The Complete Works of W.H. Auden. Poems Volume I: 1927-1939

The Complete Works of W.H. Auden. Poems Volume II: 1940-1973

(Princeton University Press, 2022)

Everybody knows a poem or two by W.H. Auden. There’s ‘Night Mail’ and its train rhythms written for an Associated British Picture Corporation film about the GPO back in 1936; what’s often known as ‘Funeral Blues’, movingly declaimed by John Hannah in Four Weddings and a Funeral; perhaps ‘Musée de Beaux Arts’ (‘About suffering they were never wrong’) or the untitled poem which begins ‘Lay your sleeping head my love’.

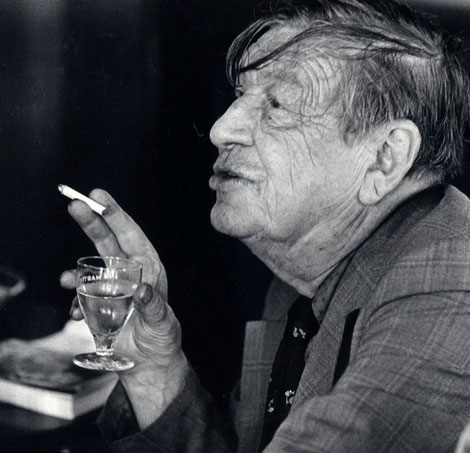

Everybody knows what Auden looked like in old age, too: a man with a wonderful craggy landscape of a face, often with a cigarette in his hand, usually dressed in a crumpled suit. Everybody knows he was gay, and that he was a 1930s poet who was part of an outspoken and militant group of writers responding to what Auden, in his poem ‘1st September, 1939’, called ‘a low dishonest decade’, where ‘Waves of anger and fear / Circulate over the bright / And darkened lands of the earth’. And a lot of people know he moved to the USA in 1940 and later joined the Episcopal church there.

Everyone knows something about or by Auden, and everyone had a different route into his work. For me, apart from the odd poem in school textbooks, it was buying a hardback copy of his final book, Thank You, Fog, in a remainder bookshop on Oxford Street, where it kept company with copies of Slow Dancer magazine, and poetry books by Brian Patten and Francis Berry (all of which I also purchased).

Thank You, Fog , whose laconic ‘final poems’ I am still very fond of, especially the title poem, was later joined on my shelves by a well-thumbed copy of Faber’s 1979 Selected Poems. Well-thumbed by others, not by me, as I was busy chasing what at the time seemed like more exciting and innovative work by the likes of Robert Creeley, Kenneth Patchen, e.e. cummings, Peter Redgrove and Adrian Mitchell. But before too long a good friend of mine would prompt a return to Auden’s writing.

The English Auden, which was subtitled Poems, Essays & Dramatic Writings, 1927-1939 felt like a subversive text when my friend enthused about it, prompting me to buy my own copy. The Orators included (and still does) prose poems, graphics, list poems and journal entries. Elsewhere in The English Auden were songs, speeches, radio talks and essays: ‘Problems of Education’, ‘How to Be Masters of the Machine’, ‘Psychology and Art Today’ and a thorough and extensive, multi-sectioned one on ‘Writing’. The book opened with some kind of drama script, ‘a charade’ called ‘Paid on Both Sides’.

One of the things this opened up to me, apart from some different ways to think about poetic forms and what could or might be regarded as poetry, was a wider context for writing itself, that poetry could be political, sociological, provocative, declamatory, subversive and playful. Or as ‘XXV’ in the sonnet sequence In Time of War puts it, ‘Nothing is given: we must find our law’, ending 14 lines later with the brief summary ‘We learn to pity and rebel.’

