3. The Theatre Wardrobe

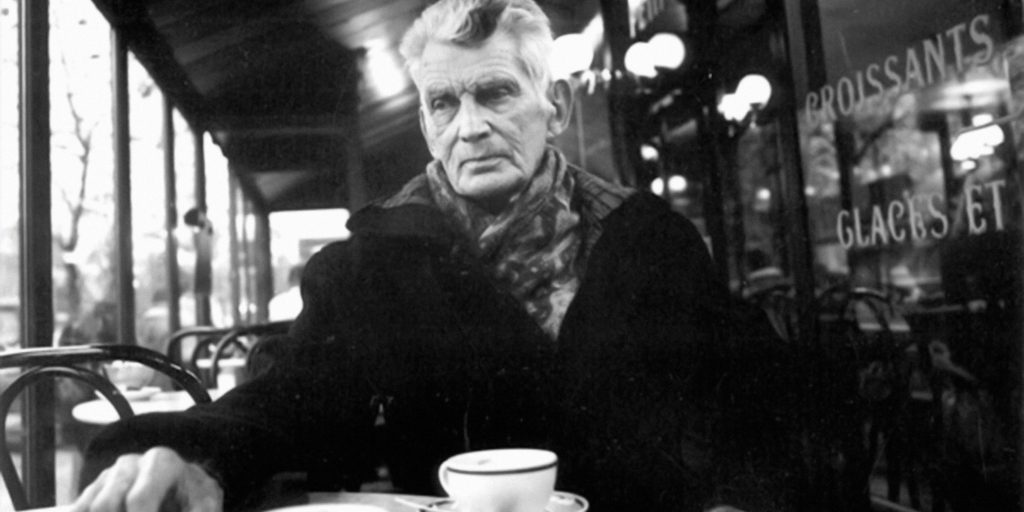

SAM THE PLAYWRIGHT

I must have slept deeply. I needed to distance myself from what is going on and the feelings of disappointment that continue to threaten me to the point of annihilation. I dreamt the painter Bram van Velde, my dearest friend and the man most akin to me, was playing Krapp. He was wearing a black and white clown’s costume made of white diamonds and black jet. A cosmic battle raged through his being, the gems pulsating light and dark. Old Nick stood behind him, disguised as a stagehand, head to toe in blacks that make him almost invisible. I am unable to speak, knowing Bram is in danger and that words cannot help him. I am heartbroken by his predicament. He didn’t open them, but his eyes focused on me, two black burning coals all seeing, penetrated by fear and hatred, yet I know he is full of felicity and acceptance.

Exhausted by my dream, my tired half-open eyes take in the room where I’m sitting. Sight and sounds are clear and distinct, and at the same time distant. The old leather armchair is comfortable, a bed folding itself around me. I gradually allow other shapes to come into focus. Momentarily the image of the work going on downstairs comes into my mind but I decide to banish this. Feelings of bewilderment and betrayal can still be hot in me. They are partly directed at myself.

I turn my attention to the dimensions of the space in which I have placed myself after escaping the painful chaos downstairs. Does the room seem smaller or larger because it contains so much? There’s a lot of clutter. I won’t let that disturb me or press on my active consciousness. Clutter gets in the way of form created by empty space, blotting out essential aspects of experience if you let it, and I need a clearing at this moment. Scanning the room, I’m aware of a shift up to the right so that the whole room slopes to the left. I take in the room at this angle; it is as if the whole building has tilted, and yet all the contents, including myself, remain upright. The outlines of the machines in front of me, and a woman sitting at a sewing machine, are as if suspended. There is an open door on the right creating another distorted rectangle, a quadrangle with large side outwards, which gives permission to further scan from my perspective, audience left to right, the visual components of my geographic position. I start to lose my feelings of unevenness and to feel calm, detached.

The young woman is markedly still, her head slightly bowed over her work. She is sewing, bent, her hair obscures her face and only her hands make a steady rhythmic movement. I have an anxiety about her reddened shiny hair getting caught in the machine. The other machines are quiet. The surfaces of the cream and white washing machines and driers are chipped, scratched and discoloured enamel. They give me a reassuring feeling as my eyes move across the worn surfaces. The young woman appears to be an extension of the sewing machine she sits at, as she’s in a shaded area of the room. Light comes in from the open door opposite me. It cuts a shaft of sunlight across the room, dividing it diagonally, a pleasing symmetry. I feel suspended there with the woman. I know her name. It is Jesse. But for the moment I want to think of her as the woman sewing, an abstract, a shape, which embodies something for me and moves me. There is also something deadening, something of the pall of death in beautiful inanimate objects, or the sight of a pretty woman if I can allow myself to see through the surface. The inanimate coupled with beauty soothes me but also threatens to call me into deadly blissful inertia.

Thus I feel as much of a humming fragile contentment as is humanly possible with the scene in front of me, and I know I could hold it there for as long as I want. And the absorption of the woman, the reassuring ageing of the surfaces, the slightly moving dappled light does start to give me a feeling of deepening comfort as if I were in the most comfortable bed. I’m still in touch with some other part of my mind with all the anxieties surrounding the production that is being pieced together below me. I feel a sickening tension when I allow myself to think about the plays, my plays. I let the queasiness take hold for a while until it gives way and instead I feel my breathing rise and fall in a satisfying way and imagine myself breathing with the woman sewing, both of us caught up in her concentrated stillness, a stillness which seems to flatten the space in front of me into two dimensions.

