When I started working at the Record & Tape Exchange in 1985, the epicentre of that pre-owned retail empire was a 200 yard stretch of Notting Hill Gate, containing three branches, with a fourth just around the corner in Pembridge Road. Then there was an outpost in Camden – opposite the market – and another in Goldhawk Road, Shepherd’s Bush.

Thriving in that environment was not just about how well you worked or what you knew. Liking the right records counted for at least as much. More, probably. There was a moment in everybody’s time there when they got to put on a cassette to play over the shop hi fi. A privilege jealously guarded and grudgingly handed out by whoever the most senior person was in the shop that day. This was a rite of passage fraught with danger. I saw careers end on that first cassette choice. When my time came I chose the Buzzcocks debut album. Who could possibly complain? Paddy, the senior man that day, muttered ‘playing safe’ under his breath. But I survived.

Negotiating the prevailing cultural conventions was no easy task. At the time I was discovering the likes of Tom Rush and Tim Hardin. Fortunately, this went down well. I once put on ‘The Circle Game’ by Rush and my colleague that day, Dick – a taciturn, ponytailed veteran in his 40s – said ‘Mm. I heard there was a new Tom Rush fan’, his stony features cracking momentarily into an expression not too far from avuncular fondness.

A friend, Gary, who started at the same time as me liked Julian Cope, but this – surprisingly, it now seems – wasn’t right at all. Gary didn’t last. The Cramps were right, though. And Dion. And The Sonics and The Saints. Leonard Cohen? No. Nico? Yes. Kris Kristofferson’s Jesus Was A Capricorn? Yes. Scott Walker? Yes. The Blue Nile? Not really. U2? I ask you.

Also, there was status attached to which shop you worked in. Getting sent to Goldhawk Road wasn’t quite like getting sent to Siberia, but it wasn’t far off. Usually there’d just be two of you there, and the place was quiet. You could sit for hours on a weekday afternoon listening to the Cramps or Dion without any customers coming in. There, as in all the shops, only the sleeves of most of the albums were out on display. If you wanted to buy one you bought the sleeve to the counter and a label with a code on it guided the sales assistant to the record itself. Filed in its inner sleeve somewhere in a labyrinthine shelving system behind the counter. Cheaper records were out on display, though. These attracted no-goods who would attempt to walk out with armfuls and peel the price labels off, once out of range. Later, they’d bring the same records back and try to sell them to you. A ruse commendable for its audacity, but rarely successful.

The Goldhawk Road shop was terrorised by a character we called Goldtooth. A cut above, or below, the usual class of petty criminal we dealt with. He was known to threaten violence and demand money from the till. To counter this, a mild-mannered security guard was employed, a benign uniformed presence who hovered around the premises all day. He was allowed to ask Goldtooth to leave, and to phone the police, but had neither the natural authority nor the heft to eject him. His presence was entirely ineffectual. There were times when Goldtooth came in and took what he thought he deserved while staff and security guard stood around watching, waiting for the police to turn up.

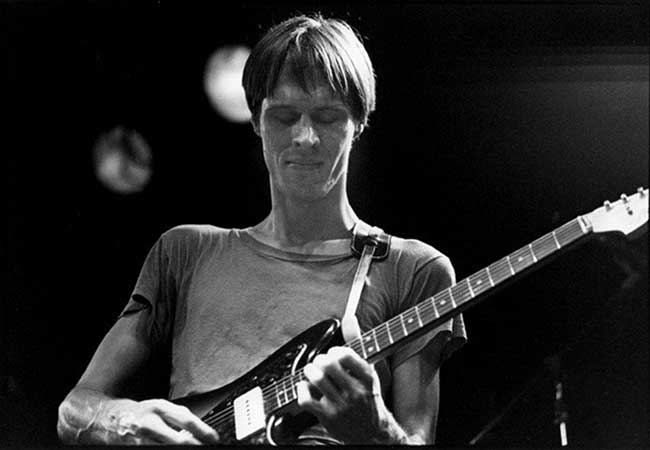

I started to think about all of this again when I heard of Tom Verlaine’s passing in 2023. For a while I was second in command in the books department. I took care of the place when the manager, Andy, wasn’t working. It was on the first floor, above the musical equipment and musical instrument department in Notting Hill Gate. Brian Eno was a regular browser downstairs. Upstairs we had Mick Jones, of the Clash, and Tom Verlaine of Television. At the time Verlaine was living in London, possibly nearby, as he was in the shop pretty often. He looked exactly how you want your heroes to look. Tall, upright. Elegant neck and cheekbones. Always wearing a long dark coat. Scrutinizing the poetry shelves. Sometimes buying a volume or two. Maybe asking ‘do you ever see anything by …?’ or suchlike.

Once Verlaine was in the shop and a regular troublemaker came in. Not in Goldtooth’s league, but someone with a permanent grievance, who would harangue you about an over-priced book or some other perceived injustice. He had a go at me for a while them stomped down the stairs. Verlaine turned to me and said ‘we’ve got people like that in New York’, then came to the counter with a book to buy. I took the money and rang it up on the till, then asked him what he was working on.

I knew almost as soon as the words left my mouth that I had made a mistake. Innocently yet unwisely I had crossed an unseen boundary. I had assumed a familiarity that just wasn’t there. Verlaine broke off eye contact, mumbled something vague and evasive, and blushed. I don’t recall now if I saw him again in the shop, but I left not long after.

About 15 years later a music magazine sent me to interview Television’s other guitarist, Richard Lloyd. By coincidence, this took place in the dining room of a hotel in Notting Hill, just down the road from the book shop. It was a perfunctory meeting. I was one of several journalists wheeled in that afternoon. Lloyd was polite, helpful and obviously bored. I don’t blame him. For me the best thing about the occasion was that he wore a red Harrington-style jacket, just like the one he wore on the cover of Television’s second album, Adventure. It was only when I sat down to write this that I twigged that I met – fleetingly, in Notting Hill – both guitarists responsible for some of the greatest guitar music ever made. To be face to face with a world so alive.

.

Mark Brend

.

According to Richard Hell’s interesting autobiography TV frequented bookstores all his life. The two of them first bonded over books and poetry and iirc your faux pas chimes with RH’s commentary.

Comment by Philip Lees on 27 January, 2026 at 10:16 am