by Ray Foulk

John Sebastian

When Message to Love, directed by Murray Lerner, appeared in 1995, the history of the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival was effectively rewritten overnight. That alone may have been unfortunate. Far worse, however, is the documentary film’s long-term impact: it single-handedly seeded a false narrative about the collapse of the 1960s counterculture itself. Over the decades since the film’s release, a steady stream of other documentaries, compounding with lazy journalism, books, and articles, have drawn heavily on Lerner’s version of events as if a primary historical source (which film can be until cut, edited, and reordered), using the 1970 festival as the definitive case study in how the counterculture supposedly imploded. This, by his own admission, was Lerner’s mission – but it was misguided and reprehensible.

When Message to Love, directed by Murray Lerner, appeared in 1995, the history of the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival was effectively rewritten overnight. That alone may have been unfortunate. Far worse, however, is the documentary film’s long-term impact: it single-handedly seeded a false narrative about the collapse of the 1960s counterculture itself. Over the decades since the film’s release, a steady stream of other documentaries, compounding with lazy journalism, books, and articles, have drawn heavily on Lerner’s version of events as if a primary historical source (which film can be until cut, edited, and reordered), using the 1970 festival as the definitive case study in how the counterculture supposedly imploded. This, by his own admission, was Lerner’s mission – but it was misguided and reprehensible.

The director crafted a story in which the counterculture ends not with reflection or transformation, but with conflict, chaos, and hypocrisy. He promoted the film as evidence that the festival was a microcosm of the wider youth movement: what went wrong on the Isle of Wight, he suggested, was what went wrong everywhere. But a close examination at the footage – his own footage – confirms almost the opposite. If the counterculture was fading, it was doing so more through apathy, drift, and a turn toward fashion, rather than through conflict and rupture. This is a far more mundane, but far more plausible, explanation than the melodramatic downfall depicted in the film.

While there was some unrest at the festival, in scale it was, to borrow a phrase, no more than a fleabite on the side of an elephant. Most of the trouble occurred before the event even began, when organisers were attempting to block access to the adjacent hillside offering a free view of the stage. During the event itself, the increasingly histrionic outbursts from the compere were regrettable, but they had little bearing on the multitude inside the arena or on the peaceful – even if unpaying – spectators on the hillside. A tiny group of radicals made several insignificant attempts to breach the arena fence. From these isolated moments, Lerner was able to find enough material to stitch together, in the edit, something far more ominous than the reality – sufficient to trash the event. Meanwhile, the narrative even flies in the face of the official record, as exemplified by evidence given by Sir Douglas Osmond, Chief Constable, Hampshire Constabulary to the subsequent government enquiry. He had attended incognito and claimed to see less violence than at a typical football match. He concluded:

“People become unduly anxious about these gatherings … The world’s press was present in considerable numbers. They sought sensation but in the main were disappointed …By the end of the festival the press representatives became almost desperate for material, and they seemed a little disappointed that the patrons had been so well behaved”. Quoted Michael Clarke, The Politics of Pop Festivals, Junction Books, 1982.

We might add that Lerner was similarly desperate for dramatic effect. As Message to Love unfolds, the viewer is subjected to extreme exaggeration of relatively minor, occasional conflict. The editing contrived to generate excitement for dramatic purposes, if not as part of a spiteful revenge on the part of a director (apparently wounded by his dispute with the festival organisers) to simply trash the event. Examples of such disreputable practice are not only peppered throughout the film but dominate it, notwithstanding some excellent footage of music performances.

