Experimentalism and Innovation in The Beatles Studio Practice

Experimentalism forms a central thread running through the recorded work of The Beatles and remains fundamental to understanding their cultural and musical significance. While the group is often celebrated for melodic songwriting and mass appeal, their sustained engagement with unconventional sound, recording technique, and compositional process situates them firmly within a broader history of twentieth century musical experimentation. Working in close collaboration with producer George Martin and Abbey Road engineers, The Beatles repeatedly tested the limits of what popular music could contain, both sonically and conceptually.

Experimental practices within The Beatles recordings were not isolated gestures or occasional stylistic flourishes. Instead, they emerged gradually through a process of accumulation, refinement, and increasing confidence. From the earliest years of their recording career, the band demonstrated a willingness to retain sonic accidents and unconventional sounds when they contributed to the emotional or textural impact of a song. This approach reflects a shift in attitude toward the recording studio, not as a neutral space for documentation, but as an active site of creative intervention.

It is important to recognise that musical experimentalism did not originate with The Beatles. Long before their emergence, artists working on the margins of Western art music had begun dismantling traditional ideas of harmony, timbre, and musical structure. One of the earliest and most influential movements was Italian Futurism, particularly the work of Luigi Russolo, which argued that the industrial environment required a new musical language capable of incorporating mechanical noise, urban sound, and sonic abrasion. Russolo’s custom built noise instruments, intonarumori, and performances challenged the assumption that music must be organised around pitch and melody, proposing instead that sound itself could function as compositional material.

This early noise music developed further in other experimental strands. Edgard Varèse explored dense sound masses, percussion, and unconventional timbres, while John Cage destabilised the distinction between music and noise through chance procedures, prepared piano, and environmental sound. Karlheinz Stockhausen expanded these ideas through tape and electronic composition, manipulating spatial placement and nonlinear time. Other early experiments included the noise explorations of Pierre Schaeffer, using recorded environmental sounds and tape splicing, and the electronic manipulations of Daphne Oram with her Oramics system for drawn sound. These experiments provided a rich, albeit largely inaccessible, context for the avant garde ideas that would later influence The Beatles.

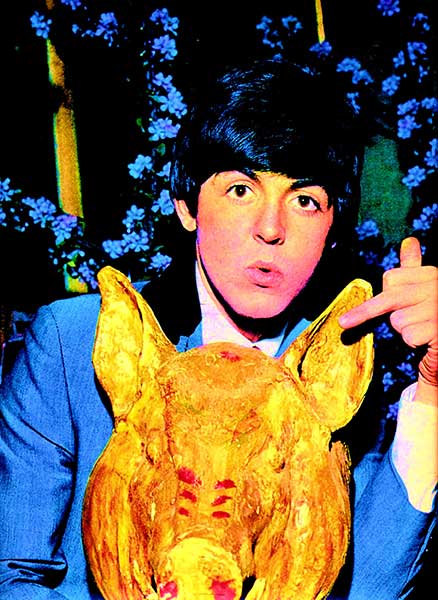

By the middle of the twentieth century, these experimental practices were no longer confined to academic or avant garde circles. Galleries, broadcast recordings, and publications made these ideas available to musicians outside traditional classical music institutions. Paul McCartney’s growing engagement with contemporary art and experimental composition brought these ideas directly into The Beatles creative environment. His interest in avant garde music was practical and intuitive rather than purely theoretical. He recognised that recording technology could be used playfully, unpredictably, and expressively, rather than simply as a means of capture.

Among the members of The Beatles, McCartney frequently acted as a catalyst for experimentation within the studio. When songs were still loosely formed, he often proposed unconventional solutions that challenged established song structures. These suggestions did not always originate from musical necessity, but from curiosity about what might be possible within the recording process itself. This approach contributed to the significant differences often observed between early demos and final album versions.

The gradual emergence of this experimental sensibility can be traced through recordings predating the band’s most overtly experimental work. The use of guitar feedback at the opening of I Feel Fine represents an early instance in which an unintended sound was deliberately retained and foregrounded. Similarly, the dense rhythmic emphasis and production choices on Ticket to Ride subtly disrupt the expected flow of a contemporary pop single. These moments indicate an increasing comfort with destabilising conventional listening expectations.

Revolver represents a decisive stage in this evolution. The album demonstrates a fully developed understanding of the recording studio as an instrument in its own right. Tape manipulation, artificial double tracking, reversed recordings, and unconventional microphone techniques are employed consistently across the album, forming part of its underlying aesthetic logic.

Tomorrow Never Knows exemplifies this approach. Early versions of the song reveal a comparatively direct structure, lacking the dense layering of the final recording. The transformation illustrates the extent to which studio intervention reshaped the composition. The static harmonic framework, relentless rhythmic repetition, and absence of traditional melodic development align the track more closely with drone based and tape music than with standard pop songwriting. The drum performance, recorded with close microphones and heavy compression, produces a forceful and almost mechanical presence that anchors the surrounding sonic activity. Tape loops introduce fragmented vocal and instrumental sounds that resist conventional interpretation, functioning instead as textural elements. The processed vocal further distances the track from familiar pop conventions, reinforcing its hypnotic quality.

