Extract from ‘Up in Smoke: The Failed Dreams of Battersea Power Station’, by Peter Watts

www.paradiseroad.co.uk

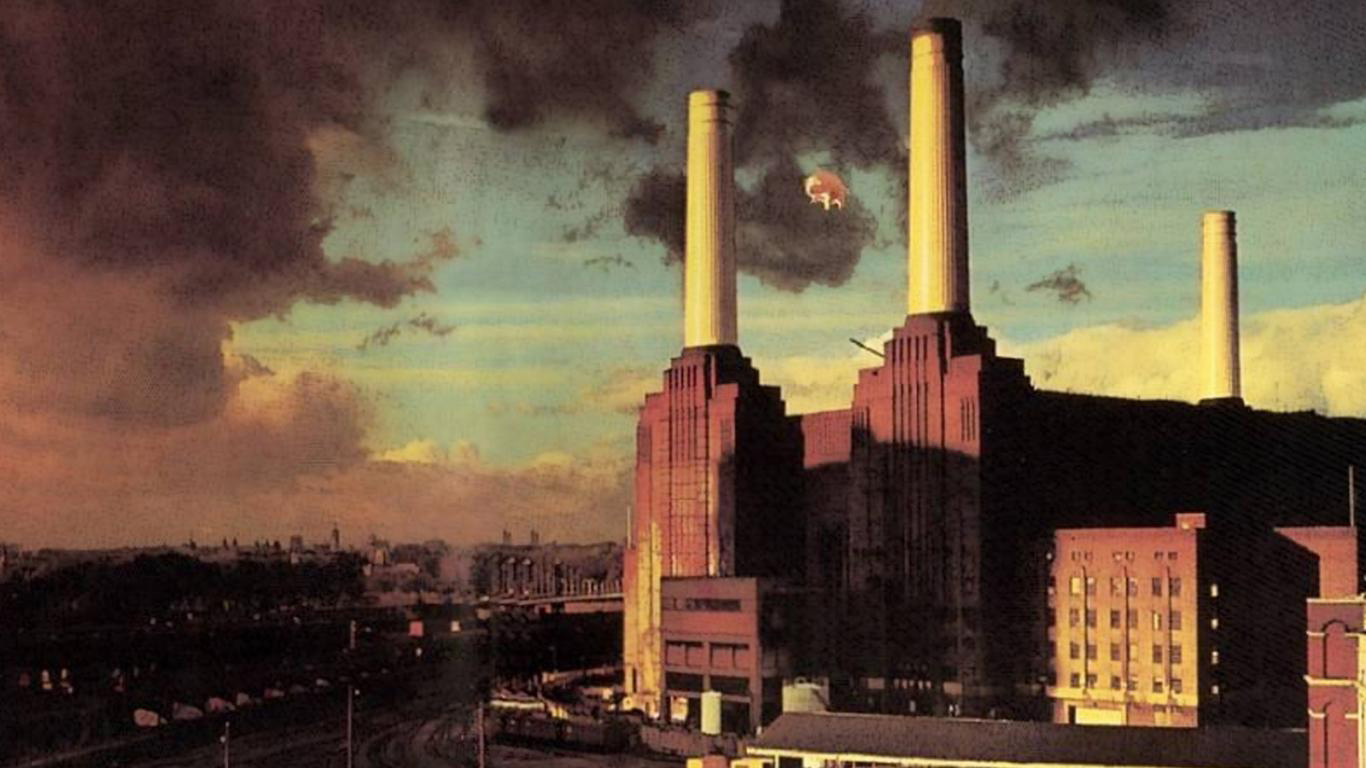

Battersea Power Station was already a national landmark when Pink Floyd put it on the cover of their 1977 album Animals. But the resulting piece of art, showing a moodily lit power station against dramatic London skies, with a small incongruous pig hovering between the two southern chimneys, took the building’s fame to another level. It may even have helped pave the way for the power station’s later elevation to listed-building status as it transformed Battersea from a purely London landmark to a piece of rock iconography familiar to millions all over the world.

It was Roger Waters, the driving force behind Pink Floyd in the 1970s, who came up with the cover concept for Animals. The execution was by Hipgnosis, who did all of Pink Floyd’s artwork between 1968 and 1979. They were a design agency formed by Aubrey Powell and Storm Thorgerson, a combustible pair who had grown up in Cambridge with Waters and Syd Barrett, two of Floyd’s founder members. Hipgnosis was highly regarded among musicians for its imaginative concepts and attention to detail, even if record labels sometimes balked at the costs or were baffled by covers like Atom Heart Mother, done for Floyd, which was just a photograph of a cow in a field, no band name, no album title. But bands trusted Thorgerson for his ability to create truly memorable imagery, such as the mysterious prism for Dark Side of the Moon, which would become something of an emblem for Pink Floyd.

