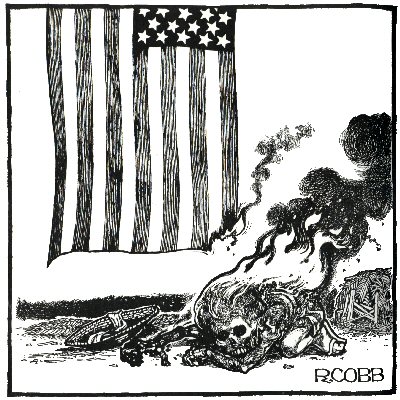

Ron Cobb was the greatest political cartoonist of the twentieth century.

For a decade between 1966-76, his political cartoons were the most brilliant graphic voice of america’s new anti-establishment generation. From the Vietnam war to inner city race riots, from gun culture to the felling of ancient forests, Cobb covered it all. Then, suddenly, one sunny California day, the cartoons stopped.

Cobb was born in 1937. As a teenager, his main interests seem to have been science fiction and later science and art, especially in combination. He read Asimov and was an enthusiastic admirer of the artist Chesley Bonestell (1888-1986) who “inspired an entire generation of astronomers, artists, writers, engineers and visionaries with his remarkable paintings. He illustrated the seminal Conquest of Space with author and space travel evangelist Willy Ley, with new paintings of unimaginable sights throughout the solar system.” (1)

By the age of 17, Cobb was working for Disney Studios in Burbank, California as an animation breakdown artist, progressing to become an ‘inbetweener’ on the animation feature Sleeping Beauty (1959), the last Disney film to be produced with hand-inked cels. (2)

Cobb was laid off from Disney once the film was finished in 1957 and he spent the next three years in a variety of jobs – mail carrier, factory worker, assembler in a door factory, sign painter’s assistant – until he was conscripted into the US Army in 1960. He drove classified documents around San Francisco for two years, before spending 1963 in Vietnam as a draughtsman for the Signal Corps.

When he got his discharge papers, Cobb freelanced as an artist and began contributing to the fledgling Los Angeles Free Press or ‘Freep’. Cobb says, “I always had to find paying work elsewhere while contributing to the Freep. In all my years of cartooning I never made a living from the underground press.”

The Freep was “among the most widely distributed underground newspapers of the 1960s and is often cited as the first such paper. Edited and published (weekly for most of its existence) by Art Kunkin, the paper initially appeared as a broadsheet titled ‘Faire Free Press’ in 1964, then became the LA Free Press newspaper in 1965. Notable for its radical politics when such views rarely saw print, the paper also pioneered the emerging field of underground comix by publishing the ‘underground’ political cartoons of Ron Cobb.” (3)

The Freep was part of the Underground Press Syndicate, a group of about 60 US magazines and papers freely sharing their contents – contents which included Cobb’s cartoons. “Anyone who agreed to those terms was allowed to join the syndicate. As a result, countercultural news stories, criticism and cartoons were widely disseminated, and a wealth of content was available to even the most modest start-up paper. Shortly after the formation of the UPS, the number of ‘underground’ papers throughout North America expanded dramatically.” (4)

By 1970, Cobb’s publisher could boast that his cartoons were appearing “in over 90 college newspapers and a number of establishment dailies.” (5)Cobb contributed cartoons to the Freep for six years until, in 1972, he set off on a tour to Australia and New Zealand. The tour – 14 speaking / slideshow dates between June and July in the major cities – was organised by the Aquarius Foundation, the cultural branch of the Australian Union of Students. Cobb wasn’t an unknown down under as his cartoons had been published in Broadside and Farago since 1969 but he took with him longtime friend, Phil Ochs, the most outstanding protest singer of the 60s and 70s, so the Foundation would make its money back.

