By ANDREW DARLINGTON

When Waylon Jennings asked ‘Are You Sure Hank Did It This Way?’ he was referencing an iconic figure in the mythology of Americana. Some claim Hank Williams was the first Rock ‘n’ Roll star. Of course, he predates the Rock era – born 17 September 1923, he died of heart failure, maybe induced by an overdose, in the back seat of his car on the way to a gig, 1 January 1953 – at the age of just twenty-nine. The ‘hillbilly Shakespeare’ died with snow in his headlights. But his life anticipates the doomed arc of the Rock lifestyle. As music-journalist historian Lillian Roxon points out, ‘he was tall, dark and good-looking, a beautiful, gentle singer. And he wrote literally hundreds of hits.’

As I was growing up through the decade of the sixties, I was aware of Hank’s ghost presence. Australian singing star Frank Ifield had his second UK no.1 hit – from 8 November 1962 for five weeks, with ‘Lovesick Blues’, which had given Hank one of his biggest successes over ten years earlier. It was written by Emmett Miller in 1928, but provided Hank Williams with his breakthrough hit. While Ray Charles took Hank’s ‘Your Cheating Heart’ to a UK no.13 in the December of 1962. Elvis Presley issued his own version of the song shortly after.

Later, towards the end of the decade, tipping over into the seventies, when Country-Rock became vogue, musicians in interviews began to reference Hank’s music as an influence, and Hank became a trendy name to drop. As in Waylon Jennings song, it was Hank Williams who formed the lodestone for authenticity. It might have been the cheery reassuring radio hits of Red Foley and Eddy Arnold that outsold the fiercely insurgent music of Hank Williams while he lived, during the 1940s and early-1950s, but it is Hank who still reaches out to us more strongly today.

The bare bones of his story are clear, born Hiram Williams in the rural Bible Belt Alabama dirt-road logging settlement of Mount Olive, he was a third but second surviving child, and he suffered from spina bifida that caused him the severe lifelong pain he self-medicated with drug abuse and alcoholism. So much is undeniable. Yet there’s much that is not documented, as his scrupulous biographer Colin Escott freely acknowledges, ‘Hank’s early career is largely available to us only as an accretion of fragments, and the picture doesn’t begin to sharpen for several years.’ And where there are several different accounts of an event, Colin presents them equally, allowing the reader to draw their own conclusions and decide which is most likely. What was considered Folksy Hillbilly music was seen as not worth serious critical attention at that time, even to the extent that respect was grudgingly granted to Jazz or Blues. Nashville was not yet the Nashville we recognise today. What Hank termed Folk music ‘from a mean bottle’ was an uncouth disreputable thing, despite his protestation that the ‘songs express the dreams and prayers and hopes of the working people.’ Others would call it the white man’s Blues.

Hank had a difficult relationship with his stern acid-tongued but strong-willed mother, the 200-pound Lilybelle. She ran a boarding house in Greenville or – some claimed, it also functioned as a bawdy house of ill-repute. His absentee father, Elonzo ‘Lon’, suffered long-term after-effects from Great War injuries, and was frequently institutionalised. Yet during the Depression poverty years young Hiram had to help supplement the family income. Too frail and spindly to work, he learned to survive by his wits. Augmenting his precarious finances by cutting school to shine shoes, sell peanuts, and go sidewalk busking on hoedown fiddle or on the $3.50 guitar his Mom had bought him at age eight. His cunning scams involved swindling punters, and – at eleven while living in a boxcar, filching moonshine booze from his uncle Walter McNeil.

They had no radio or phonograph, but once in larger Montgomery town, Hank encountered black street musician Rufus ‘Tee-Tot’ Payne, from whom he acquired the lazy Blues swing feel and sock rhythms that permeate Hank’s best work. With Lilly as the motivating force, he sang at talent shows, and by the late months of 1936, by busking outside Radio Station WSFA he became ‘The Singing Kid’ on air. By 1938 he had his own group which would become the Drifting Cowboys. He also became Hank – which sounded more hillbilly or western than Hiram, and he got to hear Roy Acuff’s grieved singing and resolutely Appalachian music, a thick-textured fabric of fiddle and steel guitar. In Hank’s pantheon, it was now Roy Acuff – then god! Hank’s emerging style resembled neither the south-eastern harmonies nor the Western Swing from points southwest, but carried a commitment level innovative to Country music, with rhythms slapped out on the stand-up bass.

For Hank, there were songs, hooch, Juke Joints, hotels, honky-tonks, an acetate, Texas, his parents’ divorce, both parents remarrying – Lilly twice, concerts with no amplification or drums, just steel guitar and stand-up bass. And they worked comedy routines into their set. He played Red Foley’s sentimental ‘Old Shep’ – a later favourite of young Elvis Presley, and he sold his own first composition – ‘(I’m Praying For The Day That) Peace Will Come’ for a one-off $25 in December 1943. His band boarded over at Lilly’s – who astutely docked their pay accordingly. Unfit for conscription Hank sporadically worked the shipbuilding yards during the war years.