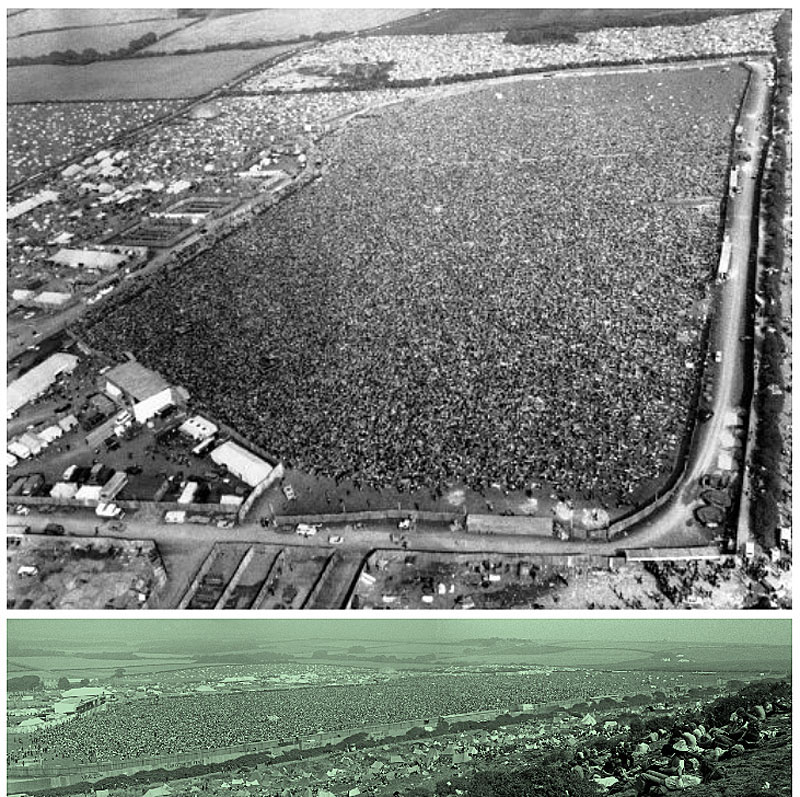

Isle of Wight Festival of Music, August 1970. These photos taken on the fifth day do not show an event of unruly behaviour,

with the two miles of walling 100% intact, with security/vehicle routes clearly maintained.

The tabloid and right-wing press of the time, true to form, predictably amplified the limited instances of conflict. Yet subsequently, this did not endure as the dominant narrative: the broadsheets, magazines, and music press, were generally far more measured – at least until Message to Love appeared in 1995. Since then, however, the film’s account has been repeated so often that a gloomy mythology has hardened into “fact”: that the counterculture died in an episode of anger and confusion at the Isle of Wight. This story persists despite its distance from the lived reality of the festival and from the spirit of a movement that – however idealistic or naïve – genuinely sought a kinder, more humane world. To recast that history as a tale of disintegration and betrayal is not only inaccurate; it besmirches a generation of young people.

While the counterculture categorically did not come to a disruptive end at the Isle of Wight, or anywhere else for that matter, the swift decline in the early seventies cannot be separated from the change in music tastes. The 1960s movement was shaped in no small part by artists and the music which came to embody it. By mid-decade, a new form of popular music had emerged – distinct from early Rock & Roll and more substantial than mainstream Pop. This evolving sound fused electrified instrumentation with lyrical themes drawn in the manner of Folk and Blues traditions. It resulted in what could fairly be called issue-based repertoire: songs that confronted grievances, questioned authority, and imagined a more just and humane world, and to some extent held the counterculture together, if not leading it.

Protest music, once a niche, entered the mainstream with striking speed. Bob Dylan was central to this shift; albums such as The Times They Are A-Changin’ produced chart-topping songs that articulated generational unease. His electrified performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival marked a pivotal moment, signalling that acoustic protest songs were giving way to a new wave of electrified, politically conscious Rock.

As the Vietnam War escalated, this music became a binding cultural force, helping to unify what is also known as the Hippy Generation. Across the United States – and soon in Britain and Europe – millions of young people embraced the era’s lyrics not simply as entertainment, but as social commentary. Issue-driven rock evolved into the defining soundtrack of a generation newly aware, newly vocal, and increasingly ready to question the world it had inherited. Many later viewed the movement’s cultural peak as having been reached at America’s Woodstock Festival in August 1969, and, arguably, a year later at the Isle of Wight.

Jimi Hendrix

Rory Gallagher and Taste

Joni Mitchell

Tiny Tim

.

There were, of course, radical elements among the many tribes that made up the counterculture. In the post-1970 period a small rump of extremism lingered, most visibly in the emergent “free” festival movement, where attempts to hold illegal events in Windsor Great Park and at Stonehenge, often ended in fights with police. But these involved the tiniest minority. For most young people, the broader youth culture across the population simply drifted back toward non-political popular music – still labelled “rock,” but no longer anchored to issues and the people’s preoccupation with challenging the status quo. Ideas of “dropping out” faded remarkably quickly.

