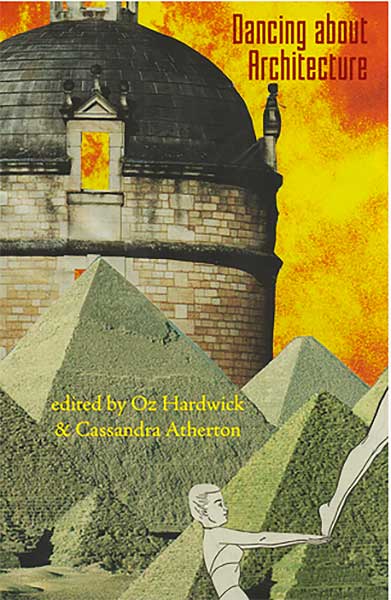

Dancing About Architecture, edited by Oz Hardwick and Cassandra Atherton

(Mad Hat Press)

Dancing about Architecture is an anthology of contemporary ekphrastic poetry. ‘Ekphrastic’, for those who don’t know, is a term generally used to describe a verbal description of a work of art, but there’s more to it than that, as we’ll see later. The title of the book comes from the unattributed saying ‘writing about music is like dancing about architecture’. It’s usually taken to imply the absurdity of both, whereas, in fact, writing about music can, I hope, be a way to open people’s minds to it and, if more people danced about architecture, perhaps people would pay more attention to their living-spaces. And it has been done. Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadishe Ballett set out to illustrate the design ideals of the Bauhaus and, in the 1970s, Trisha Brown’s Roof Piece, which had several solo dancers performing on roof-tops in New York, drew its inspiration from the buildings of that city.

I suppose you could describe both those works as ‘ekphrastic ballets’, as, although the term ‘ekphrastic’ is most often applied to poetry, it can be applied to other art-forms to. And, as editors Oz Hardwick and Cassandra Atherton point out in their introduction to this book, the original eighteenth century use of the term applied not only to visual art but to any work of art in any medium. You can make ekphrastic art based on literature, Millais’ Ophelia, being based on Shakespeare, being a case in point. To go back to that quote and mashing it up, one could even make music about architecture. The composer Iannis Xenakis was both a composer and an architect and applied similar processes to both. His orchestral work Metastasis (1952-53) was based on the Phillips Pavilion, a structure he’d collaborated on with Le Corbusier.

One great feature of this book is how all the poets included in it have provided commentaries on their poems. It may be stretching things a little to consider them a representative sample, but, since there are fifty-six of them, drawn from all over the world, it’s interesting to consider the preoccupations they share in common (or not). Sarah Holland-Batt, Cassandra Atherton and Oz Hardwick all use the past as a filter through which to see the present. Holland-Batt has based her poem on a picture by Fairfield Porter, whose work, as she says in her commentary, ‘seems to memorialise a vanishing, utopian form of childhood and adulthood in spacious homes and green spaces that is increasingly only accessible to the privileged classes’. Cassandra Atherton meditates on a Hiroshima that must be ‘reimagined, represented and invoked’ to try to prevent it from happening again. Hardwick’s meditation on 1970s electronic music and the space race invokes an ‘ever-expanding hauntological apprehension of a future that never was’. Pascale Petit, in her commentary, strikes a less wistful tone, enthusiastically describing the subject of her ekphrasis (Rebecca Horn’s Concert for Anarchy) as ‘flouting the cultural setting [of the art gallery] and upending our civilisation’. Leo Boix literally upends South America, basing his poem on Uraguayan artist Joaquín Torres-García’s América Invertida, a map of South America with the south at the top. It is, says Boix, ‘a streamlined manifesto for a South American youth.’ Edwin Stockdale and Jane Yeh’s poems touch on the life of the LGBTQ+ community. Stockdale’s prose poem reflects on the life of bisexual British monarch Edward II and references Derek Jarman’s eponymous film. Jane Yeh’s poem explores the intriguing work of Claude Cahun, the surrealist artist and writer, and its exploration of identity and rejection of binary gender. Feminism is an undercurrent running through many of the poems, becoming explicit in several: for example, Helen Ivory critiques the Pre-Raphaelite view of women (‘I wanted to write the poem in a tone that I know that Rossetti would hate’) and Mags Webster provides us with a homage to Plath in the form of a sestina based on a Henri Rousseau painting (something Plath herself did).

In her diary, Virginia Woolf reports a conversation she had with TS Eliot. She suggests they were not as good at what they were doing as Keats. Eliot disagreed, adding ‘we’re trying something harder’. I don’t remember any poets in this anthology name-checking Eliot or Ezra Pound, but Keats does get a mention, as does Romanticism generally (though not, interestingly, Blake – a poet who definitely would’ve garnered a mention fifty years ago). To take one example, Anne Caldwell’s invocation of a painting of Shackleton’s Endurance has inevitable echoes of Coleridge and Melville about it (of course, I’m talking preoccupations here, not language and structure, although she does quote The Rime of the Ancient Mariner). Rimbaud gets a mention (I’m surprised his name doesn’t pop up more often), as does Mallarmé. It made me wonder what with all the Romantic, Modernist and post-Modernist impulses that went into making the poetry here, you could almost call it post-Everything. To go back to Woolf and Eliot, you could say all the hard work has been done, with the result that a poet writing today now has a whole range of different approaches to chose from. (Not that you have to: there is always the option, still, to ‘make it new’, as Pound put it).

