…Unless soul clap its hands and sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress.

I met Doc Humes in the spring of 1970, when I was staying in my friend Will Darby’s apartment, which overlooked the Columbia University campus on 114th Street in New York. I’d known Will since Andover, where he was, I think, the first person to sell pot on that campus. He continued selling reefer at Columbia, along with acid and hashish. Will’s living room worked as his storefront, and there were always lots of interesting people from all over New York dropping in to buy the kilos of marijuana and slabs of hash that he displayed on the coffee table, or the tabs of windowpane acid in the frig. Although he sometimes sold cocaine too, he stayed away from heroin completely.

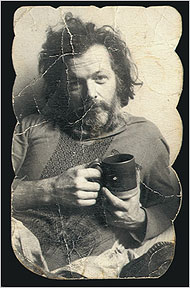

Doc Humes, the founder of the Paris Review and author of the novels Underground City and Men Die, had turned up on the campus at Columbia that spring, and made a big stir by handing out several thousand dollars–in hundred dollar bills–from his inheritance to astonished random passersby. There was an article in the New York Times about it, which provoked a letter from George Plimpton to the Columbia Spectator asking the students to give the money back, as Doc was off his trolley.

Was he? That was subject to debate. He certainly looked like a bum, with his scraggly grey beard, ripped khaki pants, and worn out shoes; but he was a counter-intuitive bum who gave money away instead of begging it. This naturally drew people toward him, to hear his fascinating, mesmerizing, but ultimately exhausting monologues about the virtues of marijuana, the diabolical exploits of the CIA, the subtle forms of the astral world, and the quest for human happiness. He’d follow one or another student home, flowing on the stream of his strange erudition, and wind up crashing on their couch for as long as they could handle it, which was normally two or three days.

Will’s brother Peter brought Doc over one day to get him out of his own house, and when Doc saw all that reefer on the coffee table he turned to Will with a flattering, beatific smile. One of the couches faced a window that looked out over Low Library on the Columbia campus, a masterpiece by Stanford White. Doc sat down on the couch, looked out the window, and with Will’s permission rolled one of his trademark, thin-as-pencil-lead joints, in which the weight of the pot hardly equaled that of the paper. As we smoked the first of dozens if not hundreds of joints with him, he made it plain that guys like Will were man’s best shot at earthly salvation.

For the next few months you could generally find Doc right there, any time of the night or day, lying on the couch, looking out the window, smoking one of his skinny joints and rapping away. You could hear him talking when you came in the apartment, and if you wandered down the hall and into the living room, he’d turn his head in your direction and continue whatever he’d been saying as if he’d been talking to you all along. This was always disconcerting, as the bugging systems of the CIA played a large role in these ruminations and he seemed to spend most of his time arguing with them about the electrodes they’d implanted in his teeth and brain to monitor his activities.

Although I saw him every day for months, I often wondered if he recognized me. It was as though the formlessness of whatever being he addressed when the room was empty was extended to any real person who happened to come in. He believed that certain spirits inhabited clouds, and there was a nice view of the northern sky from his window. I sometimes wondered if his interminable monologues were addressed as much to those spirit clouds as to his own hallucinations in thin air. Doc seemed to see everything in equally cloud-like form, which sharpened up the unseen world considerably for him, but made the conventional one rather cloudy.

You couldn’t really converse with him; his mind deflected anything you said, and the most you could hope for was to steer him in a more interesting direction, toward Lord Buckley, Norman Mailer, Ornette Coleman, or the Paris Review, for example. He’d receive such overtures shrewdly; he might give you a sentence or two at a time on such subjects, in the course of an hour’s disquisition on the microchips the government had implanted in his teeth. He had more compelling things to do than reminisce: Doc was trying to confound the new world order–which was literally implanted in his body by malevolent government powers–by the force of his own free will and his fierce yearning for utopia. His running analysis of the ascending order of tyranny and the opposing one of native virtue was what his fog bound thoughts were all about.

