Saturday. 6th June. Midnight. Psyrri.

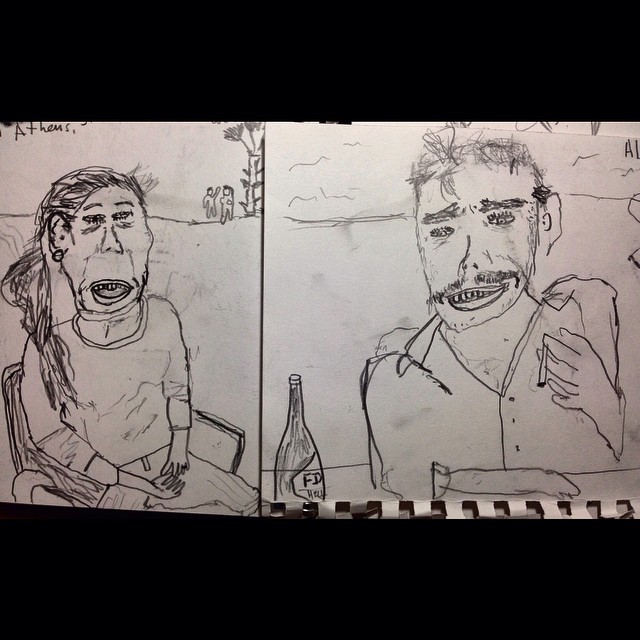

By midnight things were slightly hazy, and although the night went on till morning, I cannot remember many specifics about my dinner with Athena. We sat opposite each other on a single table outside a small restaurant. There were a few plates of food, four perhaps; I can only really remember the pasta, but there were other, more Greek dishes as well. There was a sturdy glass bottle of raki, periodically taken away: once we had poured its contents into our miniature glasses – the kind the British shot and the Greeks sip – it was then returned refilled to the bottleneck. The drink is one reason so many particulars of this dinner escape me, the dizzying effects of a day of bleaching sun another, and my woolly mind perhaps the primary cause.

The memories I do have are a little more impressionistic, yet I’m left with a resounding sense that this dinner must have been one of the most pleasant evenings of my stay. Athena had just finished her PhD in law. “I’m an academic”, she tells me, identifying herself in that broad church of non-fiction writers. Perhaps she had a craftsman’s approach to ideas, taking pleasure in both neat structures and their artful demolition. For example, when I told her about my film (our original reason for meeting), she summarised my ideas neatly, pointed out the problems I would likely come up against, and the potential flaws in my approach. All with a brilliant quiet humour, muted but in no way condescending. She is a brilliant mixture of charming and sensible, and states her own views with earthy clarity. This evening we chatted and gossiped more playfully about… I can’t remember exactly what, other than us laughing frequently and talking loudly.

Sunday. 7th June. Sometime after 2am. Athens Polytechnic.