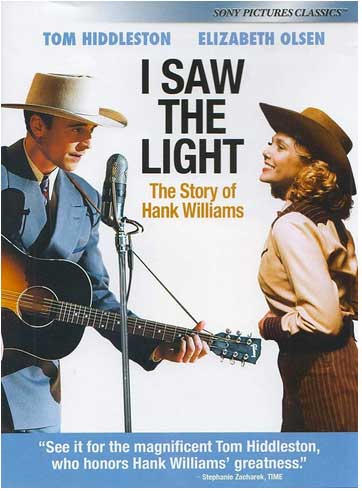

‘Are You Sure Hank Did It This Way?’ asked Waylon Jennings. The movie I Saw The Light (2015) directed and written by Marc Abraham, was based on Colin Escott’s original book Hank Williams: The Biography. There had been Ray (2004), the Ray Charles biopic starring Jamie Foxx in the title role, and Joaquin Phoenix as Johnny Cash in I Walk The Line (2005), as well as several movie takes on the Elvis Presley story. Hank Williams was the obvious subject for a similar project – a pivotal music figure, not quite Rock ‘n’ Roll, but with enough of the sex and drugs content to qualify, as well as the Buddy Holly-Jim Morrison element of the tragic early death. Colin’s book was revised, updated, and republished as a ‘Now A Major Motion Picture’ tie-in, with an iconic jacket-photo of British actor Tom Hiddleston in Hank guise carrying a guitar case down the steps of a beat-up hotel stop-over. Hiddleston is good, but the real Hank Williams had a more hungry razor-cut profile, a gaunt stray-cat look with a haunted harried energy driven by his personal demon. What Gavin Martin calls a ‘bony, weasel-faced guy’ with a ‘manic, pill-eating grin’ (Record Hunter, October 1990).

Hank’s first wife, Audrey Sheppard Williams – played by Elizabeth Olsen in the film, was already married when they met, but was as strong-willed and as single-minded in promoting Hank’s career as Lilly. Where Hank was too embarrassed to approach Fred Rose – of music publisher Acuff-Rose, it was Audrey who approached him in a hotel lobby and badgered him into signing Hank as a songwriter. So Hank found himself caught up in a tempestuous relationship between two feuding women, wife and mother! For Hank, his way of dealing with life’s problems was to go on a binge, resulting in his first rehab for alcoholism at the Alabama sanatorium as early as 1945.

But his career was on the up. Over the next few years, Molly O’Day recorded four of Hank’s songs. While Rose had his memory jerked by his secretary, and – acting for New York Indie label Sterling Records, he arranged for Hank to record for a one-off no-royalties session fee in Nashville’s WSM studio with a group of musicians called the Oklahoma Wranglers. It resulted in Hank’s first 78rpm single ‘Calling You’ c/w ‘Never Again Will I Knock On Your Door’ (January 1947, Sterling 201). Rose was to become to Hank Williams what George Martin would be to the Beatles, editing, advising, making suggestions, polishing the raw material of his songs into the finished records.

Although credited to Hank Williams & His Drifting Cowboys, the third single was cut with the scratchy country fiddles of studio musicians. And after two shots of largely spiritual material, its barroom whiskey-drinking lyric was tastefully amended at Rose’s behest, and the hard-bitten raw unornamented ‘Honky Tonkin’ ‘stayed in one chord for fifteen-&-a-half of its sixteen bars,’ and established its drum-less rhythm on guitar in the way that Johnny Cash would do. It was flipped with Hank’s rewrite of ‘Wabash Cannonball’ called ‘Pan American’ (May 1947, Sterling 210). The single climbed to no.14 on Billboard magazine’s Country Music Chart.

Hank was not an agreeable human being, he was unreliable, given to arrogance, he was manipulative, selfish, frequently unfaithful, given to violent outbursts, and he caused trouble wherever he found himself. As Derek Bull points out, ‘he needed uppers to get him going, downers to put him to sleep and there was booze to kill the pain.’ Hank had a deep-seated need for a strong woman to lean on, and Audrey had her own ambitions to be a singer, despite lacking any vestige of talent. They fought, but found time to conceive Hank Jr too! And all the while, he was building a fiercely loyal local following on the brink of going further. Audiences loved him – drunk or sober. Fred Rose took Hank’s rough acetates to Steve Sholes, who would later sign Elvis to the major RCA label, but he was not impressed. So, Rose went to Frank B Walker, who’d once signed Bessie Smith for a ‘race records’ subsidiary, at the newly-formed MGM label.

