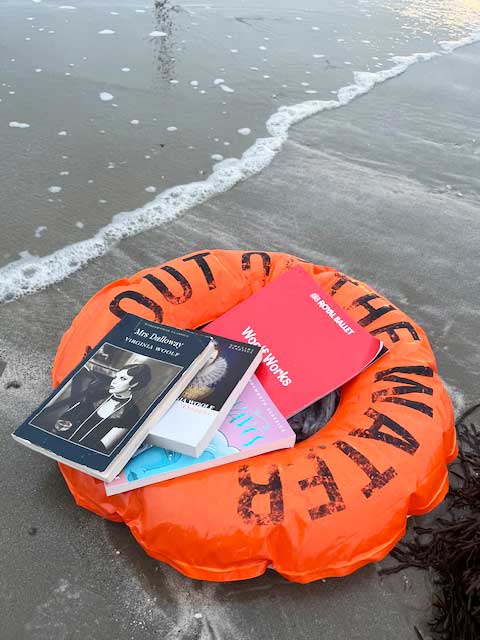

Photo by author

.