Arthur was likely not a historical figure but a mythical hero whose legends were later ‘historicized’ in early medieval Welsh texts. It is noted that the earliest sources present Arthur as a figure of folklore, tied to the landscape and magical elements, similar to the way the Irish hero Fionn was historicized.

One aspect of the Arthurian legend which has often received little consideration is Arthur’s frequent appearance in the topographic folklore of Britain.

For eight centuries, romance has depicted Arthur as king of all Britain, yet very little indeed of the topographic lore has developed in those areas where Anglo-Saxon dominance has been fullest. Arthur, it has been remarked, is more widespread than anybody except the Devil; so perhaps he is, but he is not everywhere. Preponderently, the place-names and local legends belong to the West Country, Wales, Cumbria, southern Scotland – to the Celtic fringe, where Celtic people, descendants of Arthur’s people, maintained a measure of identity longest and in some cases still do. Where a Brittonic language was once spoken.

The first reference to Arthur appears in the 6th: century Welsh poem Y Gododdin, which was written around 594AD and ascribed to Aneririn. Arthur is mentioned by name as a point of comparison for a warrior, suggesting he was already a well-known figure:

Stanza 99. –

‘He fed black ravens on the rampart of a fortress

Though he was no Arthur’.

It has been argued that the name Arthur is derived from ‘bear’, which corresponds with the Celtic bear gods Artos or Artio. Perhaps he was a berserk(er) fighting with mad frenzy. (From bern – bear / serkr – coat). The character developed through Welsh mythology, appearing either as a great warrior defending Britain from human and supernatural enemies or as a magical figure of folklore and was sometimes associated with the Welsh otherworld Annwn.

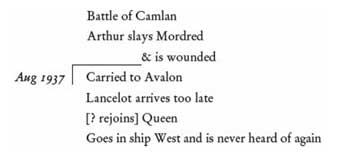

The Fall Of Arthur an unfinished alliterative prose poem by JRR Tolkien, started during the early part of the 1930’s and abandoned around 1937 but unlikely forgotten, was published in 2013 by HarperCollins which contains hints (not in the poem itself, but in what Christopher Tolkien reveals about drafts, outlines and fragments in his editorial matter) about ways in which Tolkien meant to connect his Arthurian legend to his Elvish Legendarium. ‘Arthur dying in the gloom. Robbers search the field (Excalibur >) Caliburn and the Lake. The dark ship comes up the river. Arthur placed upon it’. ‘Lancelot. . . rides ever West. The hermit by the sea shore tells him of Arthur’s departure. Lancelot gets a boat and sails West and never returns’. – Which can be viewed as a symbolic return to his magical origins. (Eärendil also travels to the Western lip of the world and sails upon the sky, never coming back. Tolkien. The Silmarillion, published by George Allen and Unwin, 1977). The Celts viewed the West primarily through a spiritual and mythological lens, associating it with the Otherworld, the realm of the dead, and the setting sun. It was considered a liminal space where the boundary between the mortal world and the divine was thin. Lancelot du Lac (of the Lake) is also associated with fairy of elven themes, being raised by the Lady of the Lake in a Fey realm. Perhaps in a way, Tolkien was mirroring Layamon’s Brut, written in the 13th Century and explicitly states that Elves were present at Arthur’s birth and gifted him with strength, generosity and a long life and because of Arthur’s connection to the supernatural in Medieval literature makes him more of a ‘Fae-kissed’ mortal than a literal, non-human Elf. Layamon also mentions Witege the Smith, a ‘Prince of Elves’ who made Arthur’s armour. The poem itself ends at Canto V (‘Of the setting of the sun at Romeril’) which sees Arthur and Gawain approaching Britain, where a sea battle ensues between their fleet and Mordred’s forces. The final lines depict Arthur in a moment of hesitation, contemplating the ‘ruthless onset’ of the coming battle and wondering if it would be better to wait.

Tolkien’s Note showing the date August 1937

Rooted in Germanic and Anglo-Saxon folklore, Elves were seen as dangerous and powerful entities. Whereas Fairies (the Fae) in Celtic traditions are often depicted as enchantresses from an ‘Otherworld’.

While Merlin – The earliest figure resembling Merlin appears in Welsh tradition as Myrddin the Wild, a prophet and madman who in Welsh poetry was a bard that was driven mad after witnessing the horrors of war and subsequently fled civilization to become a wild man of the wood in the 6th: century. He roamed the Caledonian Forest until he was cured of his madness by Kentigern, also known as Saint Mungo – carrying the dragon standard, the famous Pendragon, an iron piece shaped like a dragon’s head on top of a pole with a long cloth banner attachment trailing behind it – makes him Arthur’s draconarius and implies that Merlin was originally a warrior rather than either a prophet or magician. The dragon standard was first carried by Sarmatian cavalry units in the 2nd: century. Merlin’s attire consists of a robe and hat which was also how the Sarmatian draconarius dressed.

‘Merlin leads the charge using Sir Kay’s special dragon standard that Merlin had gifted to Arthur, which breathes real fire’. Tether, et al. The Bristol Merlin: Revealing the Secrets of a Medieval Fragment. Arc Humanities Press. 2021.

There is another strand of folklore involving Arthur that suggests he may have been a giant, as in some of the myths and legends that are depicted below. Or, at least, people saw him as one. Arthur is sometimes depicted as a giant or associated with giant-like places in folklore, linked to large natural formations with some tales suggesting his immense stature or battles against actual giants, reflecting his larger-than-life heroic status and connection to ancient, powerful landscapes. He is often portrayed as a giant-slayer, but folklore also hints at Arthur himself being a giant or having giant lineage, particularly in Welsh tales where Guinevere’s father was a giant.

Below, these folkloric tales root Arthur in specific landscapes, portraying him as a mythical leader of heroes in wild, magical places, distinct from the later literary courtly figure. Many sites use natural features or prehistoric monuments, suggesting these stories existed before written accounts and were central to the legend’s origins.

