Blood, Sweat & Chrome: the Wild and True Story of Mad Max: Fury Road, Kyle Buchanan

(hbck, £20, William Morrow)

I persuaded my friend Pete to come and see Mad Max: Fury Road in the first week of its UK release. Of course, he’d seen the first three on TV late night re-runs, but he wasn’t – ok, neither of us were – prepared for the full-on mayhem of the fourth instalment on a big screen. ‘What the hell was that?’ said Pete as we emerged blinking into late evening sunshine, deafened and overstimulated by car crash after car crash, special effects after special effects, not to mention fight scene after fight scene. ‘What happened?’ he asked, again hoping for an answer that didn’t come, since I didn’t have much of a clue either.

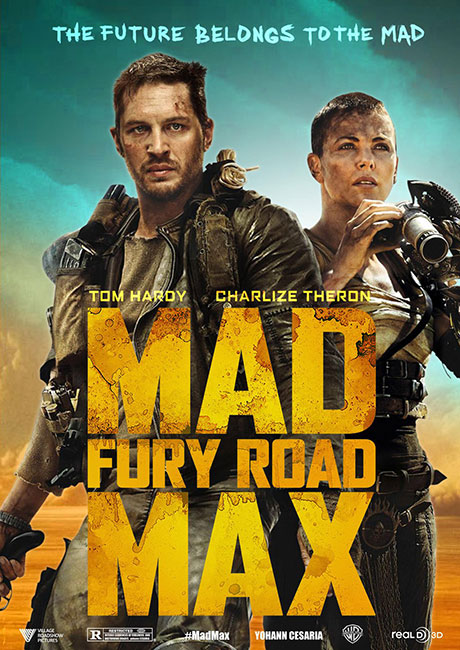

Fury Road is basically two long chase scenes back to back. Max, this time played by Tom Hardy not Mel Gibson, escapes from a warlord’s desert fortress and runs away, teaming up with escaped members of a breeding harem (led by Charlize Theron’s character Furiosa) on the way. Together the group continue on to a kind of promised land, The Green Place, a desert oasis town where Furiosa grew up, only to find it has become desert. So back they go, all the time battling with the warlord’s War Boys: troops who they also fought on the run out. It’s live-action mayhem, full of extreme cartoon violence, crazy cars and weapons, huge desert- and weather- scapes, energetic jumpcuts and camera shots from all angles, with the absolute minimum of dialogue or explanation. This is post-apocalypse pandemonium; engaging, awe-inspiring, loud, ridiculous, engrossing over-the-top dystopian pantomime. No wonder it was a box-office hit and audiences have been promised another episode – supposedly a prequel about Furiosa – before too long.

What wasn’t obvious from the film, but this book explores, is the epic story of how George Miller managed to make Mad Max: Fury Road despite having studio backing pulled, logistical and technical issues, difficulties filming in the Namib desert, and casting and personality clashes. Kyle Buchanan has undertaken hundreds of original interviews and collated quotes, opinions and information into the story behind the film, a film that never had a script but was filmed from a 3500 frame storyboard drawn years before shooting began.

It is a story of tenacity and sticking-to-your-guns, a story of dedicated stuntmen, cameraman and prop makers. A story of engineers dedicated to constructing makeshift cars from salvage; actors prepared to shave their heads and live out their characters’ obsessions in the unbelievable desert heat, sometimes layered in masks and leather; photographers prepared to film whilst hanging off high-speed vehicles as they crash into each other; and colleagues of Miller’s bending the rules or playing games. One of my favourite stories in the book is when a hundred or so vehicles plus equipment (72 containers full!) are put on a boat to Namibia even though the studio have said that it is too risky to film in Africa.

Chris deFaria [producer]: ‘I remember a studio executive going, “What the fuck are you fucking talking about? The cars are on a boat?” Doug [Mitchell, producer] goes, “Yeah, the cars are on a boat and that boat is going to Namibia.”‘

Kelly Marcel [screenwriter]: ‘Doug doesn’t give any fucks. Zero, zero, zero fucks. You can’t fight with someone who doesn’t give a fuck if you’re not going to make their next movie or not. You have to be like, “I’m doing it.”‘

And Miller and his team were doing it. And did. Living as a temporary community taking over a small desert town, miles from anywhere, they had to learn to handle freezing nights, high temperatures at noon, dust storms, muggings, burglaries and isolation, not to mention working together. They learnt to live in close proximity, even on their days off, travel in groups to avoid violence from the locals, and accidentally started a small glamrock revival because the War Boys’ black eyeliner wouldn’t properly clean off their faces: ‘as we got towards the last two or three months’, says stuntman Harrison Norris, ‘all the locals in town […] were wearing guyliner as well. We accidentally glam-rocked the shit out of that place.’

The book is full of quirky stories and events like this, as well as those more pertinent to the film getting made, with lots of personal memories and insights, but thankfully it rarely sinks to gossip. The nearest it does is the recently resurrected and widely publicised disagreements between Tom Hardy and Charlize Theron. Since the book is an approved one, it feels very much like a deliberately highlighted and topical story which has been carefully mentioned to the press again, and seems to derive from Hardy’s method acting (living in character) and being prone to bad timekeeping, whilst new mother Theron wanted to get back to her baby. In the end she confronted him about being three hours late and got sworn at and threatened for her pains, resulting – she says – in her feeling scared.

With hindsight, it’s clear this wasn’t dealt with very well on set but that there were other things going on. Marcel says ‘I’ve been on some crazy sets and been involved in some fraught movies, but this is unlike anything I’ve ever experienced in terms of sheer determination and grit and scraped kneed and bloody injuries and tears and frustration’, whilst video assist Zeb Simpson declares ‘[t]his was a once-in-a-lifetime job’. Producer George Miller states that ‘we’d still be there if we could, except they took away the cameras and we’ve wrecked all the cars.’ Despite all the problems over many years, Mad Max: Fury Road was both a critical and commercial success, attracting huge audiences and nominations for awards and as film of the year.

Miller’s refusal to compromise, be that on where to shoot, how to shoot, budget restrictions, design aesthetic, or any dilution of his vision, the film he saw in his head, resulted in an astonishing and original film, perhaps one of the last action films not constructed using CGI, which is what gives it such a visceral presence on screen. This beautifully designed book offers illuminating insights into the whole creative process, from conception to final edit, via the technical, social and machinations of the film industry. The only book it might be compared to is Eleanor Coppola’s Notes: The Making of Apocalypse Now, and it is just as exciting, readable and important a document as that.

Rupert Loydell