The Complete Obscure Records Collection, Various Artists (10CD, Dialago)

Like John Cage before him, Brian Eno is not only a composer and musician – one who moved from electronic art rock to ambient to ‘space jazz’ to systems music to who knows where – but a visual artist, commentator, theorist and provocateur. Maintaining to this day that he is a non-musician, intent on speaking out on political/Political and social issues, and devoted to making music as the product of processes and concepts, he is by turns brilliant, annoying, perceptive and occasionally naive; but always consistent in his attention to detail, his consideration of sound (even if, as he suggested, ambient music was or should be as ignorable as listenable) and to collaboration, whether as sidekick, session musician, producer or record label.

Yes, you read that right. One of the most critically and publically ignored activities Eno has been involved in has been his two record labels: Opal and the earlier Obscure Records were both harbingers of new music, with the Obscure catalogue releases from 1975-1978 being particularly surprising and original yet including musical works, composers and musicians, that are now well-known in experimental, classical and art-rock music circles.

Despite only cult success and okay sales, Eno’s solo records were highly regarded critically and Island Records were gently persuaded that Eno’s proposal for Obscure was a viable proposition financially and culturally. Since his art school days Eno had been interested and engaged in listening to experimental music, and in addition to being a member of both the Portsmouth Sinfonia and Cornelius Cardew’s Scratch Orchestra, had links with many of the musicians who were part of London’s improvising and avant-garde music scene, many of whom would have albums released by Obscure. Michael Nyman, known mostly back then as a writer about music (his Experimental Music remains an important book) and composer/musician Gavin Bryars were fellow curators and advisers with Eno, which perhaps helped reassure and convince Island.

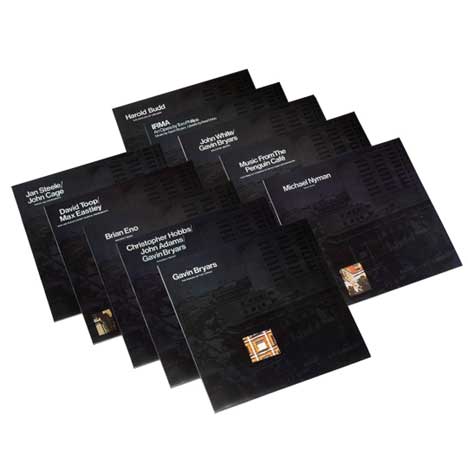

The albums were issued in covers that each revealed a different small part of the same cityscape photo; that is the image was obscured by black ink. Four were issued in 1975, three in ’76 and a further three in ’78. Original editions (some were repressed; some have been reissued, repackaged or put out on CD) remain elusive and collectible, although back in the day they could be found (and were by me) in the 10p bargain basement of Record & Tape Exchange in Notting Hill and other secondhand record shops.

The first Obscure album was Gavin Bryars’ The Sinking of the Titanic, which contained the title piece on side one and ‘Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet’ on the flip. Bryars had been involved in improvised music, film soundtracks and new composition; he was someone who used research and source material to inform his work. In this case the score, described as ‘fairly open indeterminate’ by Bradford Bailey in the fantastically informative booklet which forms part of this set, is underpinned by the idea of the ship’s band going down with their ship (and, presumably, their captain) and use of the American hymn ‘Autumn’ which was being played at the time, as well as ragtime and other music in the repertoire. Bryars’ underlying concept or conceit was that the band carried on playing under the sea until the boat was lifted from the bottom of the sea 63 years later; in addition to the orchestral music, there are prepared tapes, spoken word and a music box as part of the piece.

A tape was and is central to the better known ‘Jesus’ Blood…’, where a looped fragment of a tramp’s emotional hymn singing slowly sees the addition and layering of slow, stately instruments until everyone is playing; the music then slowly fades away. It remains an incredibly moving work, although for some reason Bryars later re-imagined and lengthened the piece, recording it with the very marvellous but in this case totally inappropriate Tom Waits. This first recording remains the definitive version.