Prehistoric Sites Specific To Arthur.

There are many prehistoric sites which are named ‘Arthur’s Stones’ or ‘Arthur’s Quoits’ and are central to Welsh folklore with its rich tapestry of myths, legends from Celtic roots, featuring giants, dragons, magical beings and heroes. With ‘Arthur’s Stones’ the implication is that these are enormous and remarkable stones that Arthur’s gigantic strength allowed him to make his mark upon. Whereas the name ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ (‘quoit’ meaning ‘discus, a solid circular object thrown for sport’) is usually applied to a cromlech and probably originally referred to the capstone of such prehistoric structures. Such features, when not being named after Arthur, are frequently associated with giants and reflect the concept of Arthur as a giant. A number of sites specific to Arthur have been lost over time:-

An ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ or ‘Giant’s Quoit’ cromlech in St: Columb Major parish, Cornwall. The structure collapsed in the mid-19th: century and its stones were subsequently split up, buried, or used in surrounding hedges by the 1970’s.

A lost ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ at the Pembroke estuary.

A capstone destroyed in 1845 in Llanllawer parish, Pembrokeshire.

A lost ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ in Caernarvonshire.

‘Coetan Arthur’ or ‘Ystum-Cegid Burial Chamber’. Llanystumdwy. Gwynedd. The remains have been much disturbed and are now incorporated in a modern field system wall.

A 17 feet long stone known as ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ but now lost, near Llwydiarth, Anglesey.

Arthur’s Stones & Quoits.

Trethevy Quoit near St: Cleer, Cornwall is sometimes called ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ or ‘The Giant’s House’.

‘Arthur’s Stone’ A Neolithic or Bronze Age burial-chamber found in Herefordshire and first recorded in the thirteenth century. Patel. The Nature Of Arthur. 1994 and said to be where Arthur killed a giant, with marks in one of the stones being made by the giant’s elbows as he fell.

A double megalithic chambered tomb with capstone in Llanrhidian Lower on the Gower peninsula: ‘Legend has it that when Arthur was walking through Carmarthenshire on his way to Camlann, he felt a pebble in his shoe and tossed it away. It flew seven miles over Burry Inlet and landed in Gower, on top of the smaller stones of Maen Cetti.’ – Grooms. The Giants of Wales: Cewri Cymru. Mellen 1993.

The 25 ton capstone of an ancient burial chamber near Reynoldston, north of Cefn Brynis, Gower Peninsula is called ‘Arthur’s Stone’ and his ghost is occasionally said to emerge from underneath it – it is explained as a stone that was tossed from Arthur’s shoe.

An ‘Arthur’s Stone’ near Penarthur, Pembrokeshire and related in folklore to a ‘Coetan Arthur’ (‘Arthur’s Quoit’).

An ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ (the remains of a burial chamber) recorded in Newport parish, Pembrokeshire.

An ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ in Mynachlog-ddu parish, Pembrokeshire, said to have been hurled by Arthur from Henry’s Moat parish, where there is a stone circle associated with ‘Arthur’s Grave’ and ‘Arthur’s Cairn’.

‘Coetan Arthur’ (also known as ‘Arthur’s Quoit’), St: David’s Head, Pembrokeshire, close-by an ‘Arthur’s Hill’ – numerous instances of this name are recorded. – Legend states that Arthur played quoits with the stones.

An ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ at Pentre Ifan, Pembrokeshire, also known as ‘Ivan’s Village’.

An ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ or ‘King’s Quoit’ cromlech near Manorbier, Pembrokeshire.

‘Carreg Coitan Arthur’, a Bronze Age standing stone (menhir) in Pembrokeshire. The site is associated with Arthurian folklore, and the name translates roughly to ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ or ‘Arthur’s Stone’. Arthur created the structure by throwing the stones from the nearby rocky outcrop of Carn Llidi.

An ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ with ‘a trace of Arthur’s thumbmark … plainly seen on it now’ was tossed to Llangeler and Penboyr by Arthur from Pen Codfol; ‘another of the giant’s quoit landed on the land of Llwynffynnon; this place is called ‘Cae Coetan Arthur’. Patel. The Nature Of Arthur. 1994.

An ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ in Llangadog parish, Carmarthenshire – this is a large rock in the river Sawddwy, which Arthur flung into position from ‘Pen Arthur’, a mile distant, and is accompanied by a similar large rock that was tossed from the shoe of a lady acquaintance of Arthur. Grooms. The Giants of Wales: Cewri Cymru. Mellen 1993.

An ‘Arthur’s Stone’ (‘Maen Ceti’) in Bettws, Carmarthenshire. The most famous legend states that Arthur, while walking in Carmarthenshire, found a pebble in his shoe. He tossed it in frustration across the Loughor Estuary, and it landed on Cefn Bryn, growing magically to its enormous size upon touching the ground.

An ‘Arthur’s Stone’ lying at the top of a hill in ‘Maen Arthur Wood’ near Pont-rhyd-y-groes, Ceredigion, with the name of Arthur’s horse present in nearby Rhos Gafallt.

An ‘Arthur’s Stone’ in Llanddwywe-is-y-graig, Gwynedd, also known as ‘Gwern Einion Burial Chamber’.

A stone circle known as ‘Arthur’s Stones’ in Llanaber, Gwynedd, also known as ‘Cerrig Arthur’.

An ‘Arthur’s Stone’ in the parish of Dolbenmaen, Gwynedd. Historical records, such as those found in journals like Archaeologia Cambrensis, indicate a mention of an Arthurian site in or near Dolbenmaen, but generally, only the name survives, not the original explanatory folk-tale.

