By Leon Horton

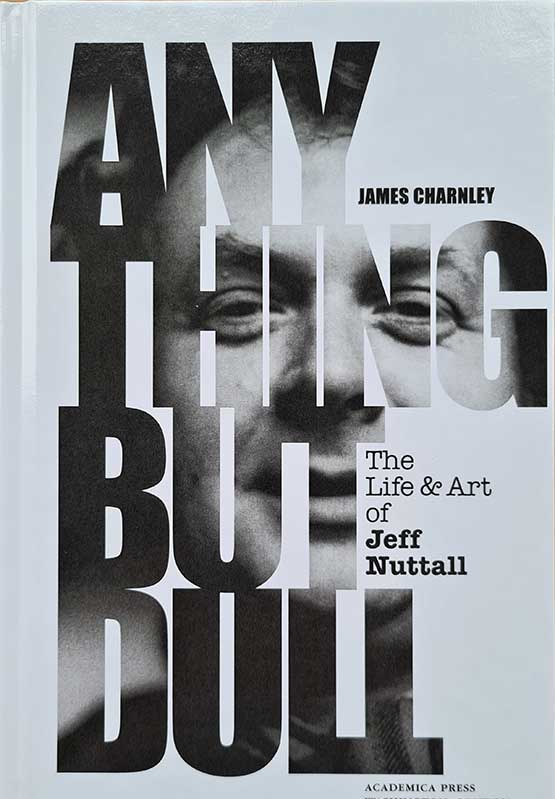

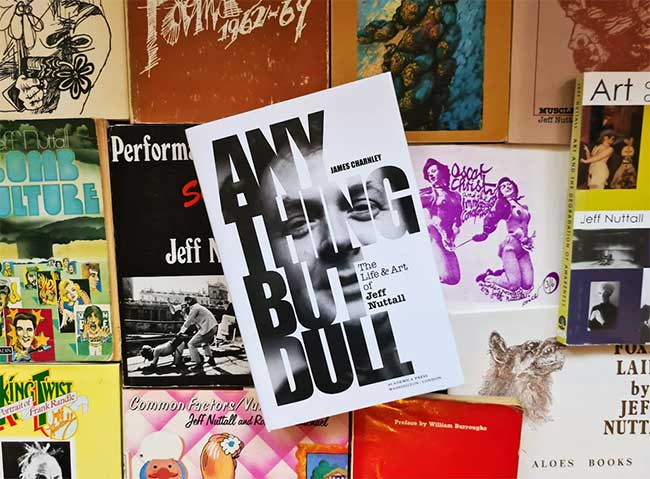

Provocative, uncompromising, disturbing and violently funny, countercultural artist Jeff Nuttall was a great many things – actor, teacher, writer, jazz preacher – to a great many people thanks to his work with My Own Mag, The People Show and Bomb Culture. Over a career spanning more than 40 books and a multitude of mediums, controversy, outrage and calls for his dissolution were never far behind Jeff. To celebrate the life of this extraordinary polymath, Leon Horton talks to James Charnley, author of a compelling new biography, Anything But Dull: the Life & Art of Jeff Nuttall.

James, you studied Fine Art and Art History at Manchester, Chelsea and Leeds polytechnics, but what specifically made you want to write a biography of Jeff Nuttall?

Originally, I was going to do a follow up to Creative License, a book I wrote about the radical art experiment at Leeds College of Art and the Polytechnic. When I started interviewing survivors of the course, I realised that Jeff Nuttall was the story. He had presided over a notorious decade at the Polytechnic and had then gone onto Liverpool where things got even more out of hand. It was hearing how he had burst into tears when talking about his Liverpool experience that drew me into the story. I wanted to know what happened and why and it went on from there.

Anything But Dull is a meticulously researched biography, both scholarly and a page-turner – a fascinating and hugely significant work. You interviewed, I believe, more than eighty people. How long did the book take to research and write?

Three years. The Covid thing didn’t help.