Ensemble Pieces was attributed to Christopher Hobbs, John Adams and Gavin Bryars, who are actually the composers of the work presented here, although Hobbs and Adams also play on three of the four tracks. These three are playful systems pieces, featuring toy pianos and percussion (‘Aran’); reed organs informed by bagpipes; and one where musicians each keep pace with different cassette recordings only they can hear. This second album is probably more notable for the first appearance of recorded work by American John Adams, in this case a live piece recorded in San Francisco in 1973. The piece calls for ‘proposal, debate and vote’ to facilitate the organisation of the piece for available instruments, and predates the driving minimalism Adams would later become known for.

The first cluster of Obscure releases was completed by Brian Eno’s Discreet Music and David Toop and Max Eastley’s New and Rediscovered Instruments. Eno’s titular first side contains a long tape systems piece situated somewhere between the quieter work which had been released by Fripp & Eno and the ambient music which was to follow, whilst the second side is a slightly dull and academic reinterpretation of what Eno’s sleeve notes call part of ‘a very systematic Renaissance canon.’ In a similar manner, the Eastley tracks on New and Rediscovered… feel more like research rather than solutions to his questions about synthesizing the visual and the musical within instrument making. Meanwhile Toop offers up three quiet songs which focus on ‘pitch as a function of time’. Like much of Toop’s music (although he also has a noisy side, as well as being an astute and engaging writer) it demands patience and an ability to listen to strange structures of organised sound.

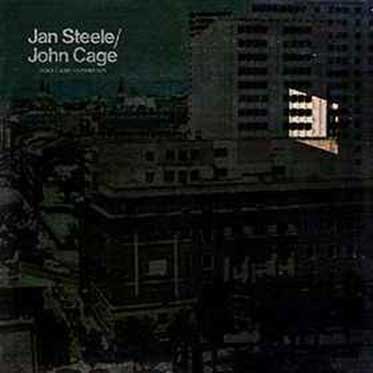

Voices and Instruments, containing music by Jan Steele and John Cage, and the first of the 1976 releases, is one of my favourite Obscure albums. In some ways Jan Steele’s quiet, slow-paced and repetitive deconstruction of rock songs offers up an alternative version of Toop’s music; it too originally arose from improvisations, in this case by the York group F&W Hat. The music is unsettling yet beautiful, soporific but engaging, and the fact that one of the songs – ‘All Day’ – uses a lyric from James Joyce’s Chamber Music provides a link to the John Cage works on side two, one of which also uses words from Joyce. This is sung by the very wonderful Robert Wyatt duetting with a piano, whilst ‘Experiences No. 2’ is a solo vocal piece. Elsewhere Carla Bley sings an ee cummings text and there are two brief piano works opening and closing the set.

I’m less convinced by Michael Nyman’s Decay Music, which contains music from scores that focus upon rhythmic and harmonic systems. ‘1-100’ was originally used to accompany a wonderful early Peter Greenaway short film (which literally shows the numbers 1-100), but here there are four different, superimposed takes which rather muddy the work; I prefer it with the visuals too. ‘Bell Set No. 1’ not surprisingly focuses on the sounds of bells, with an eye to foregrounding the decay and attack of their sound, along with a cluster of other percussion. It’s hypnotic, relaxing but overlong. It’s also the only CD that contains a ‘bonus track’, a faster version of ‘1-100’ played at breakneck speed in half the time. Fun but not at all essential.

The Penguin Café Orchestra are the odd ones out on Obscure Music. Their Music From the Penguin Café finds Simon Jeffes’ quirky and expressive musical sense already fully formed within a mix of dance, world and small group music. It’s music I want to like more than I do, but find too polished and exquisite, too self-aware and afraid to take risks for my liking, something I believe is evidenced by the identikit sound of the Orchestra’s many later releases.

The final three Obscure releases, two years later, saw more of a coherence returning to the series. Machine Music featured works by John White and Gavin Bryars, four ‘machine’ pieces by the former, and an engaging piece for four musicians each playing two guitars simultaneously by Bryars, ‘The Squirrel and the Ricketty Racketty Bridge’, a new version of what was originally a solo piece recorded by improvising guitarist Derek Bailey. This new layered-up and more complex version is wonderful, as is White’s ‘Drinking and Hooting Machine’, which involves the use of bottles to drink from and then produce a hoot from by blowing. Apparently the first take, which involved the use of Guinness bottles, produced chaos, so the five musicians involved had to resort to milk bottles. The other three machines are interesting at first listen but not work I shall return to, unlike the final two albums.