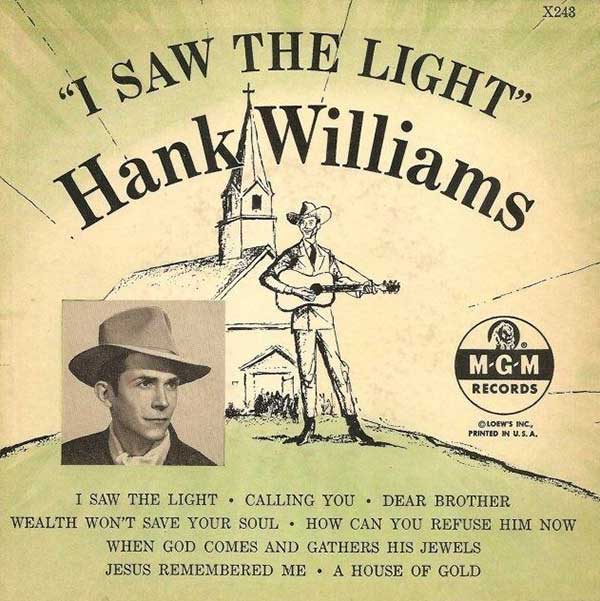

Hank’s first MGM session (21 April 1947) took place at Nashville’s Castle Studio and used Red Foley’s band playing and calling the vocal responses. It resulted in ‘Move It On Over’ c/w ‘(Last Night) I Heard You Crying In Your Sleep’ (6 June 1947, MGM 10033), issued on the big yellow record label adorned with the movie-lion logo. Looking back to ‘Tee-Tot’ Payne, the song reconfigured a basic twelve-bar Blues structure, with a pure Hank lyric about sleeping in the doghouse, ‘move over good dog, ‘cause a mad dog’s moving in.’ This time the single climbed to no.4 on the Billboard chart. A third track cut at the session – ‘I Saw The Light’, was a gospel remake that the label held back, although Rose’s vigorous marketing of the sheet music meant that a version by Roy Acuff was released before Hank’s own!

Things were put on temporary hold by a Musicians Union strike, and Hank went on a long drunk downward spiral. The Union saw the success of record sales and radio stations air-playing records as taking bread from the mouths of honest working musicians, in much the same anti-tech way that the advent of cassettes allowed the free-taping of music from radio, or MP3s permitted file-sharing. It was an attempt to hold back inevitable changes in the way that music was distributed and enjoyed. Although it squeezed some temporary concessions, it could not contain the deluge. Meanwhile, MGM bought up the Sterling masters, and Hank charted with a re-recording of ‘Honky Tonkin’’ (MGM 10171).

‘Are You Sure Hank Did It This Way?’ asked Waylon Jennings. Hank got a career boost by appearing on Shreveport’s ‘Louisiana Hayride’ on KWKH, a launching site where Webb Pierce, Faron Young, Johnny Cash, Elvis Presley, Slim Whitman and Johnny Horton would also get vital first breaks. It was there he performed his revival of ‘Lovesick Blues’, flecked by yodels and little flashes of falsetto. Where he’d first heard the 1922 song is dubious, although Escott speculates it was from a recording made in 1939 by Rex Griffin, the man who wrote ‘Everybody’s Trying To Be My Baby’ as done by Carl Perkins… then the Beatles.

Against everyone’s advice, Hank hastily recorded ‘Lovesick Blues’ during the final half-hour of an unsatisfactory session in Cincinnati, and it was issued 11 February 1949, flipped with the original Sterling cut of ‘Never Again (Will I Knock On Your Door)’ (MGM 10352). By 7 May the single was no.1 on the Billboard chart, and it stayed on the chart for no less than forty weeks, eleven of them at pole position. Hank celebrated by buying a second-hand 1948 seven-seater Packard sedan. To journalist Derek Bull ‘country (music) had relaxed into a rut of complacency, enjoyed mainly by white adults. The arrival of Hank Williams on the scene gave country a charge of excitement that meant it would never be the same again’ (in Record Collector magazine). By the time Hank recorded ‘Lost Highway’ – ‘I’m a rolling stone, all alone and lost, for a life of sin I have paid the cost,’ he was snorting nasal inhalers fortified with Benzedrine. Beat Generation writer William S Burroughs was another to find this a convenient high.

Hank had set his heart on appearing at the Grand Old Opry, although they held out on him. ‘Wedding Bells’ c/w ‘I’ve Just Told Mama Goodbye’ peaked at no.2, and later the same year Hank toured with Ernest Tubb, Red Foley and hillbilly comedy-turn Minnie Pearl, until the Grand Ole Opry could no longer ignore him. He was introduced on the Ryman Auditorium stage by Red Foley, 11 June 1949, and was formally hired a month later – with a new Drifting Cowboys line-up.