A cromlech named ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ is found in Myllteyrn parish, Gwynedd. Grooms translates the following from Myrddin Fardd (writing in the nineteenth century), which is worth repeating for its illustration of the local folkloric traditions surrounding these stones:

‘A multitude of tales are told about him [Arthur]. Sometimes, he is portrayed as a king and mighty soldier, other times like a giant huge in size, and they are found the length and breadth of the land of stones, in tons in weight, and the tradition connects them with his name – a few of them have been in his shoes time after time, bothering him, and compelling him also to pull them, and to throw them some unbelievable distance. . . A cromlech recognized by the name ‘Coetan Arthur’ is on the land of Trefgwm, in the parish of Myllteyrn; it consists of a great stone resting on three other stones. The tradition states that ‘Arthur the Giant’ threw this coetan from Carn Fadrun, a mountain several miles from Trefgwm, and his wife took three other stones in her apron and propped them up under the coetan’. Grooms. The Giants of Wales: Cewri Cymru. Mellen 1993.

Three ‘Arthur’s Quoits’ are mentioned in the nineteenth century in Ardudwy, Gwynedd, where ‘the tradition states that Arthur threw it [them] from the top of Moelfre to the places where they rest presently. It is believed that marks of his fingers are the indentations to be seen on the last stone that was noted’. Ibid.

‘Arthur’s Quoit’, Rhoslan refers to a Neolithic burial chamber.

An ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ in Llanjestin parish, Gwynedd recorded in the seventeenth century. As with other sites bearing Arthur’s name, the large stones are traditionally believed to be the ‘quoits’ used by the giant Arthur in a game.

An ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ recorded in 1838 in Gwynedd, is a megalithic tomb, likely the remains of a Neolithic burial chamber (dolmen) known as ‘Coetan Arthur’.

An ‘Arthur’s Stone’ (in Denbigh) where a giantess called on ‘Arthur the Giant’ from the Eglwyseg Rocks for help against St: Collen.

The following prehistoric sites, which also claim to be associated with Arthur, should be included with the above listing.

‘Arthur’s Table’ (a flat topped stone) associated with Arthur is that at the boundary of Gulval, Zennor and Madron in Cornwall, where Arthur is said to have dined before defeating the invading Vikings of far-western Cornwall. Courtney. Cornish Feasts and FolkLore. Beare & Son. 1890. Also known as ‘Arthur’s Quoit’, it is the capstone of a Neolithic burial chamber. A similar legend is also attached to ‘Table Mên’, Sennen (Cornwall). Hunt. Popular Romances of the West of England; or, the Drolls, Traditions, and Superstitions of Old Cornwall. Hotten. 1865.

‘Arthur’s Hall’, an enigmatic Neolithic monument located on Bodmin Moor, near the village of St Breward, Cornwall, first recorded by John Norden in the sixteenth century. It consists of a rectangular bank (enclosing marshy ground) with a rectangle of upright granite slabs within. It was also known as ‘Arthur’s Hunting Lodge’ – or ‘Hunting Seat’ an Iron Age hill fort in Castle-an-Dinas, Cornwall, near St: Columb, from which Arthur rode in the hunt on Tregoss Moor – a stone in St: Columb bears the four footprints that his horse made whilst he was out hunting. – Nearby is ‘Arthur’s Bed’ – takes the form of a granite monolith on top of a hill, with a natural hollow in it shaped like a human torso. The first record of it is found in the works of an eighteenth century Cornish antiquary, William Borlase writing in 1754, who accompanies his description with the following remarks:

‘Round Arthur’s Bed, on a rocky Tor in the parish of North-hill, there are many [rock-basins], which the country people call Arthur’s Troughs, in which he us’d to feed his Dogs. Near by also, is Arthur’s Hall, and whatever is great, and the use and Author of unknown, is attributed to Arthur’.

There are also ‘Arthur’s Troughs’ and ‘Arthur’s Downs’.

Eamont Bridge, Cumbria which is an earthwork known as ‘Arthur’s Round Table’. This is a henge dating from the late Neolithic period.

An ‘Arthur’s Table’ in Mynydd Llangyndeyrn. A pair of Neolithic burial chambers which are also called ‘Bwrdd Arthur’.

Gwal y Filliast chambered tomb, Carmathenshire, the circular hole is known as ‘Arthur’s Pot’. The earliest record of Gwal y Filiast is from Edward LLuyd in 1695, who notes – ‘Gwaly Viliast or Bwrdh Arthur in Llan Boudy parish, is . . . a rude stone about ten yards in circumference, and above three foot thick, supported by four pillars, which are about two foot and a half in length.’ Also Wirt Sikes wrote in his book, British Goblins from 1880: ‘Under a cromlech at Dolwillim, on the banks of the Tawe, and in the stream itself when the water is high; there is a circular hole of considerable depth, accurately bored in the stone by the action of the water. This hole is called Arthur’s Pot, and according to local belief was made by Merlin for the hero king Arthur to cook his dinner in.’

Arthurian Landscape.

Arthurian associations can be found in ancient hillforts, natural landscape phenomena and that of man-made constructions. There are also a number of topographic features bearing the name ‘Arthur’s Seat’. In all cases, the concept of Arthur would seem to be, once again, that of a giant, with these enormous rock-formations providing him furniture whilst he roamed the wilds of the landscape, just as they do for other giants in non-Arthurian giant-lore.

‘Great Arthur’ and ‘Little Arthur’ refer primarily to two uninhabited islets in the Isles of Scilly, known for prehistoric passage graves, but can also hint at legendary figures like ‘Arthur the Less’, Arthur’s son in some romances and the historical figures potentially inspiring the myth, differentiating the legendary Great Arthur from lesser-known Arthurs. Some historians propose that figures like Artuir mac Áedán (a 6th: century Scottish war leader) or Roman officer Lucius Artorius Castus might be the historical basis for the Arthur legend, representing different Arthurs.

Tintagel. The site is associated with Arthur’s conception, his father Uther Pendragon and Merlin, who is said to have rescued the infant Arthur from ‘Merlin’s Cave’ below the castle.

