2018 marks 50 years since the Revolution of May 1968 which inspired not only the youth of France, but also spread its social and cultural effects to the rest of Europe and the entire world.

Paris, 1968, France protests

.

In its origins, May ‘68 was a rebellion against the suppressing papa-knows-best conservatism of General Charles de Gaulle’s economically booming France. At one level, it was a fast-forward revolution for the inalienable right to wear long hair and colourful trousers. Of course, the main reason that radicalism found easy focus in France was due to the systemic failure to fulfil social reformist demands.

‘68 also came up with a new philosophy of battle: the commune, the barricade and the semi-autonomous areas that allowed the form of collectivism and self-emancipation.

One could argue that, for artists as much as students, ‘68 represented a fight over space. They wanted to free the imaginations of their fellow citizens in resistance to the growingly consumerist nature of the society around them. This was a bold project, as reflected by the famous slogan “La beauté est dans la rue” (“The beauty is in the streets”), that is credited as an inspiration for punk art in the ‘70s and Banksy today.

In turn, the forms of protest music have been determined as a conscious attempt to challenge the structures of the canons. The precise nature of the flourish of ‘60s rock, folk and free jazz music can only be explained by looking at the social change that young people strived for in that decade.

SINGING THROUGH THE BARRICADES (AND BEYOND)

Musically, France’s signature sound was developed in the Café chantant. Protest songs were common as part of the cabaret and artists, like the poet Jacques Prévert, expressed left-wing ideas in their lyrics. Later on, the French pop scène, grouped as the Yé-yé movement, imitated what was happening in England. But other, more anarchistic singers, started to mix elements of chanson and folk with the new pop and rock music. Collette Magny was one of the first who took up political themes in her songs when she protested against the war in Vietnam ‘67.

By ‘68, rock music turned out to be the soundtrack for young rebels. Renaud wrote “Crève salope” which would become the soundtrack for the riots in May, although never officially released. Claude Nougaro recorded “Paris mai”, the chansonnier Leo Férre teamed up with the prog rock band Zoo for the songs “L’Été 68”, “Paris, je ne t’aime plus” and “Amour Anarchie”. Folk and experimental jazz developed in the hands of Brigitte Fontaine and Jacques Higelin. Catherine Ribeiro & Alpes, Bernard Lavilliers, Gerard Manset and, most notably, Serge Gainsbourg, a Parisian hybrid of Woody Allen and Bob Dylan, laid the basis for what would become internationally known as la chanson rock.

Even though at a political level ‘68 was a bit of a failure, its impact was huge. Like a prolonged echo, the effect on French pop and rock came almost ten years later when punk reached France. Artists like Jacno, Elli Medeiros (from Stinky Toys) and Telephone, who walked in the protest of ‘68 as youngsters, took the next steps in creating French pop and rock, which gradually developed in the French Punk and 80s New Wave. But the spirit of May ‘68 lived on and inspired the work of many foreign artists. For example in England, ‘89, The Stone Roses’ song “Bye Bye Badman” from their eponymous debut album — considered nowadays as one of the most significant ever — was inspired by the riots in Paris. Even the cover had the tricolore and lemons on the front, which were used to nullify the effects of tear gas fired by the police. In Sweden, the punk rock group The Refused released the landmark “Protest Song ’68” about the revolts. Also, the music video for the song “I Heard Wonders” of the Irish composer David Holmes was based entirely on the ’68 protests, as was the concept album Storia di un impiegato by the Italian singer-songwriter Fabrizio de André. The Greek composer Vangelis, who became famous worldwide for his film scores, released the album Fais que ton rêve soit plus long que la nuit, influenced by that volatile period containing sounds from the demonstrations, songs and news reports.

LE… FREE JAZZ…HOT

In France, few genres were as closely linked to May ’68 as free jazz. Certain groups who adopted the style (such as the Cohelmec Ensemble), or borrowed heavily from it (e.g. the rock band Red Noise), further supported the perception that a subterranean relationship existed between the impulsive character of the protest movement and the improvisatory nature of avant-garde jazz. Free jazz musicians were among the most active members of the strike, forming the core of the group Action Musique. Free jazz appeared to cover the events of May and has remained highly visible in subsequent years. This may seem surprising, given that the movement was both relatively new to France and widely perceived as somehow inaccessible.