Contrary to the Message to Love narrative, the counterculture’s decline coincided with – or even driven by – this marked shift in musical taste as many leading artists embraced the emergent styles of early 1970s Glam Rock – think David Bowie, Slade, Gary Glitter, or Emerson, Lake & Palmer. Whether musicians steered this cultural turn or were responding to changing youth preferences is ultimately immaterial here. What matters is that the counterculture did not collapse through conflict or ideological fracture but rather faded through apathy and a peaceful realignment of tastes and market forces. Its end was not a rupture, but a quiet and benign transformation.

The vast audience gathered on the small island off England’s south coast in 1970 was not only peaceful but, at times, almost too subdued. It is worth repeating that the much-discussed “conflict” stemmed from a tiny minority outside the festival arena. Across the three Isle of Wight festivals, only one performer was ever booed off stage – and even he returned a few days later to a warm reception. Kris Kristofferson’s difficulties stemmed largely from a single, badly misunderstood song, Blame It on the Stones, which some assumed was an attack on the audience’s beloved Rolling Stones. Stung by the experience, Kristofferson later seized every opportunity to disparage the festival, not least in interviews that appear in several of Lerner’s films, where he offered sweeping and inaccurate claims such as “all the artists at the Isle of Wight had a bad time,” projecting his own misfortune onto everyone else. These distortions have since been repeated endlessly in articles and online commentary. In fact, almost every performer in 1970 returned to the stage for enthusiastic encores. Kristofferson’s most far-fetched assertion – that Leonard Cohen alone “tamed the beast” – is similarly contradicted by the Lerner’s own footage. Cohen’s set, delivered at four in the morning, was not the vanquishing of a hostile crowd but a masterclass in gently awakening an audience that was, by then, sleeping or simply exhausted.

As the festival’s history has been gradually rewritten, Joni Mitchell is the other performer whose appearance has become mired in controversy. Her otherwise superb set was interrupted twice: first when someone collapsed near the front of the stage and required medical attention, and again when an acquaintance of hers stumbled onstage under the mistaken belief that he had permission to join her. The audience immediately in front responded with boos as the intoxicated intruder was removed. Lerner exploited the moment in his film, intercutting a heated backstage argument – audible neither to Mitchell nor to the crowd – with her performance to imply that the incident continued to unsettle her. In reality, the consummate professional returned for two encores, and Melody Maker celebrated her performance on its front page under the headline “Joni’s Triumph.”

Journalists and producers would do well to examine the footage more carefully and consult authoritative sources – instead of unthinkingly perpetuating Lerner’s manipulated version of events. When inaccuracies are repeated often enough, they distort cultural memory, in this case leaving future generations with a profoundly mistaken understanding of how the sixties counterculture came to an end.

Ray Foulk, co-promoter of the Isle of Wight Festival, 1968-1970.

Ray Foulk, co-promoter of the Isle of Wight Festival, 1968-1970.

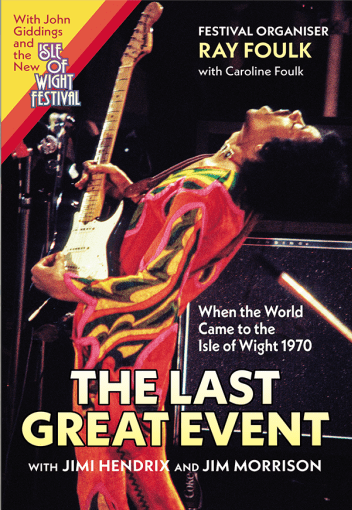

Author of Stealing Dylan from Woodstock, and The Last Great Event, Medina Publishing, 2015 and 2016 (revised paperback 2025).

.

.

Well said Ray – Lerner may have been put up for this. The globalist influence was getting anxious about the unison created by these mellow and thoughtful times. Your efforts to bring that concert was a response to the feelings of millions of awakening souls. But the 70’s brought ‘the music industry’ and the start of the grand distortion we see now.

Best wishes. Julian

Comment by Julian on 20 December, 2025 at 8:56 am