‘Arthur’s Cups and Saucers’ are twenty small circular depressions, 5 – 15cm: across, found on the headland at Tintagel, Cornwall, where there is also an ‘Arthur’s Chair’ – which has initials purporting to date back to the seventeenth century cut into it and a slit known as the Window. Thomas. Tintagel: Arthur and Archaeology. Batsford. 1993., ‘Arthur’s Footprint’ – this is found on the headland at Tintagel, Cornwall, on the highest point of the island. It was recorded as ‘Arthur’s Footstep’ in 1872 and his ‘Footprint’ in 1901 and 1908, it takes the form of an eroded hollow, the base of which has the shape of a large human footprint. It is reputed to have been imprinted in the solid rock when Arthur ‘stepped at one stride across the sea to Tintagel Church’ (1889) and thus may be seen to parallel tales from other areas where Arthur is a giant who leaves impressions on various rocks. While it has been suggested that the hollow may actually have had a ceremonial use in the post-Roman period, and nearby, an ‘Arthur’s Quoit’.

Treryn Dinas, an ancient fort in Cornwall, is claimed to have been a ‘castle’ of Arthur.

‘Battle of Camlann’: Arthur’s final, fatal battle against Mordred, where both perished. This conflict is strongly linked to the River Camel in northern Cornwall, near Slaughterbridge, a site steeped in local tradition. Another suggested location is a present-day Camlan in Gwynedd, Wales, or along the River Cam in Somerset.

‘Arthur’s Slough’ – the following is recorded in Notes & Queries, volume 10, third series, December 29 1866, p.509:

‘On my way from Wells to Glastonbury some years since, I overtook on the road a countryman who pointed out to me a morass which he said was known in those parts as Arthur’s Slough. Can ‘N. & Q.’ inform me whether any tradition of King Arthur, who was buried at Glastonbury, attaches to this marsh?’

Cadbury Castle, Somerset, was recorded as Arthur’s Camelot in the sixteenth century by Leland. The name ‘Camelot’ seems to have only become attached to the Arthurian legend in the late-twelfth century and has no place in British traditions, as indicated by Trioedd Ynys Prydein. In 1586, however, it was recorded that locals called Cadbury Castle ‘Arthur’s Palace’ – a name which could conceivably have preceded (and informed) its designation as Camelot, in light of the Liber Floridus – and the presence of ‘Arthur’s Hunting Causeway’ – this is found beside Cadbury Castle and is an ancient track passing the camp towards Glastonbury. In addition to evidencing ‘Arthur the hunter’ it would seem to be related to the widespread folkloric belief that Arthur led the ‘Wild Hunt’, with tales of Arthur and his men riding along this at night-time, invisible except for the glint of silver horse shoes. The riders are said to stop to water their horses at ‘The Wishing Well’. Palmer, et al. An ‘Arthur’s Well’ is found in the lowest rampart of the fort. In this area Arthur and his knights are said to ride at night in the Wild Hunt and water their horses either here or at another well by the village church of Sutton Montis. Chambers. Arthur Of Britain. Sidgwick & Jackson. 1927.

Cadbury Castle. CRB Barrett. 1893. Public Domain

‘Mons Badonicus’ (‘Mount Badon’): This is Arthur’s most famous battle, where he is said to have achieved a great victory over the Saxons. While its historicity is certain from the 6th: century writer Gildas’s mention, he did not associate it with Arthur. Later folklore identified numerous hills as the site. One proposed location is Braydon in Wiltshire, while others place it in Somerset or other regions, each with its own local support.

‘Stone Arthur’ is on top of a mountain in Cumbria, a distinctive rock formation, or cairn.

‘Burum Arturi’, ‘Arthur’s Bower’, that is probably ‘bed-chamber’. This is a topographic feature located in Carlisle and first recorded in the 1170’s.

‘Arthur’s Well’, Walltown Crags: this well may now be destroyed or lost.

The ‘River Glein’ and ‘River Dubglas’: These are sites of early battles in the Historia Brittonum battle list. Identifications often centre on Southern Scotland / Northumberland. The ‘River Glein’ is identified by some scholars as the Glen in Northumberland, and the ‘River Dubglas’ as the Douglas Water near Lanark.

‘Kairarthur’ (also spelt ‘Kaerarthur’ or ‘Caerarthur’) is an old Welsh name, meaning ‘Arthur’s Fort’ or ‘Arthur’s city / castle’. It is primarily associated with Arthurian folklore and has been linked to several different historical and mythical locations, rather than one specific, universally accepted hill.

‘Buarth Arthur’, (‘Arthur’s Enclosure’), is the remains of a stone circle in Carmarthenshire.

Caerleon, Monmouthshire where the old Roman amphitheatre was known as the ‘Round Table’ and a potential location for Arthur’s court.

‘Kelli wic’ meaning ‘forest grove’ appears in some of the earliest Arthurian tales, such as the early dialogue poem Pa gur yv y porthaur, a fragmentary, anonymous poem in Old Welsh, taking the form of a dialogue between Arthur and the gatekeeper Glewlwyd Gafaelfawr and also the eleventh century Culhwch ac Olwen.

‘Llys Arthur’, ‘Castell Llys Arthur’ or ‘Arthur’s Court’ lies close to the site of Cei and Bedwyr’s battle with Dillus Farfog. Cei and Bedwyr searched and eventually found Dillus on top of Pumlumon, a mountain range in Wales. They saw a great smoke and discovered Dillus cooking and eating a wild boar. Dillus was described as the ‘mightiest warrior that ever fled from Arthur’. Once Dillus was asleep, Cei dug a large pit beneath him. They struck the giant on the head and forced him down into the pit. Using wooden tweezers, they plucked his beard entirely while he was alive. After securing the beard, Cei and Bedwyr killed Dillus and brought the macabre prize back to Arthur’s court at ‘Kelli Wic’.

‘The Spring of Arthur’s Kitchen’ (‘Ffynnon Cegin Arthur’) in Llanddeiniolen, Gwynedd, is an historic chalybeate spring located in forestry land, known for its legendary connection to Arthur.

