Silent Hundred Gouache, Oil Pastel, & Oil 56.7 x 75.9 cm, 1999

From more than forty-five years ago, I can clearly see Rushbeds Wood[i] in North Buckinghamshire: the gently rising track through trees, the leafy railway cutting, the short tunnel. All in deep country, mid-morning, sunny summer, quiet but for birdsong.

Isolated amongst a network of lanes that can barely have changed since they were tarmacked, through landscape barely disturbed since Edwardian days . . . memory effortlessly displaces reality.

Whether it is still that way I can’t say. I haven’t been back. That this was almost the Ultima Thule of Metroland[ii], I didn’t know at the time, though I had noticed the remnants of an old railway bridge here before [iii].

The noise of the Roman road[iv] had long been left behind, along with the Crooked Billet, a sinister looking pub repressed amongst conspiring branches. A pub that I never went in, not even when I was older[v]. By contrast, the woods here and to the west, uphill, are friendly and the sense of a necessary present has diminished. Here, it is anytime and every time. The handlebars of my bike shine accordingly.

Then comes the sound of a slow lorry. In the distance from the trees and back into the trees, it crosses another bridge over the railway, a huge hollow box with bold lettering, a removal van bobbing its way on up the hill towards Brill perhaps. Briefly evocative of changing lives, of somebody coming or going.

Occasionally in the late 70s, a few years on from above, I worked for a removal company. A friend of mine in Princes Risborough who toiled for them full-time would call me when they needed an extra lifter. Suburban terraces and quiet, church close residents alike, never came to dread Whiteleaf Removals[vi] as perhaps they ought? With their long liquid lunches and farcical corner cutting, Whiteleaf Removals were the company that inspired me to always do my own house moving. There’s a difference between disconnection and disintegration!

Had living in a printed-out place, enhanced Alun’s awareness of hidden values? In some obscure way, he felt as though he were in transition – a change more fundamental yet more abstract than the social one his father appeared to regret. Assuming this wasn’t just imaginative fantasy, would such a transition have been impossible without his family’s recent history of geographical dislocation, his own free growth among paper surroundings?

An inviolable calm surrounded the idea of disconnecting from history. He was no longer worried. The old life felt trivial and he needed space to think. Or at least space without regulation. If he could only spend time with the meanings between words or within the freedom of music . . . or live near some rocky shore – the sea being symbol of a world that could not be mapped.[vii]

Perhaps such portentous fantasies were ridiculous; but for now, it was best to gently believe in them.[viii]

Home is clearly a transient thing; an illusion we understandably cling to. To quote Paul Tillich[ix]: Man is a fragment and a riddle to himself. The more he experiences and knows that fact, the more he is really man. [Saint] Paul experienced the breakdown of a system of life and thought which he believed to be a whole, a perfect truth without riddle or gaps. He then found himself buried under the pieces of his knowledge and his morals. But Paul never tried again to build up a new, comfortable house out of the pieces. He dwelt with the pieces[x]. He realised that fragments remain fragments, even if one attempts to re-organise them. The unity to which they belong lies beyond them; it is grasped through hope but not face-to-face.

Now, forty-five years after working for Whiteleaf Removals, their ethos had struck again, 217 miles north, near Fleetwood in Lancashire. The old 70s team of Francis (lushly drunk or tortuously indecisive), Oakham (too vertically challenged to see over hoisted furniture, contentedly packing china while telling us “boys” how we should be lifting) and Denny (crippled by a bad limp and a weak bladder) were replaced by X (circular beard and spindly legs) Y (mute but smiling) and Z (hair-tearing chief, loader and driver, restraining his despair). How the parallels threw me back . . . despite that in both cases, I was lucky to be at one remove: temporary worker in the late 1970s; back-up and driver in 2019.

Yet, as time went on, the house of my son’s family looked less like it had been hit by Christmas or an infernal tornado. It appeared, in fact, that chief Z accurately had the measure of things. He could see the future. He knew what would fit where. Their undersized removal van had Tardis-like properties we had not suspected. The memory of Whiteleaf Removals was eclipsed and left on the hard shoulder.

Anchorsholme Promenade, near Cleveleys, Lancashire, 20th June 2025

After Chief Z and co. had departed, we checked, cleaned and tidied before setting off to roughly echo the removal van’s route. Immediately snarled in traffic, a digression became essential: to grab a pair of sunglasses in Poundland, for the sun was in my eyes in a manner not ideal for driving . . . Wishing to lose the distant sight or influence of Blackpool’s tower, I recognised in someone else’s journey between two lives, the process I’d been through the year before and would go through again a year later. Not that lives change so much perhaps if you shift only locally, but over a hundred miles they must, however many constants survive. Children and partners may lessen the impact. Belongings and a hopeful sense of escape may lessen the impact; yet whatever the positives and the distractions, one period has clearly ended and a new one begun.