The word ‘polymath’ is bandied a great deal in reference to Nuttall, I’m guilty of it myself, and he certainly had his fingers in a great many pies, but – playing devil’s advocate – we could just as easily describe him as ‘jack of all trades’, couldn’t we?

Good Question. Nuttall spent his life moving in and out of various disciplines and famously told International Times: ‘I paint poems sing sculptures and draw novels.’ I don’t have a problem with this pick ‘n’ mix approach. In many ways it is the most natural thing for a creative person to do and was also part of the avant-garde project at the time. As a fully signed up modernist Nuttall just took things further than most. From the beginning he was not tied down by any particular art form. He began with comic strips, which use text and image together. Jazz was his next and longest lasting passion; while at Art College he studied painting and sculpture and had his first intimations of Performance Art. He was also an activist and saw art as a method of communicating his ideas. He was writing poetry and segued easily into prose to get his message across. In this respect words are more precise than painting and his performances always had a script. So, I think he used the most telling medium for his message. He also brought a visceral intelligence to his writing. William Burroughs said he touched words and that is a highly condensed expression of Nuttall’s style. He gets in there and ruts around without reference to codes or convention, relying on his gut feelings and inspiration.

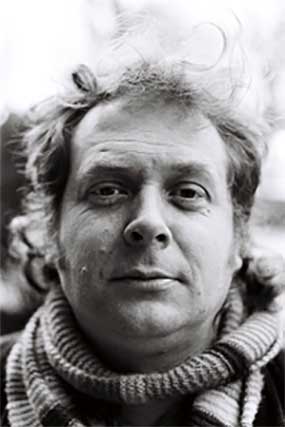

photo by Tony Skipper

Nuttall was born in 1933 in Clitheroe, Lancashire, but grew up in Herefordshire, where his father worked as a school headmaster. You write about traumas in his childhood. Did his formative years define the kind of artist he would strive to be?

I think it did and by his own admission he stated he could never have written a line of poetry without those traumas. Another strong influence from his childhood years was his preference for the rural over the urban environment despite living in major cities for most of his career.

He would become one of the major players of the UK counterculture, which burst into flower – ‘come and drink the dew,’ he said – at the International Poetry Incarnation at the Royal Albert Hall in ’65. But Jeff was way ahead of the curve, wasn’t he? Staging “Happenings” with John Latham in the cellar of Better Books, working with Alexander Trocchi on his ultimately abortive Sigma project…

Jeff saw art as the means to bring about a revolution in human consciousness. He was frustrated by conventional forms of protest and really by the grip of the art establishment on culture. He was right that art could be hugely influential; culture is upstream from politics and the whole of the Sixties can be understood as an artist-led revolution that redefined societal norms. I include poets and most importantly musicians in this.

He was probably best known for My Own Mag: A Super-Absorbant Periodical, which ran for sixteen issues between 1964 and 1967, and Bomb Culture, his love letter / Dear John letter to the ‘alternative’ scene that was mushrooming through the cow shit. That period, that creative outpour, did it overshadow his later work?

I think it did, but in fairness Nuttall made very little attempt to consolidate his reputation post Bomb Culture and by the time he did the wave had passed. Pig, published in 1969, is indulgently modernist and would lose him any followers he might have gained from Bomb Culture, which is far more accessible and of the moment. He wrote over 40 books but most of them were not aimed at a mainstream audience. In truth, he was disillusioned with the direction the counterculture had taken and his subsequent work reflected this. Snipe’s Spinster raked over the ashes of a failed revolution, but it was not until his penultimate book Art and the Degradation of Awareness that he returned to the format and themes of Bomb Culture.

Bomb Culture often sees Nuttall in full elegiac mode, you can sense him typing a sweat when his blood is up, not always entirely accurate in his observations (Dennis Potter described the book as ‘ignorant and yet brilliant’) but far more interesting than prosaic truth. Anything but dull. Was bombast and attitude his MO?

