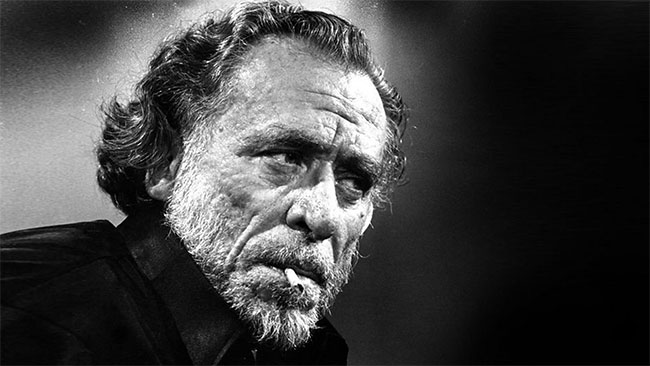

Charles Bukowski, like most writers, was never happier than when he was alone at the typewriter; beer-in-hand, glugging into the night, hiding in plain language. But writers, especially poets, can rarely afford to let their work speak for itself. Dragged from their caves into the tyranny of the light, they are often pushed into the horror of public readings – if only to shore up their pathetic earnings. And Bukowski was no exception.

Of course he resisted. “When you leave your typewriter you leave your machine gun and the rats come pouring through,” he wrote in Notes of a Dirty Old Man. “When some of my few friends ask, ‘why don’t you give poetry readings, Bukowski?’ they simply do not understand why I say ‘no.’” He kept on resisting, spurning offers even when the money was more than he could make in a month. “The readings I don’t like,” his alter-ego hero Henry Chinaski says in the short story “Would You Suggest Writing as a Career?” in Tales of Ordinary Madness. “They’re stupid. Like digging a ditch.”

With the amount of recorded Bukowski readings available, it is sometimes difficult to appreciate his terror of such events (especially on those rare occasions where he sounds relatively sober, relaxed and in a good mood – but equally so where those recordings show him drunk and belligerent and attacking the audience; sometimes, quite rightly). Contrary to his public image, Bukowski was a shy man, not effusive by any means, and public readings filled him with the kind of fear that makes your eyes bleed. As Bukowski himself clearly illustrated in “the poetry reading”, first published by the California Librarian in October 1970, and later in the collection Mockingbird Wish Me Luck (1972):

at high noon

at a small college near the beach

sober

the sweat running down my arms

a spot of sweat on the table

I flatten it with my finger

blood money blood money

my god they must think I love this like the others

but it’s for bread and beer and rent

blood money

I’m tense lousy feel bad

poor people I’m failing I’m failing

The poem continues, the poet suffering the indignity of a woman walking out on the performance, trembling as he struggles to read “a dirty poem” – and swearing, “I quit, that’s it, I’m finished.” Back in his room, with only whiskey and beer for company, the poet laments:

this then

will be my destiny:

scrabbling for pennies in dark tiny halls

reading poems I have long since become tired

of.

Bolstered by making numerous poetry recordings – many of which have since been lost – for various friends, record labels and radio stations, Bukowski finally relented and gave what is widely regarded as his first public readings on December 19/20 in 1969 at the Bridge bookstore just off the Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles. His nerves were shot, as he confided with friends. “What am I going to do? I just don’t know how to do this.”

The venue was packed with more than a hundred people, which did little to assuage the poet’s anxiety. According to Howard Sounes in his biography Locked in the Arms of a Crazy Life:

Bukowski was lit by a spotlight, sitting in an easy chair on stage with the galley proofs of The Days Run Away Like Wild Horses Over the Hills. “He is sitting there like a grandfather,” remembers Steve Richmond, one of many friends who came to watch. “Nice scene – everybody so close to him. It was a magic thing.”

Although extremely nervous, he read fluently, choosing his best work, and the audience stayed with him. As his confidence grew he smiled, drank beer from a bottle and even extemporized a poem, “Carter to resign?” from an article in a daily newspaper. Richmond notes how different the evening was compared with the rambunctious readings Bukowski gave later in his career, when poet and audience traded insults. “It was so prefect, so right, everybody believed in him and was feeling for him, not in a pitying way, and feeling his pain when there was pain.

The success of the Bridge readings did little to improve Bukowski’s distaste for public appearances, but he clearly recognized their necessity. After finally quitting his job at the post office to write full-time, living on a $100 a month stipend from his publisher John Martin, he needed another source of income. Over the next decade, he gave dozens of readings, steadily upping his fee, at numerous universities, colleges and arts centres. In 1973, he even summoned the courage to perform a staged reading of girlfriend Linda King’s one act play, Only a Tenant, at the Pasadena Museum of the Arts.