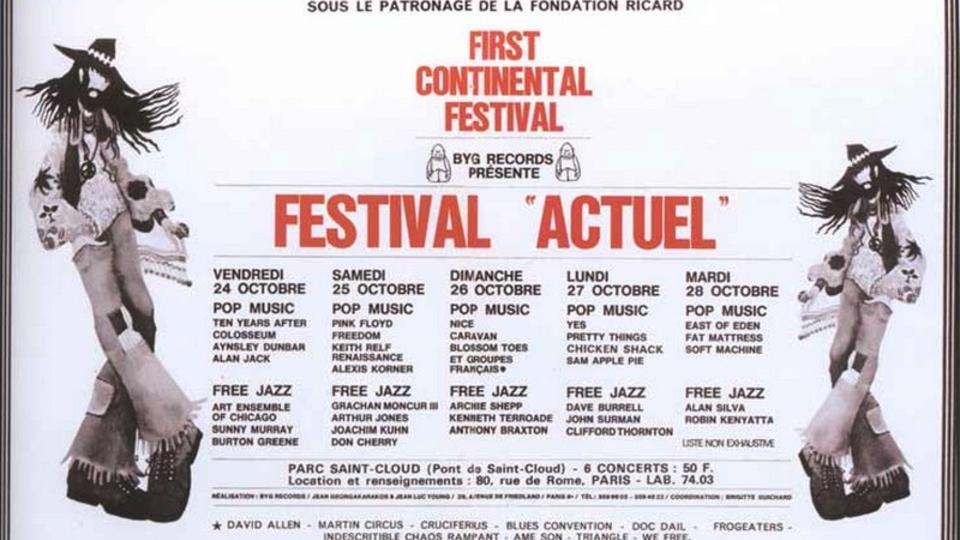

And, yet, the assumption that free jazz would prove too disturbing for the public was disproved. Reports from the late ‘60s make references to auditoriums packed with a young and enthusiastic audience. The heightened demand for free jazz was stimulated by such an increased supply that even some American jazz musicians, including Sunny Murray, Alan Silva, and the Art Ensemble of Chicago, decamped to France in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. The burst of activity that began in July and August ‘69 culminated in October at the Actuel Festival, arguably the apogee for free jazz in the country.

Increasingly dynamic, French jazz has a lasting effect on the European — and even American — music scene. As the internationally renowned jazz pianist Laurent de Wilde stated in NY Times “European jazz has liberated straight-ahead jazz from its harbour and has sailed away”.

Europe Finds Inspiration

‘68 was the time when the cheerful mindset of the previous five or so years started to give way to disillusionment. Demonstrations in Paris and other places across Europe, transgressed the ideological fronts of the Cold War. That year was also the starting point for many countries to develop their local music scene.

Singing in the native tongue became a form of protest in several countries, sometimes because the use of local culture and language wasn’t openly supported (like in most former USSR countries) or, at other times, because protest songs were made in the local language to have more impact, like in Czechoslovakia, where music served as a way of protest after Soviet-led troops crushed the Prague Spring, earlier in ‘68.

At other times, the difficulty in booking international acts to perform (e.g. riots in Rolling Stones and Jimmie Hendrix concerts) fuelled a local rock scene, like in Italy. There, the Sessantotto period (“years of lead”), which marked the battle between students and the police, and the political events that occurred were reflected in the music of prominent local figures, such as Piero Ciampi, Fabrizio de André and Adriano Celentano, whose recording on “Una carezza in un pugno” (A Caress into a Fist) became a protest anthem.

Even under the dictatorial regimes of Spain (read up our fellow’s Marco Molinero’s insightful piece here) Greece and Portugal, musicians sought the edges of the allowed folk music to see if they could mix it with modern trends.

Ultimately, a popular culture emerged, inspired by new aesthetics, joined with hippie ideologies and melted into a set of symbolic forms. Let’s see some examples of what happened and, maybe more interestingly, what did not.

ENGLAND: THE OTHER SIDE OF 1968

“Everywhere I hear the sound of marching, charging feet, boy

’cause summer’s here and the time is right for fighting in the street, boy…”

(Rolling Stones, “Street Fighting Man”)

Mick Jagger commented on “Street Fighting Man” in an interview :“(This song) was a direct inspiration (of May ’68 in Paris), because by contrast, London was very quiet… It was a very strange time in France… I mean, they almost toppled the government in France; de Gaulle went into this complete funk, as he had in the past, and he went and sort of locked himself in his house in the country…”

It is practically impossible to understand the youth protests of the ‘60s without appreciating the importance of popular music in this decade. Although the music and ideology of liberation were closely linked in other countries like Germany or Greece, which were under huge political turmoil, evidence was abundant that rock music failed to provide the matches to ignite a similar revolt in England, even after Enoch Powell’s “River of Blood” speech on mass immigration. Instead, developments demonstrated that rock music could be a significant cultural force without necessarily being a revolutionary one. “Street Fighting Man” might have been a staple of the anti-war movement of the 60s, but it was an isolated example.

