We are now living in the

post-‘Global Village’ world,

with fragmentation the norm in a

series of parallel bubble-communities

When I first heard mention of the ‘Global Village’ in a 1960s issue of IT: International Times, I admit I held some kind of Science Fiction vision in my teenage head, of some geodesic structure enclosing an experimental community. I was wrong. Marshall McLuhan had coined the term to describe the increasing interconnectedness of the world, as it existed at that time. According to his analysis, first popularised in his 1962 book The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making Of Typographic Man, the world itself was becoming the global village.

I remember ‘Telstar’. I remember watching the first blurry transmission of images broadcast from Andover in the state of Maine, across the wide Atlantic to Goonhilly Downs in Cornwall, on 23 July 1962. The first time that live transmissions were broadcast across hemispheres. A moment as vital, in its way, as the first pictures from the Moon. It was screened on the BBC – because that was one of the only two UK television channels in existence. Appropriately, the Joe Meek-produced single for the Tornados, ‘Telstar’, also proved to be a transatlantic hit record. Because the Telstar communication satellite was a further symptom of the evolving Global Village.

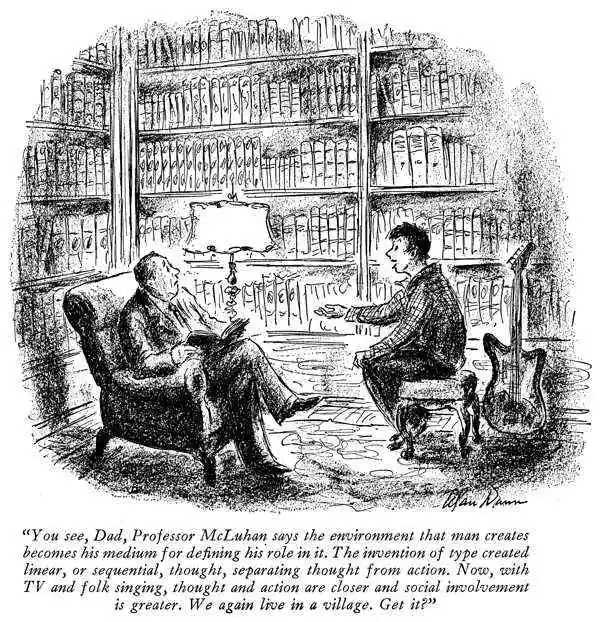

McLuhan’s book traced the phenomenon back to the first proliferation of print – hence the title reference to Johannes Gutenberg who is credited with first using movable type to mass-produce editions of books. The slow spread of literacy that resulted from his invention helped undermine religious certainties and spread ideas which threatened the stability of regimes while subverting supposed doctrinal truths. It made the Enlightenment not only necessary, but inevitable. Yet McLuhan took it further than that. The very structure of print, words that build into sentences. Sentences that build into paragraphs to construct the logical development of a theme, also helps shape human consciousness. We construct dialogue, argument, and philosophy in the same empirical way. It hardwires our thinking. Hence the medium also becomes the message.

At first, time was simply regulated by the chiming of the clock set into the village church steeple, which told the toiler in the field, the blacksmith at the forge, the baker at the oven, the landlord at the tavern door, when to commence and when to take a break. Precision was of less importance. The advent of movies and radio introduced a new era of social connectivity, running in parallel with the increasing universality of print. Bringing a renewed level of immediacy to news, entertainment and information. As well as accelerating the growth of spin-off merchandising industries, taking capitalism into new realms of profit.

By the time of Telstar there was a cultural convergence taking place. Movies had established predominance through a network of cinemas that provide a programme of films; the main feature, supported by a B-picture, a cartoon, an advert break and Movietone News which screened a news-agenda of current events – although they were already days, or weeks old by the time they reached cinemas in the outlying provinces. The small-screen black-&-white Bakelite television set in the front-room corner brought not only a greater news-immediacy but a sense of shared community coherence. With only a duality of TV stations available, the BBC and ITV, popular shows were watched by an audience-share that would seem staggering across subsequent decades. Everybody watched bought-in American Westerns such as ‘Bonanza’, ‘Rawhide’ and ‘The Lone Ranger’, or comedies such as ‘I Love Lucy’. They were as familiar to British viewers as they were coast-to-coast across the American continent. And beyond. Music – a shared teenage passion for Jazz, then Rock ‘n’ Roll, formed another level of shared culture. As the fifties collided into the sixties, it transcended national boundaries and became a global phenomenon.

Yet it was filtered. Television was limited, even in the USA, by a handful of networks. The structure of the music industry, the distribution of physical vinyl product, determined that it was dominated by a small number of powerful record labels. There were Indie moviemakers, but the cost of filming and access to the cinema-circuit meant that the big studios dominated. Books were produced and sold through a tight cartel of publishing houses. They all had a life-support system of critical magazines, who contrived to create a kind of dialogue that defined a cultural mainstream.

The world was divided into two power blocks, defined by their own conceptions of human nature, and by their separate visions of the future. Yet attempts at control across the east were infiltrated by the insidious influence, not of military threat, but by the soft-power seduction of the consumer lifestyle portrayed on TV transmissions, which could be picked up in East Germany, and smuggled in across borders via vinyl records and videocassettes. Through to the collapse of the Soviet Union, when – for a window in time, it seemed as though Free Enterprise capitalism had become a global civilisation. The end of history. The final synthesis of dialectical ideologies. The vindication of Marshall McLuhan’s vision of a wired planet.