He’d broken through with two lucky songs from other writers. But he knew he must stand or fall on his own songs. And it would be there that he ‘invented’ himself. Hank was a wild card, for sure. He wrote at odd times, on a bus, waiting to go on stage, in a friend’s house, jotting down lyrics as they occurred to him, scribbling notes onto scraps of paper. He played rudimentary chord changes with a Blues tone. He insisted on nothing too intricate. To Escott, ‘he cast the highs and lows of everyday life in terms that were simple enough to register quickly over a car radio or jukebox, yet profound enough to bear repeated listening. His songs were the true-to-life Blues. Any art form at its best has the one-on-oneness of physical intimacy, and that’s what Hank brought to Country music.’ No jazzy notes. Simple and direct.

Inevitably there are stories that Hank borrowed song ideas, that he bought lyrics – particularly from a young writer called Paul Gilley (who died by drowning aged just 27), or that he adapted titles from other sources. He bought all rights to the bare bones of ‘Long Gone Lonesome Blues’ for $500 from a certain Vic McAlpin. All of which may well be true, yet what is more vital is that he unmistakably adapted and personalised his repertoire around his own persona. When it came to writing a song, he said, if it ‘takes longer than thirty minutes or an hour, I usually throw it away.’

Although it was issued – 8 November 1949, as by Hank Williams With His Drifting Cowboys, ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry’ c/w ‘My Bucket’s Got A Hole In It’ (MGM10560) was recorded in the Cincinnati Herzog Studio, with members of the Pleasant Valley Boys (Zeke Turner on lead guitar, Jerry Byrd on steel guitar, Louis Innis on rhythm guitar, plus fiddle-player Tommy Jackson and bassist Ernie Newton). The radio-play side was the old up-tempo Blues ‘My Bucket’s Got A Hole In It’ – which vaguely suggests some frustration metaphor for something more than just beer. While seldom can sadness have been caught with such aching melancholy as it is on ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry’, etched in simple but evocative images of the silence of a falling star, the lonesome whippoorwill too blue to fly, the midnight train whining low as time goes crawling by. It hit no.2 on the chart to establish him beyond doubt as the hillbilly poet, ‘his ability to merge earthy vernacular, bluesy melodies and the bleak lore of his Baptist background turned the popular song into the mouthpiece of the disenfranchised’ (Gavin Martin).

Hank scored his first syndicated radio series – Hadacol’s ‘The Health & Happiness Show’ in October for WSM, an ironic title as ‘Hank never had much of either’. It was recorded on 33-&-a-third sixteen-inch discs, leaving gaps for the advert slots to be inserted, and sweetened with shots of self-deprecating cracker-barrel humour. Hank began to wear Nudie Cohen suits, precursors to Elvis’ gold lamè and Gram Parsons rhinestone marijuana design suit. He toured American bases across divided Germany, with Red Foley (whose ‘Chattanoogie Shoeshine Boy’ held Hank’s ‘My Bucket’s Got A Hole In It’ from the no.1 spot!). But he was glad to get back to familiar America! where Hank made a point of playing his own records on the jukebox of every truck-stop and Diner they pulled into, as a means of self-promotion. He finished 1949 as second only to Eddy Arnold as the year’s biggest-selling Country star.

By his next recordings Hank had now fine-tuned his signature sound, using his regular road-band instead of session musicians, with Hank and Fred Rose evolving their intuitive studio relationship. For ‘Long Gone Lonesome Blues’ (b/w ‘My Son Calls Another Man Daddy’, MGM 10645) he took the hallmark vocal yodel-tricks from ‘Lovesick Blues’ but remodelled them into a song of startling originality, reshaping a country homily about finding an ice-cold suicide river, and ‘I’m goin’ down in it three times, but Lord, I’m only comin’ up twice.’ It – and ‘Why Don’t You Love Me (Like You Used To Do)’ (b/w ‘A House Without Love’, MGM 10696) recorded at the same session, took him back to the no.1 position.

He also cut his first recitations under the ‘Luke The Drifter’ guise. Hank’s songs seem to be echoes of the darkness of his life, in ways that other Country songs were not. The jaunty vaudeville presentation hid hard truths. He presented a brittle unyielding face to the world, but it was on ‘Luke’s often-morbid spoken poems – with a moral lesson, that he allowed his religious guilt to show. He was secretive, defensive, wary of betrayal, but the mask that Hank showed to the world was only allowed to slip in his songs, the lyrics, and their delivery.

‘Moanin’ The Blues’ – recorded in Nashville during 31 August sessions, became his fourth no.1 by October 1950 (b/w ‘Nobody’s Lonesome For Me’, MGM10832). ‘When my baby moved out and the Blues moved in’ had all of Hank’s trademark yodels sweetened by Don Helms steel guitar. It was followed by the classic heartbreaker ‘Cold, Cold Heart’ (b/w ‘Dear John’, MGM 10904) which became his fifth chart-topper by February 1951, with Chet Atkins adding stinging guitar. Hank was hurt and hurting, he was opening up his vulnerability in the song, her heart was shackled to a memory, yet there’s a poetic toughness in his hurt. This is music that transcends its time.

