Jay Jeff Jones

“If death can fly, just for the love of flying,

What might not life do, for the love of dying?”

Malcolm Lowry

At night, seen from on high, Las Vegas is a shining scar of imagination, an alchemic mess of colossal signs, absurd structures and cloud-slicing laser beams that combine with kaleidoscopes of endless showtimes, robotically spun mechanisms of chance and humdrum urban power consumption to burn through thousands of megawatts per day. ‘Armageddon in neon’ is what architectural writer Paul Davis called the main drag – an ‘…engagement with the luxury of waste on the one hand, and fakery on the other.’[i]

***

Two bags of grass, seventy-five pellets of mescaline, five sheets of high-powered blotter acid, a saltshaker half full of cocaine and a whole galaxy of multicoloured uppers, downers, screamers, laughers…a quart of tequila, a quart of rum, a case of Budweiser, a pint of raw ether and two dozen amyls.

Vodka, whiskey, gin.

These cargo lists for two literary road journeys – one semi-imaginary, the other a complete fiction – were compiled almost 20 years apart. In both books, the lifestyle essentials of central characters mirror those of their authors and the cars travel over the same route, from the City of the Angels to the City of the Meadows. On early maps the destination is simply marked ‘Vegas’, now the louche diminutive for 20th century America’s original adult playground city. It was the location of an artesian well on the Old Spanish Trail and therefore a reliable water source for gold prospectors heading West.

Vegas as the place you can always get a drink is given as the foremost purpose for the journey taken by ‘Ben’ in John O’Brien’s novel Leaving Las Vegas. For him, this will mean never again resorting to shots of Listerine during long mornings in LA before the first bar opens. More importantly, there will be no further interruptions to his plan of drinking himself to death.

Nor did it matter any less to Hunter S. Thompson in Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas, an account of everyday depravity in a city where the doors of merchants of the more urgent sins (avarice, lust, intemperance) are never closed. For Thompson’s alter-ego, a swashbuckling journalist named Raoul Duke, the vulgar, 24/7 Circus-Circus Casino was, ‘what the whole hep world would be doing on a Saturday night if the Nazis had won the war’ – a wisecrack that seems to make more sense than it actually does.

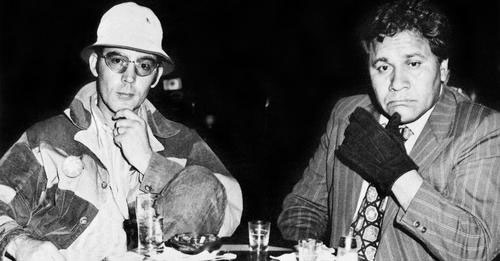

Duke and his sidekick, the 300 lb. ‘Samoan’ attorney, Dr Gonzo (in reality a portly Mexican-American activist attorney named Oscar Zeta Acosta[ii]), get dressed for action in ‘Acapulco’ shirts and make the trip in ‘The Great Red Shark’, a rented flash-trash Chevrolet convertible. They hit the road and their take-off drugs to the canticulum of, ‘Pleased to meet you – hope you guessed my name…’ and sure enough, it isn’t long before demonic forms begin to dance in the desert sky.

Thompson and Acosta take a break from their savage journey

Ben’s car in Leaving Las Vegas is not described; it’s any-car, a means of moving from home to bar to liquor store and finally from Sodom to Gomorrah. Ben is any-drunk; the office job he has been fired from is any-job. His clothes are LA dapper – ‘well dressed’ – the functional wardrobe of the life he led before his wife left him. Preparing to depart LA, he burns all personal possessions, all documents, all photos. Into the flames goes a cherished black leather motorcycle jacket, the same as one O’Brien actually owned, a wild-side signature garment for a late developer. Ben expects the five-hour drive to be difficult, probably ‘hellish’ (even without a Satanic Majesties’ soundtrack) and indeed it was. Since Ben isn’t going to Vegas to make an impression he will only don a loud, jungle-print party shirt towards the end of his visit.

The narrative of dissolution in both stories requires cash to be metabolized at a steady rate and, in true Vegas fashion, the meter never stops running. Raoul Duke plunders his advances from publishers and cheats on expense accounts, yet still skips out on hotel bills. Ben’s endless bender wildfires his severance pay and runs up credit card debts he won’t to be around to settle. For little more than walking-around money he unloads his car and Rolex but Vegas doesn’t care what way it comes as long as it gets there.