Reviewing an early Melbourne university event, where Cobb and Ochs appeared with Captain Matchbox, Laurel Olszewski wrote in the music magazine Go-Set:

“I went along to the first Melbourne Uni. Concert. A quite sincere guy, and apparently at a loss because of lack of planned illustrations on slides, Ron Cobb didn’t speak much, or well, about his cartooning. He did talk about some of the subject matter though – ecology, politics, with the help of the audience who asked questions.”

Cobb remembers his performances getting better as the tour progressed, noting a relation between improved speaking and improved functioning of projector equipment. And he liked Australia. Not least because the tour was run by Robin Love who would later become his wife. He stayed for a year, making a travel film with Love and had a number of cartoons – 12 – published by the Melbourne-based satirical magazine, the Digger.

After twelve months in Australia, Cobb returned to California where he picked up cartooning with the LA Free Press. He also produced drawings for the Dan O’Bannon – John Carpenter feature film, the sci-fi black comedy Dark Star (1974), designing the exterior of the spaceship and suggesting many ideas for its interior.

Cobb had published four collections of cartoons in miniscule print runs by 1970, but in 1975 he collected “all the famous cartoons from his past books, as well as those done recently for The Digger and the Los Angeles Free Press” and published them as The Cobb Book, a 112 plate compilation, through the small Australian outfit Wild & Woolley.

Three years later and with the same publisher, Cobb put out another collection, Cobb Again. Although the book was published in 1978 and claims “This new collection consists of new cartoons from the last three years”, the drawings are all dated from the period 1974-76. These were the last of the line. After 1976, Cobb produced no more political cartoons.

Over the course of the decade, Cobb did a lot of other graphic artwork which never found its way into the collections. He designed record sleeves, postcards and book covers and collaborated in the production of comix.

The political cartoons stopped as he became more involved in concept design for the film industry during the second half of the 70s and the collections have been out of print for nearly 30 years. With almost zero online presence, these great works have drifted into obscurity and are now more underground than they ever were.

The decade 1966-76 was a momentous time, especially for young americans. While there are, no doubt, many histories of the period, Cobb’s cartoon corpus, coming from the front lines of counterculture radicalism, is a unique record of the times.

The era produced other cartoonists but none who matched the political credentials and technical abilities of Cobb or who had his depth of coverage – roughly a cartoon a month for ten years.

Introducing an interview with Cobb at the beginning of Raw Sewage, Eric Matlan enthuses, “His skill is consummate. But it is what he draws that is important, not how he does it.” The two aren’t as neatly separable as Matlan would like them to be. Without the visual brilliance, it’s unlikely Cobb’s political message would ever have made it onto the editorial pages of campus papers and then into book form. And how brilliant the visuals are.

From the beginning, his drawings show an incredible amount of detail. Several of the ecology cartoons in Raw Sewage, for example, have people moving around in a sea of rubbish or in the rubble and rubbish littered landscape of a post-nuclear apocalypse. Empty beer cans, old gloves, tyres, dead birds, dead fish, bottles, shards and shattered bits of wood are piled up to illustrate the “efficiency, utility, expediency” of consumer culture or the devastation of an atomic aftermath. (6)

Detailed draughtsmanship was also used to represent positive ideas. Patches of grass in ‘BANG! BANG! YOU’RE DEAD…’ or in ‘SHROUD’, for example, are incidental celebrations in a Dürer-type way of the simple natural forms which the ecologist Cobb valued so much. (7)

Preparatory, labour-intensive draughtsmanship was followed up with some equally detailed pen work. Cobb used a fine nib for inking-in and one of his trademark features was great areas of hatching – road surfaces, smoke clouds and the like. Three of the best examples from Raw Sewage are ‘BLESSED ARE THE MEEK’, ‘NO LOITERING’ and ‘SEQUOIA SQUARE’ where whole page surfaces are covered with this kind of work.

Another trademark is a thick black line around individual items in the cartoons – people, cars, whatever – which gives weight and physicality to two-dimensional representations. These lines, much thicker than the fine-nibbed marks of hatching, were nevertheless done with the same pen. The effect is impressive – heavy black lines with scratchy, scruffy edges support the otherwise precise and physically accurate world that Cobb draws. It’s interesting to look at because it contrasts – on the one hand it’s slick and on the other it isn’t.