Moses Williams (1685 – 1742) records ‘Arthur’s Spear’ (a thin standing stone) ‘close to the Llech at one end of the way that leads from Bwlch-y-ddeufain to Aber’ in Gwynedd. Local folklore states that the stone was originally a spear or staff belonging to Arthur. According to the legend, Arthur was gathering sheep on Pen y Gaer when his sheepdog ran off to seek shelter in a nearby dolmen (the chamber known as ‘Cwrt-y-Filiast’, or the ‘Kennel of the Greyhound’. In exasperation, Arthur threw his spear across the valley toward the hound; the stone marks where it landed.

Yr Wyddfa (Snowdon) is deeply connected to Arthur in Welsh legend, most famously as the burial site of the giant Rhita Gawr, whom Arthur defeated in battle, with the summit’s cairn marking the giant’s head. Other Arthurian links include the ‘Bwlch y Saethau’ (‘Pass of the Arrows’) where Arthur was wounded.

‘Bwrdd Arthur’ hill fort, also known as Din Sylwy, is located on the island of Anglesey.

The Celidon Wood (‘Battle of Celidon’) is likely located in the Southern Uplands or the moorlands around the upper Clyde and Tweed valleys.

‘Loch Arthur’ a freshwater loch in Dumfries & Galloway, believed by some to be the setting for the Lady of the Lake story.

‘Arthur’s Oven’ (known locally as ‘Arthur’s O’on’) was a unique circular Roman stone structure located near Stenhousemuir. The structure was well-documented by antiquarians but was controversially demolished in 1743 by the landowner, Sir Michael Bruce of Stenhouse, to use the stones for repairing a mill weir on the River Carron.

‘Arthur’s Fold’ (historically spelt ‘Arthur’s-fold’) was a farm located in the parish of Coupar-Angus in Perthshire. It was situated near a standing stone known as the ‘Stone of Arthur’. The farm and surrounding landmarks are linked by tradition to the Arthurian cycle. At the nearby Meigle churchyard, antique monuments are traditionally associated with Arthur’s queen, Guinevere. (Locally known as Vanora or Wanda). These traces are considered some of the most northerly surviving examples of the Arthurian legend in Scotland. ‘Varona’s Mound’ is a round barrow and documentary references going back to the early sixteenth century described the Mound as having been furnished with a number of Pictish stones, included in these was the great ‘Vanora Stone’.

There are numerous ‘Arthur’s Caves’, particularly as a number of these have stories attached in which he takes temporary refuge there, or slumbers there eternally. Caves, real or legendary, with Arthurian associations include Cadbury Castle, Caerleon, Snowdonia, Ogo’r Dinas, Alderley Edge, Craig-y-Dinas, Melrose, Richmond, Marchlyn Mawr, Sewingshields, Llantrisant, Pumsaint, Threlkeld and Sneep. There is an ‘Ogof Arthur’ in Angelsey, another in Merioneth and one or two more three miles north of Monmouth above the River Wye in Herefordshire.

Arthur’s Seats.

An ‘Arthur’s Chair’ north-west of Sewingshields, Northumberland. This is found at King’s Crags and has its pair in Queen’s Crags, where there is ‘Gwenhwyfar’s Chair’. Arthur, clearly conceived of as a giant, supposedly threw a boulder from his chair at Gwenhwyfar which bounced off of her comb to land on the ground, with the teeth-marks from the comb still visible on the rock. The chair was a natural geological feature, described in historical accounts (like Hodgson’s Northumberland Part III Vol II) as a ‘single, many-sided shaft, about ten feet high, and had a natural seat on its top, like a chair with a back’. The natural rock formation was wantonly overturned during the 19th: century and no longer exists in its original form.

‘Cadair Arthur’ (‘Arthur’s Chair’): Both Pen-y-Fan (the highest peak in South Wales) and the Sugar Loaf (Mynydd Pen-y-fâl), Monmouthshire were historically referred to as ‘Cadair Arthur’ or ‘Arthur’s Seat’, due to the two peaks resembling a chair. This association with a throne ties the mountain to the most important king of the Britons in local folklore and early texts. While not directly linked to the Pen-y-fâl name itself, a legend associated with the Brecon Beacons area (where the mountain is located) tells of Arthur helping the local people fight a group of wild boars. Arthur is said to have killed the alpha boar, whose body rolled into a river now called the Afon Twrch, which means ‘river of the boar’ in Welsh.

‘Idris’s Chair’ is the English translation of Cadair Idris, a prominent mountain in Gwynedd, Wales, which features in local folklore and Welsh mythology. While it is sometimes associated with Arthur in popular culture, the traditional legends primarily revolve around a giant or a 7th: century prince named Idris.

A mountain in the Hart Fell area, Dumfriesshire is known as ‘Arthur’s Seat’.

‘Arthur’s Seat’ is an ancient extinct volcano that is the main peak of the group of hills in Edinburgh, Scotland. first recorded as Arthurissete in 1508.

An ‘Arthur’s Seat’ at Dumbarrow Hill, Angus was mentioned in the Old Statistical Account No: XLIII p. 419 from 1791.

In addition to the above categories of Arthurian topographic folklore, we have a number of other features and places named after Arthur or associated with him.

The ‘Stones of the Sons of Arthur’ are a group of standing stones in Mynachlog-ddu, Pembrokeshire where there are numerous other Arthurian sites. They are apparently meant to represent the site of a battle.

‘Carn Cafal’ (or ‘Carn Gafallt’) refers to a legendary location in Mid: Wales, a hill marked by prehistoric cairns where Arthur’s dog, Cabal (or Cafall), supposedly left his paw print in a stone while hunting the great boar Twrch Trwyth; a magical stone with the print, if removed from its cairn, would mysteriously return the next day, making it a famous Arthurian landscape wonder.