***

John O’Brien had gone through years of rejection slips before Watermark Press, a small-scale operation in Wichita Kansas, published Leaving Las Vegas in 1990. A few years later, the film rights were optioned and when British director Mike Figgis completed the movie it went on to receive multiple award nominations – four apiece from the Golden Globes, BAFTAs and Oscars – and grossed around fifty million dollars.

We’ll never know what O’Brien might have thought of it. On April 10, 1994, a few weeks after signing the contract, he shot himself in the head. He was 33 and had recently lost another day job, this one in a coffee shop. According to Gaylord Dodd, the founder of Watermark, it was a period when O’Brien was drinking up to a gallon of vodka per day.

The only novel he fully completed in his lifetime, Leaving Las Vegas features elegantly dark lines, strong characterizations and showstopper scenes. Even with its weak spots, the indulgences of a developing writer, it’s a cherishable book – not simply a reminder of lost talent. Other American fictions about alcoholism that became films, cautionary tales of broken lives like The Lost Weekend and Days of Wine and Roses, are nothing like it. Nor is there much in common with Charles Bukowski’s swaggering skid-row confessions despite chapters set in a similar Los Angeles underworld.

After sending Ben across LA on a farewell binge, O’Brien invests him with a shade of intricacy. When he comes to, face down on a public toilet floor with strange piss in his hair, Ben doubts that even an ‘existential pep talk’ by Albert Camus would redeem the utter failure of his life. We are to understand that Ben’s story is a bona fide Existential Crisis – not just another noir episode of loser-on-the-rocks. According to Camus, suicide is never the right solution and his pep talk would have encouraged Ben to accept the sniggering cosmic indifference of Existence, embrace its absurdity and carry on – not to happiness but to freedom. For Ben, oblivion is the only freedom O’Brien believes in.

LLV’s most compelling character is Sera, a stoic and hardworking hooker who provides our view of Vegas from an insider perspective: the undercurrents of the casinos, sardonic dealers, security thugs, easy marks and high rollers. She finds her own life’s absurd meaning in emotionally detached carnality and her romance with Ben is a Freudian, masochistic fusion of Eros and Thanatos. For a novel stiffened by candid and coarse sex, the only consummation granted to its lovers is a respite from loneliness.

If the outcome is predictable enough to be a let-down – the film version’s attempt to raunch it up is even worse. With what we now know about O’Brien’s life, it still underlines the loss his death brought to those who loved him.

***

As a Wild Turkey snow-cone and designer LSD-fuelled media-terrorist, Hunter Thompson would have in many ways satisfied Camus’ definition of ‘The Rebel’ – even the Metaphysical Rebel, who not only protests his own condition but the whole shitty mess of creation. When Thompson declared a guerrilla war-of-words on the Establishment, his excesses of alcohol, dope and felonious conduct were weaponized, the attributes of an enemy beyond reasoning, of the dangerously possessed.

He was just one of the hipper hacks who experimented with participatory reporting but took it up another level, turning the story’s lens onto himself. At the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago (where he claimed that cops had thrown him through a plate glass window), the Yippies’ provocations gave him ideas.[iii] There had been Mailer, of course, giving himself a third-person presence in The Armies of the Night, which documented the 1967 protest march on the Pentagon and let him mock his own radical intellectual celebrity. A more personal inspiration came from Ken Kesey and the Pranksters,[iv] who refined the trick of out-squaring the squares while hiding all kinds of unholy weirdness in plain sight.

Somewhere along the way Thompson pretended to abandon the profession of journalism, describing it as ‘a low trade and a habit worse than heroin’, a seedy world of ‘misfits and drunkards and failures’. He began to despair at actually doing the work, something he could only overcome through the foreplay of large advances, princely expense budgets and ritzier chemicals. He made no protest, however, whenever feted as a ‘New Journalism’ pioneer or one of the chic media outlets’ zeitgeist-busting celebrities, always hurrying to play the role on late-night talk shows.