There may be questions about the song’s provenance, in that it creatively ‘borrows’ the tune from an earlier T Texas Tyler recording, but the delivery and interpretations is pure classic Hank Williams, grabbing the head and gut simultaneously. As litigation commenced, it was promptly covered by slick crooner Tony Bennett to become a Pop no.1 hit as well – conspicuously shorn of Hank’s emotional depth, while other artists were picking up on Hank’s songs, bluegrass star Bill Monroe (‘I’m Blue, I’m Lonesome’), Teresa Brewer (‘Honky Tonkin’’)… as well as Audrey’s own less-than-impressive Decca sessions! Whenever the right occasion arose Hank took the opportunity of pitching his songs to other artists. Sheet-music sales still represented a profitable market. Billboard magazine published a sheet-music chart alongside it’s record sales chart.

Hank next topped the country chart with ‘Hey Good Lookin’’ (b/w ‘My Heart Would Know’ MGM11000, 78rpm or 45rpm), which crossed over into the Pop charts when Frankie Laine recorded it as a duet with Jo Stafford. Where Hank is inching towards Rockabilly, with teen-slanted lyrics about hot rods and soda pop, Frankie Laine makes that even more explicit with an upbeat jumpy bassline. ‘Hey Good Lookin’, what you got cooking?’ had that mildly flirtatious way of working itself into everyday conversation, on the works shopfloor, in Bars, in the store, wherever people meet and interact. The song reached out across the Atlantic too, although it might have been through voices other than Hank’s. By getting BBC radio plays it insinuated its magic into Britain.

Meanwhile, slipping over the rim of the new decade there were changes shifting the music industry in novel directions, with the new 45rpm and twelve-inch LP albums making inroads into Record Store sales, although a jukebox hit – regardless of format, determined higher ticket prices for concerts. And Hank had the hits. While, to give a further sense of timescale, a rival version of Luke The Drifter’s ‘The Wayward Daughter’ was performed by a then-obscure Bill Haley and his then-group, the Saddlemen. In a rare interview for the San Francisco Chronicle Hank spoke to 35-year-old Ralph J Gleason, who later co-founded Rolling Stone music magazine. Gleason was both intrigued by Hank’s diet of pills for breakfast, but equally by his charismatic live performance and riveting conviction.

But constant touring was taking its toll on Hank’s health – as a headliner now, before there were such things as interstates and orbital freeways, he was driven in a sedan with the attendant sleep deprivation and drinking jags. He double-headed a tour with Lefty Frizzell. He played a Hadacol Medicine Show caravan on the same bill, not only as Opry-regular Minnie Pearl, but Bob Hope and Milton Berle. And Hank drank. It was his life-support system, and his demon. Carrying a dead weight of physical and emotional hurt, it was his escape route from the tensions and mutual infidelities of his failed marriage to Audrey, and his crash-pad when they divorced, against his wishes. As Bill Graham astutely observed, ‘it was a superb environment for writing bruised love songs; it was a lousy life’ (in Hot Press). Audrey divorced him in May 1948, although they remained together.

A drunken fall from an Ontario stage aggravated his already worsening back-pain, leading to him wearing an ill-fitting lumbosacral brace, and there was failed surgery. ‘Now that’s what happens when you get too big for your britches, I been down that road before’ he wrote in a ‘Luke The Drifter’ talking Blues. Oddly, a discarded demo from this time, of a drinking song called ‘There’s A Tear In My Beer’ was much later rescued and eerily recorded as a ‘duet’ with Hank Williams Jr, complete with a digitally-contrived video that boosted it to become a no.7 Country hit in 1989.

Hank went to New York to shoot a Perry Como TV Chesterfield Show. And – in November 1951, his first of the only two LPs issued during his lifetime, was a ten-inch Hank Williams Sings (MGM E107) made up of eight lightweight songs recorded between 1946 and 1949, gathering ‘Lost Highway’ composed by blind Texan honkytonk singer Leon Payne, and gospel standard ‘I Saw The Light’ alongside failed single ‘A Mansion On The Hill’, no.2 hit ‘Wedding Bells’, as well as ‘Wealth Won’t Save Your Soul’ which was salvaged from Sterling Records before Hank had even signed to MGM. There were Hank original songs ‘A House Without Love’ and ‘Six More Miles (To The Graveyard)’ plus Slim Sweet’s saccharine ‘I’ve Just Told Mama Goodbye’. The cover shows skinny Hank with his guitar straddling a huge cartoon Stetson. Although the Country market still orbited around jukebox singles, and the album initially failed to sell well, posthumous sales over subsequent years in various rejigged compilation formats have ensured its longevity.