In Welsh folklore, the ‘Stone of Arthur’s Steed’s Hoof’ refers primarily to two distinct locations in Wales where natural indentations in rock are attributed to the hoofprints of Arthur’s horse, Llamrai. The most prominent site is located near Llyn Barfog (the Bearded Lake) in the hills above Aberdyfi, Gwynedd. The monster Afanc, a water demon, lived in Llyn Barfog and terrorized the surrounding countryside. Arthur lassoed the creature with a magical chain and used his horse, Llamrai, to haul it from the lake. The struggle was so intense that Llamrai’s hoof left a deeply etched print in a nearby rock. A second site with the same name is found in the Clwydian Mountain Range, In this version, the hoofprint was made as Arthur and Llamrai leapt from a nearby cliff to escape invading Saxons.

But Arthur’s Grave Is Nowhere Seen.

The Passing Of Arthur. Hawes Craven. 1895. Public Domain

The possibility of Arthur’s return is first mentioned by William of Malmesbury in 1125: ‘But Arthur’s grave is nowhere seen, whence antiquity of fables still claims that he will return.’ In the Miracles of St. Mary of Laon (De miraculis sanctae Mariae Laudunensis), written by a French cleric and chronicler named Hériman of Tournai in circa 1145, but referring to events that occurred in 1113, mention is made of the Breton and Cornish belief that Arthur still lived. Various non-Welsh sources indicate that this belief in Arthur’s eventual messianic return was extremely widespread amongst the Britons from the 12th: century onwards. How much earlier than this it existed is still debated. The belief that King Arthur is asleep in an enchanted cave, to be awakened at his country’s time of need. The Cave Legend is found primarily in oral folklore: chronicles and romances have Arthur living not in a cave, but on the island of Avalon. Merlin is also believed to be sleeping in caves in various places.

‘Arthur’s’ or ‘Giant’s Grave’ at Warbstow refers to a large, medieval pillow mound within the massive Iron Age hillfort of Warbstow Bury in Cornwall. Stories say a giant from Warbstow fought others and was buried here, or that it’s Arthur’s tomb.

The most famous ‘grave’ is, of course, that found at Glastonbury.

‘Gwely Arthur’, near ‘Pen Arthur’, Pembrokeshire, is the local name for ‘Bedd Arthur’, a late Neolithic stone circle or hengiform monument located in the Preseli Hills. This enigmatic site, whose name translates to ‘Arthur’s Grave,’ consists of thirteen standing stones (and at least two fallen ones) arranged in an oval or horseshoe shape on a low bank. Local legend claims the site is the final resting place of Arthur. However, some sources suggest it might be associated with a historical 7th: century ruler of Dyfed named Arthur Petr.

‘Bedd Arthur’ (‘Arthur’s Grave’) is associated with ‘Arthur’s Quoit’ in Mynachlog-ddu parish, near the source of Stonehenge’s bluestones, a region filled with Arthurian-named sites.

Craig y Ddinas located in the Brecon Beacons, this site is associated with a legend of Arthur and his knights sleeping in a hidden cave guarding treasure.

There is a ‘Carnedd Arthur’ (‘Arthur’s Cairn’) at Snowdonia, where Arthur was supposedly buried after Mordred killed him at Camlann (the battle is reported to have been fought in a nearby valley) and which has a ‘cave legend’ attached to it.

Another cairn, known as ‘Arthurhouse’, is the most northerly piece of Arthurian place-lore and located at Garvock, Kincardineshire. The connection to Garvock is a fascinating example of how the Arthur legend spread far into Pictish territory, linking specific Scottish landmarks to the broader British myths

According to some tales, Arthur pulled Excalibur from a stone to prove his kingship. Another version says the Lady of the Lake gave him the sword. The Lady of the Lake is a mysterious figure from Arthurian legend, typically a powerful enchantress or fairy associated with water. She is also known by the names Viviane or Nimue and has several key roles, including raising Lancelot and imprisoning Merlin after learning his secrets. The character is a prominent and often ambiguous figure with both benevolent and sinister interpretations across different stories. Dozmary Pool In Cornwall, is a popular location where the Lady of the Lake is said to have emerged to present Arthur with Excalibur. Along with Llyn Llydaw, Llyn Dinas and Llyn Ogwen, these lakes are in Snowdonia National Park, Wales and are all contenders for the final resting place of Excalibur, Arthur’s magical sword, which was returned to the Lady of the Lake. As Arthur lay mortally wounded, he ordered Bedivere (In early Welsh sources, Bedwyr Bedrydant, a one-handed warrior under Arthur’s command), to throw the sword into a lake.

Miscellaneous Arthurian.

In topographic folklore the Arthurian legends feature many characters, including Arthur’s ‘heroic band’ of warriors and members of his family who have also left their mark on the landscape.

Merlin.

Based on figures from Welsh mythology like the bard Myrddin Wyllt. Merlin is known for his powerful magic, including prophecy, shape-shifting and creating storms and illusions. According to most versions of the legend, Merlin was eventually trapped forever by the enchantress Nimue (often referred to as the Lady of the Lake) and lost his position as Arthur’s advisor.

Tintagel: ‘Merlin’s Cave’ is a large sea cave beneath Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, linked to the legend of Arthur’s conception and Merlin’s ghost is said to wander there.

‘Marlborough Mound’: This large, prehistoric artificial hill on the grounds of Marlborough College in Wiltshire is, according to local legend, the final burial place where Merlin was interred, or, in another version, where he was imprisoned by the Lady of the Lake. The town’s name itself is sometimes folk-etymologized as ‘Merlin’s Barrow’.

Carmarthen: The town’s Welsh name literally translates to ‘Merlin’s Fortress’. He is traditionally considered to have been born here. A famous local prophecy states: ‘When Merlin’s Oak shall tumble down, then shall fall Carmarthen Town’. When the remnants of the original oak were removed in 1978, the town experienced significant flooding shortly after, a fact often cited as a fulfillment of the prophecy.

‘Merlin’s Hill’ (‘Bryn Myrddin’): Located near Carmarthen, this prominent hill is said to contain a cave where Merlin was imprisoned by the Lady of the Lake (Nimue or Vivien). Local folklore suggests that one can still hear his groans or lamentations if they listen carefully.