For over 40 years he continued to dissect the establishment’s fearful and loathsome state, the Empire of the Senseless, the politicians and the powerful who owned them. When some of his best work was collected in a Rolling Stone anthology, a reviewer said he wrote ‘top-notch journalism, of course, but beyond that there is a depth, a truth, that runs through Thompson’s writing. It’s as if his investigative instincts apply not just to the story, but to his telling of it…turning the facts—and more than a few fictions—over in his mind, uncovering hidden facets and exposing every angle so that the readers could see the story at its very core.’[v]

The New Journalism’s innovation, according to Tom Wolfe, was to, ‘…take, use, improvise. The result is not merely like a novel. It consumes devices that happen to have originated with the novel and mixes them with every other device known to prose…the reader knows all this actually happened.’[vi]

In Fear & Loathing, ‘actually happened’ was stretched beyond absurdity and Thompson confided, ‘Only a goddamn lunatic would write a thing like this and then claim it was true.’ For the book’s ‘jacket copy’, an unpublished introduction, he explained Fear & Loathing with an almost restrained pride – ‘…although it’s not what I meant it to be, it’s still so complex in its failure…I can take the risk of defending it as a first, gimped failure in a direction that “the new journalism” has been flirting with almost a decade.’[vii]

Considered as a novel, its requisite qualities are slight – the cast of caricature extras and slapstick narrative roll precariously along the edge of chaos. Thompson even resorts to a little bum-Trip Advisor ‘travel writing’, exploring Vegas’ plasticine imitation of civilization and scabrous heart. This was hardly news to anybody but the book cut it as a metamorphic work for the jive talking duet of Duke and Gonzo, a pair of mind-fucked libertarian assholes who bring together the drollery of Gulliver’s Travels, badinage of Naked Lunch and brio of The Three Stooges. Literature has always had a soft spot for this kind of road journey teamwork, whether Don Quixote and Sancho Panza…Huck and Jim…Sal and Dean…or Bob and Bing.

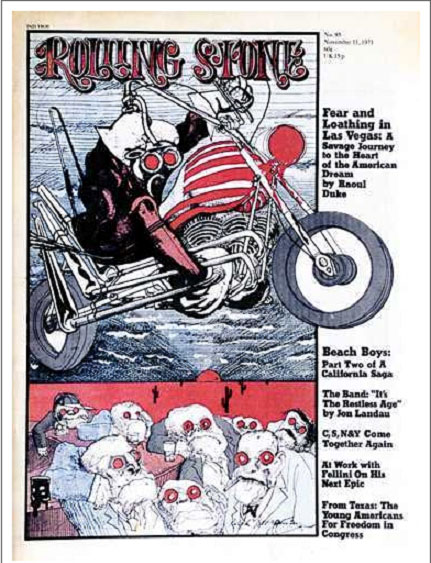

An assignment from the posh-jock magazine Sports Illustrated to ‘cover’ the Mint 400 desert motorcycle race required Thompson to produce 250 words worth of snappy photo captions. Instead, he spewed, quite literally, 2500 words – and Sports Illustrated rejected every one – along with his always immodest expenses tab.

At the time, Rolling Stone magazine was raking it in from music industry hustlers posing as patrons of dissidence and was still inspired by its unwashed Underground Press roots. Without hesitation, they snatched up the story and, in a moment of what could have been editorial madness, sent Thompson and his medicine chest back to Vegas to extend the wordcount by reporting on the National District Attorneys Association’s Conference on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs.

Thompson announced that he would no longer be taking the usual notes but using his ‘eye and mind like a camera…the writing would be selective & necessarily interpretive – but once the image was written the words would be final.’[viii] This shaky lean on Jack Kerouac’s instructions for spontaneous prose was soon abandoned. In the artfully hallucinated final draft, the motorcycle race and the conference were of less concern than the end of the Sixties and the squandered promise of the era. At the point of his final blundering getaway, Thompson / Duke pot-shots the guilty, starting with the psychotropic snake oil peddler Timothy Leary (‘there is not much satisfaction in knowing that he blew it very badly for himself, because he took so many others down with him.’); Sonny Barger for declining from uber-outlaw to moneygrubbing mobster; followed by the SDS / New Left countercultural killjoys and all the utopia-exploiting gurus, cult-mongers and mind-warpers he could think of.

The use of drugs by Duke and Gonzo is voracious and multi-layered, not so much getting stoned as ultra-intoxicated – with a side-car of semi-psychotic paranoia. Far beyond the mescal-soaked Day of the Dead visions of Malcolm Lowry’s Under The Volcano this was another literary original, an all-American Hieronymus Bosch portraying the hemorrhoidal ass-end of evolution.

