“Only the dead know Brooklyn.”

—Thomas Wolfe

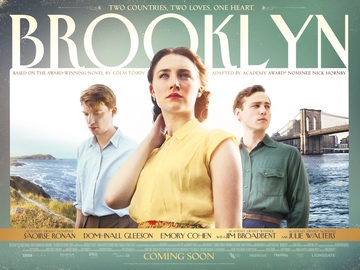

Question: Is anyone responding to the ridiculous stereotyping of Italian-American life in the very successful film, “Brooklyn”? Someone describes the absurdly named hero (“Tony Fiorello”!) as the only Italian-American male who doesn’t think exclusively about his mother and baseball—and then we discover that he is indeed obsessed with baseball. I’m sure that mother isn’t far behind. The actor playing Tony—Emory Cohen—is doing a not entirely convincing imitation of Montgomery Clift, and one constantly thinks how much better Clift would have been in the role. (For one thing, he wouldn’t have smiled so much. No anarchici among these Italians!) The film is lucky to have Saoirse Ronan, whose superb performance saves this slick, mediocre, prejudiced, superficial tear-jerker of a movie from the fate to which it might otherwise have been subject. She is so real that the rest of the film seems real too. In fairness, the Irish elements are better than the Italian—the best of these being a fine sequence in which Irish is sung. And the period detail is excellent if a little too glamorized. (Violet LeVoit describes it as “an amber glow of nostalgia so relentlessly luminous it could set off a Geiger counter.”) But the film depends entirely too much upon its heroine. Too many long, lingering close-ups of her face and her expressive eyes. And faith and begorrah, to misquote Finian’s Rainbow, “If I’m not near the man I love, I love the man I’m near”—but don’t worry, faithfulness and marriage win out. And oh, the music. Oh, the violins. Oh, Barry Fitzgerald. Oh, Life with Luigi.

My remarks opened up a can of worms on Facebook, with some people applauding my stance and others complaining about my criticizing such a “sweet” movie. They were afraid I was trying to take their enjoyment away from them. Well, perhaps I was.

Here are a few excerpts—with my further commentary:

George de Stefano writes: “[Colm] Toibin, who wrote the novel the film is based on, is beloved by the NY Times and the middlebrow lit crit crowd. I find him dull and sexually repressed.”

I answered, “He seems to be a better critic than novelist. He has an interesting essay on Yeats and Lady Gregory in a collection edited by Lavinia Greenlaw, 1914: Goodbye to All That. And his remarks on the Easter, 1916 rebellion are genuinely illuminating. An openly gay man himself, he quotes an explicitly gay poem by the great hero Padraig Pearse and mentions Pearse’s delight in kissing the boys at the school Pearse founded. (One former student says, ‘Well, he didn’t kiss me.’) Toibin was involved in the making of the film, Brooklyn, so he has to bear some of the blame for its sentimentality and mediocrity. He says he grew quite close to Saoirse Ronan. Her character is perhaps a gender-switched version of the repressed gay male of 1950s Ireland. Interesting that she has a mother (and a rather demanding one) and no father on the premises—and the true love of her life seems to have been her sister, not her boyfriend. Same sex relationship trumps heterosexuality.”

Ed Coletti remarked, “I also did not like the movie and am pleased with your review, Jack! I was less offended by the Italian-American portrayal than by the facile and predictable device of the witchy shopkeeper in Ireland as the sole reason the ditzy young woman returns to America and her true love.

At times I have felt bewildered by the adulation this cliché of a film has received.”

I answered, “People like a film which lets them fall asleep in a pleasant haze of sentimentality. That the film has disturbing subtexts doesn’t have to be noticed. As for returning: it’s a movie, she’s married, she has to go back. But I think her true love is her sister.”

Another person (female) complained, “She was struggling with being in love with two attractive men; maybe that is something hard for guys to get.”

I answered,

“Not so hard to get. You’ve seen precisely that situation in thousands of movies (books as well). It’s a projection of the male notion of the nuclear family (father-son-mother) and it’s the basis of zillions of stories. The Oedipal triangle (father-son-mother) gets represented as two men and a woman. Both of the men are in love with the woman; the woman is in love with both of the men. But she has to choose. It’s not ‘hard for guys to get’: we’ve been ‘getting’ it in so many films it’s impossible to keep count. It’s a sort of ‘universal’ appeal. For the men, it’s the fun of fighting over the woman; for the women, it’s the fun of having two lovers. Try The Bishop’s Wife, try the first Star Wars, try Red River, try any number of popular films. It’s constantly there; it’s a cliché. The difference here is that we don’t SEE the men fighting each other: they’re in two different countries, unaware of each other. The film is in that sense “feminized”—which in this case means written by a gay man, a man who doesn’t emphasize the struggle between the two “contenders” because that was not his primary struggle. Nonetheless, he asserts the cliché—he is writing for an audience that expects it—and remolds it slightly to fit his sensibility. As I suggested above, the film clearly suggests that the woman is rather cool towards both of her men (‘He’s nice,’ ‘He has beautiful eyes,’ ‘He’s a gentleman’): where she really feels something is when her sister dies. I think there is a deliberate suggestion that she loves her sister more than she loves either of the men. Again, the film was written by a gay man. A same sex relationship trumps the heterosexual one.”

She answered,

“Actually the screen play is by Nick Hornby; don’t know if he is gay or not. I took the play at face value, as entertainment and don’t read all that you see into it. I found it moving and enjoyable; guess I’m a sentimental sap.”

I answered,

“Toibin was very involved with the film and, as he says in an interview, became quite close to Saoirse Ronan. The film follows the novel faithfully—so it isn’t the self expression of Nick Hornby. I don’t know whether Hornby is gay or not either. I took the film at face value too. What I am describing is its face value. The film is familiar territory, like many other films, and its resemblance to them allows it to disguise some of its elements—allows the audience not to notice certain things. This is an ancient technique of films—allowing the members of the audience to forget/ignore the very things the film has put before them. After all, it’s just ‘entertainment.’ This occurs in practically every Alfred Hitchcock film. It’s exactly what Bertolt Brecht was AGAINST. He wanted the audience to remember.

*

Domhnall Gleeson, who plays the Irish love interest in Brooklyn, appears in another recent film, the sci/fi Ex Machina. Once again, the plot centers in two men and a woman. (It’s often the case, as here, that one of the men is blond, the other is dark-haired; one of the men is older—“father”—one of the men is younger—“son.”) The variation in this film is that the woman is a robot (“AI”—Artificial Intelligence) and, instead of choosing one of the men, she murders both of them in her quest to escape. If fear of a woman loving someone more than a man (another woman) is at the center of Brooklyn, fear of women getting out of control is at the center of this film. But the starting point of both films is the Oedipal situation: the assumption that there are really only three people in the world; two of them are men, one of them is a woman.

Jack Foley