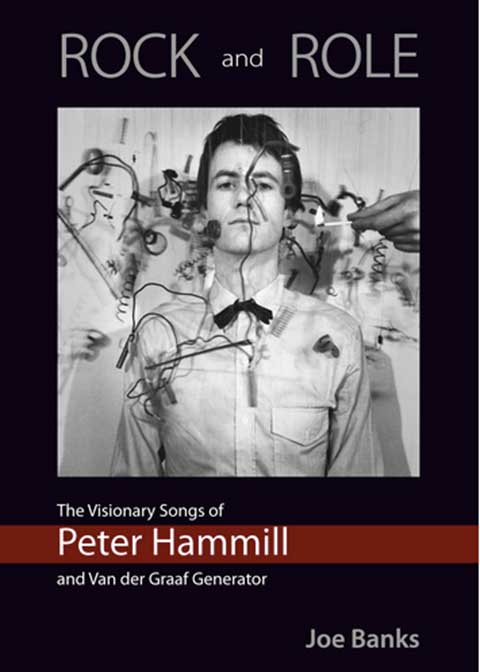

Rock and Role. The Visionary Songs of Peter Hammill and Van der Graaf Generator, Joe Banks (Kingmaker)

Only this morning I was belatedly reading a review of Peter Hammill’s concert last month at London’s Festival Hall, when the postman knocked and delivered the 500+ page block of Joe Banks’ new book. Banks has previously written two brilliant books about Hawkwind but has now turned his attention to the musician and singer the blurb describes as ‘one of music’s most daring and original artists’.

The reviewer was keen to stress how difficult and experimental Hammill’s music is, especially live, which seems to be a recurring comment. Others, such as King Crimson’s Jakko Jakszyk, prefer to focus on Hammill’s supposed confessional writing: ‘If you see him live, it’s insane! He’s just ripping his heart out in front of you’.

Whilst there’s no denying that personal experiences and situations feed into most, if not all, creative expressions, I feel this is a bit over the top. Van der Graaf’s prog outings were just as much about existential angst, mythology and literature as personal experience, and whilst Hammill’s solo albums include the gloriously miserable Over, which agonises over Hammill’s then-recent divorce, other songs focus on politics, apartheid, religion and the nature of time, sometimes in extended suites, sometimes not. Musically, the skronk and squall of VdGG’s take on prog certainly pushed the boundaries of rock as most people know it, but if you were listening to jazz-rock, jazz and improvisation at the time, not just Yes and Genesis, it wasn’t that big a step to take listening-wise. There were lots of science fiction themes, philosophical ruminations and some demented extended pieces such as the side-long ‘A Plague of Lighthouse Keepers’ on Pawn Hearts but they all had a visceral energy to them: Guy Evans’ drums. Hugh Banton’s keyboards and David Jackson’s saxophones soaring under and over Hammill’s keyboards and/or guitar as his vocals weave in and out of the madness may not be for the fainthearted but they were and still are fantastic musical explorations, aided and abetted at times by guests such as Robert Fripp.

Hammill’s solo albums could be more straightforward, almost folk-like in the beginning, but 1974’s In Camera contained the ambient horror soundscape ‘Magog: In Bromide Chambers’ as the creepy coda to ‘Gog’, a mighty heavy rock song with double-tracked drums; 1975’s Nadir’s Big Chance seemed to predict punk with its raw songs of despair and revolution; whilst on 1978’s The Future Now, Hamill was recording stripped back songs on an 8-track recorder that experimented with electronic sounds and drum machines under half-spoken, half-sung rants not a million miles away from the work of Mark E. Smith and The Fall. Hammill was often ahead of the game and was certainly not going to be dismissed as an out-of-date progrocker or hippy.

Van der Graaf’s final incarnation dropped Generator from the band’s name and featured violinist Graham Smith, ex String Driven Thing, in the mix, with Jackson’s saxes only present on two out of the nine short tracks on 1977’s The Quiet Zone/The Pleasure Drone. It’s mostly a blistering album of brief tracks played by a quartet on full throttle, only outdone by the live album Vital from the year after, where the quartet became a quintet or sextet and deconstructed then reassembled old and new songs from group and solo albums. It’s raw, unsettling and – if you’re not in the mood – unlistenable.

