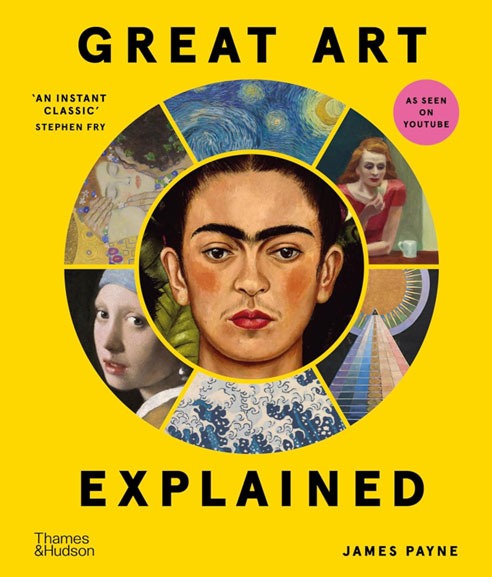

Great Art Explained, James Payne (Thames & Hudson)

Great Art Explained is a video series that aims to demystify art and share the stories that lie behind the world’s greatest paintings and sculptures. Each video has a focus on one piece of art, breaking it down, using clear and concise language free of ‘art-speak’. Great Art Explained the book, has the same aim as the video series and covers some of the same ground, while also expanding the scope of the reflections and extending to artists currently not covered in the video series.

James Payne, founder of the video series and author of the book, has a passion for visual art combined with significant knowledge and the ability to share both in texts that are compelling and concise. Lavishly illustrated and with reference to related artists as well as its chosen artists, the book delivers an introduction to the history of art that is engaging and, on occasions, revelatory.

Payne’s colleague on the Art Cities strand of the video series, Joanne Shurvell, has identified some of the debunking of art myths that Payne engages in the videos and also the book: ‘If you (like most viewers) of Jan van Eyck’s “Arnolfini Portrait” have always assumed the wife is pregnant, you’d be wrong … If you thought Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings depict female sex organs, or that Vincent Van Gogh was mentally ill for most of his life, or “The Scream” is a picture of a man screaming, you’d also be wrong.’ Shurvell has also noted that, in line with Payne’s aim ‘to democratise art appreciation by appealing to a wide audience’, the ‘book isn’t weighted towards white male artists: eight chapters are about female artists and seven are on artists of color’.

The book is not intended as a definitive art history but rather an opportunity to stop and consider the impact of one image, one artwork, at a time. Nevertheless, the choice of artworks is, of course, one of the most interesting aspects of the book and, because the field of art history is so broad, this selection is necessarily partial leaving much scope for follow-on volumes. When a book on great art does not include the likes of Dürer, Giotto, Raphael, Velasquez, Rembrandt, Blake, Constable, Gericault, Cezanne, Matisse, Rothko, Warhol, Gilliam, Bourgeois, Saar, Abramović, Wiley and Gates, the scope for further volumes is made abundantly clear.

Many of Payne’s choices, such as that of Zhang Zeduan, a Chinese artist of the Song Dynasty, as his starting point, are helpfully but challengingly surprising, as also is his decision to jump from the 12th century to the 15th century with nothing in between. My personal preference here would have been to see a Byzantine icon included in order to highlight the principal roots of the Western figurative tradition.

Out of 30 entries, 17 are modern or contemporary. This is an interesting choice of focus as the closer we are in time to art the less confident we can be of its greatness. Art history is littered with artists that were highly regarded in their own time only to find that time has delivered a different verdict on their work. Additionally, and by contrast, several of those that Payne highlights – including Hilma af Klint and Vincent Van Gogh – were almost completely disregarded in the times they lived. The same point made through the reverse experience. So, we have a selection of great art that is not intended to be definitive, simply to begin a conversation, and which challenges more traditional and canonical definitions of ‘great’.

The book itself has three great underpinning ideas. First, while our understanding of art necessarily begins with the artwork itself it is enhanced by the stories that surround it; the intentions of the artist, the context in which it was created and the conversations that have been had about it since. These four factors combine in great art criticism and Payne makes good use of them in these essays, as in his videos, focusing particularly on the artist’s ‘story’, the context of the times and the techniques used to create the work.

Second, artworks create conversation by posing questions to those who view them. In this way, all artworks are interactive. Payne writes that ‘Art is most powerful when it creates dialogue’ and, therefore, his book ‘is meant to be the start of a conversation – not the final word’. Art, he believes, is ‘a dialogue across time’, ‘a living breathing conversation between generations.’ Though separated by continents and millennia, it is this that connects, for example, the contemporary Ghanaian artist El Anatsui with Zeduan, as the works of both are ‘intricate cultural records that celebrate human activity and the passage of time’.

Third, artworks invite contemplation. Payne notes that we live in an era defined by images and where we are inundated with visual content. As a result, he suggests (and this is the guiding principle for his book): ‘We need to stop and consider the impact of one image, one work of art. Art is not just something to look at, it’s something to engage with. It challenges us to pause, to question and to connect with ideas that transcend time and place.’ As he concludes, in writing of Johannes Vermeer’s ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’, art ‘makes us realise that the quiet moments are often the most profound’.

Payne’s intent is to interest and engage through a somewhat non-canonical choice of works and a focus on myth-busting through factually accurate stories. It is an enjoyable and provocative combination that will, hopefully, prove sufficiently engaging to justify further volumes in the series.

.

Jonathan Evens

.