To be forced to move to escape persecution or the violence of war, is an unimaginable extreme for most of those living in the relatively settled United Kingdom. Regardless of the slow diminution of society around the globe and the alarming rightward tilt occurring generally it seems, so far, most of us remain expert at keep our eyes firmly shut and our aspirational desires focussed.

We also, understandably, crave comfort, settledness and familiarity – all the things the word home represents: the heart, the hearth and so on . . . the gatherings in winter darkness at Christmas. But is disconnection from home a poverty, or can it be an opportunity? If memories change every time we entertain them, in what way do they differ from imagination? Is home only a distraction – as animal desires are seen by some as a distraction from the metaphysical. Is home a distraction from escape?

Have I given up on the idea of home?

to live in some eternal motion of impressions

a self-sealing, personal corbomite[xi]

I’m aware that where I now live is not somewhere I ever wanted to be. I have adapted to it, yet constantly dwell on designs for escape. An escape towards the dream of the lodge; to remote and more elemental landscapes; even to papery, duplicated suburbs elsewhere – any elsewhere. In reality, my greatest escapes now, arise either through a expanding propensity to see the visionary in the ordinary, and/or an increasing ability to feel life as if it were an evolving experiment in improvised music – a symphony without musicians, aimed towards the metaphysical. In these necessarily temporary states of mind, home becomes almost an irrelevance.

Memory is notorious for revising the supposed actual, for cutting out the general tedium, yet always tends to remember the nightmare or temporary paradise. Regarding the journey from Fleetwood to London, I remember the clogging chain of traffic crawling past Preston before memory shifts to the M6 toll road south of Birmingham. Suddenly, the road felt as empty and free as Rushbeds Wood in the 1970s – if open, rectilinear and overexposed rather than green, fluid and enigmatic. Red deer on the hard shoulder gave the impression that the world had recently been emptied . . . just as a small aeroplane with target markings, droning over a North Buckinghamshire wood in the late 70s, (Romer Wood near Botolph Claydon on that lost occasion), had projected an acute sense of absent war – as if it that plane had flown in, not just from a faraway zone of conflict, but from another era altogether. For a while, anyone might have expected the sound of sirens to follow it . . . but as it faded, its memory and what it stood for, acted as a contrast, emphasising the leafy tranquillity of the woods. For a period, it was even more than that. For a while, the open woods eclipsed the security of all internal homes – their safety was both oak and clouds, solid yet ethereal . . .

Back in 2019, we reached the Dartford crossing very late, partly to avoid that particular toll – not charged between 10pm and 6am. Plumstead’s night, half an hour later, appeared to embrace the coolest point of a heatwave:

Plumstead night, August 1st 2019

All this was 6 years ago now, and at the time I’d not long listened to Mark Fisher’s 2014 lecture around the “slow cancellation of the future”[xii]. A challenging if depressing idea, the slow cancellation of the future has almost certainly been emphasised in a morbid celebrity-worship culture, by Fisher’s suicide. For all its undoubted value however, the dread behind such an idea of cancellation (whether applied to music or more widely to politics and society) at least to my impatient mind, cannot also help but raise the spectre of the static-academic: that desk-bound sadness likely to infect anyone vocationally obliged to spend too much time with words – or more particularly, the often-unfortunate reality frequently overdetermined by words and rational concepts. This can be hard to bear without the detachment (or heightened involvement) granted by the more exterior or exultant aspects of life, whose sudden freedoms often act as a dismissive or optimistic counterbalance. For many thinkers and philosophers especially – perhaps already condemned by cast of temperament – the plod of living, must often feel inescapable, and a jaundiced or melancholy view is the likely result. The sense of dead end that occurs to everyone at times, cannot help but be exaggerated when life is viewed through the restricted binoculars of human society . . . as if that is what life and reality are solely about.

All things kitsch & Christmassy – Premature shed of glory, Hayes Garden Centre, Ambleside, Nov 22nd 2025

With binoculars fixed very closely, Christmas is perhaps the societal festival which most obviously attempts to either deny or glory in darkness. The sense of home – interior home, away from the frost and snow being increasingly confused or cancelled by climate change – and the ideal of families gathering (regardless of the recipe for trauma such get-togethers commonly revive), is clearly heightened in winter, as the year, in our human scheme, draws to a close and turns. Christmas, whatever origins the season is disputed to have[xiii], and however many traditions and modern exploitations it involves, is patently the most universally home-focussed time of year – the time to recall the past and, with the New Year, to make resolutions: casting hopes into a cancelled future.