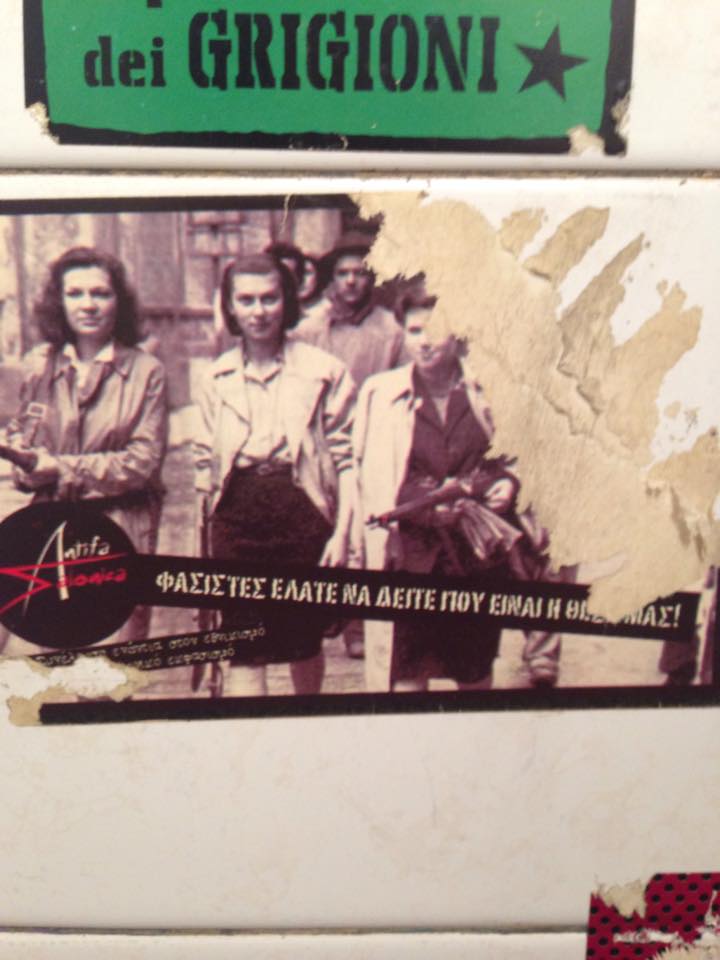

After the restaurant was closed we walked in the same direction – Exarchia. It wasn’t long before we could both smell tear gas. In the middle of the otherwise deserted road, some police were leaning on their shields, their young faces full of stony idiocy, their radios bleeping like a sci-fi flop. I nervously insisted on crossing the road, but Athena said there was nothing to worry about. As we came closer to the university we caught sight of some burning bins, tipped on their side by the entrance to the university in the middle of Stoumari Street. They were set alight to dampen the clouds of tear gas. I went to take a picture of one on my phone but Athena stopped me: “Be careful. These people don’t like photos, and I don’t know who they are.” Photojournalists in Greece have consistently bedded down with the reactionary media – painting revolters as treacherous koukoloforoi (hood-wearers) – and as such, have earned themselves the position of a legitimate target. Amateur snappers too are viewed with, at best, suspicion.

All of this street action – it didn’t exactly sober me up; but the addition of some adrenaline spurred in me a drunken sense of submissive invincibility that made me want to explore. Athena wanted to go to bed, so she gave me a hug goodnight, told me to look after myself, and left. I hadn’t made it yet to the university. Along the street the shopkeepers were tearing up marble slabs, collaborating with the anarchists, perhaps choosing the ideal slab to be smashed up and thrown. The middle of the road was filled with huddled groups of people chiselling out new missiles. Loud rave music blared from one of the top-floor flats, and people lingering outside the door protectively. The atmosphere was tense but friendly. When the gas was too much they dragged a few of us inside to recover for a bit. Upstairs the party was roaring and packed, I nipped in to see the view from above, then returned to the street.

The gates of the university were crowded on either side. Inside there was a huge clubnight in the campus square, the fantastic music shaking the whole neighbourhood. Outside, the front line faced the advancing police. Back and forth it went all night between both sides. The anarchists pushed them back with petrol bombs and stones. The police ran forward to fire a rogue canister of tear gas into the university, attempting to spoil the fun. They were met with petrol bombs and promptly retreated. The anarchists pushed them back with burning bins. I followed as they moved the front line a bloc or two forward. They started making noise – chanting together, shouting, banging the bin, smashing alarms, striking lampposts – to embolden their attack. After a while a stalemate was reached, and I returned.

The crowd consisted of people defending the university and partygoers. All of them looking around to make sure everyone was coping with the gas. Tear gas feels a bit like cutting an onion, and a bit like a hot chilli. Your eyes water, your nose runs and a stinging pain rakes the back of your throat. In my experience, mild amounts can be slightly pleasant. After the Gezi Park protests in 2013, Turkish activists even embraced it singing “tear gas, olé, tear gas olé, tear gas olé”. A shared community of pain can bring people together. However, too much for too long can give you a headache and make you feel nauseous. Smoking cigarettes helps, but so does having smoke blown in your eyes. As I loitered around the gates with some Karelia cigarettes, various crying Greeks approached me asking to have smoke blown in their eyes. There was something very sweet about such a gesture; a typical sign of disrespect temporarily becoming an expression of intimate solidarity.

