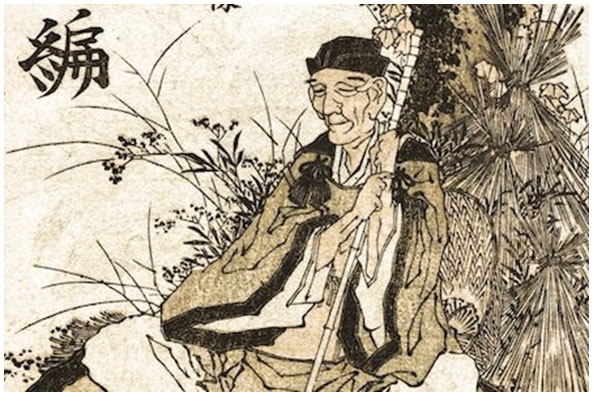

Several weeks ago, when I last visited my friend and fellow poetry enthusiast Kevin Omosele, he gave me a bag from The London Review of Books containing various gems of poetry and prose. Among them was a small, thin book with a worn-out cover. It was the Penguin Classics edition of The Narrow Road to The Deep North and Other Travel Sketches by Matsuo Bashō (1644 – 1694), translated and introduced by Nobuyuki Yuasa. I had only ever read one poem by Bashō, probably the most famous haiku in Japanese literature:

an old pond…

frog jumps in

water’s sound

It is a marvel of beauty and simplicity. The mood evoked by the old pond is one of peace and tranquillity, a stillness that is momentarily disturbed by the leaping frog and returns with the final auditory image of the water’s sound. The haiku can be interpreted in a few ways. The pond could be a metaphor for a certain state of the mind, with the frog being an external stimulus that intrudes upon it but is then subsumed within it, producing a deeper resonance from the soul. It also speaks to the harmony of nature: the frog jumps into the old pond, perhaps not for any specific reason but merely due to a spontaneous impulse, and the water responds with its own language. By recreating this scene in our mind, the poem guides us towards a state of peace and tranquillity within ourselves.

As a Buddhist monk, Bashō believed that poetry had the power to guide its readers towards certain states of mind where the beauty and simplicity of nature can be better appreciated. It is not so different from Keats’ belief in the healing potential of poetry. Whereas Bashō wanted to guide his readers towards a state of inner calm and an appreciation of the beauty that surrounds us, Keats believed that poetry could heal the heart from the suffering and inner sadness that we face as a consequence of our lives. In both cases, beauty is the ideal. They differed, however, in their means of achieving this ideal. Keats reaches it through the musical adornment of language, whereas Bashō strips language down to its purest essence. There is little complexity in Bashō’s poetry, to the extent that if one is not in a peaceful enough state of mind his poems can seem quite meaningless and trivial. But that seems to me the value of his work, in that it guides the reader through its very own simplicity towards a state of mind in which simplicity can be better appreciated.

Bashō wrote The Narrow Road to The Deep North later in his life. It was one of several travel sketches that he wrote following a series of long walks through Japan. The first of these walks was undertaken in 1684 and lasted nine months. He was accompanied by a young man named Chiri, one of his poetic disciples. It was dangerous to travel on the road in Japan during this period, but the two of them managed to make it safely back home. Bashō recorded the journey in the first of his travel sketches, The Records of a Weather-Exposed Skeleton. One of the things that struck me about this journey is his desire to let go of worldly attachments. “I am indeed dressed like a priest,” he writes, “but priest I am not, for the dust of the world still clings to me.” On his return, however, it is the journey that clings to him:

shed of everything else

I still have some lice

I picked up on the road –

crawling on my summer robes.

These two observations remind us to be more self-aware of our mental states when undertaking or returning from a journey. Ultimately, the goal is to reach a harmonious state of unity between the body and spirit. The idea resonates with a remark made by the American transcendentalist philosopher, Henry David Thoreau, in his lecture on walking: “I am alarmed when it happens that I have walked a mile into the woods bodily, without getting there in spirit.”

The Narrow Road was the last of Bashō’s travel sketches. It takes the reader on a journey around Japan, stopping at various landmarks and temples, but it is much more than a travel diary. It contains, as the postscript notes (written by Soryū, a Japanese priest and scholar from the same time period), “not only that which is hoary and dry but also that which is young and colourful, not only that which is strong and imposing but also that which is feeble and ephemeral.” It is true, as he says, that while reading The Narrow Road, there are times when “we feel like taking to the road ourselves, seizing the rain-coat lying near by, or times when we feel like sitting down till our legs take root, enjoying the scene we picture before our eyes.” He goes on to compare the book to “the pearls which are said to be made by the weeping mermaids in the far-off sea”. While this is, indeed, a beautiful comparison, even a regular mollusc-made pearl would be apt – and perhaps, if I dare to say, even more so, since Bashō’s writing serves as an enduring reminder that our reality is more than enough as it already is.

Gilles Madan