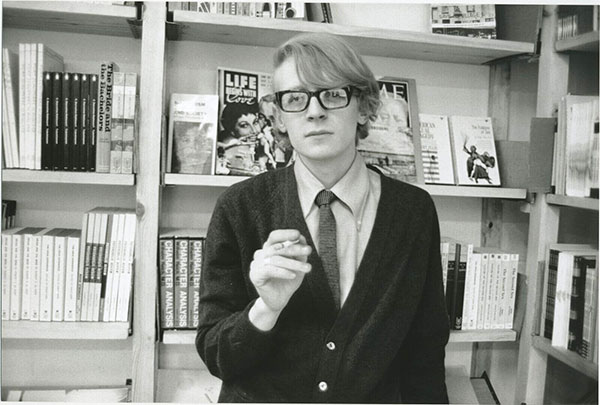

BACK IN JUNE, as the 60th anniversary of the International Poetry Incarnation at the Albert Hall was commemorated, we spoke to legendary Beat historian and biographer BARRY MILES, simply Miles to most, about the ins and outs, the ups and downs, of that remarkable occasion.

But that mid-1960s landmark event was, in many ways, just the beginning of a six-decade adventure that saw Miles found a countercultural newspaper, steer a spoken word record label, become a regular correspondent for the burgeoning British music press, maintain close friendships with Ginsberg and Burroughs and produce an extraordinary run of books on the underground, alternative politics and rock culture.

The author, who has multiple titles to his name – London Calling, In the Sixties, Call Me Burroughs, The Beat Hotel and Allen Ginsberg: A Biography to name only a few – returns to chat with regular R&BG contributor LEON HORTON about his lifelong bond with McCartney, International Times, his musical tastes from jazz to punk, his literary affections from the Beats to Blake, the failed experiment that was Zapple and his serious doubts about Kerouac.

___________________________________________________________________

Leon Horton: In our previous interview we discussed in depth the 1965 International Poetry Incarnation at the Royal Albert Hall, which you described as ‘the birth of the London underground’. Three months later you left your job at Better Books and, with John Dunbar and Peter Asher, set up Indica Gallery and Books. What did you want to do at Indica that you couldn’t do at Better Books?

Barry Miles: Tony Godwin, who owned Better Books, sold the shop to Hatchard’s of Piccadilly, a very old respectable shop – still is – and it seemed extremely unlikely that the poetry readings and avant garde film screenings would continue under their management as they were just looking for a presence on Charing Cross Road, then the premier bookselling street in Britain.

LH: When did you first become aware of the Beat writers? Which of them did you most relate to?

BM: In 1959 I took my art A-level GCE a year early and went to Gloucestershire College of Art in Cheltenham aged 16. There I met the other art students and one of them had a copy of ‘Bomb’, by Gregory Corso, tacked to the wall. Intrigued, I wrote off to the address on the broadside and, sometime later, received a postcard from City Lights with a printed list of about ten titles, plus a few extras hand typewritten, of their stock list.

I ordered two dollars from the post office which took a week to arrive and sent off for a selection of books. I still remember what they were. On the Road and The Dharma Bums, both 35 cents, Abomunist Manifesto and Second April by Bob Kaufman, Bomb by Gregory Corso, and Howl and Other Poems by Allen Ginsberg. Not bad for $2!

A parcel from the USA was a rare thing in those days. I loved them all. I was 16 and I’d never read anything remotely like this before. A bit later, I saved up and bought a copy of Ferlinghetti’s A Coney Island of the Mind. I suppose On the Road was initially the most influence on me because it is a perfect book for exploring the world.

Throughout my years at art college I hitch-hiked many weekends to Oxford and to London and eventually all over the south coast and several times to Edinburgh, though this was the usual method of transport for art students, not necessarily a ‘Beat’ thing. I pretty much memorised ‘Howl.’

LH: Who are your favourite music artists, what are your favourite albums?

BM: I grew up with doo-wop and early rock‘n’roll. For me rock was a Black thing: first the Drifters, the Platters, Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, the Coasters, the Penguins – dozens of them – then Fats Domino, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Bo Diddley, Ray Charles…

Then, as the original energy and excitement got watered down by the mostly white record industry and became much more commercial and boring, I turned my attention to jazz. Art students were particularly fond of trad, which was about the only jazz I could find live in Britain at the time.