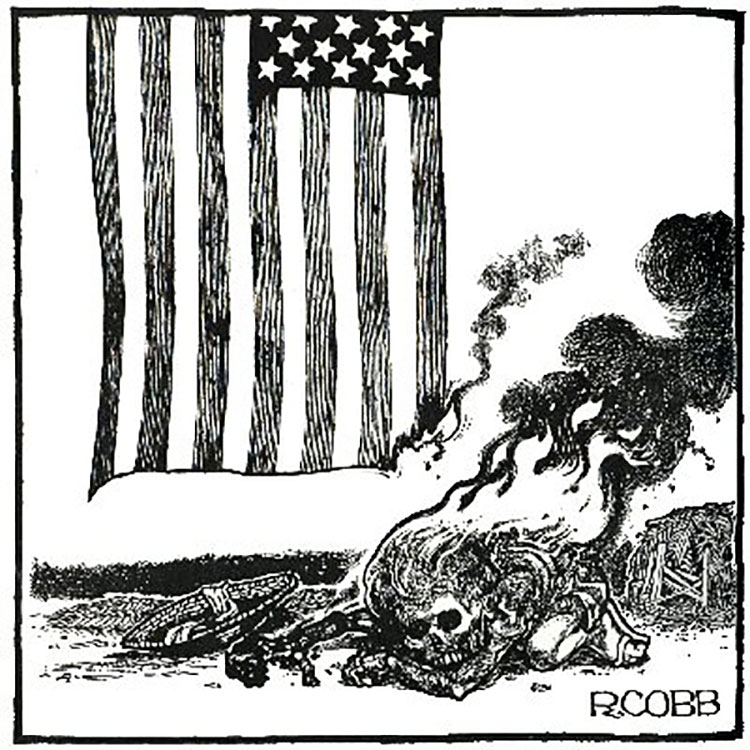

Many cartoonists have used strong areas of black and white contrast to good effect and Cobb is no different. Some of his best cartoons are virtuoso examples of this technique – ‘HO HO HO’, the aborigine cartoon, or ‘JUICY FRUIT’ about space litter, are both immediately visually arresting because of their dramatic and skilled use of contrast. (8)

Similarly, Cobb seemed to enjoy playing with perspective. An early cartoon from Raw Sewage, one with no text, shows an old man sitting on a bench surrounded by skyscrapers and concrete. At his feet a weed pokes through a crack in the pavement and he smiles to himself, tragically. Great cartoon. But the image is drawn looking straight down a path with high buildings on both sides which disappear into the distance and the perspective effect is, through it’s obviousness, a little bit contrived. The composition contrasts sharply with surrounding work and the image is one of Cobb’s most memorable cartoons. Similar demonstrations of foreshortening skill crop up again impressively in ‘SAUSAGE CITY’ (The Cobb Book) and in ‘NUCLEAR WASTE DUMP’, the cover of Cobb Again.

Cobb’s composition skills obviously got more adept as he got older. So did his characterisations. Uncle Sam, the assassin-war merchant in star spangled top hat was a speciality. But the expressions and postures of junta generals or old testament prophets are just as well conceived. The later cartoons from 74-76 which concentrate more on the relatively local political stories of US government, have many more caricatures of political personalities. Nixon, Ford and Kissinger now crop up regularly where they didn’t before and Cobb’s likenesses are faultless.

But ironically, as his skills got more polished and his subject matter more concentrated on specific events, the cartoons got more professionally routine.

Especially at the beginning of his cartoon career, Cobb’s drawings were general statements about the way of things, opinions condensed from the assimilation of a lot of cultural information, rather than reactions to particular events.

