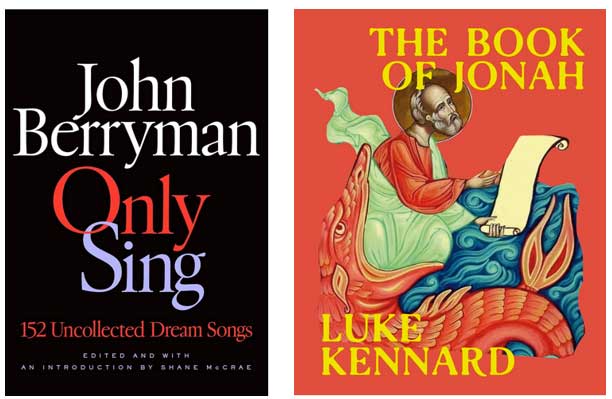

Only Sing: 152 Uncollected Dream Songs, John Berryman (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

The Book of Jonah, Luke Kennard (Picador)

John Berryman’s The Dream Songs are 18 line poem dispatches from a private hell, an interior conversation and a kind of madness that facilitates self-diagnosis and a disturbed concern regarding the nature of racism, lust, literature and life itself. Berryman originally published two books of Dream Songs which have previously been compiled as a complete version and they are often regarded as his finest achievement.

Shane McCrae, the editor of this new collection, explains how an interview with Berryman alerted him to the existence of hundreds of other Dream Songs, prompting him to undertake this project. However, many of the unpublished poems turned out to be drafts or fragments, unfinished work which McCrae has mostly not included, although the book does include some poems not yet expanded to 18 lines, and some that include lines or phrases from other poems.

Berryman seemed to have realised these poems would eventually be published and proposed that readers would have to slot them in to the published books as episodes in what McCrae here in his Introduction has decided is an epic. Unfortunately, many of the poems in this new book are rooted to occasion, to dedicatees, events, happenings and deaths; are much more specific in their subject than most of the previously published texts.

Many seem casual and slight, prone to striving for profundity. Or, if that seems harsh, perhaps they are profound poems trying too hard to be flippant and funny, seeking a way to make light of trauma. Sometimes the poems read as a kind of prayer and/or an attempt to provoke the God the poem is addressing. Elsewhere, the tone is often elegaic but others feel unfinished, abandoned, unloved and somewhat isolated out of any sequence or order.

I find Berryman’s writing fascinating, both here and in general, but I have to say that despite occasional fantastic complete poems, many brilliant lines and phrases, some laugh-out-loud self-deprecation by the narrator[s], and plenty of provocative and still topical questioning, the texts here do not accumulate sense and meaning in the way previous Dream Songs do, let alone offer any narrative connections. Rather disappointingly, it feels like an aside or apocryphal excursion, a book mostly for fans, scholars and troubled poets.

This is not the case with Luke Kennard, who has got the full Picador treatment for his new book: full colour embossed paperback, a bookshop launch/reading tour and poetic canonization. Okay, I made the last one up, but Saint Luke would deserve it, as The Book of Jonah is sheer ebullient genius.

Jonah inhabits a world I can understand, riffing on the Bible story of a prophet who would rather go anywhere and do anything than go where or say what God wants him. In Kennard’s world the story of Jonah involves not only being swallowed by a giant fish or whale but encounters with and unwanted advice from funding organisations and policy makers, self-doubt and questioning, debates and dialogues with other creatives and personal coaches, and attempts to disengage from businesses and academia. (Or is that just another business these days?)

Each of the book’s four chapters starts with a lecture, which appear to be condensed, readable summaries along with contextual information, interrupted by a self-aware narrator who is not scared to make ridiculous allusions, use totally unfathomable yet hilarious metaphors and start – but not finish; not in the traditional sense anyway – to tell awful jokes: ‘An Englishman walks into a bar, and the Englishman was me. Hi. The apocryphal, for anyone remotely sane, is a dreadful test of credulity. But into the same bar comes Jonah.’ You get the drift, I hope.

After the ‘lectures’ (which really aren’t) the real fun begins… In Chapter 1, Jonah is incoherent in Nineveh as Kennard riffs on a painting by John Martin. Jonah is lost for words in front of a crowd in front of an apocalyptic landscape, God wants a new set designer, and the reluctant prophet lurches to a halt. Then while we’re in the mood, we get ‘Twelve Studies for Jonah 1:1-2’, a long poem that moves swiftly from fine art genre to fine art genre, swerving from the profundity of ‘Eventually all our graves go unattended’ (part of a poem about performance) to the ridiculously minimalist: ‘Jonah is here depicted by fourteen short scratches.’

Following that, Chapter 1 sees Jonah in a hotel and in conversation with a boat’s crew, introduces us to Arion (No, I don’t know either), riffs on figs and robots, discusses ‘Kierkegaard’s Abraham’ and ends with a poem titled ‘Full-Spectrum Corporate Assault on the Arts’, where ‘Jonah questions God as to the nature of his prophecy, its style, content and distribution model.’

Similar digressions, diatribes and devilment occur in the other three chapters. Themes disappear and re-emerge, Jonah’s adoptive daughters try to puzzle out what is happening and why, arts funding gets less and less (especially in real terms), and we are privy to Jonah’s many moodswings, from suicidal tendencies to attempts at prayer, not to mention creative histories and versions of our hero by himself, others and the author.

Kennard is not one for neat epiphanies and conclusions though. He offers us smartarse commentary, variations, asides and possibilities, which has to be enough. If it’s not, well hard luck. Kennard is not a confessional poet, baring his soul, although his narrator may confess and Jonah is certainly confused and may have to hold his hands up to several misdeeds and a certain amount of misdirection and obfuscation. If you’re worried about the notion of a book about a Biblical character, well don’t be. I’m not sure if Jonah is anything more than a character to hang a book of poems on.

And I’m not sure if it is Jonah, the book’s narrator, Kennard or someone I haven’t quite met yet who offers us the final poem, a final lecture entitled ‘Look, You Wouldn’t Get It’, which tells us halfway through that ‘It would be good to conclude with something genuinely divinely inspired, something that does not even try.’ That, however, turns out not to be, as the poem concludes ‘I said nothing to God and He did not reply.’ Thankfully, Kennard is far more garrulous and entertaining.

.

Rupert Loydell

.