On record I listened to Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, the Jazz Messengers, Miles Davis, etc. Throughout art school I only owned one album, Ray Charles Live, with a wonderful extended version of ‘What’d I Say’ on it.

LH: Is your taste in music related to the Beats in any way? Were you drawn to bands and artists – Dylan, Bowie, Patti Smith, etc – who acknowledged a debt to them?

BM: None of the Beats were very musical. Burroughs was tone-deaf and didn’t even own a record player. Allen was more interested in Dylan and company as people than for their music. I first met Bowie when he was a mime artist at the Arts Lab and we did discuss the Beats, but none of those people influenced me.

I knew Patti Smith when she and Robert Mapplethorpe came to live at the Hotel Chelsea where I was also living. She was a poet then, and I still like her poetry and writing. I have always disliked her music except the first album which, to me, is a John Cale album [Note: Cale produced the record, Ed.].

My musical taste was certainly influenced by Peter Asher of Peter and Gordon, who explained many, many things about record production and what was good and what was bad. He and I, and John Dunbar, started Indica Books and Gallery together.

I was probably most influenced by Paul McCartney, who lived together with Peter and Jane Asher in the Asher household on Wimpole Street, a short walk from my place. Paul gave me records and introduced me to the work of [bassist] James Jamerson whom he particularly admired.

The Beatles all had the American Billboard Top 100 sent over each week, so he often had accidental duplicates. I remember how he deconstructed Fontella Bass’s ‘Rescue Me’, explaining how it was put together, and what was good about it, before giving me the record. The bass line by Louis Satterfield is incredible.

From 1966 onward I began attending Beatles recording sessions and so became very influenced by the opinions of the other Beatles, by George Martin and the recording engineers I met there. I know this all sounds like name-dropping, but you did ask!

LH: In 1966, you were involved with founding the alternative newspaper International Times. How did IT see itself in relation to the music scene and mainstream journalism?

BM: IT was an alternative press title so, by definition, we had nothing to do with the straight Fleet Street press of the time. Back then you had to have two years’ apprenticeship on a provincial paper before you could work in Fleet Street, so by the time they got there most Fleet Street journos were thoroughly indoctrinated in English middle-class hypocritical values and devoted to maintaining the status quo.

There was no contact and, as far as I know, no-one on IT ever moved on into Fleet Street. Later papers like Oz and Friends did provide new blood for Fleet Street. Mostly IT people went on to the music press. Mickey Farren, who used to edit IT in the 70s, joined NME, Nick Kent came from Friends, Pennie Smith, Chalkie Davies, Caroline Coon on Melody Maker and many others came from the underground scene.

At IT we carried the kind of news and articles that the Fleet Street papers knew nothing about. We had no connection with the music business until one day I was complaining about lack of money to Paul McCartney who said, ‘You should interview me, then you’ll get record company advertising.’

That shows how out of it we were. I hadn’t thought of anything as obvious as that. So I went over to his place and taped an interview, and, sure enough, EMI started to buy ad space. Then Paul said, ‘You should interview my friend George.’ So I invited George and Patti over for dinner and taped my second ever interview. Almost entirely about Hinduism as I remember.

Then Mick Jagger asked if he could be interviewed, so he came over to my place and we did a great interview about politics – it was the time of ‘Street Fighting Man’. And my fourth interview was Pete Townshend, who was a regular at the UFO Club and whose wife Karen used to make the shirts that we all wore.

In some ways it was downhill after that. I interviewed John Lennon and Frank Zappa, and Pete very kindly gave me a very long exclusive interview on [the rock opera] Tommy, going over it track by track, which we ran over two issues of IT, but I was unable to keep up the stellar names.

Foolishly, it never occurred to me to interview Syd Barrett or the Floyd, even though they were the house band at the UFO Club where the IT staff all worked each weekend to ensure that they at least made some money, our finances being very uncertain.

I did Graham Nash and maybe a one or two other musos but then didn’t write about music again, except for a few articles in Rolling Stone and Crawdaddy, for six or seven years.

LH: You have worked in mainstream music journalism yourself, most notably for the NME [New Musical Express] in the 1970s. What were your feelings about punk music at the time?

