Concrete Poetry is sometimes known as Visual Poetry because the shape the words or typed characters make on the page and the visual impact of the poem itself is as important as the text. As a result, the poem communicates via its visual impact as well as its content. ‘Easter Wings’ by George Herbert and ‘The Mouse’s Tail’ by Lewis Carroll are two early examples of the approach. The term Concrete Poetry itself derives from the influence on the movement of the Constructivism and Concrete art that appeared in Brazil in the mid-1950s. Later, during the early to mid-1960s, it became an international phenomenon.

Breaking Lines is a two-part exhibition at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art which focuses first on ‘Futurism and the Origins of Experimental Poetry’ and second on ‘Dom Sylvester Houédard and Concrete Poetry in Post-war Britain’. The Estorick Collection is known internationally for its core of Futurist works, as well as figurative art and sculpture dating from 1890 to the 1950s. Their exhibition programme aims to address artists, movements, and questions in ways that change our understanding of Italian art and culture. As regards this exhibition, the focus is on Futurism as one of the original sources for Experimental Poetry and, therefore, as a precursor to Concrete Poetry.

The two-part exhibition divides neatly into two rooms which, as befits the subject matter, are graphical installations in which images, books, pamphlets, newspapers and videos are cleverly and engagingly displayed. Room 1 has rare original editions of works including Fortunato Depero’s famous ‘bolted book’ Depero futurista, as well as newspapers and journals such as L’Italia futurista, which made a significant contribution to the dissemination of new poetic research and helped establish an international avant-garde network.

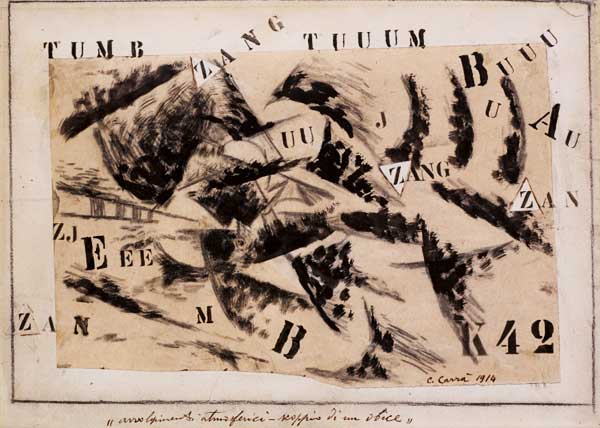

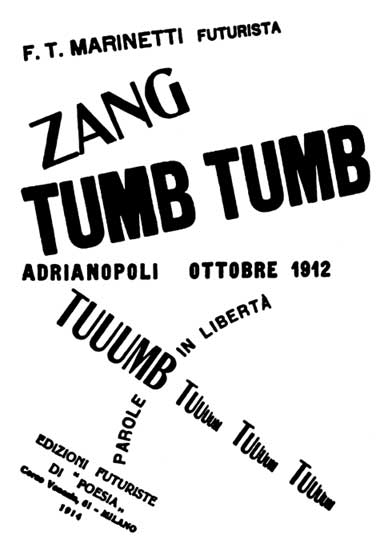

Italian Futurism was founded and led by the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Marinetti’s works moved from Free Verse to parole in libertà or ‘Words in freedom’, a poetic style which did away with syntax and punctuation while also introducing a strong visual dimension. His Zang Tumb Tumb made extensive use of onomatopoeia to evoke the sounds of the modern battlefield and influenced Futurist artists such as Carlo Carrà, who incorporated references to Marinetti’s book into his drawing Atmospheric Swirls – A Bursting Shell. Corrado Govoni’s Self-Portrait also shows this influence, being the first poem-image in his most radical work, Rarefactions and Words in Freedom.

A later Futurist poet Carlo Belloli had the conviction that, in the post-war world, ‘to see will become more necessary than to listen’. Examples are shown from his remarkable volume Texts-Poems for Walls, a collection of 10 works printed on loose, oversized sheets of coarse paper that were gathered together in a folder. Christopher Adams notes, in the newspaper styled catalogue accompanying the exhibition, that: ‘The poet and scholar Mary Ellen Solt has argued that by late 1943, Belloli “was making what would sixteen years later come to be called concrete poetry”, anticipating the ideas of this important international post-war tendency, characterised by a “preoccupation with the reduction of language” and the creation of texts “to be perceived rather than read”.’