In the courtyard inside the university, revellers danced and crowded around decks and a sound system in the middle of the basketball pitch. Above were some billowing translucent sheets of fabric lit up by colourful lights installed for the occasion. The music changed throughout the night, the only song by name I remember being ‘A Forest’ by The Cure, but there were a few gothy punk tracks, as well as some hip-hop, amid a mostly House-driven night. The bar served cheap drinks and also provided lemony water to those suffering from gas. The widespread concern for the wellbeing of those around you, and the light-headed feeling from the constant mild pain, created a fertile atmosphere to emphatically dance.

Sunday 7th. June. Afternoon. Psyrri.

Tasos invited me to the general assembly of Embros, an occupied theatre, a little ‘colony of Exarchia’ in the ‘consumerist’ neighbourhood of Psyrri. The bar here is donations-based so you can get a drink for free if you need. They organise clubs, plays, dances, talks, It was squatted in 2011 by a group of artists and over the years has steadily become more anarchist, more or less in correlation to the police repression. It’s a beautiful old building – a fascist printing press in the 1920s, Tasos tells me.

About 400 burgundy leather chairs accommodated around 25 attendees. Some coffees. Some beers. Many ashtrays. The ceiling was obscured by clouds of smoke dimly pieced by shafts of light from above. Nobody looked under 25, but there were a wide range of ages in the room, perhaps averaging mid-30s. The anarchist all-black standard I’d grown used to was eschewed in favour of more thespian outfits. Snugly in the front row was a small woman wearing a red headscarf, white lace and long black beads, looking like the kind of person who smells of mothballs and slips gin into your tea. A remarkable number of the older men wore long, well-stroked white beards, sandals, and unbuttoned linen shirts, softly billowing like togas. There is no sense that it’s rude to talk when others are talking. In the main, whoever is speaking is heard, but always with chatter in the margins. The discussion became animated. With my own weak English assumptions I asked “What are they arguing about?”

“They don’t argue. They agree.” Tasos explained.

Tuesday. 9th June. Evening. Exarchia.

After a long day at the library, Elsa and I meet up at Mikro. A German company is paying her to write an article about citizen-run health clinics in Greece, and she’s spent the day visiting them, interviewing the skilled and unskilled people that volunteer there. They want to close, she tells me, so as to not do the state’s work for them, but it’s difficult to do so as they’re badly needed. There’s a marked absence of English-language reports about these clinics. I have previously tried to find out what I could on them, but to no avail. The conversation switches to more flippant and personal topics, as we chat about our childhoods, silly homespun theories, and her career as a clown at children’s parties. Some friends join us. It’s my last night and various friends come to visit us.

A couple of us go out spray painting around the area – “there’s no police in Exarchia!” I confidently state. It’s difficult to find a wall that is not completely covered in layer after layer of poetic political messages, names of lovers, of activist groups, murals, event details, and a wide variety of anything anyone would think to put on a wall. I wanted to write a line from a song written by my friend, Jamie, who was like a brother to me, and died a year and a half ago. He would have loved this place very much. It’s the agonised chorus from a song by Dogfeet his band, called ‘Putti’. In large part inspired by the 2011 England riots, it chants over and over: “We were nothing before the fire”. On the shoulders of a friend with a bad back, I manage only “WE WERE NOT BE4 THE FIRE”, before falling down. But it seems fitting.