‘Merlin’s Chair’ (‘Cadair Myrddin’): A rock resembling a chair at the summit of ‘Merlin’s Hill’, where he is said to have sat to have his prophetic visions.

Dinas Emrys: This hillfort in Snowdonia is the site where a young Merlin (Myrddin Emrys) prophesied to King Vortigern that the reason his castle kept collapsing was due to an underground lake where two battling dragons (red and white) resided. The red dragon’s eventual victory was seen as an omen for the Welsh triumph over the Saxons, a legend linked to the Welsh national flag.

Drumelzier: In medieval Scottish legend, the historical figure behind the myth (Lailoken or Myrddin Wyllt) is said to have been buried near the confluence of the River Tweed and the Powsail Burn (now Drumelzier Burn). A prophecy foretold that the Tweed would flood to meet the burn at his grave when Scotland and England had one king, which locals linked to the crowning of James VI in 1603.

‘Forest of Celidon’ (Celyddon): After the battle of Arfderydd in 573, the original ‘wild man’ figure of Merlin fled into this ancient, dense forest (in modern-day southern Scotland) to live as a hermit and prophet, deeply connected to the natural world.

Uther Pendragon.

Uther Pendragon’s topographic folklore consists of legendary associations between his mythic deeds and physical landmarks across Britain, primarily in Cumbria, Cornwall and Wiltshire. While medieval chroniclers like Geoffrey of Monmouth established his narrative, local traditions have anchored his story to specific sites through names and physical features of the landscape. In some Arthurian folklore. Uther Pendragon adopted his name and title after witnessing a dragon-shaped comet. The sight inspired him to use the dragon as his standard and the title ‘Pendragon’, meaning ‘chief dragon’ or ‘head dragon’ in Welsh, as a symbol of his sovereignty and a powerful omen of his reign. A few minor references to Uther appear in Old Welsh poems where Uther is mentioned as one of the creators of The Three Great Enchantments of the Island of Britain that represented potent magic, shapeshifting and illusion to Menw son of Teirgwaedd. Since Menw was a shapeshifter according to Culhwch and Owen, it might be that Uther was one as well. If this is so, it opens up the possibility that Uther changed his own shape to impregnate Igraine.

‘Pendragon Castle’ (Cumbria): Located in the Mallerstang Valley, this site is traditionally cited as Uther’s stronghold and birthplace.

‘The River Diversion Legend’: Local folklore claims Uther attempted to divert the River Eden to create a moat for the castle. His failure is immortalized in a Cumbrian rhyme: ‘Let Uther Pendragon do what he can, Eden will run where Eden ran’. In essence, it is a proverb about the limits of power against natural destiny or established order, using a classic Arthurian legend as its source.

‘The Poisoned Well’: Tradition holds that Uther and 100 followers died after Saxon invaders poisoned the castle’s well.

‘Nine Standards Rigg’, Cumbria: Some topographic theories link Uther to the ‘toothed mountain’ (Mynydd Daned) mentioned in early manuscripts, where the Britons supposedly routed the Saxons.

Local legends at ‘Pendragon Castle’ describe the ghost of Uther walking the ruins at night, searching for his son Arthur.

Guinevere.

In Arthurian folklore, Guinevere’s character is deeply intertwined with the physical landscape of Britain, ranging from specific archaeological sites and burial claims to symbolic representations of the land itself. Topographic legends associate her with varied locations across England, Wales and Scotland, often reflecting themes of abduction, sovereignty and seclusion.

An Iron Age hillfort near Oswestry, known in Welsh tradition as ‘Caer Ogyrfan’, is locally identified as Guinevere’s birthplace. Early Welsh Triads name her as the daughter of Gogyrfan (or Ogfran), a warrior chieftain who reportedly ruled from this stronghold in the late 400’s.

‘Tarn Wadling’ (Cumbria): This real-world tarn (mountain lake) in northern England is the primary setting for the 15th: century romance The Awntyrs off Arthure at the Terne Wathelyne. In this folklore, Guinevere encounters the ghost of her undead mother rising from the water, tying the narrative to a specific physical biome. At the lake Tarn Wadling, Gawain and Guinevere (‘Gaynour’) encounter a hideous and vividly-described ghost, who reveals that she is Guinevere’s mother, condemned to suffer for the sins of adultery and pride that she committed while alive. In response to Gawain and Guinevere’s questions, she advises them to live morally and to ‘have pité on the poer [. . .] Sithen charité is chef’ (‘have pity on the poor [. . .] Because charity is paramount’) and also prophesied that the Round Table will ultimately be destroyed by Mordred, She ends by requesting that masses are said for her soul.

Some scholars interpret Guinevere as a personification of the land itself – a Celtic goddess of sovereignty. In this view, her marriage to Arthur ensures the fertility and prosperity of the realm; when the king grows old or ‘maimed’, the land becomes a wasteland, necessitating a younger, virile replacement to restore the landscape. Her frequent abductions—by figures like Melwas of Somerset or Meleagant – are sometimes interpreted as parallels to the Greek Persephone or Irish Étaín myths. In these tales, her abductor takes her to an ‘Otherworld’, sometimes topographically identified with Glastonbury (the ‘Island of Glass’ or Avalon. – Morgan le Fay is primarily rooted in her association with the mythical ‘Isle of Avalon’ where she bears the mortally wounded Arthur by boat to its shores at the end of his life. Folklore identifies Tintagel Castle as her birthplace and where she was raised as the daughter of the Duke of Cornwall. As ‘Queen of the Faeries’, her presence is often associated with fairy mounds from which she emerges to deliver prophecies.

Arthur’s Knights(?).

In topographic folklore, Arthur’s knights(?) are often depicted as a band of heroes living outside conventional society, with their deeds anchored to remarkable natural features, prehistoric antiquities and specific landmarks across Britain. The earliest warriors associated with Arthur, appearing in Welsh texts before the Round Table even existed, are Kay (Cei) and Bedivere (Bedwyr), often depicted as Arthur’s companions in battle alongside Bedwyr’s brother and Lucan – nicknamed the Black Wolf of the North, forming a core group in early legend, predating the elaborate chivalric romances. Other foundational figures include Arthur’s kin like Gawain (Gwalchmei), who appears early in Welsh tradition and sometimes Griflet, an early companion.