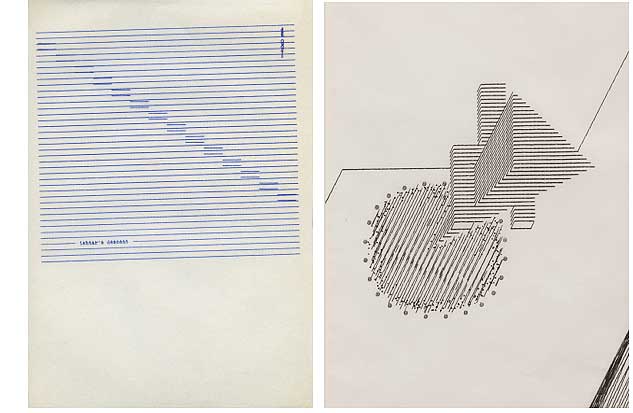

Anticipated in Belloli’s wartime poesia visuale, Room 2 features the work of British Concrete Poets including Dom Sylvester Houédard (aka dsh), Ian Hamilton Finlay, John Furnival, Bob Cobbing and Edwin Morgan. Adams states that their work is ‘grounded in a conviction that the form of a poem – its typographical arrangement and structure – could carry as much meaning as the words of which it was composed, if not more’.

dsh, a Benedictine monk and noted theologian, used a standard Olivetti Lettera 22 typewriter to create ‘typestracts’ ‘consisting of abstract patterns or shapes, employing typewritten characters to generate precise, free-floating geometric forms’. Several of the typestracts shown here include ‘spiritual ladders’, which Nicola Simpson has noted ‘characterise so many of the typestracts’ because, as dsh states in his ecumenical writings, ‘[the] ladder is our life of contemplation’. dsh’s works often relate to apophatic theology, as Adams explains when he writes that a ‘characteristic of his work can be seen as attempts to express the ineffable, or to represent spiritual experiences that were unable to be fully articulated by more conventional means’.

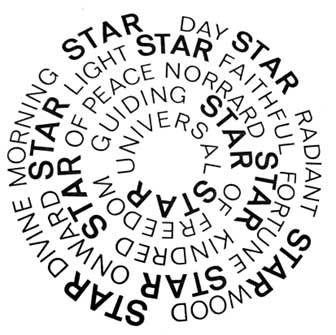

The other Concrete Poets included here place a greater emphasis on semantics than dsh’s enigmatic verbo-visual constructions. Edwin Morgan’s emergent poems feature in a publication Futura 20 and reset texts from the Bible, Burns, Brecht, Rimbaud, Dante, and the Communist Manifesto. John Furnival’s drawing of Devil Trap was the cover image for his artist book Ceolfrith 14. Devil Trap was originally a kinetic sculpture that Furnival, a collaborator with dsh, painted with spiralling words so that curious demons would pursue them down to the trap at the bottom. Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Sea Poppy 2 sets words, which are both the names of fishing boats and also use the word ‘star’, as petals in a radiating sequence forming a flower. The work, which was later reproduced on a postcard for National Poetry Day 2012, brings together his passions for the sea and gardens while pointing to supernatural dimensions.

Exhibitions of Concrete Poetry are not two-a-penny at present, so this exhibition should be embraced simply on that basis. However, as its content and curation are both creative and inspiring, the exhibition can serve as an engaging introduction to Experimental Poetry and, by positing overlaps between Futurist Poetry and Concrete Poetry, also adds to understanding of the movement for those coming with prior knowledge. As curator, Adams compellingly demonstrates to visitors the contention of Futurist scholar Matteo D’Ambrosio when he observed that the pioneering work of Futurists in Experimental Poetry ‘supplied the poetic avant-gardes of the later twentieth century with [fruitful] indications, projects and avenues of research, particularly in the fields of concrete and phonetic or sound poetry’.

.

Jonathan Evens

Breaking Lines, 15 January – 11 May 2025, Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art – https://www.estorickcollection.com/exhibitions/breaking-lines

IMAGES, from top of article:

Carlo Carra, Atmospheric Swirls – A Burning Shell, 1914, Courtesy Estorick Collection

F.T. Marinetti, Zang Tumb Tumb, 1914

(left) Dom Sylvester Houédard, ishtar’s descent, 1971. Courtesy Lisson Gallery

(right) Dom Sylvester Houédard, Untitled, c. 1967 Typed page. Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Sea-Poppy 2, 1968

.