I am reminded of Max Ernst’s painting Little Machine Constructed by Minimax Dadamax in Person. His paintings of machines are always anthropomorphic. Life is breathed into the dead and vice versa. Things are both dead and alive, as are we. He does not distinguish between the living and the dead. I find myself seeing Jesse through Ernst’s eyes, reorganising her body’s template. I know her to be disquieting, indolent, then conversely light-footed. This knowledge of her opens up the possibility of creating an endless number of pared down forms which would represent and transform these parts of her. This process could go much further than painting, or writing, if, in a live performance, the young woman is stripped to her bare essentials by ageing, her sagging flesh implying weakness and worn sinews, and allowed to utter what is barely explicable in a play.

The striking young woman in front of me, Jesse, is the wardrobe mistress. She defies me by looking extremely healthy. Who the hell is she? Well, she makes costumes for the plays and maintains them. But her presence, kindly lent to me in this moment, has taken on a potential for abstraction and generalisation. This is her domain. This is her room and her place of work, but these specifics no longer matter as I’m seeing a portrait of her, beginning to construct a version of her that barely acknowledges who and what she is but can use a line of this and a stroke of that to suggest an embodied internal life.

Once I have my sketch of Jesse formed in my mind I immediately think of my mother and the contents of her room. I must have inadvertently slipped into her body warmth. She has been dead a long time now. The further the distance, the more I have been able to imagine a warmth unsullied by her actual presence, a warmth that barely existed. She was often the vessel of dark rages. And we fought, God how we battled. Goodness, bury her poor soul. I find myself speaking to her as if she could still hear me somewhere.

I was the focus of your fierce loving. I was the one you saw as yours, unlike my brother, who was seen to be more part of my father. I was to succeed you, but you could not have been more mistaken, because I couldn’t desire what you desired; your wishes were in turns so concrete, undefined and all-encompassing that they terrified me. I felt oppressed and despairing at your controlling presence. On the surface you worshipped me and wanted to mould me, but really you did not worship me, but thought you saw a projection of yourself. Often, once my actual feelings became apparent, you could not even like me. Your deep love was full of contradictions. How was I supposed to make sense of such opposites?

Yet my father could like me. He just accepted me as his boy, a different boy from my brother. He liked his two clever, physically able, good-looking sons, as he saw himself as a man with a reasonable brain and a strong physical body. What else did his sons need? When my father died I felt the fragile structure of myself fracture. I found the nearest pub. Sitting there with a pint, I knew I needed help. I was thankful to have a friend – friends – to take hold of me then.

I abandon this one-way conversation. I don’t like this whining voice, which comes from my mother and is not one that I would like to think as recognisably my own. I’m struck by the thought that George might see me as wanting to dominate him as my mother dominated me, but nothing could be further from the truth. I didn’t want to be fucking with him, I wanted to direct him in the play. I was to be his best guide but he didn’t accept this.

I yearned for my mother, only to be met with her wanting me to be an extension of her. I had to keep myself separate from her emotional avarice. Edna, my first love, felt just as devouring. So I learned to lust and yearn for her in her absence. This could, out of cruel necessity, set the distance needed for me to feel inviolate.My whole life has been a quest to maintain a sense of being free of intrusion. Silent contact is best, so I have cherished my long companionship with my wife. With her it has been possible to be close to a woman and only exchange the minimum necessary. That is real conversation – not endless chattering. It used to be the same for sex; contact that arose out of absence, hence as a young man I used the brothel houses. With women cared for or loved, when the pressure to perform was unavoidable, the whisky would help, or hinder. Perhaps George thought I wanted to take him over like an obsessed lover – nothing could be further from the truth. It’s impossible for me to help George. I cannot o;er any actor help in this situation. The crisis is not big enough to talk of radical steps. We can only keep within the frame of the work.

I needed help once. I was falling apart and couldn’t face my own sufferings, hypersensitive to all kinds of misery and affliction, large and small. I was given enough to help me understand myself and the implication of others’ suffering; that it exists and has to be faced and incorporated into oneself. My friend the psychiatrist helped me by taking me to Bedlam. I shall never forget a young psychotic man, overly attracted to his mother, who reminded me of myself and my own troubles. I was so relieved that the permanent psychotic suffering was not my own, and I learnt that there was a divide between psychological struggle and psychological collapse. The decisive factor at that time for me was to be open to another. It was not without a fight. I gave my shrink a little of my hell. I was angry, insistent in my own superior view, able to show my superior intellect and feel I was at least as clever if not more so than him. I was able to be as ambivalent, ambiguous and as obstructive as possible while also wanting to befriend him. I wanted to show my kind, avuncular man I could understand his analysis as well as him. I had to be alongside him, not just his patient. I could be pretty unpleasant to him and vent my frustration on him. I’d complain about him to my friends. I took his learning for my own purposes. He would have approved: After all, a creative theft is a compliment. My two years of studying the Shrinks and being on the couch, and in a parallel combative relationship with Proust, gave me all the psychological insight I needed for my work. I am proud to say my personality came out unscathed from the encounters with the big psychologists. Jung, whom I came across, also helped point the way: not to lament my physical symptoms and my neuroses but to utilise them while learning to forego habit and the illusion of security.

Mora Grey

This is terrific!

Comment by Dafydd ap Pedr on 27 February, 2017 at 1:56 pm