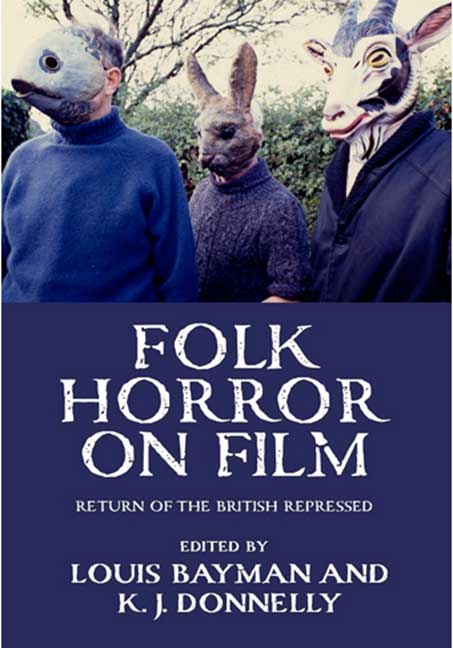

Folk Horror on film. Return of the British repressed,

eds. Louis Bayman and K.J. Donnelly (Manchester University Press)

Academic presses are strange beasts. Some are slow and lumbering, taking years to actually produce the books their writers have written or editors have assembled, others – despite print-on-demand technology – still only produce overpriced hardbacks that even university libraries can’t afford. Some even have to be persuaded to send out contributors’ copies, others don’t take on board that although academic writing may involve specialist vocabularies for their subject matter, in general good academic writing is clear and straightforward.

Manchester University Press are not one of these presses. When a book with a popular subject is added to their list they go for in the general marketplace, with paperbacks and ebooks on sale. Folk Horror on Film arrives on the back of ongoing and renewed interest in the gothic, wyrd and supernatural, psychogeography, the occult, place and hauntology, and is a marvellously diverse and engaging anthology. Manchester University Press are not one of these presses. When a book with a popular subject is added to their list they go for it in the general marketplace, with paperbacks and ebooks on sale. Folk Horror on Film arrives on the back of ongoing and renewed interest in the gothic, wyrd and supernatural, psychogeography, the occult, place and hauntology, and is a marvellously diverse and engaging anthology.

One of the most fascinating things about this book is the discussion of what constitutes and/or makes folk horror. Is it the ‘folk’, that is the people, and their cultural/religious/ritualistic activities? Is it land or landscape[s] which somehow shape what is going on? Or it somehow the result of recent history – half-remembered, distorted or causing mental distress and psychic unrest? Or perhaps it is an ongoing engagement with outsider, perhaps pagan or alternative, rituals, beliefs or traditions?

This discussion is first evidenced by three chapters about The Wicker Man, where straitlaced and abstemious Christianity, in the form of a police detective, is pitted against an alternative agrarian cult whose members live on an isolated island, and whose crops are failing. Sex, ritual, murder, music and festival all contribute towards the inevitable sacrificial ending… The film is quite rightly regarded as pivotal in shaping folk horror, although there are perhaps far too many mentions of this throughout the book! (As indeed there are of a few other films such as Witchfinder General and A Field in England, which is not to undermine their importance.)

Mikel J. Koven, who writes the third chapter in the section specifically about The Wicker Man, widens the discussion to include Neil Jordan’s The Company of Wolves, the eerie adaptation of Angela Carter’s own reversioning of dark fairy tales, and the second section of the book continues this opening out of subject matter and debate. Particularly interesting is the inclusion of some unexpected dramas and documentary, namely Doomwatch and Requiem for a Village, where discussions about ‘sacrifice zones’ and ‘socio-cultural change’ are undertaken.

The same section also contains Amy Harris’ overview and discussion of ‘Women’s folk horror in Britain’, and considerations of ‘outsider history’ and ‘the folk of folk horror’, as well as an intriguing but way too short chapter on ‘Anglo creep and Celtic resistance in Apostle‘ by Beth Carroll, although some of my response to this is no doubt due to the fact I have never seen (or to be honest heard of) Apostle before.

The third and final section is, as often happens in academic books which are the result of open calls for submissions, a bit of a hodgepodge. There is a chapter on the sensory effect of drums in folk horror, a rather personal take on ‘Arthur Machen on screen’ that, for me, required more critical distance, as well as more oblique takes on folk horror films using ‘social, political and cultural influences’ to frame ‘urban wyrd and backwoods cinema’ in relation to the concept of Albion, and an intriguing but undeveloped discussion of ‘the folk horror anti-landscape’ which suggests that ‘Nature came before man’, rather than man simply being part of nature himself.

The final essay is Diane A. Rogers’ response to the provocative question ‘Isn’t folk horror all horror?’ It’s a good place to end the book, and although I’d like to have seen more about the use of music and sound design in folk horror, along with more unusual and surprising films discussed, overall this is a highly readable and enjoyable collection of criticism and debate which has had me revisiting various films and books in my collection.

.

Rupert Loydell

.