Although Doc almost always seemed crazy when he talked, there was a fair amount of sanity in his actions. Some of the guys who hung out at Will’s were black actors like Tony Fallon and Carl Lee, and musicians like Monte Ellison. All of them were using heroin–I still remember the shock when I first saw them tying up in the living room–and Doc challenged the establishment’s laissez-fair attitude toward scag as soon as he arrived, by letting them know that no one but a government stooge would shoot the stuff. Since stooging for the CIA was the last thing on their minds when they came up to Will’s to get off, the theory was annoying. Fallon in particular would sometimes get so mad that he’d throw Doc out.

“Out, Doc, out!” he’d order in a booming baritone that shook the timbers in the ceiling; and the next thing you knew, Doc would quietly, meekly, head for the door. Still, Doc got Monte to lie in a tub of freezing water one time, rubbing his shoulders and feeding him a steady stream of thin reefers for as long as Monte could stand the cold, by way of an addiction cure. It didn’t work, though: a few weeks later Monte stole the TV set from Will’s bedroom to get himself a fix; and even though he came by a day or two later to apologize and confess, Will wouldn’t let him hang out there again until he replaced the TV. I’m not sure he ever did.

I had a motorcycle then to get around town on, and it turned out that Doc loved to ride around as much as I did. We’d go out around midnight, after the traffic died down, and just ride around for fun, stopping to talk to some of the famous street characters of the day, like Moondog, the blind composer and poet, who dressed up in a Viking costume with helmet and horns, and stood at the corner of 54th and 6th from midnight to dawn almost every night when the weather was fair. It was the last place you’d expect to see a blind Viking warrior, which must have been the point. The most I could manage in his presence was something like “Hi, Moondog,” to which he’d nod without speaking, or say something like “How’dya do?” But Doc was able to draw him out, and they’d have a real conversation, notably different from the monologues Doc had with everyone else. Raw youth that I was, I couldn’t understand a word of it.

There was a great jazz musician named Sun Ra who used to play with his ‘Solar Arkestra’ every Monday night for at least ten years at Slug’s, a comfortable, cavernous club on 3rd between C and D with fish nets on the ceiling. The Arkestra consisted of Sun Ra on keyboards; a percussion section of two drum kits and two or three congas, to which Monte belonged; about four saxaphones; four trombones; a couple of trumpets; two bass players; and whatever odd percussionists that happened to come by. They began the set at 10 pm or so, and played one continuous song for the next four hours, until closing time at 2 am. Everyone in the Arkestra wore capes of gaudy, laminated metallic foil, and Sun Ra had a crown of the same material for himself. Since the band never stopped, the various sections would take breaks on their own from time to time; and sometimes Sun Ra, playing a tambourine, would lead all the brass players off the stage and right into the audience, where they’d play in our faces as we sat at the tables.

One night Doc, Pete and I were watching one of those break-outs when Sun Ra come toward us, thumping his tambourine. Doc yelled something up to his ear, and whatever he said, it made Sun Ra stop in his tracks and say something back. Doc stood up and they talked for a bit, soon becoming so engrossed in the topic that they both sat down. So far as I could tell, they were talking about the evolution of the solar system, with particular reference to whether the planets had all spun out from the Sun, which was Sun Ra’s point of view; or whether some of them had also spun out from Jupiter in the direction of the Sun, which was Doc’s theory, for which he offered the collided planets of the Asteroid belt as evidence. This tantalizing fallacy was too much for Sun Ra to abide; he tried to correct the lapses in physics, logic and judgment that produced it, while Doc worked just as hard to help Sun Ra see that his conservative approach could never account for all the phenomena. It was the kind of passionate exchange that could have gone all night, but had to be cut short when the break was over, and Sun Ra went back on stage to lead the Arkestra.

I didn’t knew much about Doc during the time that he stayed at Will’s; I only learned by inference that he had been Norman Mailer’s campaign manager when he ran for Mayor of New York, or that he’d brought Lord Buckley to town for what was planned to be his East Coast comeback tour, but ended up his Last Hurrah instead. I found out that he’d been married when I came home one day to hear Doc haranguing George Plimpton on the kitchen phone. It turned out that he’d been wandering around Lincoln Center that day when he caught sight of his former wife, getting into a limousine with her new husband, Nelson Aldrich. Something must have snapped. He kicked the door a few times, and then started to break a window with a paving stone before the police came in and hauled him away to the station. It always seemed to be Plimpton who took care of problems like that.