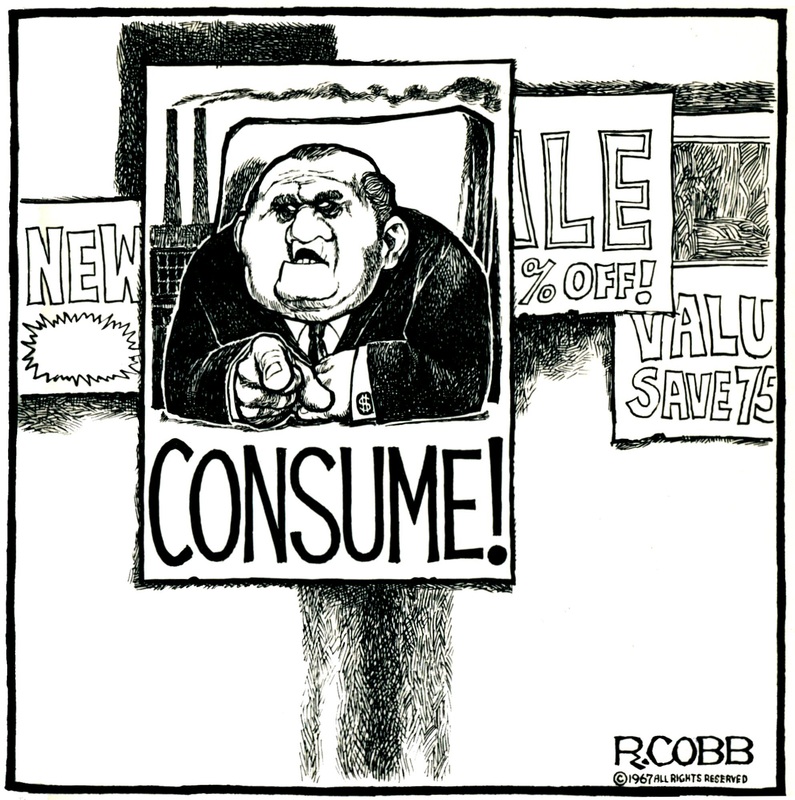

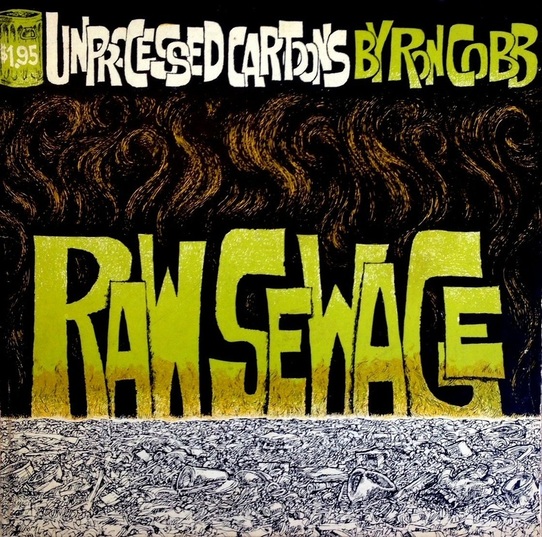

Raw Sewage is essentially an ecology manifesto where pollution, consumerism and the threat of nuclear war account for just about all the work.

There are no event-specific cartoons here. The book has some classic Cobb cartoons and features a great statement at the beginning – running to some 4 pages – in which, without pausing for breath, he delivers an account of man’s dependence on nature, his present contempt for it and the cartoonist’s hopes for a better ecological future. A typical couple of sentences read: “Ecology is really a dynamic realization, an awakening to processes older than reason. It’s a sort of ‘state of mind’, a recognition of the inter-relatedness of all things.”

This first collection also shows Cobb’s ongoing interest in space exploration and science fiction. More so than today, speculation about the possibilities of outer space in the 40s and 50s and subsequent developments in the US-Soviet space race, played a big part in peoples lives. Cobb was fascinated by this stuff and, even when he wasn’t drawing Mars landings, the science fiction element crept into other parts of his work. In this way, envisioning the future, sometimes in an uncannily accurate way, became a thematic trademark of his work.