First publication, first part in Rolling Stone, November 11, 1971

The relevance of Thompson’s subtitle “A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream” may echo An American Dream, Norman Mailer’s 1965 novel. Mailer’s Ubermensch protagonist Stephen Rojack (war hero, ex-Senator and posturing New York talk-show host) gets away with murder through a torturous intrigue linking politics, obscene wealth, police duplicity and the justice-proof veneer of celebrity. Its overwrought dialogue (Mailer in showy conversation with himself) and scenes of violence and transgressive sex are delivered, according to one study, by ‘stylized language, and an abundance of mythical, fairy tale imagery to evoke an exaggerated, dreamlike psychological fantasy’,[ix] which almost passes for a description of Fear & Loathing. But, even if Rojack was a self-caricature, just as Raoul Duke is for Thompson, Mailer trying to write comedy was a struggle he usually lost.[x]

It took until 1998, 27 years, before Fear & Loathing became a motion picture doomed by the direction of Terry Gilliam. Nominated for few awards, Johnny Depp’s impersonation of Thompson managed to win the only one – in Russia – and the box office came in $8,000,000 short of the production cost.

***

John O’Brien’s childhood and teenage years in the suburbs of epithetical Lakewood, Ohio were occupied by stamp collecting, planet gazing, avid reading and listening to Bob Dylan. The signs of a delayed rebelliousness included not attending his high school graduation ceremony and getting his diploma made out in the name of ‘John Dylan O’Brien’. He could still have gone on to university but instead married his girlfriend and set off on explorative road trips, short term jobs, time in Portland, time in Atlanta.

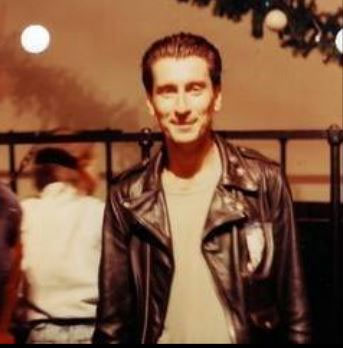

By January 1983, they were in Los Angeles and O’Brien’s arraignment had become that black leather jacket with a t-shirt and jeans – the utilitarian style of street punks in Hell’s Kitchen, the Booze Fighters on Market Street in Frisco and city-of-night hustlers all over America. For tough guys it meant protection from switchblades, truncheon blows, road rash, police dog bites – then became an edgy style for maverick film stars, pouting poster icons, a re-enactment of attitude and desire. Bobby Zimmerman adopted the look as an adolescent in Hibbing, Minnesota – ‘Just like Marlon Brando’. A poseur cliché already when given a kitsch new use by Joey Ramone and Bruce Springsteen, satirising a tribal lore of pseudo-primitive masculinity that had long since gone cold.

John O’Brien

To match his new look, O’Brien had graduated from Coca-Cola to Wild Turkey (what else?) and the thirst for freedom he had discovered in his bedroom books and the road-wise rhymes of Dylan did little to warn him about what could often be alcohol’s self-fulfilling curse.

In many of his photos, O’Brien is charmingly gawky, smiling and self-assured like a clued-up dude with drowned uncertainties. It makes you wonder what it would have taken to save him if a credible promise of fame, fortune and literary recognition turned out not to be enough.

Seven years later, with a drinking habit well underway, O’Brien had the start of the writing life he had dreamed of – publication of his first novel, nearly completed drafts of two more and agency representation by Ray Powers at Marje Fields. Leaving Las Vegas could well have remained a cult first novel that never made it into paperback except for Powers’ persistence to secure a film option. Another agency, the elite William Morris, tried to lure him onto their books and Laura Ziskin, producer of Pretty Woman, offered a commission to screenwrite a new version of Days and Wine and Roses.

When Nicholas Cage agreed to take the role of Ben in the movie he said O’Brien’s suicide had been the deal-clincher. ‘It wasn’t just this character. It was layered now. There was irony.’ Suicide’s ironic provenance may not appeal to everyone but real irony would arrive when Cage’s glum, hammy and medically unrealistic portrayal of a dying drunk won an Academy Award. The movie treatment added its own backstory, making Ben a Beverley Hills-cruising scriptwriter whose drinking destroys his talent and politesse in the presence of pretty women. What seems like a plot lift from The Lost Weekend was an ill-judged attempt to make ‘Ben’ a more glamorous version of his creator.[xi]

The suggestion that O’Brien wrote Leaving Las Vegas as a ‘suicide note’ is untrue according to his sister Erin.[xii] The comment originated in a letter she had sent to Cage, which the film company then exploited. Powers, who was for a couple of years also my agent, claimed O’Brien phoned him only days before he died and during the call said, ‘I am Ben’ but that’s hardly the same thing.