At Waters’ request, Hipgnosis had already knocked up one idea for Animals, which featured a small child clutching a teddy bear at an open bedroom door, watching his parents furiously copulating. Waters wasn’t convinced and went away to have a think. “Roger was living in Battersea and he invited me round for tea,” says Aubrey Powell when we meet in his flat, coincidentally just across the river from the power station. “I went to the flat and he said, ‘Look out the window, what can you see?’ and I said, ‘Battersea Power Station’. He said, ‘Isn’t it absolutely fucking amazing? I’d like to use it on the next album cover.’”

Waters told Powell that he wanted to fly an inflatable pig above the power station. “I thought it was interesting but I wasn’t quite sure where he was coming from. He said he wasn’t sure either but we should go and have a look.” The pair drove to the power station and explored, Powell taking photographs to get an idea of the landscape. After consideration, they decided they wanted the pig between two chimneys and Powell set about getting permission.

This was surprisingly easily achieved. The power station management had long accepted that their building had a burgeoning secondary career in modelling and film, and now it was becoming a fashionable accessory in the music business. In 1965 it had appeared with The Beatles in Help! then eight years later The Who included a photograph of it in a booklet to accompany their Mod rock opera Quadrophenia. Freak rockers Junior’s Eyes, who backed David Bowie on Space Oddity, called their only album Battersea Power Station. In 1971, Slade recorded a promo for single “Get Down and Get With It” on Battersea’s roof. If the power station could survive Noddy Holder’s mutton chops and throaty yodel, what threat did a pig-shaped balloon present?

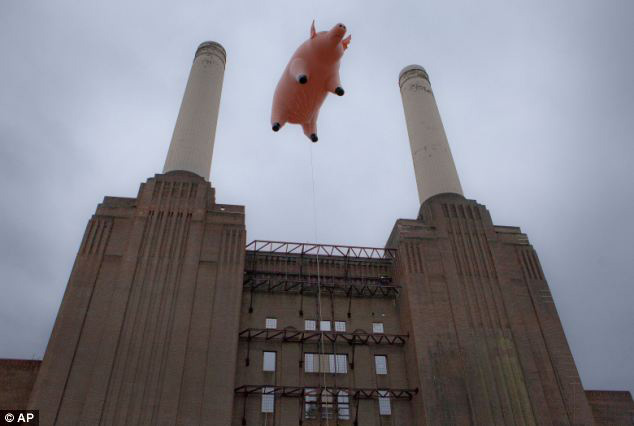

An inflatable pig floats today over the Battersea Power Station on the Thames River in

An inflatable pig floats today over the Battersea Power Station on the Thames River in

southwest London to herald the release of new remasters of the band’s 14 studio albums. 2011

Pink Floyd had experimented with inflatables at gigs before, notably a giant octopus floated on a lake in Crystal Palace Park in 1971. That had been made by Australian artist Jeffrey Shaw and his colleague from the Netherlands, Theo Botschuijver. To make the pig, Waters turned again to Botschuijver. The plan was for the pig to be photographed on the album cover and then taken on the subsequent tour, so Botschuijver had to create something that would stand up to scrutiny. After visiting local farms, he began making models. “The danger I noticed straightaway was that it could look like a Walt Disney figure,” he says over the line from the Netherlands. “Pigs are usually portrayed as friendly, chubby, cartoonesque animals but [Roger] wanted a realistic pig, more aggressive.” The final pig did look pretty fearsome, with black rings around narrowed eyes, a sneery wrinkled snout and two fearsome tusks poking from a downturned mouth.

It was manufactured in Germany by a company called Ballonfabrik with a little reluctance: “They didn’t like my pig,” Botschuijver says. “I had a lot of trouble convincing them this was the pig the band wanted.” After some persuasion, the company delivered what was required, a mean-looking porker about fifty-five foot long and made out of a thin, rubberised cotton.

The shoot was scheduled for Thursday 2nd December 1976. Hipgnosis was after the full package: photographs for the album’s covers, front and back, and inner sleeve, which could also be used on badges and posters, plus footage for a promotional film. Aubrey Powell had engaged around a dozen photographers, chosen for their range of styles. The principal pair were Howard Bartrop and Dennis Waugh, who were given plum positions in front of the power station on the southern side – Waugh on the railway sidings and Bartrop, who had taken several cover photographs for Hipgnosis, slightly elevated on the balcony of some flats. “Howard had the prime position, he had the whole landscape while other people were doing reportage, wandering around shooting on the ground,” says Rob Brimson, a Hipgnosis photographer. Another photographer, Robert Ellis, was positioned on the roof, while Brimson was supposed to be aboard a helicopter, which was waiting at the nearby Battersea Heliport on standby. Waugh appreciated the chance to get close to the power station. “Growing up in New Zealand, I was brought up on images of London and one thing I remember is the disappointment at how small everything really was,” he says. “Battersea was different.”

