“Those are very nice boots you are wearing, my dear,” he said. “Where did you get them?”

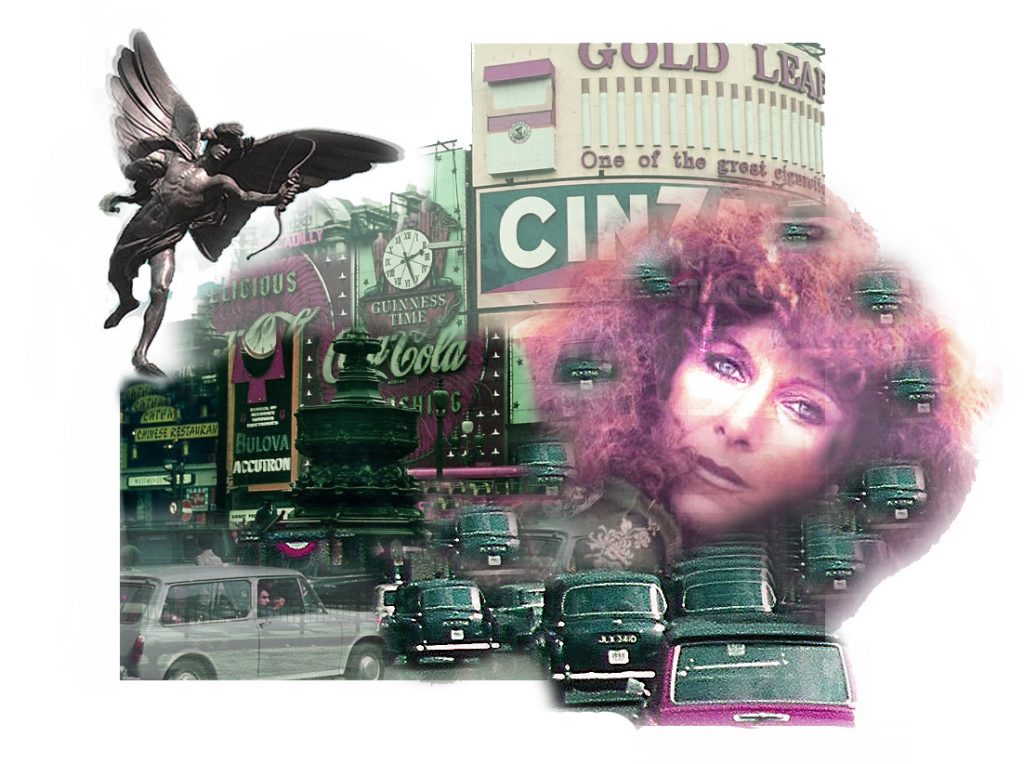

Waiting at Piccadilly for a taxi on a chilly November afternoon, I was approached by a tall, middle-aged gentleman sporting a black homburg. He had the customary brolly draped over his arm. He could have been a colonel or a banker with a home in Mayfair and a cottage in the Green Belt, the gin and tonic and bridge type.

Equally elegant in a Harris Tweed outfit, his handsome wife stood a few yards away.

“In Soho,” I answered, thinking naively that he wanted the information for his wife.

When he continued with, “You’re so pretty. What do you do, darling?” I realised he wasn’t only interested in my soft, black leather, knee-length boots.

“I’m a dancer,” I lied, deciding to amuse myself until the never-coming-taxi arrived.

“How interesting, and where do you perform, dear?”

“Oh, here and there. In Soho clubs, you know.”

“And what are you doing now? Maybe you’d join my wife and me for a cup of tea at our house?”

His daring invitation was appealing to my sexual fantasies, but good sense prevailed. What exactly would be expected of me? Would they take it too far? How far is too far? And what if they kill me and bury me all chopped up? My imagination jumped from Eros to Thanatos in a split second.

“I have to go home I’m afraid. My husband is waiting. He would be worried.”

“What a shame,” the gentleman said as he made to join his companion.

Just as I was beginning to curse the lack of London cabs, a taxi’s yellow light shone through the damp air which was turning my chestnut hair — that I’d had straightened at considerable expense just a few hours ago — back to its Medusa frizz

I gave a sigh of relief as I waved to the driver. At that same moment, a well-set determined man in Savile Row attire dashed, like a pigeon chased by a cat, from under the arcade in front of the Ritz Hotel. He put out his cane and stopped the cab.

I ran up to him. “I’m sorry!” I was adamant even though I immediately recognized him. “That’s my taxi, I’ve been waiting for it for a long time.”

Randolph Churchill, the bulldog’s son, Winston’s boy, looked at me and retorted with the assurance of his rank: “But I got it, so it’s mine.”

Before the word bastard had time to cross my lips, he continued: “Let me offer you a lift to your home.”