British music was as free-spirited and culture-shaping as American rock, and perhaps more, both in terms of pushing the boundaries of art and addressing inflammatory social subjects in new ways, like with The Kink’s “Lola” (transvestism). However, it was not drastic in the sense that it challenged the state — at least, not directly. Most prominent figures in the British counterculture were largely idle towards political revolt, with rare moves by a few musicians, like Pete Townshend, who became more active at the end of the decade, and John Lennon, whose politics exploded when he left The Beatles.

The larger legacy of ‘68 in the country was the conviction it gave some musicians that popular music needn’t be ephemeral. For example, Yes expressed through the next decade a utopian social view. And almost all of the entire progressive rock movement, from Genesis to Van der Graaf Generator, mostly explored a dystopic future that matched the denial of almost everything in the punk rock movement that followed.

GREECE: PROTEST, MUSIC AND THE LOST CHANCE OF GREEK ROCK

‘68 was the second year of the military junta of ‘67-’74 and it represented the dark ages of Greece’s modern history. Due to censorship, the May ‘68 protests did not exist to the Greek media. The news was finally broadcasted by the Greek programs of BBC and DW and was received with hope that something was finally happening, although it was happening somewhere else.

In terms of music, there was a flimsy rock scene imitating foreign groups and the romantic lyricism of the so-called “new wave”, led by Manos Hatzidakis and Nana Mouskouri, that copied to some extent the French chansons and made them popular. An interesting exception was Dionysis Savvopoulos, a prominent music figure; in his song “Vietnam Yé-Yé” the French culture was linked to political subjects and circulated an ambivalent message.

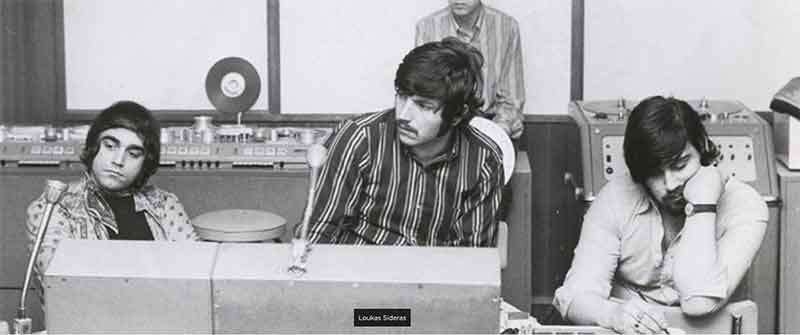

Another exception was Aphrodite’s Child. In an effort to leave Greece to avoid the censorship, the band was on their way to London when they got stuck in Paris partly because of the strikes associated with the ’68 events. Their song “Rain and Tears” was played during the riots in France and became an overnight sensation.

Theodorakis’s music, as well as Yiannis Makropoulos’ and Nikos Xylouris’, was never officially allowed by the dictatorship, as well. Theodorakis was jailed and, eventually, exiled in Paris (following a solidarity movement for his freedom led by Dmitri Shostakovich and Arthur Miller, among others). There, along with fellow activist and actress Melina Mercouri, they fought for the restoration of democracy in Greece.

What is interesting is that there existed a time lag in the music inspiration. Compared to other countries, where punk emerged in mid-70s, Greece only saw it spread in the early ‘80s. New Wave became popular in late 80s. The reason was, following the riots in the Athens Polytechnic in ‘73 and the collapse of the junta in ‘74, the social driving forces were not strong enough to ingrain the cultural transcendence that was taking place elsewhere. There were some efforts, though, e.g. the club Kyttaro — the “Greek Marquee” club as the international press called it —, a landmark for the Athenian underground rock scene. Rock acts frequented the club like Socrates Drank the Conium, Poll and Pavlos Sidiropoulos, who had an important local impact but found themselves unable to spark the birth of a lasting rock scene. Greek rock had a chance to grow and become an integral part of the international music scene, and right there and then, lost it.

GERMANY: FROM THE 68ER-BEWEGUNG TO KRAUTROCK

– by Daniel Cole

The 68er-Bewegung, movement of 1968 was an integral moment in German history. Faced with a conservative government, and the legacy of its right-wing past not properly addressed yet, impoverished youth groups led by their charismatic (and to be martyr) leader Rudi Dutschke took to the streets and battled authoritarian state militia, and media. It was through these radical actions, that Germany’s left-wing ideological roots really took hold.

The reformist protests were dominated through student uprisings, and lead through the Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund (a.k.a. the Socialist German Student Union). The right-wring press tried to take on the students with inflammatory articles, through the work of publisher Axel Springer and such media outlets like Bild-Zeitung. It was in Easter 1968 that Rudi Dutschke was assassinated, shot by a right-wing sympathiser (although he survived, he would die 11 years later from his injuries) leading to an escalation of protests, and fighting on the streets.