Apart from the post-nuclear holocaust / disaster cartoons, there are other cartoons which deal with their subject in this futuristic way.

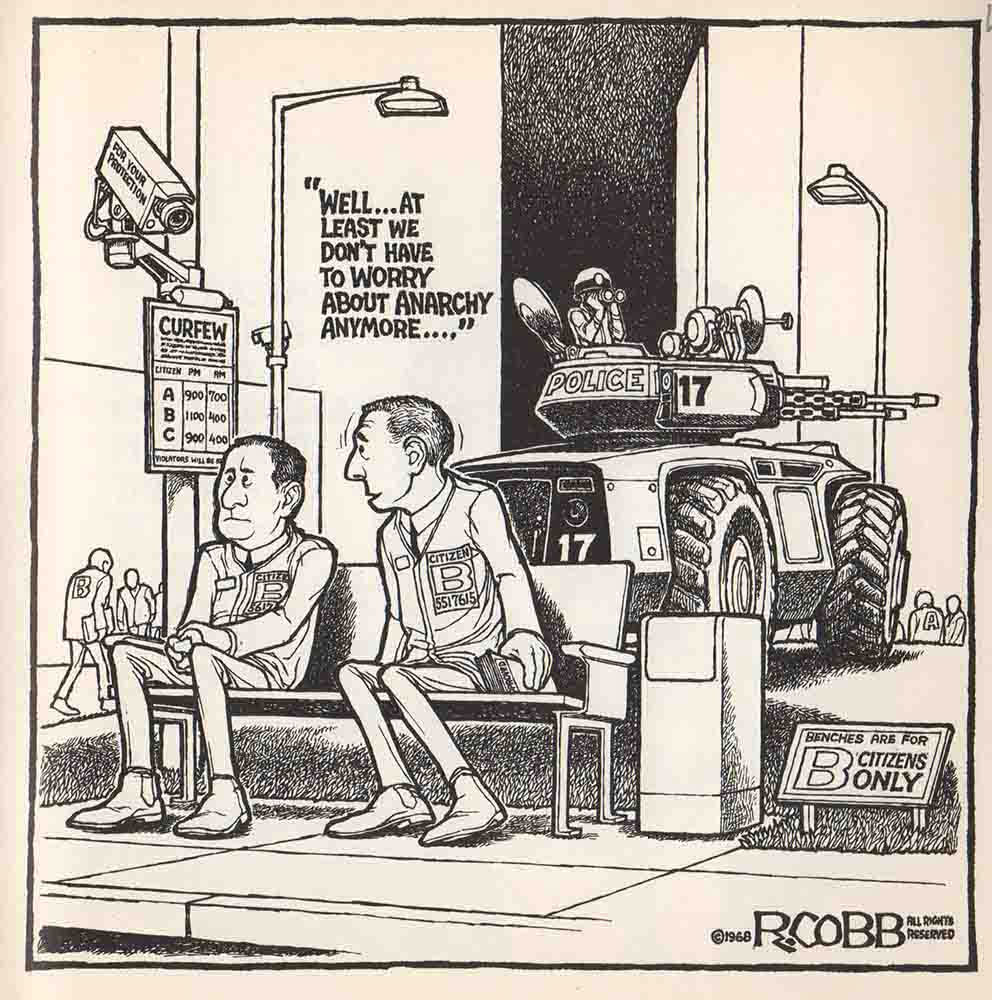

Commenting on an already oppressive law and order regime in the US, Cobb drew two uniformed ‘B-Class’ citizens sitting on a ‘B-citizens only’ bench on a street corner directly overlooked by a CCTV camera. The camera, which is attached to a pole with a curfew notice on it, sports a label saying ‘FOR YOUR PROTECTION’ while in the background an officer protrudes from an armoured police vehicle as he spies the street with binoculars.