***

Even if Hunter Thompson’s teenage kicks didn’t include hot rods, motorcycle jackets and greased quiffs, his troubles with the law ran from truancy, underage drinking and vandalism to car theft and burglary. Thompson’s father died when he was only 14 – fatherless, he turned to books for formative influences and found Sebastian Dangerfield, the atrocious hero of J P Donleavy’s The Ginger Man, and the colourful local lore of Kentucky’s antebellum decadence. When he should have been preparing for his final high school exams he was locked up in juvenile detention.

In 1964, after several years scratching a living out of freelance reporting, Thompson arrived in Ketchum, Idaho to research an article on the suicide of Ernest Hemingway, a writer he admired so much that he had (like Joan Didion, one of his essayist / journalist contemporaries), typed out pages of Hemingway’s prose to improve his own writing technique. Thompson’s theory of why Hemingway shot himself – a lack of political commitment and confusion about grey areas in modern ethics – doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Locals who knew Hemingway described the decline of a self-publicised man-of-action who was no longer able to carouse, go hunting or be the life and soul of the party, the lion in the room.

A few years later, Thompson discovered his own ‘Ketchum’ in Woody Creek, Colorado and used royalties from Hell’s Angels, his first book, to purchase Owl Farm. The farmhouse was remote enough he could wander out onto his porch, stark naked, and let off a few rounds from his .44 Magnum without disturbing the neighbours. Where Hemingway had hunted the backwoods for ducks, Thompson hunted for bigger bangs and, just as Hemingway cozied up to war and bullfighting, Thompson found his own ways to play close to the fire. Back in San Francisco he had taken drug-winged midnight runs down the winding coast highway on his motorcycle; ‘…that’s when the strange music starts, when you stretch your luck so far that fear becomes exhilaration and vibrates along your arms. You can barely see at a hundred…’.[xiii]

With the Hells Angels (and without the fucking apostrophe), Thompson found the real edition of his teenage rebellion, impelled by beer, pills, weed and velocity, but all grown up and ready to rumble. They cut a slovenly piratical dash that he wisely avoided by sticking to his shore-leave casuals. Eventually, he annoyed a group of Angels enough that they stomped his ass, an event he may have provoked to take centre stage in his book’s conclusion. As Thompson told it, he had been horsing around with one of the Angels and got him in a bear hug, whereupon the others piled in and broke his nose. Only just saved from having his head caved in with a rock, he drove himself to the hospital.[xiv]

According to Sonny Barger, the president of the Angels’ Oakland chapter, Thompson had intervened when a club member slapped his own girlfriend. When a few members roughed him up and ordered him to leave, he ran to the police and filed a complaint. ‘Hunter turned out to be a real weenie,’ wrote Barger. ‘You read about how he walks around his house now with his pistols, shooting them out of his windows to impress writers who show up to interview him.’ [xv]

Norman Mailer’s weakness for subtly self-reflecting hyperbole was apparent as he described a certain type of self-dramatizing writer, compelled to live in a ‘psychic terrain where he has to be brave beyond his limits’ or else he will have to ‘make another reconnaissance into / death.’[xvi] While the subject of this could have been either Thompson or himself, it was in fact Hemingway. Mailer and Thompson spent time together while covering Rumble in the Jungle, the Ali vs. Foreman boxing match in Kinshasa. Mailer, a drinker of some renown, was in awe of Hunter’s constitution, his taking more drugs ‘than any good living writer’ and drinking more beer ‘than all but a hundred men alive.’[xvii]

Anecdotal accounts by Thompson’s girlfriends, buddies and guests at Owl Creek suggest that he welcomed the start of each day – around mid-afternoon – with a glass of Chivas Regal, strong coffee and the first of many Dunhill cigarettes. A taxing schedule of cocaine, grass, Heineken, margaritas, chartreuse, LSD, champagne and Wild Turkey would then follow. Margot Kidder was a witness to this stamina when he visited her and husband Tom McGuane in Key West. Thompson and McGuane agreed to find out who could take the most drugs without dropping dead. ‘I was very upset. I was screaming “Hunter! Hunter! You’re going to kill my husband!”’[xviii]

When Thompson said his intake of booze and narcotics was obviously exaggerated or else he couldn’t still be alive no one actually believed him. Nevertheless, he would always be considered a Falstaffian hellraiser and altered-state connoisseur and never a pitiful drunk or sad junky. Few seemed to notice that something might be missing – like the time he ordered a pizza ‘with everything’ and after opening the box, registered genuine disappointment, saying, ‘There’s never enough everything.’