BM: In October 1976 I was asked by Neil Spencer, features editor at NME, to review a punk gig by the Clash at the ICA. He was sceptical about them as they had a song called ‘White Riot’ that he suspected might be racist.

I liked the youthful energy though it seemed to me that there wasn’t much difference between them and the bands of a decade earlier except the length of their hair. I wrote somewhere calling them ‘hippies with short hair’, but of course they were all very anti-hippie, although in interviews years later most of them turned out to be Beatles or Stones fans.

Mick Jones was a Mott the Hoople fan and there are photographs of him with longer hair than most hippies. During the Clash gig, ‘Mad Jane’ Crockford [later a member of the Mo-dettes] appeared to bite Shane MacGowan’s ear off. There was a lot of blood.

It turned out she had actually cut him with a broken bottle. He later became frontman with the Pogues. Patti Smith clambered up on stage to dance to the band but was overshadowed by the so-called ‘cannibalism’ act that made the tabloid press.

There was no real philosophy behind punk, not that there was much more behind the hippies, and it was much more centred on music and clothes, less on vague ideas about revolution, love and mysticism.

The trouble was, once in the studio, the fact that most of the bands couldn’t play, or even properly tune their instruments, was a big problem. But there were some real talents there: the Damned were good, Mick Jones was a great player, I loved the Slits.

LH: Your friendship with the Beatles – most especially Paul McCartney – has been well documented, but how would you describe it?

BM: Accidental. As I said, I was into jazz when I first met Paul at Peter Asher’s household and the next day I went down to Imhoff’s record store to look at the Beatles albums because I didn’t know which instrument he played!

Jazz albums always had good sleeve notes that listed the instrumentation but as far as I remember Beatles records didn’t. Of course I soon found out by seeing them play at Abbey Road. They were recording Rubber Soul at the time I think.

LH: Is it true that you introduced McCartney to hash brownies?

BM: My wife, Sue Miles, was a cook and told Paul that she had just made some hash brownies using the recipe that Brion Gysin gave to Alice Toklas for her famous cookbook.

The next day, late in 1965, I came home from Better Books, where I was the manager, bringing Stuart Montgomery, the publisher of Fulcrum Press poetry books with me. There in the kitchen, perched on the draining board, was Paul, trying out the brownies with Sue. I don’t think she was ever less pleased to see me as at that time. Entirely Sue’s doing!

LH: You were heavily involved with Apple’s short-lived Zapple Records, of course, intended as an outlet for spoken word records. More than 50 years on, how do you feel about that venture?

BM: I was the label manager, appointed by Paul but with the encouragement of John and Yoko. It’s a long story that I’ve told at great length in my book The Zapple Diaries and more moderately in In the Sixties.

It was a great idea and I very much enjoyed producing albums with Charles Olson, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Charles Bukowski and Richard Brautigan. They were all later released on other labels.

It all grew out of an experimental recording studio that Paul set up in a flat that Ringo wasn’t using in Montagu Square back in 1966 that was mostly used by William Burroughs to record cut-up tapes and the soundtrack for Bill and Tony [Note: Tony was Antony Balch, Ed.] Bill’s boyfriend Ian Sommerville was the live-in recording engineer.

When Allen Klein took over Apple, Zapple was one of the first things to go.

LH: You also produced Allen Ginsberg’s Songs of Innocence and Experience LP, recorded in 1969. What do you think of the various Beat recordings you made over the years?

BM: Well the Allen Ginsberg Blake album was the most fun to do because it was a musical album and naturally took much longer, involved working with some great players – Elvin Jones, Don Cherry, meetings with people like Charles Mingus and the wonderful arranger Bob Dorough.

Also it was in New York City at a particularly interesting time in its cultural history: one evening Allen received a call at the studio and after we’d finished that day’s work we went down to Christopher Street to see the riot at the Stonewall bar. He calmed things down and spent time signing autographs for cops.

The album itself, though very amateurish sounding, does, I believe, capture the feel of what it must have been like to hear William Blake sing his Songs of Innocence and of Experience in taverns and at friends’ houses. Completely unlike the classical settings that had previously been made by such as Benjamin Britten.

We recorded more songs a year or so later in California, which were better because Allen had performed the songs live on stage for several years with [guitarist] Steven Taylor who had helped him improve his singing and microphone technique.