Many of the poems gathered up in The English Auden are given a wider context there, as part of an exploration of England and ‘The English’ in the decade leading up to World War 2. ‘Lay your sleeping head my love’ reads differently when it shares a cover with the contents of The Orators, as does the elegiac ‘Stop all the clocks’. They are moments of love and mourning whilst the poet is part of a nation ‘Wandering lost upon the mountains of our choice’, a people who ‘dream of a part / In the glorious balls of the future’ but ‘are articled to error’ and ‘live in freedom by necessity’. (In Time of War, ‘XXVII’)

Although in some ways Auden was conservative (small c), writing a (poetic) ‘Letter to Lord Byron’, engaging with Greek myths and other historical stories, and sometimes seemingly rooted in a traditional view of England and the English, he was also a radical, with the ups and downs of the 1930s leading him to question and critique many cultural assumptions and social hierarchies, often through the lens of communism. WW2 would also encourage poetry which engaged with years of violence, sacrifice, patriotism, political posturing and post-war triumphalism. Auden, of course, was safe in the United States, criticized by many not only for fleeing as war broke out, but also his seeming abandonment of the political left and his adoption of, or conversion to, Christianity.

Princeton University Press’ Complete Works of W.H. Auden editions are beautiful critical editions of his writing, with the two-volume Collected Poems having been preceded by two books of Dramatic Writings, and six of prose. The first volume of poetry contains 808 pages (540 of poems including juvenilia, school poems and abandoned poems, the rest ‘Textual Notes’) whilst the second clocks in at just over 1100 pages: over 700 pages of poems, followed by five appendices and textual notes.

I can’t pretend to have read all the 1200+ pages of poetry, let alone the additional material, but I have dipped in and out, revisiting work I know or half-know, and reading poems I have never seen or even heard of before. It’s accomplished and impressive work, and the notes are informative and interesting in the way academic footnotes often are, pointing out variations and versions, possible meanings or allusions, and offering context and understanding to facilitate informed reading.

Auden is not an occasional poet, nor does he prove the (in my opinion, wrongheaded and incorrect) theory that even good poets only produce a few memorable poems. This is an amazing body of work, composed by a writer who wrote his way through life, always thinking and paying attention. Some of it feels dated in the way it romanticizes life, or alludes to the kind of ideas and literary canon we have now mostly disregarded, but it is also a poetry written in response to the changing world of the 20th Century, documenting and questioning, always willing to challenge and engage with the contemporary.

I keep returning to Volume I, where the voice is less settled, the poetry more surprising and unexpected, although there is also plenty of intriguing and thoughtful work in Volume II. Sometimes, however, this is nestled between more playful and slight verses, such as the 60 poems of ‘Academic Graffiti’. Here’s ’53’ in its entirety:

Thomas the Rhymer

Was probably a social climber:

He should have known Fairy Queens

Were beyond his means.

Witty? Yes, but not the stuff authorial reputations are made of. That will remain because of those Selected Poems many of us know, the more declamatory and experimental work from the 1930s, and the sheer mass of intelligent, thoughtful and analytical writing produced by Auden. Writers write, and Auden did. What wonderful stuff it is.

Rupert Loydell

(This review was first published at Tears in the Fence)

W. H. Auden reading a selection of his poetry 1961:

Night Mail:

I remember Auden talking happily with Hare Krishna devotees after his reading at St George Bloomsbury in the early 70s. Before proceedings he had sat smoking on the church steps while the audience entering stepped around him saying “Auden” this and “Auden” that while totally ignoring his presence. The ‘literary world’ is a strange beast that gets poets wrong while ‘fixing’ them in its canon. Auden’s ‘awakening’ – that he fell out of love through his own poor capacity for loving – led him to re-engage with the Anglican Communion. He felt socialism alone was not enough and Freudianism too narrowly conformist.

Comment by bernard saint on 16 October, 2022 at 5:50 pmWhen hearing that a Halfway House in NYC was threatened with closure he gave money from his literary awards to keep it open. Like many of his generation he seemed outwardly ‘conservative’ while inwardly being ‘anything but’. His near-contemporary John Heath-Stubbs comes immediately to mind.

Yes, I find Auden intriguing, and your response adds to that sense of an interesting writer and person. I’ve always found most [if not all] ‘famous’ poets generous and human, with the exception of the few who believed the publicity bullshit about ‘poetry being the new rock’n’roll’ or that they were doing something so new and intriguing they were above mere mortals. Most writers just get on writing and finding an audience for it…

Comment by Rupert on 17 October, 2022 at 10:48 am