The public image of a writer is a double-edged sword – what first makes them seem so fresh, so gutsy, so relevant, can (almost overnight) become a monstrous bugbear impossible to live up to. Witness Hunter S. Thompson. Thanks to his prolific output, Bukowski’s writing was slowly getting recognized from coast to coast, but it was his reputation on the live circuit that preceded him. Combating the terror of such events with heavy drinking to steady his nerves, Bukowski’s readings were becoming much anticipated events – but, as often as not, the crowds came not for the poetry but the spectacle.

e Ferlinghetti, who would find himself on the sharper end of Bukowski’s ill behaviour. In Locked in the Arms of a Crazy Life, Howard Sounes detailed one of Bukowski’s most infamous public readings from 1972, organized in San Francisco by Ferlinghetti and City Lights Books:

Bukowski bristled at the idea of being cast as a performing clown – but for reasons unknown he continued to endure – even play up to – the crude expectations of his audiences. If it was dirty poems, sex and drinking they wanted, then that was what they would get. “You disgusting creatures,” he told the braying crowd at Baudelaire’s nightclub in Santa Barbara. “You make me sick.” At a benefit reading in Santa Cruz, he grabbed Allen Ginsberg in a headlock and yelled, “Go ahead, Allen! Tell the folks you’ve been writing bullshit for 20 years. Tell ’em you haven’t written a decent poem since HOWL.”

Ginsberg took it all in good humour, but it would be another Beat stalwart, Lawrenc

Eight hundred people paid to get into the gymnasium on Telegraph Hill, eager to see the author of Life in a Texas Whorehouse and the other outrageous, apparently autobiographical stories. The idea of appearing before them terrified Bukowski. Although he looked intimidating, he was chronically shy and hated himself for hustling his ass in the hometown of the beat writers, a group he neither liked nor considered himself part of.

He’d been drinking all day to get his courage up, on the morning flight from Los Angeles, in the Italian restaurant where he and Linda King had lunch, and behind the curtain while waiting for his cue to go on. His face was grey with fear, and he vomited twice.

“You know it’s easier working in a factory,” Bukowski told Taylor Hackford, who was filming the event for his 1973 documentary Bukowski. “Listen,” Bukowski told the crowd, “some of these poems are serious and I have to apologize because I know some crowds don’t like serious poems, but I’m gonna give you some now and again to show I’m not a beer-drinking machine.” He opened with “the rat”, a poem about his hated father.

As the evening progressed, Bukowski got drunker and meaner. “One more beer, I’ll take you all,” he cackled, whipping up the audience. “You want poems?” he snarled. “Beg me.” The drunker he got, the more the audience bayed for blood. “Fuck you, man!” someone shouted. “It ended up with them throwing bottles,” Ferlinghetti told Sounes. At an after-show party at Ferlinghetti’s apartment in North Beach, Bukowski was so drunk he started a fight with girlfriend Linda King and smashed the place up. Ferlinghetti was appalled. “Didn’t I warn you?” said the poet Harold Norse, who knew Bukowski of old.

With his growing reputation as the “wildman of poetry” it’s a wonder Bukowski was asked to read at all, but the offers kept coming, the money was good, and the events more often than not were sell-outs – in more ways than one. Bukowski was in danger of becoming a caricature of himself, but the more he insulted the audiences and his hosts, the more they lapped it up, the more he despised them. “So this is how this bullshit works,” says Henry Chinaski in “Would You Suggest Writing as a Career” after a reading based on Bukowski’s bad experience at Bellevue Community College in Seattle.

In May 1978, Bukowski embarked on a trip to Europe with girlfriend Linda Lee and his friend the photographer Michael Montfort. Montfort wanted Bukowski to write the text for a photographic journal of the trip, which became Shakespeare Never Did This: a raucous travelogue that saw Bukowski and Lee accused of smoking dope on the plane over to Paris. He visited his uncle in Andernach (Bukowski’s birthplace) and took part in a television interview on the French discussion programme Apostrophes, where he called the host a “fucking son of a fucking bitch asshole” as the show went out live.

Halfway through the tour, May 18, Bukowski arrived in Hamburg to give a reading at The Marktahalle. Bukowski, nervous as hell, was about to discover just how popular he was in Germany, as the twelve-hundred capacity venue was sold out, with three hundred turned away at the door. As Bukowski recalled in Shakespeare Never Did This:

There was that audience, all those bodies were in there to see me, to hear me. They expected the magic action, the miracle. I felt weak. I wished I were at a race track or sitting at home drinking and listening to the radio or feeding my cat, doing anything, sleeping, filling my car with gas, even seeing my dentist. I held Linda Lee’s hand, about frightened. The chips were down.

“Carl, I said. He was standing near. “Carl, I need a drink, now.”