I only heard VdGG for the first time well after the Marquee concerts had already been recorded and released, but was fortunate enough to see them several times once they reformed in 2005, following a one-off song by them at the end of a Hammill solo concert. My introduction to the band came courtesy of a secondhand record shop in Harrow, in the back room of a greengrocers! A grumpy dad ran the front shop, his friendly and knowledgeable son was in charge out back. Over the years I frequented the shop, which was near the flat of a friend I worked with as a hospital porter nearby, he would often play and recommend music I had never heard of: Nico’s Desertshore, Roger McGough’s Summer with Monika, and Van der Graaf Generator’s Still Life are ones I remember.

And, because I have always been like that, I soon delved into VdGG’s back catalogue and the albums of their front man, which often featured band members anyway, and also got hold of a book of short stories and lyrics Hammill had published in 1974. Of course, VdGG were not popular in the post-punk circles I mostly moved in, but I later found out that a certain John Lydon, a.k.a. Johnny Rotten, was happy to be known as a fan of Hammill, and that there were many other fans out there.

Joe Banks is clearly one such fan. His book carefully works through ‘all of Peter Hammill’s career’ but ‘focuses on the Charisma years of the 1970s’ and although he says that he has ‘resisted the urge to sieve Hammill’s lyrics for every last meaning and allusion’, he does comment on pertinent themes and sources and notes that ‘however strenuously [a biography] tries to be objectice, it is ultimately a personal account.’ So this is Banks’ take on Hammill. Thankfully, it is intelligent, informed and articulate, with plenty of research, not too much geekery, and very little evidence of the gushing well-meaning fan nonsense that so often mars this kind of book.

Banks’ lucidly and swiftly documents Hammill’s early life and by chapter 2, ‘Pack Your Bags, We’re Leaving Earth’ (all the chapters have tongue-in-cheek pretentious titles like this, which I find quite amusing) Hammill is at Manchester University, hads met up with Judge Smith – a songwriter and musician in beard and cloak – and formed a musical trio. This would later become a quartet, with Smith voluntarily exiting the band (he would remain friends with Hammill) and them being signed to Charisma Records, where they would stay for many years. (See 2021’s box set, The Charisma Years 1970-1978.)

Commercial success pretty much eluded VdGG (although they were big in Italy) and they had a couple of break-ups, although Hammill simply carried on making albums under his own name alongside or inbetween the band’s, often with individual current or previous band members or sometimes the whole lot of them. Early solo albums were mostly more song-based than group albums, but there was a huge crossover, with songs written for the band ending up on solo albums and solo tracks sometimes being pulverised into a new shape live by the band further on in time. The solo albums felt like Hammill outings, whereas VdGG albums would sometimes find his singing buried in the cacophony of musical interaction, despite his ability to scream, yell and pierce the noise with his fantastic vocal range.

Other musicians recognised his ability. The first time I saw Peter Hammill was as a backing singer in Peter Gabriel’s band at the first Womad festival; Hammill was also a guest vocalist on Fripp’s ‘solo’ album Exposure. Fripp has several times told the story of Hammill coming in from the airport to the recording studio in Manhattan, donning a scruffy old dressing gown, grabbing an open bottle of brandy and simply going for it on the full throttle rocker ‘Disengage’ before later chilling out for the soulful ‘Chicago’.

Live, Hammill often played and still plays absolutely solo, with an electric keyboard or a guitar for accompaniment. Here, the bare bones of the songs are allowed to shine, the lyrics to be considered in a different way from their original settings, often juxtaposed with unusual choices from across the impressive body of work Hammill has produced. Other times he has toured with the K Group or with Graham Smith on violin, each tour offering up surprise favourites, choices and sometimes new arrangements. Many of the songs are catchy and moving, but most have enough twists and turns to stop them becoming hummable or chart hits; I’m not sure Hammill would want that anyway…

He is what he is: mercurial, elusive, private and seemingly open-hearted and personal. Banks has, to an extent, penetrated this, chatting to musicians and managers or following clues in sleevenotes and interviews to deduce Hammil’s sources, ideas and both musical and non-musical activities. Quite rightly though, it is the songs Banks comes back to in his book: what is being played, how it is being said and what it is or might be saying. I sometimes disagree with Banks’ interpretations or criticisms, but that doesn’t matter. Banks’ enthusiasm shines through; the book is a labour of love, full of information, ideas and loads and loads of intelligent comments, not to mention photographs. ‘Visionary’ is about right, for Hammill and perhaps for Banks himself. This is the VdGG/Peter Hammill book people like me have been waiting for.

.

Rupert Loydell

.