These protests and movements were integral to re-shaping the social infrastructure of Germany, castasising its conservative and radical national-social past to the history books once and for all. Political groups and interaction grew, and decrees were enforced to make sure new public service workers upheld free and social policies – many politicians of today were involved in these actions. It even influenced the sonic aesthetics and music-cultural landscape of of today, influencing student scenes, and radicalising scenes through anti-conversative sentiments. During the Internationale Essener Song-Tage bands like Tangerine Dream, and Amon Düül put down the framework for the burgeoning krautrock scene. In Berlin, Conrad Schnitzler was doing things with electronics of which no-one had heard anywhere in the world, of which the founding members of Kraftwerk were paying very close attention to.

Almost half a century on and the liberal, anti-authoritarian sentiment can be heard throughout the likes of experimental acts such as Christoph de Babylon and T.Raumschmiere, and Mark Ernestus – children of the 60s movement, with an extended history that also lived through the country’s reunification. On a more mainstream level, pop artist such as Peter Fox still embody this protest sentiment, in a scene where hip hop and reggae, as appropriated through the German, immigrant youth, has become the voice of disenchantment, and unrest.

PORTUGAL: FEAR AND INSPIRATION

– by Amorim Abiassi Ferreira

In ‘68, Paris was the go-to place for the exiled that came from Portugal. The big movement started five years before and it’s estimated the population, at that time, ranged from 200,000 to 300,000 emigrants. People that worked the fields in their home country now worked on construction sites and lived either in bidonvilles or, like my parents, grandparents and great-grandparents, on cramped maid’s quarters on the last floor of buildings.

Censorship reigned over any kind of print and art during fascist reign, but the Portuguese media published a lot on the Parisian revolution of May ‘68. Their objective: to show a dangerous and turbulent world that was in opposition to our calm and moderate country. A year later, Coimbra, one of the world’s oldest universities, was also the stage of a student uprising that was firmly shut down. On the contrary as to what happened before, communication about the strikes was absolutely censored.

Although the revolution instilled fear in many, it brought inspiration to many more. Musicians like José Mário Branco, Sérgio Godinho or Luís Cília all lived in France when May ‘68 happened. They became some of the most famous names of the Portuguese intervention music scene. Six years later, fascism would fall in what became the historic 25th of April, now called the Carnation Revolution. Music played a crucial role; twenty minutes past midnight, “Grândola, Vila Morena” was heard through the airwaves. That was the final confirmation that the revolution was starting.

WHERE’S THE REVOLUTION?

The revolution of May ‘68 would eventually come to an end. The Situationists would splinter, many of the student leaders, who previously threw bricks against the system, now lay bricks to build an even stronger system. What lasted are its images and slogans — dangerous in their poetry and music, inspiring in their dare. In that sense, May ‘68 is a testament to the power of art itself. Visions driven by authenticity speak long after the tear gas has receded and the illusion of normalcy returned.

The archive of the international underground has in recent years been recovered and made available in a new kind of space: the Internet. The speed and low cost of its digital distribution would have delighted many of those who were active in ‘68; the Internet, and the “free culture” that it enables, represents a creative commons that, in a sense, fulfils the dreams of 50 years ago.

It’s obvious from controversial work being produced by legions of hackers and interventionists across the world that ‘68 is a cluster of ideas rather than a singular event, a vigorous energy rather than just a date to commemorate. One could argue that ‘68 fascinated alternative media, self-expression and new forms of art, becoming more relevant in 2018 than ever before.

And, perhaps Jean-Paul Sartre was right when, reflecting on the meaning of the ‘68 uprisings, he argued: “What is important is that the action took place, at a time when everyone judged it to be unthinkable. If it took place, then it can happen again.”

Leaders of the world, are you listening?

An excellent, trustworthy, account. Explains why the aesthetics born in the sixties are waiting to be taken up by another generation. May the young Carlos Fuentes live for ever!

Comment by Cy Lester on 20 October, 2018 at 10:38 amPerhaps modesty prevented a mention of IT’s own Mick Farron who may have already have been radicalised but The Social Deviants and Deviants set the trend of playing outside the wire of ticket only festivals that was carried on by The Pink Fairies, Hawkwind and even Motorhead. Also Screaming Lord Sutch carried on his major pre ’68 Youth Party policy of reducing the voting age that succeeded in 1969 / 70. A wonderful walk down memory lane however.

Comment by Raymond Church on 22 October, 2018 at 5:47 pm