But Doc also had a talent for solving problems. One day he and Pete were crossing a street downtown in the Village when they heard screaming ahead of them. A man had taken his wife’s hair in his hands, and was swinging her in circles, brandishing a knife and screaming that he was going to kill her. Everyone was trying to get out of his way, but Doc bounded through the traffic, grabbed the woman in his arms, cracked a stupid joke, and somehow left both of them laughing a short time later.

One night when just Will, Doc, and I were home, someone knocked on the door and in walked two big white guys in trenchcoats, one of whom flashed a badge and introduced himself as Don Merked, narcotics agent. They came down the hall and into the living room, where Doc was lying on the couch, muttering away with a reefer in his hand. When they entered the room he just turned his head as usual and continued rapping as if they’d been there all along. There were two keys of pot, one of them open, lying on the coffee table next to a slab of hash.

“What’s all this?”, said Merked to Will, while Doc rambled on about electrodes and the CIA. “What else you got?”

“That’s it…,” Will started to say, but Merked interrupted.

“What’s in the fridge?” he said.

Doc snapped out of his monologue at that, and followed them into the kitchen, quietly taking in the scene. The two men rummaged around in the refrigerator until they came up with an envelope full of acid.

“Looka here”, said Merked, as he counted the hits. “Where’s the rest of it?”

“That’s all of it,” said Will, looking down at the floor. Then things took an ominous turn.

“Don’t give me that shit. We’ve been watching this place for weeks. You got junkies coming in and out all day.”

They thought he was dealing heroin.

“I don’t deal scag…,” Will said.

“You got half of Harlem in this fuckin’ place!”

It was true; for a student apartment there were a lot of non-collegiate blacks. Suddenly Doc piped in.

“We got a treatment center, man.”

That shut everyone up completely.

“You gotta what?”

“Addiction treatment center. These guys come up, they’re strung out on scag, and we try to help ‘em out.”

There was nothing Will could do but go along, and after all, it was true. “Yeah,” he said, as Merked and the other cop looked over to get his take.

“You give these guys some pot to calm ‘em down, and a massage to cool ‘em out, and you put ‘em in a tub of cold water and you drive it out of their system.”

“No shit,” said Merked. He looked back and forth between the student pot dealer and the aging beatnik hippie. Then he burst into laughter, laughing so hard that he doubled over.

“A treatment center!” His partner didn’t think it was funny, though.

“That’s right,” said Doc, calmly. “It works, too.”

Merked thought about it for a minute.

“Look,” he said to Will, “we thought you were dealing heroin.”

“I’ve never dealt heroin,” Will said, which was true.

“OK. But if I find out you’re lying, if I find out you are a dealer, I’m gonna break down your door at four in the morning, and I’m going bring along the scag I’m gonna bust you for.”

“OK,” said Will.

“I don’t care about this,” Merked said, giving Will his acid tabs. “I only care about narcotics.”

“That’s cool,” said Doc.

Will walked them to the door, where Merked gave him a card in case he ever needed anything. I could hear him say thanks, and then bolt the door. Back in the living room, Doc was grinning from ear to ear. He lit another reefer, lay down on the couch, and we all had a good laugh. An hour later he was mumbling again.

After three or four months, Will finally kicked Doc out. He tended to freak out our girlfriends, because he was so strange, and it was exhausting to to deal with his paranoid rap. I never thought Will begrudged him the pot he smoked, because the joints were so thin. Shortly afterwards Will told me that I’d have to find another place as well, and after a week or two I found a ground floor, rear apartment on 10th between B and C for $70 a month. I was trying to make a career as an actor, and went around town auditioning for plays that sounded interesting. I wouldn’t normally go out of town, but a group in Princeton was organizing a production of Waiting for Godot that I figured I should try for, and when I mentioned it to Pete he said he’d heard that Doc was in Princeton, too.

