After the Great War Germany was in chaos, it was an inferno of extremes.

Eventually the Weimar Republic gave some social stability. But the interwar period was to see not only a new wave of artistic innovation, but also the inexorable rise of the Radical Right. New art movements included the Italian Pittura Metafisica (1917) of De Chirico and Carra, the Dada movement (founded in Zurich in 1917; Berlin, 1918; Cologne, 1919), Surrealism (1924) and Constructivism (1920). During the ensuing period (between 1920 and 1938) the spread of dictatorships was so rapid that, by 1939, there were only twelve democratically elected governments in the whole of Europe. Inspired partly by the example of D’Annunzio’s Arditi Mussolini marched on Rome to seize power in 1922. Numerous other European states fell under the sway of right wing regimes: Bulgaria (1923), Spain (1923), Turkey (1923), Albania (1925), Portugal (1926), Poland (1926), Lithuania (1926) and Yugoslavia (1929). The process continued into the 1930s with the rise of further dictatorships: King Carol II (Rumania, 1930), Salazar (Portugal, 1932) Hitler (Germany, 1933), Dolfuss (Austria, 1933), Metaxas (Greece, 1936) and Franco (Spain, 1936). As has been mentioned the rootlessness and alienation of intellectuals corresponded to the turbulence of the times. Like Barres and Celine in France a number of fin-de-siecle personalities became entangled in the politics of the radical right. Others like the Dadaists and the Surrealists attempted to work actively with Communists and other left-wing anti-Fascist groupings. D’Annunzio’s League of Fiume (‘Regency of Camaro’) has been cited as a typical forerunner of the fascist state, with its Leader Cult, ritual oaths, insignia, militarism and a barley, articulated ideology that blurred the boundaries between politics and religion in ‘mass manipulation by myth and symbol’ (O’Sullivan). Apart from D’Annurizio, the case of Ezra Pound’s fascination with Mussolini is too well known to need further comment here. As also is W. B. Yeats’ slight involvement with the Irish Blue Shirts movement of General O’Duffy in 1933. Although conditioned by his occult chronology A Vision (1925-37) to flirt with visions of elite government, Yeats soon asserted an apolitical detachment: ‘What if Church and State/Are the mob that howls at the door:’ he wrote in 1938. In England the former Vorticist and agent provocateur of Imagism Wyndham Lewis wrote a series of books Hitler (1931), Left Wings over Europe (1936) and Count Your Dead: They are Alive (1931), which led to his ostracism by pragmatic working class intellectuals and turned him into ‘the most hated writer in Britain’ (Julian Symons). Lewis never recovered from this stigma. In Germany itself the Expressionists continued to adopt a visionary stance although historians have denigrated their naivete: From the working class, whom they tended to idealise and patronize and to whom they offered themselves as leaders… their mixture of anarchism and utopianism elicited no response. Craig, Gordon A, Germany 1866-1945, Oxford University Press, 1981

For historians like Craig, the alienation of the Expressionists in the stabilized Weimar Republic was one factor in the rise of Nazism. For the Expressionists and the Dadaists (who regarded themselves as more radical) the Republic of the 1920s simply perpetuated the pre-war evils of bourgeois ethics, Wilhelmine Militarism, bureaucracy and general banality. For the dissolute and well-healed on the other hand, the ‘Jazz Age’ and the razz-ma-tazz of ‘The Roaring Twenties’ had arrived -it was another period of Decadence; the hedonistic era of flappers such as Clara ‘the IT Girl’ Bow and Colleen Moore.

Nevertheless, in the 1920s Expressionism continued to provide the impetus for innovation despite the rise of other movements like the neo-Naturalist Neue Sachlichkiet. Many Expressionists turned to drama and wrote plays about wartime experiences, pioneering radical styles of dramatic production. For example Reinhold Goering’s play Seeschlacht (1918) was written in a sanatorium after the author had been invalided out of the army. Seeschlacht (Sea Battle) was a picture of the Battle of Jutland as experienced by sailors in a single gun turret. They speak in stylized verses, fight blindly in their prison-turret and recount memories and visions. Between 1916 and 1918, a series of Expressionist dramas were staged under the collective banner of Das Junge Deutschland. In many cases the general public was excluded from the performances. George Kaiser (1878-1945) wrote experimental dramas called Denkspiele (Thought Plays). Influenced by Strindberg and Wedekind, Kaiser used impersonal, allegorical characters, crowds organised into formless masses, animated machines and symbols of power. He incorporated the concept of geist into the plays as an actual protagonist, as in his Gas Trilogy: Gas I (1919), Die Kalle (1917) and Gas II (1920). Kaiser took the desolation of Kafka and projected it onto the horrors of modern industrialization. The worker is depicted as a faceless automaton, ground down by impersonal forces. This is the world later depicted by Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou in the pioneer SF film Metropolis (1926).