LH: Of the many biographies and histories you’ve written, which proved the most difficult and why was that?

BM: Technically the Zappa book because I couldn’t get clearance to quote his lyrics, which made life difficult. Had Frank still been alive it would have been easier as he was a friend and I used to stay with him when I was in Los Angeles and always saw him when he was in New York or London if I was there.

London Calling was quite difficult because there was so much material and the book got longer and longer until my editor insisted I cut it off before we reached the present day.

The Paul McCartney book was difficult only in that there were few or no written sources to draw upon, whereas with Ginsberg I had thousands of letters and hundreds of journals to use. I had Paul’s archives delivered to my home four boxes at a time but I doubt I found more than couple of pages of material there.

The book, Many Years from Now, was based on about 47 interviews with him, also conversations with people like Donovan and Marianne Faithfull plus my own memory. The book stops when the Beatles break-up so I didn’t have to deal with Wings and the solo years.

The logistics of meeting up were quite complicated at times but there were also perks like private jets and limos.

LH: London Calling, your history of UK Counterculture, is one of my favourite books. Of all your works, which are your favourite? Which do you think were most successful?

BM: London Calling was fun to write because I was writing about a subject I knew well and I knew many of the characters personally. Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now enabled me to re-visit my own past. I hadn’t seen Paul for 20 years and some of the interview sessions were just two old guys sitting wondering ‘What was the name of that chick?’

The Ginsberg and the second Burroughs book are the only ones I go back to look things up in but I haven’t re-read any of them since they were published. Onward and upward!

LH: You’ve written two biographies of Burroughs, compiled his bibliography, and worked on dozens of related projects, but I have trouble picturing the two of you together. I have no problem imagining your friendship with Victor Bockris –Englishmen abroad, as it were – but how would you describe your relationship with Bill?

BM: I first met Bill in 1965 after corresponding with him since 1964. We discussed the efficacy of magnetised iron in orgone accumulators – as you do! Bill was no good at small talk and shy and ill at ease with the public but in private he was a lot of fun and could be incredibly funny, particularly when he improvised routines.

I spent much of 1972 cataloguing his archives and every night, after work, we would have a drink then go out to dinner. Usually, it was just the two of us, sometimes joined by Antony Balch the filmmaker who lived in the building, or later by Brion Gysin who came over from Paris for the final stage of the cataloguing.

There were many sides to Bill and I particularly enjoyed it when he channelled his own self from the 40s. For example, we were once eating at the Kowloon in Soho when he jabbed me sharply in the ribs – we were sitting next to each other on a banquette – and said, ‘Dig that broad. She’s really stacked!’ It was like a time-trip back to an earlier decade. People forget that he and Joan enjoyed a vigorous sex life.

Or when a mutual friend of ours joined us wearing a transparent Indian cotton shirt: Bill hated to attract attention – el hombre invisible – and whispered to me as we set out for the restaurant, ‘Walk next to me so he has to walk behind, then no-one will know he’s with us.’

There were a huge number of subjects that we talked about: language, calendar systems, natural history (he knew far more than I), gossip about mutual friends, different projects, and so on. It was just a friendship based on mutual respect and interests.

It’s true it was a different friendship than that with Victor Bockris, who I first met in 1977, introduced by Allen Ginsberg. That was more active and involved a lot of socialising and clubs. He’s an old friend. In fact, Victor is coming to stay in three weeks’ time.

LH: Why did you choose to write 1998’s King of the Beats? Given the numerous biographies on Kerouac already out there, what was it that you wanted to bring to that table?

BM: I think that was [literary agent] Andrew Wylie’s suggestion. After doing both Ginsberg and Burroughs it seemed only logical to complete the trilogy, and in fact the three books were issued in a uniform edition several times by Virgin.

My role has always been as a promoter, a proselytiser, and advocate. Choosing which books to sell in your bookshop, recording spoken word albums, writing about, reviewing and publishing people I like and admire, cataloguing their archives, promoting the people I like as much as possible, writing their biographies all seems natural to me. That’s essentially what I do.

With Kerouac it was a bit of a failure. He was the first and only person I wrote a book on who I didn’t know personally. I’d very much enjoyed his work when I was young, and I thought he would fit the bill. But, of course, when I investigated his life and ideas, I found that he was and had always been a right-wing Republican.