Bombast and attitude is a bit harsh but certainly in full flow Nuttall was hard to oppose. Of course, the price he paid for this was to make enemies and become a big target, most notably with feminists, where he seemed to represent everything they hated about men. In fact, he was very hurt by the treatment he received by radical feminists, who he had once seen as fellow travellers.

Is it fair to describe Nuttall as a transgressive artist? He seems so much more than that…

Nuttall had no respect for authority except his own. By his own judgement he was not being transgressive, rather he was exploring greater freedom of expression where nothing was off limits. His aesthetic was driven by the need to shock and show what had been hidden by conformity. This worked well early on, not so well later – and eventually really was transgressive as the era of political correctness closed in.

I think another factor in his reputation was that Jeff was heterosexual. Gay artists and writers avoid accusations of misogyny. They often like the company of women, but with the sexual element taken out they are seen as harmless. Nuttall, who loved women and was sexually obsessed, became seen as transgressive and sexist; which is not to say that there is no foundation in these criticisms. Laura Gilbert of the People Show had to endure some pretty abusive treatment in the scripts he wrote for her. Essentially Jeff was a provocateur and knew the value of controversy. His lack of caution was calculated.

What, for you, constitutes his finest work?

For all its faults I would still put Bomb Culture at the top of the list. It was an ambitious attempt to explain what was going on to ‘the squares’ – those outside the counterculture where he was a prime mover. Jeff was able to draw on historical precedents and from high and low art and while being personally involved in what he was describing. Bomb Culture is a first-hand account of a defining moment in cultural history. Likewise, his Performance Art Memoir is a valuable record of another history, a time when Performance Art and the People Show arrived and the subsequent direction these pioneers took. I think Nuttall’s Performance Art pieces were some of his best artworks, particularly the spoof lectures with Rose Maguire. Once he felt the inspiration had gone, the very newness and surprise of Performance Art, he lost interest. This was around 1978. He then wrote what for me is one of his finest books: King Twist. King Twist is a delight to read, and his fondness and identification with Frank Randle allows him to write a wonderful biography which is in part autobiographical, a bit like Bomb Culture, but this time it is a drink-fuelled road trip between Blackpool and Scarborough.

I find it strangely comforting that while many of Jeff’s colleagues – Burroughs, Trocchi, etc. – were using drugs, notably speed and heroin, Nuttall, though he dabbled, remained a warm beer man. Was the provocateur old-fashioned in his slippers?

A very important part of Jeff’s psyche was that he was a family man and made sure he was able to support his wife and four children, plus he came from a generation of heroic drinkers and pub culture. He craved the conviviality of pubs so alcohol was his drug of choice and in this way he was old-fashioned. By the Sixties he was already a confirmed drinker and not about to exchange his habits. He needed to get things done and LSD and Heroin did not help in this respect. Methedrine helps, but eventually there is a bill to pick up. Trocchi destroyed his talent and his family with his habit. Jeff was taking notes, did not go down that route, but depended on beer to give him poetic inspiration and the sociable life he enjoyed. His later work also explores the effects of alcoholism, the same territory covered by Malcolm Lowry.

If there is one thing people consistently get wrong about Jeff, what would you say that is?

I would say it is labelling him an enemy of feminism and a misogynist. If he was, it wasn’t intentional and arose from his recognition of the sexual basis of his art. He described his art as a arising from sexual hysteria; his belief that freeing up sexual repressions would build a more caring and honest society got him into trouble when it collided with radical feminists who saw this as sexism. Both could have learned something from the other and it is a pity that the whole thing became so polarised, not to say vicious.

What was he like as a teacher?