In an alley we’re spraying a friend is grabbed by a lone policeman. Caught in the act. I briefly manage to separate them but he has a large semi-automatic that I soon find myself looking down the barrel of. It’s seems an insane gesture to wave a gun in my face. He wouldn’t possibly shoot, I think, so I tell my friend to run. She refuses on the sensible logic that if a man’s waving a gun in your face you don’t try to run away. As she’s led onto the main road she manages to give me her bag and phone and tells me to run. I take it to another friend, now on a parallel street, and tell her to take it away. Returning without anything incriminating, I find her being cuffed, searched and thrust against a wall. As I approach, the gun is pointed at me again and I’m told “BACK!” Given how insanely trigger-happy this guy seems, it’s almost a relief when other police arrive who appear less likely to immediately shoot us.

In the back of the police car, Ruby asks me to scratch her ear. She screws up her face in wry resignation: “that guy really enjoyed arresting me… Yup… A very aggressive man.” She thanks me for coming with her, but then realises that it’s probably just all for the diary anyway. We try to view the situation ethnographically, making bitter jokes to check we’re both okay. Looking outside, we see that we are being given presidential treatment. A whole convoy of police motorbikes and cars surround us. There’s a strange solemnity to having so many cars transporting you, but it also added a certain misplaced gravitas. My main worry was that we’d be beaten up at the station, the second that I would miss my flight home in the morning. I caught the eye of a couple of the motorcyclists, who were trying to stare me down whenever we stopped.

At the station we were taken into an office upstairs, and ‘looked after’ by a higher ranking office – a stout chain-smoking man who looked dead behind the eyes, but was friendly enough. He gave Ruby a cigarette, and told her that if she had any incriminating photos to get rid of them now. He also let us order souvlaki to the station. It was a very long night. We were all drunkenly lethargic, sat in the same tiny overheated room until after sunrise, gazing at every little detail in the room. We sat under a picture of Jesus, opposite some incomprehensible racist cartoon depicting Chinese criminals, and a quaint collection of Greek nature books. We’re let out

Wednesday. 10th June. Morning. Gizi.

Delirious and tired. The brutal sunrise felt awkward. Too bright. We were very tired. On returning home we shut all the blinds, and put on a pot of coffee. I had only a couple of hours before having to fly home. When we were alone, my friend Xrisa gave me what I later understood to be, I think, the nicest gift I’ve ever received. She had been a culture correspondent at a famous Greek newspaper for eight years, and had a very intimate knowledge of contemporary Greek culture. Like most journalists she had been laid off and was currently searching for a new calling.

Anyway. She was very touched by my enthusiasm for Exarchia, and gave me a CD of Nikolas Asimos and a rare first edition of Katerina Gogou’s poems. Asimos, a singer, I have not really investigated. Gogou, however, has been a revelation. Both were in Greek, untranslated, and so she translated all the lyrics and poems into a red notebook made with a title page “the songs and words at the beginnings of Exarchia”.

The poetry of Gogou, 1940-1993, defined post-Junta anarchist Exarchia. I close these diaries with her beautiful dedication to anarchy:

“Don’t you stop me. I am dreaming.

We lived centuries of injustice bent over.

Centuries of loneliness.

Now don’t. Don’t you stop me.

Now and here, for ever and everywhere.

I am dreaming freedom.

Though everyone’s

All-beautiful uniqueness

To reinstitute

The harmony of the universe.

Lets play. Knowledge is joy.

Its not school conscription.

I dream because I love.

Great dreams in the sky.

Workers with their own factories

Contributing to world chocolate making.

I dream because I KNOW and I CAN.

Banks give birth to “robbers”.

Prisons to “terrorists”.

Loneliness to “misfits”.

Products to “need”

Borders to armies.

All caused by property.

Violence gives birth to violence.

Don’t now. Don’t you stop me.

The time has come to reinstitute

the morally just as the ultimate praxis.

To make life into a poem.

And life into praxis.

It is a dream that I can I can I can

I love you

And you do not stop me nor am I dreaming. I live.

I reach my hands

To love to solidarity

To Freedom.

As many times as it takes all over again.

I defend ANARCHY.”

————————————————————————

These diaries are dedicated to Mike Lesser, without whom none of this would have been possible.

Heathcote Ruthven