In 1978, when The Great Shark Hunt, his first collection of press and magazine articles was ready for publication, he wrote the introduction while sitting in his publishers’ 5th Avenue, New York office. He was 40 and teasingly styled his copy like a suicide note, wondering whether his time was over and he should run over and leap out the nearby 28th floor window. ‘I have already lived and finished the life I planned to live’.

Twenty seven years later, Thompson would be struggling to walk after first breaking a leg and then having hip and back operations. For the back surgery he was required to withdraw from a lifetime of constant alcohol use. The doctor had him placed in an induced coma to make this more bearable but it was only partly successful, leaving him in pain, distressed, sour tempered and never likely to ever again be the life and soul of the party.

He was inspired to compose another suicide note, one which he gave a both literal and symbolic title – “Football Season is Over”. The 2004/5 NFL season had just finished and Thompson managed to host a small gathering of family and friends to watch the televised Superbowl game. Football was one thing he could love in an old fashioned American way – he had begun his career as a sportswriter and at Rolling Stone his beat listing on the masthead (as Raoul Duke) was ‘The Sports Desk’.

The note had a poetic lilt.

‘No More Games. No More Bombs. No More Walking. No More Fun. No More Swimming. 67. That is 17 years past 50. 17 more than I needed or wanted. Boring. I am always bitchy… No Fun – for anybody. 67. You are getting Greedy. Act your old age. Relax – This won’t hurt.’

When he put the barrel of a .45 calibre pistol into his mouth on

February 20th, it was more than a solution to pain and despair – it was also an act of rebellion – against the doctors, the indifference of their science, and the closing trap of his body. It was also on behalf of the people who, in spite of

everything, remained closest to him and whose lives he was making

miserable. When finally cornered, with no pleasures left to him but guns &

bullets, the only option was to shoot his way out and nothing left to shoot but

Existence.

***

The epigraph is from “For the Love of Dying”, Selected Poems of Malcolm Lowry, City Lights Books, 1962.

[i] “The Landscape of Luxury” in Occupying Architecture, ed. Jonathan Hill, London, Routledge, 1998

[ii] https://evergreenreview.com/read/the-marginalization-of-oscar-zeta-acosta/

[iii] https://www.history.com/news/yippies-1968-dnc-convention

[iv] https://realitysandwich.com/ken-kesey/

[v] “HUNTER S. THOMPSON, THE METHOD AND THE MAN: ‘FEAR AND LOATHING AT ROLLING STONE”, Christel Loar, February 2012. https://www.popmatters.com/153852-fear-and-loathing-at-rolling-stone-2495891562.html

[vi] The New Journalism, Tom Wolfe, “Like a Novel”, Picador, London 1975. p.49.

[vii] Hunter Thompson, “Jacket copy for Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas”, in The Great Shark Hunt, Summit Books, 1979. p.21-2.

[viii] Paul Perry, Fear and Loathing / The strange and terrible saga of Hunter S. Thompson, Thunder’s Mouth Press, New York, 1992, p.???

[ix] Andrew Gordon, An American Dreamer. A Psychoanalytic Study of the Fiction of Norman Mailer, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, London, 1980.

[x] Coincidentally, perhaps, An American Dream concludes in Las Vegas, where Rojack flees to

gamble up the money to pay his debts and to make peace with his ghosts.

[xi] For a shrewd critique of the film see “The Lost Evening” by August Kleinzahler in his collection of essays, Cutty, One Rock, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York, 2005. p.53.

[xii] Erin O’Brien is a journalist, novelist and blogger who edited several of her brother’s left-behind works for publication, including the nearly finished novel The Assault on Tony’s, which Grove Press published in 1996.

[xiii] Hunter S Thompson, Hell’s Angels, Allen Lane – The Penguin Press, London, 1967. p.276.

[xiv] Paul Perry, Fear and Loathing / The strange and terrible saga of Hunter S. Thompson, Thunder’s Mouth Press, New York, 1992, p.158.

[xv] Ralph Sonny Barger, Hell’s Angel, Fourth Estate, London 2000. p.125.

[xvi] Norman Mailer, “Punching Papa”, in Cannibals & Christians, Andre Deutsch, London, 1967, p.156.

[xvii] Norman Mailer, The Fight, Penguin, London, 1991, p.120.

[xviii] Quoted by E Jean Carroll in Hunter – the strange and savage life of hunter s thompson, Simon & Schuster, London, 1994. p.212.