Elsewhere on Revolver, experimentation manifests in multiple forms. Eleanor Rigby dispenses entirely with traditional band instrumentation, relying on a string ensemble octet to create a stark, emotionally restrained soundscape. Love You To engages fully with Indian musical structures, including tabla and sitar, moving beyond earlier gestures toward non-Western instrumentation. I’m Only Sleeping employs reversed guitar passages not merely as an effect but as a compositional tool, reinforcing the song’s themes of disorientation. Here, experimentalism functions as both texture and narrative.

Following Revolver, Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band represents a further evolution of the band’s experimental approach, framed around a loose conceptual premise that allowed for heightened studio creativity. The album integrates orchestral arrangements, tape loops, sound effects, and musique concrete techniques alongside conventional rock instrumentation, establishing a fully realised studio aesthetic. Tracks such as Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite employ tape collage and processed wind instruments to generate a carnival-like atmosphere, while A Day in the Life juxtaposes sparse orchestral dissonance with pop melody to create unprecedented structural contrast. Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds blends Mellotron textures, layered vocals, and unconventional chord progressions, producing a dreamlike soundscape that foregrounds sonic experimentation. Within Sgt Pepper, The Beatles demonstrated that experimentation could serve both expressive and conceptual purposes, bridging avant-garde techniques with accessible popular music.

Following Sgt Pepper, The Beatles (White Album) presents a deliberately eclectic and experimental approach. Unlike the cohesive frameworks of Revolver and Sgt Pepper, the album’s diversity reflects both the individual members’ creative autonomy and the increasing fragmentation of their collaboration. The album ranges from stripped down acoustic folk to hard rock extremes, avant garde tape collage, and non traditional sound effects. Revolution 9 exemplifies the band’s most extreme engagement with tape loops, musique concrete techniques, and non musical sounds, creating a sprawling sonic tapestry that draws on Cage, Schaeffer, and Stockhausen. Helter Skelter demonstrates sheer volume, repetition, and aggressive sonic layering, anticipating developments in heavy and punk music. Happiness Is a Warm Gun, Wild Honey Pie, and Glass Onion experiment with abrupt tempo shifts, overlapping textures, vocal layering, and unconventional structures, while Back in the U.S.S.R incorporates playful production techniques and contrasting timbres. The album represents a continued expansion of the band’s experimental vocabulary, pushing boundaries in rhythm, texture, and sonic unpredictability.

Following the white album, Abbey Road demonstrates a sophisticated integration of experimentalism into a more polished and unified production. Abbey Road illustrates a careful combination of classical instrumentation, studio effects, and compositional innovation across a commercial framework. The medley on side two represents a sequence of fragments linked through key relationships, tempo shifts, and harmonic continuity rather than a traditional suite. This approach allowed The Beatles to explore thematic development, musical montage, and tonal contrast within a popular context.

Tracks such as Because illustrate harmonic experimentation, with three layered vocal parts creating a choral texture, while the Moog synthesiser is employed in Maxwells Silver Hammer and I Want You (She’s So Heavy) to generate otherworldly timbres and oscillations. Polyrhythms and tape edits are used creatively in Golden Slumbers and Carry That Weight to manipulate perception of time and pacing, while the extended guitar solo in I Want You (She’s So Heavy) employs feedback and distortion to produce a sense of sonic excess approaching harsh noise music. The album demonstrates that by this point, The Beatles had fully internalised studio practice as a compositional resource.

Experimentalism on Abbey Road is not limited to instrumentation and effects. The band also experimented with texture and production. The crossfading of medley sections, the overlapping of vocal and orchestral layers, and the subtle use of tape compression and EQ reveal an unprecedented understanding of studio technology as a creative tool. Here, experimentation is both musical and technical, reflecting a cumulative process that began with early noise experiments by Russolo, Varèse, Cage, and others, and matured over successive albums.

Individual band members continued experimental work beyond the collective context. George Harrison’s Electronic Sound uses the Moog synthesiser extensively, presenting unstructured sonic textures that mirror electronic and tape experiments in the avant garde. John Lennon explored extended vocal improvisation, noise collage, and minimalist structures, demonstrating that experimentalism extended into post Beatles activity.

In considering The Beatles relationship to experimental music, it becomes evident that their significance lies in mediation and translation. They absorbed techniques developed in avant garde and noise traditions and rendered them accessible within popular forms. Through this process, they expanded the conceptual and practical possibilities of popular music and transformed the recording studio into a space of artistic exploration.

Tomorrow Never Knows occupies a central position within this trajectory. The track crystallises the band’s ability to integrate experimental technique with accessible musical form, serving both as a culmination of earlier practices and a foundation for future innovation. Through sustained engagement with noise, non-traditional instrumentation, studio technology, and structural experimentation, The Beatles established a model of creative exploration that continues to inform musicians, producers, and listeners across genres.

by Ade Rowe

.