To pick a few random examples. Ian Seed’s Secondary Education, based on a black-and-white photograph of himself running in a cross country race at school, has an almost Angry Young Man feel. Jennifer Harrison writes with a voice that reminded me of Diane di Prima. Michael Leong’s poem, more experimental, is based on an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in New York and was created using words and punctuation from the exhibition catalogue. Jane Burn’s contribution is a celebration of the work of artist Victor Pasmore: both his abstract art and the Apollo Pavilion, a piece of public art in Peterlee, Co. Durham. The layout of the poem on the page ‘suggests both the building’s plan and his abstract artwork – the milder curves and the harsher straights’. Burn, incidentally, isn’t the only poet to draw on architectural art on a grand scale: Rupert Loydell’s ‘Barjac’ takes us to Anselm Kiefer’s vast exhibition complex in the South of France. It’s prefaced with a quote from Danièle Cohn’s book, Anselm Kiefer Studios: ‘A palette cannot become a bird just because it is adorned with wings with discernible feathers.’ The idea is taken up in the poem and it’s one that resonates playfully with the whole idea of ekphrasis.

It’s interesting, too, to see how different poets approach the challenge of writing ekphrastic poetry. Some approach it quite formally. Bob Beagrie, for example, says that ‘ekphrasis aims to illuminate meanings within an artwork through written description.’ Simon Collings, on the other hand, says ‘my text … doesn’t seek to represent the original, but to record my reaction, however personal and subjective that might be.’ There is a whole spectrum of possibilities between these two approaches: I guess poets have to find the way that works for them. Myself, I’d add that whatever approach a poet takes, one measure of the success of an ekphrastic poem is the extent to which it stands up as a work of art in its own right, without the reader feeling a need to refer to what it’s based on – although, intrigued by the poem, they might wish to. I should add that both Collings and Beagrie, in their different ways, achieve this.

Several poems reference music: Debussy, Stravinsky, Copland and Hawkwind all get a look-in. Paul Munden’s evocative poem based on Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto, ‘The Memory of an Angel’, had me wanting to stick the music on. However, I was worried by one phrase in his commentary: he describes Berg as having had ‘some Nazi sympathies’. This is, I think, more than open to question. It has been pointed out that Berg used a slogan associated with the Nazis in the scetches for the Violin Concerto: ‘Frisch, Fromm, Fröhlich, Frei’ (or, in English, ‘fresh, pious, happy, free’). He intended to base the character of each movement on these moods. Using some extra-musical scheme like this was typical of Berg: he was fascinated by numerology, ciphers and symbolism (he was decades ahead of the hidden messages played backwards in LP tracks craze). However, in the sketches, he uses the words of the slogan in reverse order, something he would typically do to register his disapproval! Then there’s the case of Berg’s use of language in relation to one of the characters in his second opera, Lulu. Berg died leaving it unfinished and his teacher, Schoenberg, refused to complete it because he considered parts of the text offensive. However, Schoenberg’s friend Erwin Stein (both men were Jewish) said he thought Berg had been merely ‘thoughtless’ and Friedrich Cerha, the composer (and fervent anti-Nazi) who did complete it, was of the opinion that Berg had written what he did because it reflected what real people would have said at the time it was set and, by so doing, intensified the dramatic realism. The philosopher – and composer – Theodor Adorno, who studied composition with Berg, said of him that he ‘rejected the anti-Semitism to which his Viennese surroundings could easily have tempted him’. Add to all this the fact that the Nazis considered his work to be ‘degenerate’ (on account of its use of atonality and his associations with Jewish composers) and the case for Berg having Nazi sympathies looks pretty thin. It needs to be said, though, that this is merely one quibble in a book featuring over fifty poets with a wide range of reference.

One of the side effects of reading this anthology, I’ve discovered, is how you start noticing ekphrasis where you’ve never noticed it before. A lot of ekphrastic poems hide in plain sight (I leave it to the reader to discover a few). Nevertheless, there’s even more to it than that: as well as being able to read the poems, we learn a lot about the featured poets and what makes them ‘tick’. The ekphrastic angle probably intensifies this: the poets get to talk not only about themselves, but also about other creative minds that have intrigued or influenced them. I must stress that it wasn’t always the case, but I was interested to discover how often the commentaries on the poems I liked least tended to focus on the poet’s writing practice, whereas, in the commentaries on the poems I enjoyed most, the poet enthused not so much about their practice, but their preoccupations. I guess this is to be expected: good technique alone does not make for good poetry, whereas an intense connection with subjects which resonate with the reader does. And there are more than enough poems in this book that achieve this. A good read, then, not only for the poems themselves but for the insights into how they came to be written.

Dominic Rivron

.