I found him extremely perceptive. When he was teaching at Leeds Polytechnic, he was known as a Performance Artist and a poet. I didn’t realise then that he was a painter and a sculptor too, so I was surprised at how much he knew about these ways of working. Not only that, he brought new insights. He commented on a silkscreen image I had come up with via LSD. His comment was: ‘Ah, I see you are working with sympathetic magic.’ I had no idea what he meant by this, so I went away and looked up sympathetic magic and saw how it could relate to image making and learnt a whole new way of understanding the world. So yes, I found him a good teacher, although he has been criticised for setting a bad example. When everything was allowed at Leeds it could go too far, often did. Jeff was held responsible for what he described as ‘a collective pursuit into individual anarchism.’ I would say that was exactly the case at Leeds.

One thing we haven’t discussed, which you cover – warts and all – throughout the book, is Jeff Nuttall as family man. He was no angel, but how do you think he fared when it came to marrying his biological responsibilities to his artistic freedoms?

When I first began researching Jeff Nuttall’s life, I was surprised to discover that by an early age he had a large family – four children by the time he was twenty-eight years old. He married his art school teacher Jane Louch and went to work as a secondary school teacher to provide for his family. So, on one side he was a conventional married man, but on the other he was an artist and activist who in his spare time was trying to start a revolution. He played jazz cornet in protest marches, had his own underground magazine, one of the first, and was mixing with avant-garde bohemian artists who he was trying to organise into a revolutionary movement. Something had to give and his family life suffered. Jane had to suffer his infidelities, and his eldest son Danny was the victim of his temper tantrums. His record here is not good, but when you consider just how much he was taking on by the mid-sixties it is perhaps understandable that he could not live up to the ideal of a family man.

How did Nuttall evolve as an artist?

That’s a big question. One of the major drivers in the evolution of his art was the fear, even the expectation that human life would end in a nuclear Armageddon. In 1962 he destroyed all his paintings, threw away his CND badge and began to make art that addressed the threat of imminent extinction. His art set out to shock and break down the cultural conventions of post war life, much as Dada had done for an earlier war. So he moved out of his private studio into public spaces where he staged ‘happenings’ and set up a Performance Art group, The People Show. His art evolved into one of active engagement designed to bring about a liberated society particularly sexually. The sexual element of his work was a constant and was there in his drawings, sculptures, writing and performance work.

photo by Tony Skipper

By the end of the Sixties, he was disillusioned with the way the revolution had turned into a hippified psychedelic morass. He retreated first to Norwich to write Bomb Culture and then North to teach at art colleges in Bradford and Leeds, where he puts Performance Art on the curriculum. His thinking evolved into a recognition that art comes from the gut as much as the brain. As his friend Timothy Emlyn Jones noted, there was a visceral intelligence that he placed at the centre of his art and identity and was not to be denied or constrained. Of course, such freedom of expression got him into trouble and from the Eighties onwards he was out of step with the art establishment and political correctness. His penultimate book, Art and the Degradation of Awareness was an attack on what he saw as a betrayal of true, inspirational art for commercial gain and shallow principles. Some of the warnings he put out in that book have proved to be highly prescient. It seems to me that artists and writers now are afraid of stepping out of line, it would damage their career. It is time for a new counterculture, perhaps, and time for someone like Nuttall to organise it.

Anything But Dull: the Life and Art of Jeff Nuttall by James Charnley is published by Academia Press and is available through their website or via Amazon.

About the interviewer

Leon Horton is a countercultural writer, interviewer and editor. Published by Beatdom Books, International Times and Beat Scene magazine, his essays and interviews include ‘Hunter S. Thompson: Fear and Loathing in Utero’; ‘The Beaten Generation: Burroughs, Ginsberg, Thompson… and the Battle of Chicago”; ‘Turning the Tables: An Interview with Victor Bockris’; “Charles Bukowski: Only Tough Guys Shit Themselves in Public’; “Where Marble Stood and Fell: Gregory Corso in Greece’; and “Gerald Nicosia: In Praise of Jack Kerouac in the Bleak Inhuman Loneliness”.

I’m pleased to read about Jeff, who I liked very much.

Comment by Dave Holland on 31 December, 2022 at 3:52 amIn the IT archive, are there any of the PDQ cartoons Jeff did? (I think I’ve got the right name.)