Y Lliwedd: In a cave just below the summit of this nearby mountain, Arthur’s knights are said to lie in slumber, ready to awake and fight again for Wales.

Amr.

Located in the region of Archenfield, Herefordshire, near the Welsh border. The story describes a tomb next to a spring called ‘Licat Amr’ (Welsh for ‘Amr’s Eye’ or ‘source of the Gamber river’, as ‘licat’ means ‘eye’ or ‘source’). The tomb is described as having a magical property: no matter how many times it is measured, its length is never the same twice, varying between six, nine, twelve, or fifteen feet. The accompanying narrative states that Arthur killed his own son Amr and buried him in that very spot.

Bedwyr (Bedivere).

One of the earliest direct references to Bedwyr (Bedivere) can be found in the 10th: century poem Pa gur which recounts the exploits of a number of Arthur’s men, including Bedwyr and Cei (Kay), – Cei’s legend appears to have originated, in part, from disparate local folk tales tied to distinctive landscape features and Manawydan, – Manawydan fab Llŷr is associated with specific locations in Wales, particularly the region of Dyfed, which is central to the third branch of the Mabinogi named after him. While the stories reference real places, direct topographic folklore where land features are explicitly named after him is less common than the general localisation of the narrative to specific areas of the Welsh landscape. The 9th: century version of Englynion y Beddau (The Stanzas of the Graves) gives Bedwyr’s final resting place on Tryfan.

‘Ffynnawn Uetwyr’ (‘Bedwyr’s Spring’): A possible allusion to Bedivere can be found in the 9th: century poem Marwnad Cadwallon ap Cadfan, which mentions a location called ‘Bedwyr’s Spring’. The exact location of this spring is debated by scholars, but its mention highlights the deep, early roots of the character in Welsh topography.

Cei (Kay).

The early Cei and Arthur were often linked to Annwn (the Welsh Otherworld), a realm sometimes perceived as deep within the natural landscape, such as under lakes or mountains. In the tale of Culhwch and Olwen, Kay successfully infiltrates the domain of Wrnach the Giant by posing as a skilled sword-sharpener. He convinces the giant to relinquish his massive sword for ‘polishing’, which is then used in the quest to slay the monstrous boar Twrch Trwyth.

Cynon ap Clydno.

Cynon ap Clydno (or Cynan) was a Welsh Arthurian hero, one of Arthur’s counselors, known for his adventure to the Castle of Maidens, where his encounter with a Black Knight inspired Owain to seek the same quest, setting up the tale of ‘The Lady of the Fountain’. He appears in Welsh tales like the Triads and Y Gododdin, a 6th: century poem, where he is a survivor of the Battle of Catraeth. Cynon represents a key figure in early Welsh Arthurian tradition, with his grave linked to Llanbadarn.

Gawain (Gwalchmai).

‘The grave of Gwalchmai’ is in Peryddon(?). Gwalchmai (or Gwalchmei) is the Welsh name for the legendary Gawain, Arthur’s nephew, known as a fierce and noble warrior, often appearing in Welsh tales as a hero in his own right. His name comes from Welsh elements meaning ‘hawk’ and ‘plain’, reflecting his sharp fighting skills.

‘Tarn Wadling’: A real-world lake (now drained) in Cumbria that appears in The Marriage of Gawain and The Avowing of Arthur, Gawain, Kay and Baldwin of Britain. In folklore, this tarn was considered an ‘explicitly alien’ embodiment of divine power where transfer from the Otherworld was possible.

Llacheu.

Llacheu, also appears to have a traditional burial site. In the perhaps tenth century Ymddiddan Gwyddno Garanhir ac Gwyn fab Nudd we find evidence for the existence of some story of his death: ‘I have been where Llacheu was slain the son of Arthur, awful [/marvellous] in songs when ravens croaked over blood’. The Celtic Sources for the Arthurian Legend, ed. and trans. J.B. Coe and S. Young. Felinfach, 1995. Where this occurred is not stated but we find, in a thirteenth century elegy by Bleddyn Fardd, the statement that ‘Llachau was slain below Llech Ysgar’. Which is identified by some with Crickheath Hill near the Welsh border in Shropshire.

Owein (Yvain).

Tradition often portrays him as the son of King Urien of Gorre and of either the supernatural figure Modron or the sorceress Morgan. In The Dream of Rhonabwy, a Welsh tale associated with the Mabinogion, Owain is one of Arthur’s top warriors who plays a game of chess against him while the Saxons prepare to fight the Battle of Badon. Three times during the game, Owain’s men inform him that Arthur’s squires have been slaughtering his magical ravens, but when Owain protests, Arthur simply responds, ‘Your move’. Then Owain’s ravens retaliate against the squires and Owain does not stop them until Arthur crushes the chess men. The Saxon leaders arrive and ask for a truce of two weeks and the armies move on to Cornwall.

His grave is located at Llanheledd.

Tristan.

‘The Chapel-on-the-Rocks’: At Tintagel, legend tells of ‘Tristan’s Leap’, where the hero escaped captors by jumping through a chapel window down a cliff.

‘The Lovers’ Grotto’: Various versions describe Tristan and Iseult hiding in a cave or grotto while in the forest; a tunnel at Tintagel is often associated with this folklore.

In some Cornish legends, Tristan and Iseult were buried in Cornwall, and a rose tree grew from Iseult’s grave while a vine grew from Tristan’s. The vine wrapped itself around the tree and would grow back even if cut, symbolizing their eternal bond.

‘Tristan Stone’: Located near Castle Dore, this monument has been identified as marking the grave of Tristan.

Artwork © Stewart Guy. 2022.

© Stewart Guy 2026.

.