That there is a kind of gloom inside my mind arising from such thoughts, goes hand in hand with a satisfying sense of a disconnected personal future, sealed, content, withdrawn:

An old figure inside a crumbling bay window, is putting decorations on a Christmas tree . . . a brief atmosphere seen in passing . . . to combine the homely and the lonely, as this character prepares to rewatch perhaps, and for the umpteenth time, the Avengers episode, Too Many Christmas Trees[xiv]. Since another condition of home is the repetition of the familiar and the reassuring – the repetition of tradition, combined in this case, with a biting nostalgia for black and white times lost – is this safe or claustrophobic?

The crumbling bay window, stone perhaps, and projecting from a small building under trees, evergreen or not, resembles my archetypal fantasy of the Lodge[xv], despite that on this occasion the character inside, dwelt in a bungalow amongst mixed houses and estates branching from Crag Bank Lane in a small Lancashire town. To me, perhaps the true lodge should be rural and remote? Yet Geiger’s phantasmagoric, lodge-like bungalow in The Big Sleep (1946) – with a Lynchian atmosphere in the year David Lynch was born – is surrounded by other small buildings in a movie studio with painted nights[xvi]. . .

Often, when my children were young and I was tormented by the commercially relentless approach of the Festive Season, I would threaten to “cancel Christmas!” Although this has since become a family joke, at the time, in our rural, middle-of-nowhere location, such an idea must have induced a sense of hollowness and dead end, requiring log fires, music, bright frost, snow or ginger wine to recover from. Pink Christmas trees would not have done it. Rather, the recent scene I descended upon permeating the basement of M & S in Preston (as early in the year as the 27th of October!!) had the singeing atmosphere of a prettified inferno:

Stairs & escalator descending into Hell, M & S, Preston, October 2025

Whenever possible, at least inside, I try not to see life in terms of human society. In a sense, the very concept of a future (as also the concept of progress) has always been something of a misapprehension. Progress is not that obvious ever-rising stairway that hopeful societies have been foolish enough to believe in. In fact, we have been mortgaging the ‘future’ for this pyrite (rhymes with . . .) for at least three centuries – and now are so vastly in debt we may have hit irreversible bankruptcy. As a race we have and are, ruining far more things than we will ever improve, but away from health benefits (on the verge of compromise or cancellation) short term acquisition and home comforts in our once, supposedly ‘rational’ climate, it is easy to miss this. Easy to miss from the mire of our relativist[xvii] loop.

Of course, to ‘ordinary’ people (whoever the hell they are), the cancellation of time, specifically the future; home versus dislocation; relativism good or bad; the psychology of Christmas, and so on . . . none of these concepts might matter. If they wish, they can continue to be simultaneously bored and fascinated by their various devices – a paradox Mark Fisher makes convincingly clear. Their technological devices are their future. Meanwhile, outside this mass hive head, (democracy in the worse sense of the word?) the entire future for humanity (as a literal extension of the construct of time) is being literally cancelled ever more recklessly.

So, are furniture vans or moving house, apt symbols for the restless, reckless state we are in? I could waste a lot of vanishing time forcing it to appear so. My son’s house moving was chaotic, the removal company at first appearing as dishevelled as Whiteleaf Removals . . . yet trying to shift home or base can be one of the most invigorating things we do. Or, in an age when only the landed gentry and a few traditional farmers have the luxury of a real sense of home, on from the housing estate island, floating over marshy fields on the edge of a town beyond the green belt, have I grown up a permanent exile? If so, this is clearly a common condition. The social and geographical mobility, forced to escalate so dramatically since the 1960s, however freeing it can seem personally, socially and politically, was also part of the general competition and jostling for position demanded by the capitalist Big Grab.