On the railway bridge, Powell had painted the word “Animals”: the intention was to get a photograph with this in the foreground so the album title would be incorporated into the urban landscape. Powell ended up cropping it out of the final image but for years afterwards the fading graffiti could still be made out.

On the bitterly cold morning of the shoot the photographers, band, the pig – now christened Algie – and its handlers assembled at the power station. Champagne – pink of course – was served to toast the big event. There was a sense of expectation in the air. But Algie would not perform. Botschuijver explains: “Gas when it expands gets quite cold and freezes in the bottle and none comes out. So we couldn’t inflate it, it didn’t work. We parked it by the power station half-inflated and decided to come back next morning.”

The next day they made a second attempt. Robert Ellis, an experienced rock photographer, took his position on the power station’s roof. “I’ve no idea why I was there, other than perhaps they took pity on me and gave me a cosy spot on a freezing cold morning,” he says. “Up there it was just warm steam blowing about in the cold wind like from a smoke machine on some giant rock stage. The main thing was dirt, coal dust, and getting up there was a long and difficult climb. I had to go round the back by the Thames, clambering over piles of coal to get to iron rings set in the walls and then up into the loading bays, across the vast area over more heaps of coal to get to a stone staircase up through several floors until a last set of iron steps leading to a hatch in the roof and out into the open air.”

With everybody in place, the pig was inflated and was soon airborne, rubbing against one of the chimneys. “The thing was anchored to a winch on a truck,” says Botschuijver, who was monitoring progress. “Somebody walked past with a camera and wanted a picture so he asked for it to go higher and the guy from Germany loosened the winch and it started to unwind. He jerked the brake and I heard – ding! The ring broke and the pig flew away.”

Down on the railway tracks, Dennis Waugh was watching the pig’s ascent. “I remember thinking, that’s rather high and then… fuck me, they’ve lost it!” Brimson was waiting for the pig to take to the air before heading off to board the helicopter: “It was amazing how fast it went,” he says. “Everybody watched it go and there was absolute panic.” Howard Bartrop was just worried that he’d missed his shot: “I remember seeing it go and thinking I was in such trouble because it was now out of frame and definitely not between the two chimneys,” he says. “That was the brief, to get it between the chimneys. But the pig didn’t want to play.”

First to react were the band themselves. “Pink Floyd ran away,” says Powell. “They laughed, jumped in their cars and drove off while we all stood around wondering what to do.” Powell was worried the pig would fly into the Heathrow flight path and contacted the police. Botschuijver snatched some photographs for posterity and then diligently covered his own backside. “This was the first time I had lost an inflatable,” he says. “I scouted the terrain to find the metal ring that broke, which I found and put in an envelope. Then I went to the telephone and called the nearest lawyer and made a statement that it was my design but the execution was German.”

Brimson was sent to the helipad. “The pilot was ready to go and we were going to pile in, work out where the wind was blowing and chase the fucker, but it was already gone. We’d lost the pig.”

Powell admits being terrified. “Storm and I hustled off to our studio in Denmark Street where we immediately put it out on radio that anybody who saw this pig should get in touch,” he says. “Airline pilots were reporting seeing it at 30,000 feet and it was a real danger. They had to shut down Heathrow. If it happened today I’d be in prison. The RAF sent up fighter jets to try and shoot it down. I was freaking out, I thought I’d be responsible for an airliner crash.”

The pig’s escape was gleefully reported by the press, with some of the more cynical wondering whether the whole thing was perhaps an elaborate publicity stunt, something Botschuijver and Powell are at pains to deny. Later that evening, Powell was waiting with a policeman for news when he took a phone call. “This man asked if we were the people looking for a pink pig, because the bloody thing was in his field frightening his cows.”

The gas had contracted in the evening air and the pig had crash-landed in a field in Kent, where it bounced around in the mud, semi-inflated. A road crew was despatched to haul it back to London. “It was slightly damaged but we got it back and did cleaning and repairs,” says Botschuijver. Would it be third time lucky?

The shoot had already taken up far more time and money than Hipgnosis had planned, so the number of photographers was halved for the third day of shooting. This time the pig took flight without any mishap and the photographers had their moment. The helicopter was also let loose, with cameraman Nigel Lesmoir-Gordon capturing some wonderful film of the pig floating above the station. Brimson was aboard taking stills and worried he was “going to chuck up over London” as the helicopter spiralled round the smoking chimneys.