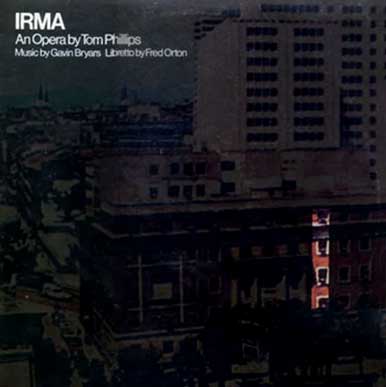

Tom Phillips became a world-famous artist. His paintings hang in the National Portrait Gallery, Tate Gallery and collections worldwide, and he has published several books documenting his projects, ideas and finished work. However, he is probably most famous for A Humument, a project that combines text with illustration and book art. Conceptually rooted in ideas of secret, hidden or found texts within another, Phillips’ book has been commercially available in several new and revised versions, as fine art screenprints and expensive limited editions, exhibited globally and documented online, and also provided its creator with inspiration and ideas for many other works, including Irma, an opera libretto.

However, on this Irma album we find the music attributed to Gavin Bryars and the libretto to Fred Orton (although it feels more like an adaptation of Phillips’ text). There have been other recordings since, which Phillips is on record as preferring, but even with the somewhat uptight and over-organised (perhaps over-produced or over-composed?) feel of this version, it remains an intriguing attempt at turning a conceptual text into an actual recording. It doesn’t, however, compete with the 1988 recording by AMM and Tom Phillips on Matchless.

In many ways Obscure saved the best until last, with Harold Budd’s The Pavilion of Dreams offering up four rich, languid tracks from ‘an extended cycle of works’. Although there had been an earlier album by Budd, of much noisier and more experimental work, this was the key album that introduced Budd to a wider audience and would in due course result in him working with the Cocteau Twins, John Foxx and Bill Nelson, and having albums released through Eno’s and David Sylvian’s record labels. Rooted in mystical jazz, Budd’s music here is spacious and seductive, with marimbas, harps and vibraphones, ethereal choirs and Marion Brown’s amazing alto sax playing, underpinning and entwining around Budd’s skeletal melodies. Bryars, White, Nyman and Eno are all present as musicians here on the final missive from this quirky, forward-looking label.

There are no artists here who did not go on to greater things (although that might not involved financial success or popular acclaim). Their music may have changed, they may have abandoned or started writing critical, conceptual or theoretical texts, they may have moved into soundtracks, the mainstream classical world, curation and/or sculpture, compiled anthologies of music to accompany surreal theses’, or simply continued making quirky, original music. Eno and co. certainly had his ear to the ground and his eye on the ball back then.

As does Dialogo today. This exquisite CD box set (also available as an LP edition) is a work of love, which includes not only remastered music presented in miniature versions of the original record sleeves but the original album notes and a wealth of critical and contextual material, including loads of new photos. Gavin Bryars, who has been heavily involved in this new edition, offers a personal reflection; Bradford Bailer’s long essay offers an ocean-spanning contextualisation for this new music; David Toop and Max Eastley each contribute a short piece on their part in Obscure; and pianist Richard Bernas talks about how he came to play four of the five Cage pieces on Voices and Instruments.

Following the reproduced sleeve notes, there are further, perhaps more obsessive and detailed contributions. Carlo Boccadoro attempts to pin down the enigmatic nature of the Obscure Music and document its ongoing influences and effects; there’s a reprint of an ‘Epiphanies’ contribution to the Wire by Tom Recchion, about the inspiration it gave to him; and then some detailed pieces about the art work and reproducing it, as well as a discography that isn’t quite, but does note the changes, repackaging etc. that followed on from the original editions.

All in all this is an unbelievable and long overdue reissue, one that facilitates listening anew and serious critical reappraisal. It’s well worth saving your pennies and enlivening your brain cells for.

.

Rupert Loydell

More details and music excerpts at https://www.soundohm.com/product/obscure-box-cd

Many thanks for this article and review, there seem to so few places to catch music like this, wonderful and underground.

Comment by Neil Houlton on 27 November, 2023 at 9:24 am