In the meantime, Hank finally cut a usable version of ‘Honky Tonk Blues’, following various abandoned attempts since his original Sterling sessions in August 1947, (b/w ‘I’m Sorry For You, My Friend’, MGM K11160) which took him to no.2 on the Billboard Country chart. With his appearances becoming increasingly unpredictable and erratic, he failed disastrously in Las Vegas, just as Elvis Presley would fail in four year’s time. Hank played the Last Frontier Ramona Room with vaudeville trouper Willie Shaw, 16 May 1952. Elvis played the New Frontier Hotel & Casino supporting the Freddy Martin Orchestra, 23 April 1956. The Sin City of Lost Wages was not ready for either of them.

Yet the final six months of Hank’s life yielded a series of classics that would define what Country music could aspire to. Songs that reconfigured the vocabulary of Country music. He went Cajun patois – ‘pick guitar, fill fruit jar and be gay-o,’ and released ‘Jambalaya (On The Bayou)’ (c/w ‘Window Shopping’, MGM K11283, July 1952), which became his most covered song. Although it was based around earlier forms, and likely has a Moon Mullican input – the Hillbilly Piano Player issued his own very different version of the song the same month, it is undeniably the work of Hank Williams. The Drifting Cowboys on the Nashville Castle Studio session were Chet Atkins (lead guitar), Jerry Rivers (scratchy fiddle), Don Helms (sighing steel guitar), Chuck Wright (plonking bass) and likely Ernie Newton (bass). The single topped the Country chart for fourteen straight weeks, and went on to be interpreted by eleven-year-old wunderkind Brenda Lee, by Fats Domino, Swedish group the Spotnicks, Emmylou Harris, Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buck Owens John Fogerty’s Blue Ridge Rangers, Gerry & The Pacemakers, George Jones… the list goes on!

Hank recorded ‘I’ll Never Get Out Of This World Alive’ at the same session – a cowrite with Fred Rose, that would hit no.1 in January 1953, soon after his death (c/w ‘I Could Never Be Ashamed Of You’, MGM 11366). Although intended to be tongue-in-cheek about a man who ‘had lots of luck, but it’s all been bad,’ Hank’s death invested the lyric with ironic poignancy that took it to no.1 on the Country chart.

‘You Win Again’ was issued as the flip of what was considered to be the more up-tempo radio and jukebox-friendly ‘Settin’ The Woods On Fire’ (July 1952, MGM 11318). Recorded the day after his final separation from Audrey it’s not difficult to see where its mournful defeated vitriol is pointed. Pain is etched in every groove, for ‘trusting you was my great sin.’ A Pop version of the song was issued by MGM on the same day by smooth balladeer Tommy Edwards, who took it to no.13. When asked how he wrote all those sad songs, Hank replied, ‘Hell boy, you can’t just write ‘em, you gotta live ‘em.’

Taken from his final recording session (23 September 1952) both sides of ‘Kaw-Liga’ c/w ‘Your Cheatin’ Heart’ (January 1953, MGM K11416) show directions his writing may have evolved. With some tinkering and pointing from Fred Rose, ‘Kaw-Liga’ opens with drummer Ferris Coursey’s tribal rhythm, leading into the narrative about the storefront Indian’s unspoken love for the ‘Indian maid over in the antique store.’ It’s both a cute novelty song and a metaphor for masculine emotional inflexibility, a man who ‘stood there and never let it show.’ There’s a tempo-change into the chorus over scratchy fiddles, and – unique among Hank’s records, a fade ending. Issued posthumously it topped the charts for 14 weeks, while ‘Your Cheatin’ Heart’ was no.1 for six weeks in its own right.

‘Your Cheatin’ Heart’ – at a concise 2:41-minutes, may be another backwards snipe at Audrey, prickly with hurt, ripped from Hanks suffering soul, but it motivates one of the greatest Country songs of all time. To writer Greil Marcus, this is evidence of how Hank ‘went as deeply into one dimension of the Country world as anyone could, gave it beauty, gave it dignity’ (in his book Mystery Train). A sparse demo recording of the song, with just Hank’s guitar, sounds even more vulnerable and starkly bereft. Again, it has been multiply copied across the years since, with a jaunty Elvis Presley version, a gutsy piano-led Jerry Lee Lewis, a massively orchestrated yet movingly soulful Ray Charles on his 1962 Modern Sounds In Country & Western Music vol.2, while George Jones and Willie Nelson take it back into mainstream Nashville. Del Shannon does a heartfelt cover on his 1965 tribute album Del Shannon Sings Hank Williams (US, Amy 8004). Yet none can capture Hank’s naked desolation.