The Cobb Book is subtitled, “Ecology, racism, drugs, disasters, law ‘n’ order, religion and outer space: eight years of cartoons from the underground press by Ron Cobb” and indeed, Cobb covers all these themes over and over again. Some of his best anti-racism cartoons were done in Australia in 1972 where the aboriginal peoples were, and still are, suffering appalling discrimination. One cartoon, which makes the back cover, shows a dead aboriginal man lying next to a dead kangaroo at the side of an outback highway as a sheep transporter drives by – both bodies are left as worthless roadkill.

There are a few drug cartoons in the later collections – a pot smoking self-portrait (top of this page) and a few other, more decorative stoned pieces – while RCD-25 is credited with containing “some classic drug cartoons”. Some ridiculing of religion rounds out the corpus.

It is amazing that this body of work has remained hidden from view for so long. Perhaps it finds itself in a parallel universe because anywhere else the original drawings would be doing world gallery tours, the cartoons would be reprinted in glossy hardback with wedges of peer interviews and background text and Cobb would be a celebrated man. Many of the cartoons haven’t dated at all and are as relevant today as they must have been then. Republish Cobb now is my advice: reproduction rights are held by Wild & Woolley.

Ron Cobb, a cartoon bibliography, 1967-78:

1967: RCD-25 (25 cartoons: Sawyer Press)

1968: Mah Fellow Americans (30 cartoons: Sawyer Press)

1970: Raw Sewage (38 cartoons: Price Stern Sloan and Sawyer Press)

1970: My Fellow Americans (40 cartoons: Price Stern Sloan and Sawyer Press)

1975: The Cobb Book (112 cartoons: Wild & Woolley)

1978: Cobb Again (84 cartoons: Wild & Woolley)

notes:

(1) the ‘Chesley Donavan Foundation’ takes its name from the artist Chesley Bonestall and Asimov’s “cheery engineer” Donavan who appeared in I, Robot (1950).

(2) “inbetweens are the drawings that fill-in between the keyframes. The inbetweener is the person who draws them. A keyframe is a main pose within a sequence of animation. A key animator will draw key poses and indicate the timing and number of inbetween drawings required. breakdown [is] the frame by frame analysis of sound tracks so that animation can be frame accurately synchronised to the sound” http://www.animationpost.co.uk/doping/glossary.htm

(3) http://www.answers.com/topic/free-press-1

(4) http://www.answers.com/topic/underground-press-syndicate

(5) blurb, Raw Sewage

(6) quote from ‘GROSS WORLD PRODUCT’ (Raw Sewage)

(7) ‘BANG! BANG! YOU’RE DEAD…’ (The Cobb Book), ‘SHROUD’ (Cobb Again)

(8) both cartoons from The Cobb Book

the first recent statement by Cobb about his 60s and 70s cartoonsToward the end of the sixties and well into the seventies I began to detect a flagging of cartoon ideas, along with a more alarming evaporation of originality. In the rush to meet my weekly deadlines I began to catch myself subtly using the same, thinly disguised visual paradoxes from earlier panels, to comment on something entirely different. Also, more political caricatures began to appear confirming my worry that I was exchanging illumination for finger pointing.I had truly become sloppy with the content of the cartoons while conversely, growing in my attraction to the film medium. It wasn’t an interest in animation that pulled me. My two years at Disney taught me that animation lacked spontaneity. It was the writing, and possible directing, of live action short films or maybe features that intrigued me now.As for the cartoons, I just had to stop, take a break and see if my focus would return. After all, it was always the thrill of seeing some irritating or terminal condition of life, society and/or history in a whole new light, an illumination that might even suggest a way out, that had always spurred me on. And now that satisfaction was fading. It certainly wasn’t the money. Yet, at the same time my interest in film-making felt much like the renewal of the same process I experienced when I first started cartooning.Everything seemed to say I should move on. So I did.I continue to write screenplays, teleplays and children’s books with some limited success. I have even returned to cartooning from time to time with panels appearing in the LA Times and other more obscure publications. i’ve had to change my mind about animation, it’s become highly automated, less collaborative and far more spontaneous. I am now rather keen to create small animated films with the help of my Mac.—————–My decline in imagination and motivation concerning the cartoons was long and gradual. That is, long before and long after we lost Phil Ochs. I have encountered a few written speculations that there was some connection between the termination of my weekly cartoon and the death of Phil Ochs or, possibly even the end of the sixties. Toward the end of his life Phil increasingly suffered from manic/depressive episodes. By that time all his friends and family had been trying desperately to help him for many years. Robin and I, along with Jerry Rubin and others were all in New York trying to help Phil through the last, deepest depression of all, just four days before he ended his life. Of course it had a devastating effect on all of us, and still does, but the example of Phil’s life was far more a call to redouble lose up shop. Anyhow, I feel strongly that Phil’s death was in no way the cause of my mid stream shift.Also, it should be said, I never identified that much with the counter-culture, the new left or “The Sixties”. I fully expected flower power to wilt and teach ins to teach out. Some of what happened was partially effective like the women’s movement, but most of it was too faddish, emotional and self indulgent (read, American) to really fit the complex mix of world events and thus, change things in all the intended directions.

