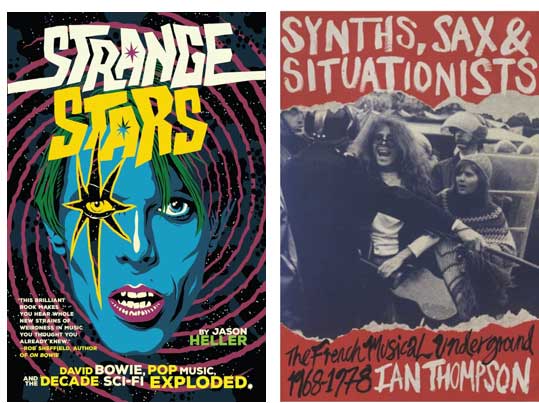

Strange Stars, Jason Heller (Melville House)

Synths, Sax & Situationists, Ian Thompson (Roundtable)

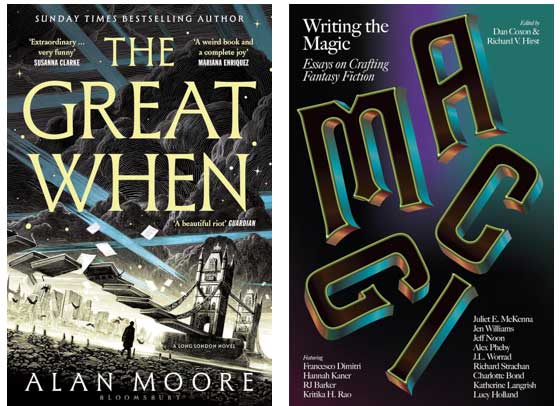

The Great When, Alan Moore (Bloomsbury)

Writing the Magic, eds. Dan Coxon & Richard V. Hirst (Dead Ink)

In Strange Stars, Jason Heller considers ‘David Bowie, Pop Music and the Decade Sci-Fi Exploded’. At least, that’s what the subtitle says. What it actually is is a rather longwinded trawl through 1970s music trying to document any music that seems to have science fiction content, sometimes even a title. Fantasy, however, is not allowed and is in fact rather looked down upon. No trolls or elves or magic potions here, only rockets, spaceships, deranged astronauts and UFOs. Lots of spaceships and UFOs.

The book blasts off with Heller’s own memories of a David Bowie gig he saw in 1987 but quickly time travels back to ‘Space Oddity’ and the Apollo missions at the end of the 1960s. Bowie will reappear throughout the book, sometimes through the use of generous authorial loopholes: ‘There may not have been concrete sci-fi themes to Bowie’s 1977 output but still sci-fi guided it’ being just one example.

In fact the whole book is peppered with sometimes unfathomable reasons for inclusion or exclusion, although there’s a core of music and bands that are necessary albeit obvious: Hawkwind, Gong, Kraftwerk (included it seems for sounding science fiction more than anything else) and other krautrockers, Ultravox! (Heller doesn’t seem to understand that the band only dropped the exclamation mark when John Foxx left and Ultravox became a crap pop band, so doesn’t include it), Sun Ra, Parliament & Funkadelic, and Gary Numan. [Wash your mouth out – Editor]

More interesting is when Heller does some digging and makes a case for inclusion with albums by the likes of Bill Nelson’s Red Noise, Paul Kantner’s Blows Against the Empire or bizarre choices such as X-Ray Spex’s wonderful (but not sci-fi at all) Germfree Adolescents. Mostly, however, it’s an obsessive list, pausing only for some filmic and bookish diversions with the likes of J.G. Ballard, Michael Moorcock, Star Wars and Dune. I kept expecting some sort of argument or thesis to emerge but it never did. It’s well-intentioned and a fun read but nothing more.

Unlike Ian Thompson’s Synths, Sax & Situationists which takes a deep dive into ‘The French Musical Underground 1968-1978’. In theory this overlaps with Heller’s book but apart from one or two occasional mentions of people like Richard Pinhas, it doesn’t. When Thompson says underground he means underground. This is deep tunnel in-the-dark obscurity.

Here are the early commune-dwelling pothead pixies of Gong, conjuring up their own psychedelic mythologies whilst stoned out of their brains. Here are Magma, inventing their own alien languages to weave progrock science-fiction epics of unlistenable strangeness. Here are the original Red Noise, that Bill Nelson presumably nicked the name for his post Be Bop Deluxe project from, Richard Pinhas’ King Crimson inspired band Heldon, and the very wonderful Etron Fou Leloublan with their quirky music and impossible humour. (I recommend 1977’s les trois fou’sperdégagnent au pays des…)

There was definitely something in the European mainland’s water at the time, which produced impossible mixes of jazz, improvisation, space rock and traditional folk music. Guitars and saxophones interrupt themselves and each other, looping and drifting whilst flutes and keyboards soar above or delve into the percussion and bass foundations. And it’s not just Gong who write strange lyrics either, although it has to be said I don’t speak French very well, let alone Magma’s Kobaïan. But if you like being introduced to neglected and obsucre music then Synths, Sax & Situationists is for you: you won’t be disappointed.

You won’t be disappointed either by Alan Moore’s The Great When, which is now out in paperback. Set in postwar London, its hapless hero (or anti-hero) Dennis Knuckleyard not only has to grapple with his ridiculous surname but also being orphaned and [un]cared for by the most foul-mouthed and brutal secondhand bookshop owner alive. She delights in giving Dennis as many things to do as possible to keep him out of sight and mind, as well as heckling and abusing her long-suffering customers.

She is a sweary, comic delight but there is dark magic afoot, which Moore is adept at conjuring up. This time it’s a portal between the real London and a shadowy doppelgänger city, the titular Great When. There the unreal becomes real and concepts become physically incarnated as mysterious and unfriendly forms. Dennis, of course, has to return the book that caused all this to shut the portal and this is the story of his quest. On the way he meets a number of fantastical characters and explores the sideways and byways of both the real and other London. It’s a gripping read and a model of genre subversion.

I was going to say ‘a model of genre subversion that many of the contributors to Writing the Magic, Essays on Crafting Fantasy Fiction would not like’ but that is to do a disservice to many of the contributors to this provocative anthology. Although there are far too many mentions of Tolkien for my liking, not to mention the usual crap about ‘Authenticity and Voice’, the book very quickly steps aside from any expected trajectory as RJ Barker, in the second essay here, suggests that ‘You Do Not Need to Know How to Write a Book’ and urges readers and would-be authors ‘to Embrace Ignorance and Run With It’.

In a similar manner Jen Williams tells us about ‘Building a World and Getting Away With It’, whilst in a section on myth and tradition Hannah Kaner explores ‘The Domestic and the Divine’ and Katherine Langrish reminds us – in the words of Joan Aiken – that ‘It is the author’s duty to demonstrate to children that the world is not a simple place’, and considers books by the likes of Alan Garner that does this whilst using the simple idea of ‘The Door in the Mound’.

Best of all are the ‘Spotlight on…’ sections featuring Michael Moorcock and Ursula K. Le Guin, even though the former concentrates on the Elric novels rather than Moorcock’s later, more experimental books. Jeff Noon’s take on ‘Creation Magic’ is great too, as it documents the genesis and beyond of a specific collaborative project. Although I sidestepped a chapter about ‘Fantasy and Tie-In Fiction’ and have a couple of very brief answers to Juliet E. Mckenna’s question ‘What Can Tolkien’s Creative Process Teach a Writer Today?’ (‘Nothing’ or ‘Get an editor’), in the main this is an intriguing, wide-ranging and at times provocative group of opinions, confessions, ideas and advice.

.

Rupert Loydell

.