Freed from Audrey, Hank was in free-fall. Unable to deal with the situation, Ray Price quit the Drifting Cowboys. Without a regular band Hank used pick-up musicians, including piano-player Floyd Cramer. He was fired from the Grand Ole Opry due to his drop-down drunk unreliability, although he continued to play the Louisiana Hayride, until they granted him ‘leave of absence’ on ‘health’ grounds. Hank had a contested-paternity child with ex-girlfriend Bobbie Jett. He had a flirtation with Faron Young’s feisty former flame Billie Jean Jones. Their marriage, onstage in New Orleans, was later ruled invalid as she was already technically married! Which became a factor when they were fighting over the spoils of Hank’s legacy

A second ten-inch album – Moanin’ The Blues (MGM E168) was issued in September. The cover-art has a photo of Hank’s face superimposed over a cartoon body wielding a huge guitar. Again, it was made up of previously released material including three no.1s, ‘Lovesick Blues’, ‘Long Gone Lonesome Blues’ and ‘Honky Tonk Blues’, plus two more charting singles, ‘I’m A Long Gone Daddy’ and the title cut. The rest of the material were Hank original songs, ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry’, ‘The Blues Come Around’ (flip of ‘I’m A Long Gone Daddy’), and ‘My Sweet Love Ain’t Around’ – a failed January 1948 single. His next venture into long-playing territory, in full twelve-inch format, would be the posthumous Hank Williams’ Memorial Album MGM E202), a Greatest Hits repackaging of his more familiar songs.

When he played, he could still be mesmerizingly charismatic, but there were drunk-shows and no-shows, an unreliability that meant major venues were wary, so he was booked into small beer joints and honkytonks hardly worthy of his hit record status. Living with Billie Jean and her brothers in Shreveport followed the same pattern it had with Lilly or Audrey, complicated by bouts of heart-murmurs, impotence and incontinence brought on by his physical condition, and by years of abusive substance-dependency. By now, writes Colin Escott, ‘too many of his self-destructive behaviours were hardwired.’ Spina bifida is still not curable, although surgical techniques, medications and treatments have vastly improved since Hank’s time and location, to the extent that sufferers can now enjoy long and productive lives. Hank just suffered, bruised, buffeted and directionless.

There’s film of Elvis Presley’s final performances where he’s grossly overweight, unhealthily bloated and sweating profusely with effort, where his poor physical condition is so apparent you wonder why he was allowed to continue, why no-one on his entourage had the guts to say ‘stop’. But no-one did, they were all dependant on the King’s gravy-train, while Dr George Nichopoulos overprescribed him addictive drugs at will to ensure his continued inclusion in Presley’s lucrative inner circle. A journalist suggested that Creedence Clearwater Revival should kidnap Elvis to a remote log-cabin and just Rock ‘n’ Roll him back to health. Unfortunately, Creedence Clearwater Revival were otherwise engaged.

It was the same with Hank Williams. Based back in Lilly’s boarding-house in Montgomery, the touring schedule was killing him, but no-one had the compassion to say ‘stop’. If he could have quit doing gigs or reduced his workload in order to concentrate on songwriting, things might have worked out differently. But no-one did. He had bills to pay. He also had a quack doctor – Horace ‘Toby’ Marshall, writing him prescriptions for the dangerous drug chloral hydrate, taken in combination with barbiturates and alcohol. Perhaps, after his body had endured years of punishing wracking pain, Hank was simply tired of it all, and no longer cared?

Hank played what would be his final show to the American Federation of Musicians at the Montgomery Elite Café on Sunday, 28 December, then set out on a long cross-country drive to Canton, calling off at Oklahoma City for a show that was subsequently cancelled. Fortified with morphine shots, Hank was slumped in the back seat of his Cadillac convertible, driven by young Charles Carr. They stayed over at Knoxville. After driving a solid twenty hours they picked up a relief driver – Don Surface, at a Doughboy Lunch Restaurant in Bluefield, then drove on into West Virginia. When they pulled into the Oak Hill Burdett’s Pure Oil station for fuel and coffee at 6:30am 1 January 1953, they discovered Hank was dead. He’d quit the world, drifted away gradually, becoming detached from life as they drove. Rushed to Oak Hill Hospital emergency department he was declared dead at 7:00am. The hurried autopsy found alcohol and morphine with an assist of chloral hydrate in his system, but the official cause of death was ‘heart failure aggravated by acute alcoholism.’

As the family and wives fought over his legacy, the Grand Ole Opry reclaimed and celebrated the star-crossed idol, despite having fired Hank, and a song he’d recorded 23 September 1952 at his final Nashville session – ‘Take These Chains From My Heart’ c/w ‘Ramblin’ Man’ (MGM 11479) leapt to no.1 on the Country chart. It was a Fred Rose composition, but despite not being his own song, he sounds on the verge of tears as he sings, no-one but Hank could channel such raw emotion into his voice. Again, there were multiple covers, including a radically different but equally soulful string-drenched Ray Charles version, which became a huge 1962 hit on both sides of the Atlantic.