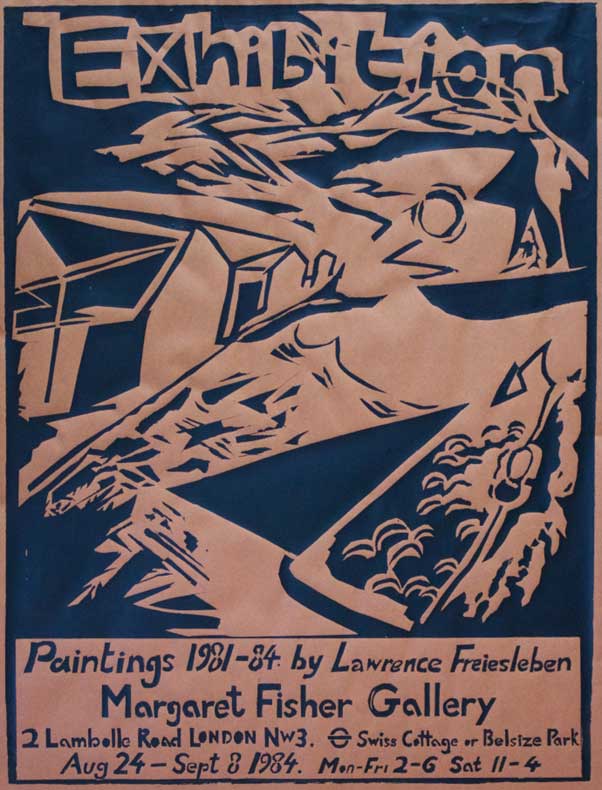

The housing terminus, ending in fields . . . Screenprint enlarged from a 1981 linocut

Although I’m fortunate to always been able to live protected by walls and under a roof, having moved twenty-three times, I wonder if I’ve demolished any real chance of finding a home in the pre 21st-century sense of the word? Perhaps the allure of differing landscapes and towns – each one unique – encountered in our constant shifting on, has barred such an antiquated ideal?

Was I permanently unsettled or given a gift as a child, by our first family move? The sudden freedom of a housing estate, extending into the fields. Was this an island of promise after the noisy chaos of London and our condemned house under the flyover? As far as I can recall, moving to that place – the newly built spacious rows of houses beside sandy roads, white crosses on the windows – was my first actual memory. But I don’t remember the process. Did my parents have too little stuff to need a furniture van? Could they fit everything they owned in my grandad’s car, or did he borrow a lorry from his work at London Airport? The closing shot (as I remember) of Going Home: Shebbear[xviii], an evocative film I’ve never been able to see since first catching it on TV in 1983 (?), is of some children looking out of the back of just the sort of huge box furniture van I remember crossing that bridge near Rushbeds Wood over the line now known as The Chiltern Line[xix]. The children watch as their past recedes.

Life is but a joke. Westgate, Morecambe, 21st Nov 2025.

Some memories have precisely the same texture as things which I read or wrote long ago. This must happen to everyone. Even the perfect personal photo – beyond home and beyond memory – is an idealisation rather than strictly the “truth”. Has the obvious fact that there is no real, lasting home in the physical world, inclined me towards the metaphysical?

We have never used a huge box van – in fact most of our moves needed nothing larger than a Transit-sized vehicle and lots of trips[xx]. The novelty of such dislocation may be enlivening, but since it is common for us all to experience and remember the same events quite differently, what exactly is memory? In what way is it different to fiction and how does it particularly relate to the deep-set idea of home? – a place or desire which is often set or lost in memories or fictions of the future or of the past.

© Lawrence Freiesleben

Begun August 2019, delayed until Oct-Nov 2025

NOTES – checked November 2025

[i] Now a nature reserve: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rushbeds_Wood

[ii] en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metro-land “The term Metro-land was coined by the Met’s marketing department in 1915 when the Guide to the Extension Line became the Metro-land guide, priced at 1d. This promoted the land served by the Met for the walker, the visitor and later the house-hunter. Published annually until 1932, the last full year of independence for the Met, the guide extolled the benefits of “The good air of the Chilterns,” using language such as “Each lover of Metroland may well have his own favourite wood beech and coppice – all tremulous green loveliness in Spring and russet and gold in October.” The dream promoted was of a modern home in beautiful countryside with a fast railway service to central London.”

Remembering growing up in Aylesbury and our fairly frequent rail journeys through Metroland to Marylebone, or, on Sundays, Baker Street, I was interested to rewatch both John Betjemen’s excellent 1973 film Metro-land www.imdb.com/title/tt0861719/ and the 1997 film. The latter proved a less welcome return visit:

Metroland 1997 18 – you are surely joking!) 1h 45m | It is hard to believe that a film with such beautiful settings can be so insufferable. Neither the wistful autumnal suburbia (including Amersham station – a station I used to get to art college in autumn 1978) of perfect leafy streets and house interiors, nor the thoughtful acting, can dilute the fundamentally despicable tone and the way this calmly annexes rebellion. All dislocation is smothered by the deep pillows of home.

No matter that the locations are real, the atmosphere (of Paris, of punk, of Metroland) is somehow depressingly fake. You never believe Chris could have taken any of the photos which purport to be his work, although he runs around and clicks away enthusiastically enough. His best friend Toni, is also counterfeit.