Perhaps the most forceful of these pioneer dramatists was Ernst Toller (1893-1939). He volunteered for the front in 1914, but, having been discharged for medical reasons, became an active pacifist. During the revolutions of 1918 Toller played a leading role in the ill-fated Bavarian Soviet, working as secretary to the premier Kurt Eisner. Eisner was assassinated and the Bavarian enclave was obliterated by a right wing private army under General Von Epp. Toller was sentenced to 5 years imprisonment for high treason. Released in 1924 he fled to America in 1932. Eventually he committed suicide in a New York hotel room in 1939. His most interesting writing was done in prison: Das Schwalbenbuch (Prison Poems) (1923), the plays Masse Mensch (Mass Man) (1920) and Die Machinensturmer (The Machine Wreckers) (1922). Masse Mensch was a nihilistic vision of sociopolitical despair with symbolic characters. The masses seize power led by an idealistic girl social worker. The workers demand the total destruction of the state, the woman abandons them but is executed by the authorities. The workers, meanwhile, attempt to destroy the state in an orgy of violence but they are eventually crushed.

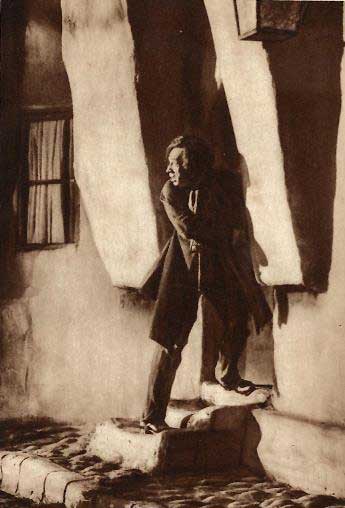

Many Expressionist themes were embodied in the films of the Weimar era. These movies translated the demonic and the Gothic elements of the Expressionist tradition into works which have been extremely influential for both the mainstream commercial cinema and the later ‘underground’ tradition of subjective ‘film-poem’ experiment. Actors like Conrad Veldt, Emil Jennings Werner Krauss and Paul Wegener all began in the Expressionist theatre and carried the Expressionist acting style onto the screen in early horror films like The Student of Prague (1913), (script by fantasy writer Hans Heinz Ewers), Der Golem (two versions, 1914 and 1920) after Meyrink and the legends of the Jewish ghetto in Prague, the six-part serial Homunculus (1916), and Das Kabinet des Dr Caligari (1919). Caligari in particular has achieved historic significance because of its distortional sets and supercharged performances from Conrad Veldt and Werner Kraus as the evil doctor and his lethal somnambulist. Throughout the 1920s directors like Fritz Lang, Henrik Galeen, G.W. Pabst, Arthur Von Gerlach, F. W. Murnau and others made a string of films in the demonic-Gothic style, often using original works by Expressionist writers – like Georg Kaiser’s Von Morgens bis Mitternachts (1920) or Alfred Doblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz (1931), a monumental exercise in sordid naturalism. G.W. Pabst directed Wedekind’s Pandora’s Box with Louise Brooks in the leading role (1928). Other films of interest to the present discussion are Fritz Lang’s two-part version of Die Nibelungen with symbolist Jugendstil sets evoking the world of Arnold Bocklin, and horror films like Paul Leni’s Waxworks (1924), Robert Weine’s Orlacs Hande (1924), F. W. Murnau’s Faust (1926) and his version of the Dracula story Nosferatu, eine symphonie des Grauens. (1922).

These films of the period have since become classics and also represent a continuity of the themes of Decadent-Symbolist horror that can be traced back to Romanticism and even earlier cultural periods. The ‘German Look’ in terms of lighting and camera work became encoded into the cinematic tradition of dark horror, suspense and noir style crime drama (in the work of Hitchcock and others) in the post-war era and still highly influential today.

This can be contrasted with Jazz-Era American films from the period in which Decadence in terms of hedonism was portrayed in a more-or-less frivolous, fashionable manner; in ‘youth’ films such as The House of Youth (1924), The Perfect Flapper (1924), The Mad Whirl (1925), Our Dancing Daughters and Mad Hour (1928). This was the world of Scott Fitzgerald, Cole Porter and the ‘designer decadence’ of Art Deco. The stereotyped idea of Roman Decadence was used in ‘morality films’ like De Mille’s Manslaughter (1922) where the follies of sensation-seeking youth are compared, in lavish flashbacks, to the depravities of a dissolute Roman Empire (‘The Goths are coming!’) just before its fall. During the war years American movies had appropriated many of the trappings of European Decadence. Decadent sexuality was the stock-in-trade of Vamps (femmes-fatales) like Valeska Suratt and Louise Glaum. The most notorius Vamp was Theda Bara (Theodosia Goodman) who played both Cleopatra and Salome in 1918.

Occult movements thrived in the years before the Nazi takeover. Whereas in the early nineteenth century occultism was aligned to politics of the left, in the twenties and thirties European occultism was part of a complex patchwork of visionary nationalism. In the chaos bizarre hybrids were spawned, like Karl Radek’s National Bolshevism (1919) or the doctrines of Arthur Moeller van den Bruck (1876-1925) who tried to forge links between an ‘New Age’ ideology of a spiritually reformed Germany and pan-Slavic idealism. His reformed Germany was to be called a Third Reich in imitation of Joachim of Flora’s Third Age. His book The Third Reich was published in 1923. He also collaborated with the Russian Symbolist Dmitri Merezhovsky on the first complete German translation of Dostoyevsky.

.

A C EVANS

Illustration: The Student of Prague, 1913. (dir. Stellan Rye)

.