He was in favour of the Vietnam war; his abandonment and treatment of his daughter was despicable; his antisemitism and later racism appalled me. I came to realise why Burroughs cut off all contact with him in 1958, and, though I tried to be objective and let the reader make up their mind about the man, I’m afraid my dislike of him came across all too well.

I still think books like Visions of Cody are great, but he is a very uneven writer, and I suppose I do regret having written that one. If he were alive now, he would be wearing a MAGA hat.

LH: Speaking of MAGA, we are living through dangerous days at the moment, with a global lurch to the right and an omnipresent threat of ‘cancellation’ felt by many writers. How do you feel about that?

BM: I feel very depressed about it. What can I say? I could rant on here for pages, but what’s the point? I don’t think I can do much about it at my age. I just hope they don’t burn all the libraries and museums down.

LH: Are the Beats still relevant?

BM: Depends on which Beat we are talking about! Many of their attitudes, particularly towards women, are irrelevant, obnoxious – in fact, sometimes quite Neanderthal. However, notions of taking responsibility for your own life, questioning all received ideas, loving your fellow man and woman, being anti-war, a belief that art and culture improve the world, etc. all seem even more relevant now than they ever were.

LH: Is the counterculture dead? What do you think it achieved?

BM: Of course here definitions are all important. I think in its wider sense, the counterculture of the sixties contributed enormously toward a more tolerant attitude in society: it contributed towards the breakdown in racism, particularly in Britain – in the US there was already a massive movement.

It informed and contributed to the women’s movement – many activists came from an underground press background. It helped end censorship in publishing and journalism. Think of the trials of Last Exit to Brooklyn, Tropic of Cancer, The Naked Lunch, Fanny Hill etc., the Oz school kids’ issue, etc.

It contributed greatly to legalisation of homosexuality and greater sexual tolerance; it narrowed the supposed differences between the sexes – if you walk around in yellow crushed velvet loon pants with a frilly shirt and long hair you are making a statement. Bowie wore a dress on an early album sleeve.

Well, this is a big subject, but I think the so-called ‘sexual revolution’ of the 60s was largely driven by the counterculture. By the end of that decade, it was finally accepted that women have a sex-drive, that men can have long-hair and still be heterosexual, and it is not necessary to be married in order to live together in a loving relationship. All of that was new information.

LH: I have asked this question of many writers: if there is one thing people consistently get wrong about you, something you would like to set straight, what would that be?

BM: It is very flattering that you should think that anyone thinks about me enough to get me wrong. For years Lawrence Ferlinghetti, for some reason, thought I was from a rich, aristocratic family. In fact, my father was a London bus driver and my mother a maid in a moated castle. I think people have written things that were wrong, but I’ve forgotten what they were.

LH: You’ve given us two superb memoirs with In the Sixties (2002) and the punkier In the Seventies (2011). Is there more to come? Can we expect In the Eighties, etc?

BM: Yes, I’ve finished In the Eighties which extends beyond the decade to complete my account of my friendships with Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs, as well as covering the many years of working on Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now.

It will be published by Trolley Books, an art and photography publisher distributed byThames and Hudson, and will be heavily illustrated – like the revised, illustrated edition of In the Sixties.

See also: ‘Interview #38: Miles, Part One’, June 11th, 2025

Editor’s note: Leon Horton is a UK-based countercultural writer, interviewer, and editor. He isthe editor of the acclaimed essay/memoir collection, Gregory Corso: Ten Times a Poet (Roadside Press, 2024), and interviewer of author Victor Bockris for The Burroughs-Warhol Connection (Beatdom Books, 2024). More recently he conducted an interview with Stewart Meyer for his Burroughs memoir The Bunker Diaries (Beatdom Books, 2025), a book just reviewed by Rock and the Beat Generation. A regular contributor to Beatdom, R&BG and International Times, his essays, feature articles and interviews have also been published by Beat Scene and Erotic Review.

The Olson recordings are particularly interesting (to me) … I’ve struggled with his poems, certainly the later Maximus pieces, but whenever I’ve heard recordings of them they’ve been much clearer …. Olson was a fabulous reader

Great interview/article … dead interesting

Comment by Steven Taylor on 20 November, 2025 at 10:48 am