Good old Carl knew. Right behind and above us was a little bar. Carl ordered a few drinks through the railing.

Carl Weissner, Bukowski’s friend and German translator, was equally amazed at the rock star reception Bukowski received as he pushed his way to the stage. “We had no idea so many people would turn up… people from Sweden and Denmark and Holland and Austria.” The crowd chanted and offered Bukowski bottles of wine as he pushed forward:

The crowd was massive, animal-like, waiting.

The drink helped. Even holding the drink helped. I stood there and finished it off. Then we pushed down between bodies trying to reach the stage. It was slow going. We simply had to push between and over bodies. They were shoulder to shoulder, ass to ass. I usually vomited before each of my readings; now I couldn’t do that… Sometimes I was recognized and a hand would reach out toward me and the hand would be holding a bottle. I took a drink from each bottle as I pushed downward.

As I got closer to the stage the crowd began to recognize me. “Bukowski! Bukowski!” I was beginning to believe I was Bukowski. I had to do it. As I hit the wood I felt something run through me. My fear left. I sat down, reached into the cooler and uncorked a bottle of that good German wine. I lit a bidi. I tasted the wine, pulled my poems and books out of the satchel. I was calm at last. I had done it 80 times before. It was all right. I found the mike.

“Hello,” I said. “It’s good to back.”

Unlike so many of his previous performances, the audience treated Bukowski with the reverence he deserved, laughing at his jokes, captivated by the more serious poems. There were some hecklers, mostly bikers and feminists, but the poet dealt with them in good humour.

The Hamburg crowd was strange. When I read them a laughter-poem they laughed but when I read them a serious poem they applauded strongly. A different culture indeed. Perhaps it was losing two major wars in succession, perhaps it was having their cities bombed flat like that, their parents’ cities. I didn’t know. My poems were not intellectual but some of them were serious and mad. It was really the first time, for me, that the crowd had understood them. It sobered me so I had to drink more.

On October 12, 1979, Bukowski gave what would be his final reading outside the US at the Viking Inn in Vancouver, which was filmed and released as There’s Gonna Be a God Damn Riot in Here. “You guys paid six dollars to get in here,” Bukowski joked with the audience, “and you think I’m a fool.” The audience laughed, and Bukowski, sounding relaxed and in good form, launched into “The Secret of my Endurance”. It was his endurance put to the test, however, as once again the event descended into a vicious dialogue, with Bukowski angrily announcing, “I’ll never do another of these readings.”

Two months later, on November 9, Bukowski wrote a letter to Carl Weissner, the friend who had done so much to establish his reputation as a writer in Germany, the country of his birth:

Back from Canada reading. Took Linda. Have video tapes of the thing in color, runs about two hours. Saw it a couple nights back. Not bad. Much fighting with the audience. New poems. Dirty stuff and the other kind. Drank before the reading and 3 bottles of red wine during but read the poems out. Dumb party afterwards. I fell down several times while dancing… Hell of a trip… Nice Canadian people who set up reading, though. Not poet types at all. All in all, a good show.

By the nineteen eighties, Bukowski’s royalties from his published writing were such that he no longer needed to suffer the indignity of live performances, and on March 31, 1980, he gave his last ever public reading (charging $1000) at the Sweetwater, Redondo Beach, California. Released as an LP and CD titled Hostage in 1985 and 1994 respectively, then as a DVD in 2008 titled The Last Straw, the evening found Bukowski in fine form.

“Tonight is going to be a very dignified reading,” he announced. “I will not rejoin, or have rejoinders with the audience. I shall read you dignified poetry in a dignified way.” The audience laughed and were appreciative during such poems as “I Am a Reasonable Man” and “Eating the Father” – and Bukowski, clearly enjoying himself, regaled them with an ad-libbed “Performance Art with the Audience”: “You guys are a real rowdy gang,” he joked. “Goddamn, I don’t know how I’m gonna handle you.” He left them wanting more.

Writing is a prison sentence where you get time off for bad behaviour. For Bukowski, a man who enjoyed the confines of four walls, it protected him from the outside world. He never lost his fear of public performances, but he remained in awe of them. As he wrote in “Would You Consider Writing as a Career?”: “The applause surprised me. It was heavy and it kept on. It was embarrassing. The poems weren’t that good. They were applauding for something else. The fact that I’d made it through, I suppose…”

By Leon Horton

About the Author

Leon Horton is a countercultural writer and editor. Described as “not quite what we’re looking for,” his writing is published by Beatdom Books, International Times, Beat Scene, Newington Blue Press, Empty Mirror, Erotic Review and Literary Heist. He is the curator of the chapbook Gregory Corso – 10 Times a Poet (available soon from Newington Blue Press) and is also a member of the European Beat Studies Network.