Time could be measured to a decimal place. The Moon landing was an achievement of American technology, but it was done for ‘all mankind’. Images from space showed the Earth as a ‘pale blue dot’ that proved the fragile world to be a place without national, religious, racial or ideological divisions. We were humans together in a way that we had never been before, throughout history. Earthlings. In general, corporate media portrayed an acceptance of the differences that had been swallowed up into a liberal uniformity. Capitalism delivered a kind of inclusive equality that Socialism had always promised but failed to achieve, based only on spending power.

Visionary Science Fiction writer Robert Silverberg spun a story, ‘Schwartz Between The Galaxies’ (in Stellar 1 edited by Judy-Lynn del Rey, Ballantine Books, 1974), which caught something of the taste of this increasingly homogenised world. Flying rootlessly from place to place, only to discover that they all look alike, ‘all Earth is a crucible, all gene pools have melted into indistinguishable fluid,’ for an all-purpose new-model hybrid unihuman. ‘Too much of the sameness wherever I go’ he says. International homogeneity. Worldwide uniformity. ‘You go all over the world, you see a thousand syyports a year. Everything the same everywhere. The same clothes, the same slang, the same magazines, the same styles of architecture and décor… in a single century we’ve transformed the planet into one huge sophisticated plastic western industrial state.’

Of course, even the best-run villages have their rundown streets where it’s advisable not to walk alone after nightfall. And the world continued to have its aching trouble spots. While Science Fiction writers such as William Gibson chanced many glimpses into the immersive realm of cyberspace. Few of them got it right. None predicted anything like the shift of consciousness that would result from the next evolution.

TV has become fractured into a multiplicity of platforms, each offering its own beguilement. The shared community of single-vision has been swept away by the deluge, with only unfolding Soaps and appointment-to-view Reality shows providing survival for broadcast television. In a multi-channel environment, the audience has been splintered into factions, each with their own loyalties to ‘The Walking Dead’, ‘Breaking Bad’, ‘Stranger Things’, ‘Game Of Thrones’ and beyond, which seldom overlap, or overlap in different configurations according to selected paid-for platforms.

Cities change in ways they haven’t since the classical times of Greece or Rome. Shoppers used to go to the bakers for bread, to the butchers for meat, to the greengrocers for fruit and vegetables, to the fishmonger for seafood. There are ancient street names such as Butchers Row to indicate that continuity. The first significant shift away was the supermarket trolley, invented in 1937 by Sylvan Goldman, followed by the bland universality of the Shopping Mall. But online purchasing means that city centres have now become a zone of coffee franchises, nail bars, hairdressers and barbers… things that can’t be bought online. But more significant shifts have occurred with the democratisation effect of the internet.

Like the counterculture’s vision of the creator becoming self-sufficient, uncontaminated by grubby commerce, musicians can record their work on the front room laptop and upload it to an instant enclosed audience, generating a word-of-mouth following measured in from tens to hundreds to millions. Hence a bubble-stardom defined by devotees, but totally unknown outside of it. A similar process happened to print-on-demand which removes the literary agent or publisher’s filter and permits everyone to have a shelf of their own books. Monetising such a process can be problematic, resulting in a million voices clamouring for attention, creating a bubble-pack of coexisting micro-continuums. With its own built-in darkness. There are creeps and weirdos out there too. Unpleasant attitudes and anti-social tendencies also find each other. Where once they were isolated, they draw strength by forming an accretion disc of like-minds into a virtual online community that normalises and accepts abhorrent behaviour as a new norm, flaunting sexual, political, religious or racial atrocity. Carried over into the real world in the form of terrorist or gender outrage.

While old loyalties to nation, religion and race persist, increasingly we define ourselves through the virtual community we create by selection, so that there is a multiplicity of parallel zones that simultaneously coexist beneath the surface of the visible, continually shifting and reforming, in a state of constant flux. While, in the same way that print programmed the mind to promote logical thinking, so this state encourages indeterminacy.

Welcome to fragmentation. But in this post-Global Village ecology, the loss of a mainstream culture has more profound results. Social Media encourages dialogue and debate in which each voice carries equal weight. No one opinion is valued above another. That is the nature of its essential democratising shape. Anyone can post. Mischievous conspiracy theory, malicious false-news and political spin are alike currency. Until, through its gradual erosion, truth itself becomes a devalued fluid commodity. There is no longer a consensus truth, only grades of opinion.

There is no centre. There is no authority. There is no mainstream culture. There is no truth. The Global Village has atomised into a continuum of simultaneous villages coexisting in parallel with each other. I’m not suggesting this is a bad thing. I’m not necessarily making value judgement. I’m just saying this is the way it is. This is where we are. We will adjust.

There’s an argument that all attempts at understanding the nature of being is a flimsy skin over existential chaos. Where particle physics and theoretical cosmology are being pushed into conjectures and unknowable conundrums. Where history is subject to interpretation and revision. Yet the scientific method of investigative trial and independent verification underscores the way we understand ourselves and our place in the universe. Which is how we’ve managed to come this far. When truth is reduced to simply one point of view in a plethora of equal relativism, that is a step-change in thinking. That is an alteration of the message, induced by the medium.

That fragmentation is the real legacy of post-McLuhan consciousness.

BY ANDREW DARLINGTON

.