(I know the political activism of the Vietnam years are widely thought to have accomplished a great deal, but I truly question this as I think history will as well.) It is clearly demonstrable that Vietnam changed everything with absolutely zero correlation to anyone’s expectation on any side of the conflict, (including the current Vietnamese government).

All my Vietnam cartoons were as much observation and comment about the movement as about the war.

I grew up in the forties and fifties amid the famous angst-riddled generation known as the Eisenhower years. This is when all the middle class kids of the cold war retreated into dark coffee houses to become “serious”. Soon they emerged throughout urban America as the “Beat” movement. I saw this as a signal, more than anything else, of the country’s tentative but long awaited willingness to listen and speak of dark things. Unfortunately, The Beatnik’s sober discussions were limited to “the Bomb”, jazz and Existentialism. But such gloomy restlessness seemed to trickle down and out into society where other less “hip” people were beginning to sense a feeble license to bitch and moan. First they bitched about racism, poverty and brutality then they demanded change. For while the war to rid people of totalitarianism was over, bad things were still happening to people all over the world and a lot of them were right here.

It was this post-war wave of protest and optimism, the fear of McCarthyism in high school, Civil Rights, the Cold War, that I enthusiastically co-opted and supported for 5 decades. The issues went on to become, Cuba, Religion, Knee-jerk Militarism. Christian attacks on education, Vietnam, etc. and I loved commenting on them all but, without any substantial reference to political theorizing or rhetoric. My viewpoint has always been art/science. I am deeply skeptical of the ultimate relevance of politics to actual human behavior in the real

world. On the other hand, the ongoing analysis of human biology, behavior, natural history and brain function tends to increasingly reveal political philosophy as subjective rationalization, wishful thinking and the stubborn preservation of infantile over-generalization. Politics are all too real but I prefer doing a cartoon about politics than doing a political cartoon about anything else.

As a middle class, white, sappy secular humanist, I desperately wanted to learn how to convert my bitter disappointment and anger into a clarification of the debate and a contribution to the winning of real

social and cultural transformation, no more, no less. I still think this opportunity is as open now, as it ever was, only it’s just getting harder to be heard.

Published in http://silbergalerie.weebly.com

I still have an R. Cobb cartoon that appeared in the Syracuse University campus paper in around 1965 – 1969. The caption is “Man’s Conquest Over Nature,” and features a shrivelled man in a wheeled cart in a landscape of endless pavement devoid of any plants, trees, or features of the natural world. Always loved this outrageous depiction of a seemingly prevalent attitude toward technology and development. . It is this lingering interest in Ron Cobb’s cartoons that brought me to this web page. Thank you so much for chronicling his accomplishments and biography. I am hoping to find some of the publications noted in this summary. Clearly, many of is themes are a relevant today as they were in the ’60s and ’70s.

Comment by John Brucato on 13 March, 2019 at 10:08 am