Perhaps the film thinks it was being daring (how did it come to be rated 18!?), but beyond the tag line “Metroland is not a place, it’s a state of mind,” very little in the script is sharp or inspiring. It may be accurate at times and even poignant, but anything good is swept away in its tsunami of complacency, its sense of limitation and defeat.

In the end, despite the obvious craftsmanship, the film feels as though it was poisoned by whatever compromises the makers felt to be present in their own lives. Perhaps they hoped they could overcome them by confessing their sins? Yet simultaneously, growing nervous about going too far, a puerile team of naughty schoolboys took over – Toni and Chris, smoking from the sidelines and dreaming of a cliched Paris. That was their rebellion.

Perhaps all the flaws come from the original novel by Julian Barnes and the filmmakers are not to blame? I did once read the novel and remember being unimpressed, but that was a long time ago and I could be being unfair.

[iii] This would have been the bridge near Wood Siding where the Brill tramway crossed the Great Western line to Bicester and Birmingham below, wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brill_tramway_system_diagram.png

Aged 7 or 8, Aylesbury to Brill was one of the first long cycles I did alone. Stupidly I neglected to take any food or drink. Getting back proved difficult.

[iv] The A41 here, often follows the Roman route of Akeman Street

[v] The old pub has been brought into the open (in fact, it seems to have moved to the other side of the road! which must be my memory at fault) and renamed The Akeman Inn (from the Roman Akeman Street which linked the Fosse Way and Watling Street) www.acornpubs.co.uk/akemaninn/

[vi] Based in Princes Risborough, I believe the company ceased to exist towards the end of the last century.

[vii] Certainty Under the Rose, (2013) version A, chapter 3, page 17, 2023

[viii] Certainty Under the Rose, (2013) version G, chapter 3, page 17, 2018

[ix] Paul Tillich, The Shaking of the Foundations, 1949

[x] It’s tempting to add that having worked for Whiteleaf Removals, I wonder how many customers had to be content to dwelling with the pieces of their previous home? Similarly, as Christmas paraphernalia is retrieved from loft or cupboards, it can be an evocative lottery to discover what has survived. But perhaps, nowadays, many people bin and buy again every year? What wonderful freedom we possess.

[xi] internationaltimes.it/the-pine-lake-manoeuvre/ and

memory-alpha.fandom.com/wiki/Corbomite

[xii] internationaltimes.it/the-slow-cancellation-of-time/ – a mention of which I first came across in 2017 via his obituary in Sight and Sound: bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/news/mark-fisher-obituary-thrillingly-creative-critic by Sam Davies

[xiii] See: historyforatheists.com/2024/12/pagan-christmas-again/

[xiv] internationaltimes.it/too-many-christmas-trees/

popculturereferences.com/classic-1960s-christmas-7-the-avengers-too-many-christmas-trees/

[xv] Numerous:

That dream could be the dream of the lodge, off the map, disused, forgotten / but self-sufficient – as in the end we must all become, unless (or even if) we can / rekindle love. Our own fracture is enough, only the landscape or the lover can heal, / not the peer group or the distant friend. / Once it becomes impossible to tolerate life as it is, there is only the light inside. Blackheath, lines 150-154, Aug-Sept, 2025

Is there some interior life that lives beyond the blue hills / in some red sandstone lodge, / ideal calm, reaching, where we could all breathe yes? Preston Court House, lines 7-9, Jan-Feb 2025

At least that escape to a mythical lodge, / – alone, self-possessed – / in forests or mountains concealed, / has by contrast, a proud, stark dignity. Imagination can be the truth for which the parade of reality is merely a sketch, lines 12-15, Nov-Dec 2022

The old lodge named Seven Dials was some eighty yards back from the junction where lanes meshed. Seven Dials, a short story of 2019.

And so on . . .

[xvi] To humorously contradict the darker aspects of the film, the film’s rushed romantic conclusion, ends with a shot of two cigarettes left smoking in an ash tray, representing the absence of Bogart and Bacall! Perhaps this contradiction could also be seen as Lynchian?

[xvii] plato.stanford.edu/entries/relativism/

[xviii] www.imdb.com/title/tt7530858/ By the time I watched the film, North Devon, (being my first long-distance move away from Bucks), where I lived in a caravan from summer 1980 to summer 1981, had come to feel itself like a long-lost time decades earlier in an earlier life, rather than only a couple of years earlier.

[xix] In 1930s photos with clear embankments and crystal-clear woods, this was a double track main line. By the time I was a kid, the track had been singled and the woods almost grew down to the track. Now the route has been doubled again and a new station, Haddenham & Thame Parkway, (no longer new) was added in 1987 en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chiltern_Main_Line

[xx] Although from Devon to Northumberland, I did borrow a seven-and-a-half-ton lorry.

.