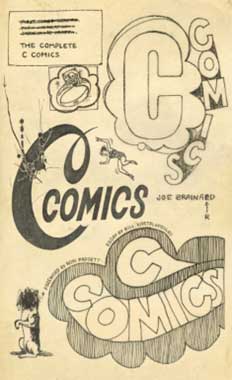

The Complete C Comics, Joe Brainard

Foreword by Ron Padgett, Essay by Bill Kartalopoulos

(New York Review Books)

Every now and then perhaps we need to be reminded, and perhaps now more than ever, that joy exists in the world.

It’s 1960s New York, and the more or less unknown artist Joe Brainard – living on next to nothing but in the thick of the social and energetic milieu of the poets and painters of the New York School – would send drawings of comic-book style pages to poets – not just any ol’ poets: it’s John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, Ted Berrigan, Kenneth Koch, Ron Padgett and loads more; just about anyone who’s anyone in the New York School, in fact – and they would supply words for the caption boxes and speech balloons Brainard had left empty, or put them anywhere else they felt that words might go. Brainard and the poets didn’t plan or discuss things, they didn’t confer . . . for the poets it would have been a bit like getting some do-what-the hell-you-want homework. Sometimes the texts they came up with would be put on the paper by Brainard in a comic-style script, other times the poet’s handwriting would go straight in – but no matter, the spontaneity of the whole enterprise is evident on every page. Mistakes were scrubbed out but the messy blobs were allowed to remain, corrections were made, nobody cared much about neatness, and the poets’ handwriting is often terrible, albeit always readable. Even now, 60 or so years later, the energy comes right off the page, and never flags.

One might think, given these are comics in the 1960s, that you’d have a version of Pop Art, like the Roy Lichtenstein pictures with the static (and, I suppose, ironic) out-take of the comic strip visual and its language, but here the dynamic is totally different. While Brainard may have appropriated the comic strip format, the ways of presenting it are various, and if there’s any narrative (narrative is not a given) it’s conjured up by a New York School poet, and never quite what you might expect. For example, on a page devoted to Wonder Woman, upon which she’s in 4 or 5 different ‘flying’ positions spread across the page, Tony Towle has her at first thinking, in mid-flight, “Only someone’s who’s experienced it can possibly know the heartbreak and humiliation of being rejected”, and finally as she splashes down with a SPLASH! she thinks “. . . so my Irish congressman has to lose his autographed rosary in a vat of strawberry preserves. . . “

C Comics #1 (1964) C Comics #2 (1966)

I’m tempted to list some of the treats these comics have to offer:

James Schuyler contributes several advertisements, including one for the marvellous “The Envy of the Harem” necklace (“Makes wearer irresistible says age-old accredited legend”).

John Ashbery supplies “The Great Explosion Mystery”, which begins by threatening to make sense but then resolutely doesn’t, and opts instead for following one frame and speech bubble e.g. “According to the calendar, winter begins at 8.41 pm on Dec. 21, but according to the New York-Florida railroad timetables the winter season is due to start on Thursday” with several others e.g. “What a time to get a case of the staggers!”

Then there’s Brainard’s own “People of the World: RELAX!” (“Do not be afraid of death. It will not hurt you”. . . . .

But if I start listing the treats I’ll be here all day, so I won’t do that.

But if I start listing the treats I’ll be here all day, so I won’t do that.

In his brief Forword, Ron Padgett recalls that “we did the work simply for the pleasure and adventure of it, with little or no thought of how it might be received by the public. Likewise, it was happily free of theoretical ambitions, such as toward being avant-garde or radical or even funny . . . Ultimately, we were cradled in the sure-handed graphic beauty of Joe’s art.” And of course there is play here, and playful poets have long been frowned upon by other poets who, to quote Kenneth Koch from his poem “Fresh Air”, are firmly under baleful influences and have “their eyes on the myth/ And the missus and the midterms”. Behind the fun and artful artlessness of all of this lurks the sensibility that defines the New York School, whether or not it ever existed or still exists or it’s just a label we all use because we like labels, because they help us to know what we have in front of us. It’s a sensibility which, if it could be summed up in a few words, they would surely be words clamouring to be crossed out and replaced by something much more amusing.

The first issue of the comics was mimeographed on to, as I understand it, far from the best quality paper in the world. (Cheap and very cheerful.) It was what the Americans call legal size paper, which Google tells me is 8½ x 14 inches. The second issue was offset printed on slightly smaller but higher quality paper (8 ½ by 11 inches). Oh, and another thing I love is that for that second issue, Brainard paid the printer $950 for 600 copies, and sold them at $1 a copy, thereby losing money hand over fist. In his own words: “I am afraid that it is a money losing proposition.”

This sumptuous reprint from New York Review Books, as an object to handle and leaf through, is a long way from the 1960s originals, and is a luxurious thing of beauty and joy. But the content of the comics is unadulterated and as pure and fresh as the day they were made. Importantly, the book keeps the large format of the originals so they can be enjoyed to the full. It clocks in at a hefty 14 x 9 inches, and weighs half a ton (or thereabouts) with solid hard covers and superb quality paper. It ain’t cheap, but it’s worth every penny.

.

© Martin Stannard, 2026