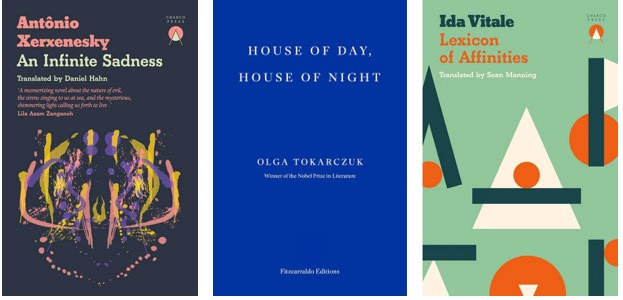

An Infinite Sadness, Antônio Xerxenesky (Charco Press)

House of Day, House of Night, Olga Tokarczuk (Fitzcarraldo Editions)

Lexicon of Affinities, Ida Vitale (Charco Press)

An Infinite Sadness is about melancholy, about rational science in opposition to nature, and about coming to terms with the past – in this case WW2. It is about a married couple: Nicholas, who works with the shell-shocked and mentally unwell; Anna, who commutes to a science institute.

Nicholas appears to be the haunted one, unable to find meaning, lost – metaphorically and in some ways physically – in the pain and problems of others and in the landscape around the couple’s house, yet Anna is just as lost in the complexities of the cosmos there seems to be no reason for and which she struggles to comprehend.

The book contrasts these two stories with those of Nicholas’ patients, with the couple’s own dialogues, which often seem at cross purposes. Nicholas comes close to despair, conversations and concepts remain unresolved, unresolvable, yet gradually the book lightens in mood, and there is a kind of calm resolution: wine, moonlight, a crackling fire. Life goes on: the moment must be enough, an acceptance of mystery and confusion must suffice.

Xerxensky’s book is set in Switzerland, Tokarczuk’s new novel in Poland, the West of Poland which was taken from the Germans post WW2. Poles were taken to this land and given houses to occupy and land to farm. It is initially all alien to the characters in House of Day, House of Night, but has gradually become home to a small community.

The residents’ back stories, religious beliefs, everyday lives and contemporary events are told in short episodes by a nameless narrator. She seems very real, yet also able to look inside people and to inhabit both the past and future. Later in the book she note how she sees and has always seen things differently, is always ‘ searching for constancy’, finally coming to the conclusion that

the only thing I can be sure of is that I’m flowing through a point

in space and time and I am nothing more than the sum of that

place and that time.

She goes on to add that

The one advantage to emerge from this is that the world seen from

a different viewpoint is a different world, so I can live in as many

worlds as I am able to see.

It remains unclear if our narrator is the very prescient human inhabitant of the village she first appears to be, some kind of supernatural being or perhaps simply a self-aware, omniscient narrator. Whichever she is, we gradually get to know Marta, the very old lady who lives next door; Paschalis, an abused monk, who goes on to transition into a nun and to write the story of Kummernis who should be made a saint; and the local school teacher, who is nicknamed Ergo Sum. There are many others too, from the past and present, as well as chapters focussed on mushrooms, recipes, rhubarb, specific events and festivals, and the strange ‘Cutlers’ who make knives and practice a strange non-deist religion of abandonment and despair.

The book’s back cover blurb calls it a ‘constellation novel’ but it is a more focussed, small-scale book than that. It has swept away the longwinded religious obsessions of Tokarczuk’s unwieldy and overlong The Book of Jacob, and learnt to create the eerie and disturbing rather than awkwardly describe it as she did in The Emposium, returning instead to the marvellous wit and play and humane domestic and personal detail of earlier books.

Lexicon of Affinities is, I guess, also a constellation work, but it might better be described as a network of stories, or a book of events, people and characters in orbit around the author. It is a marvelous kind of autobiography, told by looking outwards rather than inside, which allows the reader to make connections between the many entries in this alphabetically ordered collection.

It may tell us specifics about what the author sees, moments in her life, her friendships and offer up a personal history of the 20th century but mostly it is about creativity, inspiration and telling stories. As the final entry, zuibitsu, says, it is about ‘The asymmetry, the freedom, the independence of a text in relation to others’ and ‘the prodigious creative joy of those who came before from so many places to invent almost everything for us, even literary genres’.

All three of these books are re-inventing storytelling in their own way, each offers space and intrigue for the reader to feel involved in the construction and understanding of what they offer rather than simply be a recipient of a given narrative. I recommend them all.

.

Rupert Loydell