Our ride was a chatty one. He was forthcoming, inquisitive, interested.

“You’re not English? Ah, Yugoslav. I love Yugoslavia. I was parachuted there during the Second World War.”

This was a historic fact which I knew. “My father was a partisan then also,” I told him.

It was a pleasant journey which I was sorry to see coming to its end.

“Left at the lights, driver please,” I instructed.

“Is this it?”

“A few doors down.”

“Nice to have met you,” Randolph said, leaning forward and across me to open the heavy black door. Did I feel his arm press on my breasts?

“Thank you for the ride.” I gave him my best smile. (A smile which Francis Bacon had recently told me, at the Colony Room in Soho, that he would never be able to paint to perfection.)

At home I found Christine Keeler waiting for me. Yes, that Christine, the charismatic young woman who had been the protagonist of the ‘Profumo Affair’. That rough diamond, who had emerged from the gutter to take London by storm and had been destined to make history.

We’d met her shortly after she came out of prison. John Rudd, an old friend of ours from Johannesburg, whose grandfather had been a partner of Cecil Rhodes, the Rhodesian diamond magnate, brought her round to our place and we became friends immediately.

Although she was always much more Hugh’s pal than mine I enjoyed her free spirit and gutsy anarchy and for some years there was a sisterly feeling between us.

“Nice to see you, Chris,” I said as I threw my handbag and black velvet jacket on a wooden chair.

“Hugh let me in,” she said lifting her brown, doe eyes from the mug of steaming tea she was sipping. “I hope you don’t mind, I made myself some tea.”

Putting it down on the low, pine table in front of the settee, she picked up her cigarette from a butt-heaped ashtray. “He’s gone to the Queen’s Elm and says to join him there.”

“I just got a taxi ride with Randolph Churchill!” I was chuffed. After all it’s not every day one gets a chance to have a tête-à-tête with the son of one of the world’s most famous men.

She blew out a mouthful of cigarette smoke. “Did you ask him up?”

“No! Of course not.”

“You should have,” she said, brushing off a bit of ash that had fallen on her navy blue skirt (which was even shorter than mine). Uncrossing her shapely legs and crossing them the other way she continued. “You know how the likes of him love the likes of us.”

This came as a surprise. I’d never thought of myself as the likes of us.

The likes of whom, then? I asked myself.

Well, here’s a story:

Two frogs fell into a bucket of cream. The first frog said, “We are done for,” and drowned. The second frog began to swim furiously. Round and round she paddled for dear life until the cream churned to butter and she was able to stand on it and jump out.

I consider myself the likes of that second frog.

Hanja Kochansky

Illustration: Claire Palmer

Review by Heathcote Williams:

“She can light your darkest hour” Fran Landesman wrote in a song about Hanja Kochansky, the Croatian writer from Zagreb who cast her spell upon an already magical era: an elfin beauty with a crinkled Medusa frizz of flaming hair, piercing blue eyes framed by kohl and a smile so potent that Francis Bacon wilted at the thought of trying to paint it.

Light as a butterfly, she shows in this litany of love that it’s possible to live on air, to be a luftmensch.

It’s a winning tale. She travels with the subversive Christine Keeler, who brought down a government, to a hideout on the continent, comically revealing Keeler’s dread of foreign food as she stocks up in advance with cans of baked beans and Irish stew before catching the ferry.

Hanja’s antennae are finely tuned: she catches seminal events and records them. She’s in Rome for the Dolce Vita explosion, and becomes part of Cinecitta’s ‘Hollywood on the Tiber’ when she plays one of Elizabeth Taylor’s handmaidens in the film Cleopatra. She’s a pregnant Playboy Bunny; an avatar of the sexual revolution ushering in the Age of Aquarius; she’s in Amsterdam for the Wet Dream Film Festival; she’s a joyful feminist who knows how to follow the music’s beat while knocking on heaven’s door; her conscience has her recording the worst aspects of apartheid; her witty powers of observation has her recording the badinage of louche, Rabelaisian and picaresque drunks in the Queen’s Elm (“Get her tight enough and she’ll fuck anything, including the hairs on the barber-shop floor,”); her concern for human rights has her embracing Judith Malina and Julian Beck’s Living Theatre; her concern for an end to rigid linear thinking has her engaging with alternative psychiatry and Timothy Leary; she believes passionately in Illich’s DeSchooling Society and she educates her child accordingly.

She’s capable of thinking “beyond the beyond” like a Passionaria of the alternative: she was at the first Glastonbury: earth angel in the Vale of Avalon, and in that spiritual valley, the place of Blessed Souls, she wove her benign spells.

Sometimes the universe conspires to convey good news. It has done so in the form of Hanja Kochansky.

Heathcote Williams