Which brings us to the cover shot itself. Three principal witnesses each remember this being taken on a different day. For Powell, it was the very first day – the day of the non-inflating pig – when “it was the most spectacular and romantic day lighting wise, it was Turneresque, amazing clouds, a really extraordinary early winter day”. Brimson believes the shot came on the second day, shortly after the pig had escaped. And Howard Bartrop, who took the photograph, remembers it happening on the final day.

What everybody agrees on is that while the power station looked splendid in Bartrop’s photo, it didn’t feature a pig. “The best shot was from the first day, with this unbelievably dramatic sky,” insists Powell. “It looked incredible but the pig wasn’t there. On the third day, there was the perfect image of the pig between the stacks, so we stripped the pig from the third day and put it in the picture from the first day.”

Having shot six or seven photographs over the course of the three days, Bartrop’s recollection is that he was packing up to go home on the final day when the sun suddenly reappeared. “Occasionally there’s a gap on the horizon between the cloud base and the horizon itself not much bigger than the disc of the sun, and that’s the exact space the sun was in,” he says. “I ran like hell back up the stairs and got into position. I knew it looked fantastic but I had no idea whether they wanted something so classical. I had a feeling that somebody underneath with an ultra-wide angle getting the two chimneys with the pig coming up from the bottom would be the strongest image. But in the end it became more of a portrait of the building than of the pig.”

The question remains: why Battersea and why a pig? At the time, Waters was evasive, telling a London radio station only, “I like the four phallic towers and the idea of power I find appealing in a strange sort of way.” But in 2008, he opened up more fully to Rolling Stone explaining that he chose the power station because, he said, he’d always loved it as a piece of architecture. He also ascribed a certain symbolism to it: “There were four bits to it, representing the four members of the band. But it was upside down, so it was like a tortoise on its back, not going anywhere, really.” It is a recollection perhaps tempered by hindsight: Waters left the band in the 1980s and then spent much of his solo career in a monumental huff that his old friends could carry on without him.

And the pig? Aubrey Powell offers this: “You need to put this in the context of the time. Pigs were policeman in the Sixties and Seventies. The pig was a symbol, a way for Roger to bash people he didn’t like. The pig was a way to put down ‘The Man’. It was like the power station was this immense factory, filled with drones, worker bees, with the pig over it, this figure of hate. It’s an extraordinarily powerful and potent image.”

“People see it as a fun image,” says Rob Brimson, “but I always saw it as profoundly disturbing and making a very strong comment on the relationship between power, in this case electrical power, and the fat pig.”

The pig went on tour with the band and the metaphor became even more macabre. Theo Botschuijver was asked to add searchlights for eyes and a panel in its belly so its guts could spill out. (A request to wreathe the pig with the smell of cooking bacon could not be fulfilled.) When Waters left Floyd he took Algie with him and used it in his solo shows. His former band mates, who continued to record and perform as Pink Floyd, had their own pig made, adding conspicuous testicles to differentiate it from Waters’ sow.

Despite all the complications, Hipgnosis was not done with the power station. Brimson recalls shooting two further covers inside the building: one of the turbine hall for rock band UFO (Lights Out, 1977) and another for Hawkwind (Quark, Strangeness and Calm, 1977) in the control room. And, of course, post-Animals other musicians would continue to channel its dramatic form: The Jam filmed the video for “News of the World” on the roof, and it featured in videos by artists as diverse as Bill Wyman and Hanson. It appeared on the back cover of Morrissey’s 1990 album Bona Drag and inside Muse’s The Resistance in 2009. It inspired a song, “Battersea Odyssey”, by Super Furry Animals in 2007.

Even Pink Floyd renewed its acquaintance, returning in 2011 to celebrate the 35th anniversary of Animals, when an inflatable pig was once again hoisted up between the chimneys. This time it was not Algie, who by now was no longer airworthy and had been retired to a barn in Suffolk.

“When I look back at all the aggravation, we could have just taken the photo of the pig in the studio,” says Powell. “But we believed everything should be done for real. That was always what we did and the experience was part of the whole process. We wanted a living sculpture, a one-off moment. It became a very important symbol for Pink Floyd, and the association of Battersea Power Station became cemented with the band. But it wasn’t a publicity stunt, it was a pain in the arse.”

Peter Watts

from ‘Up in Smoke: The Failed Dreams of Battersea Power Station’, published by Paradise Road. Available from selected booksellers, online retailers and from the publisher at www.paradiseroad.co.uk