It was followed into the charts by ‘I Won’t Be Home No More’ c/w ‘My Love For You (Has Turned To Hate)’ (MGM 11533) in July, as a sales tidal wave of Hank Williams records reached highs he’d seldom enjoyed in life. As with Buddy Holly’s final apartment tapes, early Hank radio sessions were overdubbed with new instrumentation – initially by members of the Drifting Cowboys, as the archives were dredged to meet the demand for new Hank Williams product. A further single, issued in September 1953 – ‘Weary Blues From Waitin’’ c/w ‘I Can’t Escape From You’ (MGM 11574), was a Hank song that had begun as a 1951 demo, which was overdubbed for release, and hit no.7 on the Country chart. Far from ending, the stetsoned Alamaban’s legend had just begun. From a vinyl drip-feed to a CD deluge.

Among the innumerable versions of the Memorial Album (1953), to The Immortal Hank Williams (1956), were The Unforgettable Hank Williams (1959), The Spirit Of Hank Williams (1961), Greatest Hits (1961) and 42 Of His Greatest Hits (1962), The Very Best Of Hank Williams (1963), The Many Moods Of Hank Williams (1967), The Essential Hank Williams (1969), Memories Of Hank Williams Sr. (1973), to endless Best Of and Greatest Hits reshuffled into new editions.

The compilation The Legend Lives Anew (1966, MGM-C-8031) features old tracks doctored with new string arrangements and the Jordanaires vocal harmonies. Live At The Grand Ole Opry (1976, MGM 2353-128) is salvaged from tapes supposedly recorded 11 June 1949, but there is between-song dialogue with Minnie Pearl that suggests otherwise. The advent of CD unleashed a three-disc 83-track compilation The Original Singles Collection… Plus (1991, Polydor 847-1942) which gathers his MGM sides augmented by what Q magazine calls ‘an unlistenably low-fi music store acetate from 1942 and ends with unreleased home demos from the last days of his life,’ that is – from ‘I’m Not Coming Home Anymore’ digitally restored from Cedar Audio Ltd, to ‘Something Got A Hold Of Me’ which is a duet with Audrey, to the original demo of ‘There’s A Tear In My Beer’. To reviewer David Hepworth the best of Hank’s work is ‘so deeply embedded in the crust of popular music that it seems odd that anyone ever actually wrote them, let alone an alcoholic near-illiterate from poor Alabaman who never saw his thirtieth birthday.’

MGM records was part of MGM pictures. There were inevitable crossovers. Your Cheatin’ Heart was a flawed 1964 biopic filmed in black-&-white, but later colourised, with George Hamilton playing the doomed Hank, lip-synching to songs sung by Hank Williams Jrn. ‘The Immortal Hank Williams Lives Again, Sings Again’ shout the posters, but – directed by Gene Nelson and produced by Sam Katzman, it was made with Audrey’s approval (played by Susan Oliver), ensuring that it was heavily slanted. It was followed in 2015 by I Saw The Light, a more authentic telling of his story, which finds space for Billie Jean (played by Maddie Hasson) who had been airbrushed from the earlier movie at Audrey’s insistence (played here by Elizabeth Olsen).

To Colin Escott, the arc of Hank’s career occurred within a fortuitous window in which radio and TV carried his image and his music to a wider audience than was previously possible, but ended before the advent of Rock ‘n’ Roll which would have rendered his hillbilly style anachronistic. In truth, Hank’s problems were intractable, if he hadn’t faded away on the road to Canton it’s difficult to see how he would not have died elsewhere. But Country was a powerful input strand to Rock ‘n’ Roll. The other strand was R&B, and Hank had a clear affinity to the Blues that went all the way back to Rufus ‘Tee-Tot’ Payne on the streets of Montgomery. So, in a theoretical timeline in which he survived in tolerable health, it’s not inconceivable that Hank would see the rise of Rock ‘n’ Roll as a challenge that would have provoked him to greater creativity. It’s impossible to know, but it’s tempting to conjecture.

‘Are You Sure Hank Did It This Way?’ asked Waylon Jennings. Yes, this is exactly the way Hank did it. If not quite as extreme as ‘popular music’s first outlaw, the model for every live-fast, die-young rocker’ that Record Hunter magazine claimed him to be. Of James Dean’s ‘Live fast, die young, leave a good-looking corpse’ Hank Williams only managed to die young. But his legacy remains. To Gavin Martin, ‘alive, he was a living disgrace, an increasingly embarrassing affront to the goodly face and gentrification of those who were building Country music into a respectable big business. Dead, he was tamed, a tidied myth’ (Record Hunter, November 1990).

As Colin astutely points out, ‘most of Hank’s contemporaries lived long enough to make some very bad records. Hank didn’t.’ Hank’s great sales rival, Eddy Arnold, survived long enough to enjoy a maudlin UK no.8 hit with ‘Make The World Go Away’ as late as 1966, by which time Hank had become an iconic memory.

Book Review of:

‘I SAW THE LIGHT: THE STORY OF HANK WILLIAMS’

by COLIN ESCOTT with George Merritt & William MacEwen

(2015, Two Roads Publishing ISBN 978-1-473-63461-9)

www.tworoadsbooks.com

Movie adaptation starring Tom Hiddleston as Hank Williams

.