Apparently Doc had gone to Princeton, where he grew up, to get some money from a bank account he had there. But he arrived at the bank past closing time, and after fuming for an hour or so he decided to take matters into his own hands by breaking through the picture window with a brick. They caught him crawling into the bank through the broken glass and ran him in, and Plimpton had to bail him out again. A trial date had been set, and in the meantime Doc checked into the Naussau Inn to wait. I decided I might as well look him up while I was in town.

I called ahead the night before, and Doc said it was fine to come visit after the audition, although as usual I wasn’t sure that he knew who I was. I arrived about eleven o’clock in the morning, asked at the front desk for Harold Humes, and they sent me to his room on the second floor. The man who opened the door was certainly Doc Humes, but he was hardly the same man whom I’d known before: he was all cleaned up to begin with; he’d trimmed his beard, cut his hair and fingernails; and he was sporting a brand new set of clothes, including a regimental tie and a Tartan plaid sport coat.

“Hello, there, laddie!”, he boomed in deep Scottish brogue, as he opened the door to the room. I sat on the only chair, while he perched regally back at the head of the bed, crossing his wing tips at the ankles. “And how would ya be getting on?”

“I’m doing fine, thanks,” I said. “I was sorry to hear about your legal trouble.”

“And will ya be a player in the theatre, now?”

“I hope so. I’ve got a shot at Waiting for Godot.”

“Now there’s a morbid Irishman, for ya!” He bounded back up on his feet at this, and I had to respond in kind. We were a little bit closer than I would have wanted. His eyes seemed clearer than before, and they retained the shrewd intelligence that was Doc’s most prominent feature; but I still had that uncanny feeling that he didn’t really recognize me.

“Doc, why are you speaking in that accent?”

“An excellent question, laddie”, he said confidingly, slightly thickening the brogue, “I’m going to tell you the story… Because it’s about the law, laddie, the origins of the law, it is. Because the law was invented in Scotland, ya know, by Scotsmen, too, and the rhythm of the Scottish tongue suffuses every page of every law ‘twas every passed in any corner of the globe… And when a man goes to read the law, and study the law, those rhythms of the Scottish tongue become the untold bedrock of his soul… And laddie, me boy, there’s narry a judge in all the world who doesn’t hark kindly to the sound of a Scottish brogue.”

That was the last time I saw Doc. I never found out how his court case went, but I wouldn’t be surprised to hear that the Scottish strategy worked. He had a knack for those kind of things. I did hear about him one last time, though. He apparently stayed in Princeton for a while, and then moved on to Bennington, Vermont, where my younger brother was going to school. One day, some three years after the Naussau Inn, John called me on the phone.

“Hey, Rick, do you remember telling me about this guy named Doc, who lived at Will’s apartment, who was kind of a hippie?”

“ Sure,” I said. “Doc Humes.”

“Uh huh. And didn’t you say that he used to roll joints that were thin as pencil leads?”

“Yeah, that’s right. Why?”

“Well, he’s smoking one of those joints in my living room right now.”

We had a good laugh over that one. One of Doc’s daughters was at Bennington as well, and Doc had come up to see her, and then somehow landed in my brother’s house. He stayed for a few days, but that was all they could take.

How could anyone be so lucky as to know a man like Doc? The truth was that Doc was available to anyone he met, at least during the time that I knew him. He’d literally follow you home, if you let him, although it helped if you also had an ounce or two of pot. He drove most people crazy right away, and they had to get rid of him no matter what. But the scene at Will’s was crazy enough that Doc kind of fit in.

One of his daughters, Immy Humes, made a beautiful film about him, that proved through freedom of information papers that the FBI and CIA were keeping tabs on Doc–pretty close tabs, really–through all the years when he was obsessed with the CIA. Which suggests that his rants about the malevolent rise of the national security state through the transistors in his brain might well have had some basis in reality. It might have been electrodes as he claimed, or perhaps they just gave him some bad acid, as they did to so many others. Or maybe Doc was reading their minds, instead of the other way around. It’s one of those cloudy questions that can only be answered poetically, if at all.

.

Richard Squires