What should we teach, to whom, how best should we do it, and why?

Teachers are not born as teachers; teachers are inspired by their teachers. Although there is competition for the title ‘the oldest profession’ from what may be deemed less salubrious vocations, teaching others has ensured our survival as a species. Without passing on skills and knowledge, humans would have become extinct, with the younger generation unable to light fires, identify poisonous berries and fungi, or perhaps wander too closely to fluffy creatures with sharp, gnarling teeth.

Yet it is doubtful a committee was established to define a curriculum for teaching the necessary survival skills, shaped by learning objectives, continually monitored, tracked, assessed, subjected to outside agencies, and so forth. Either you survived anything that could injure, poison, maim or kill you, or you didn’t. This resonates with H.G. Wells’s assertion that civilisation is a race between education and catastrophe.

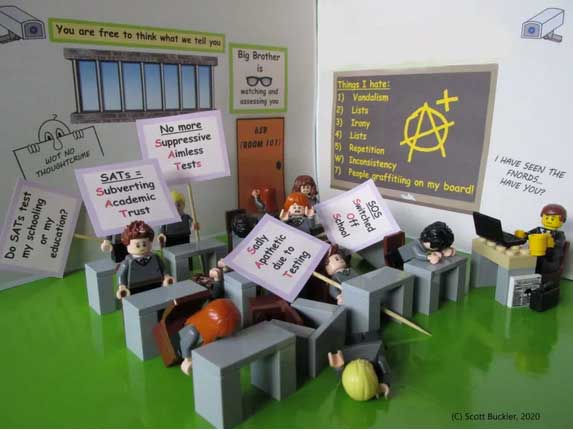

However, to what extent are our respective education systems appropriate and functional for today’s society and tomorrow’s world? What will the world look like to a five-year-old student starting school this year when they are approaching retirement age in 2089? Is today’s education system relevant for their future? Only by investing in education can we help develop civilisation in this universe of disorder. No doubt you can guess what the next sentence will be: ‘Anarchy is order’ those three powerful words from Bellegarrigue’s 1850 ‘Anarchist Manifesto’.

The critique of education has a long tradition and can be summarised through Ralph Tyler’s questions: What should we teach, to whom, how best should we do it, and why? Unfortunately, these questions are not asked as often or as loudly as they should be. Indeed, to ask ‘why?’ in a staff meeting or to an Ofsted inspector may be seen as insubordination, given the hierarchical structures inherent within the education system. Yet, how do we facilitate an honest and open dialogue to improve the education system1?

The anarchist critique of education

Anarchy is not a set doctrine; despite some common themes, it is a perspective as unique as the individual. The same is true of education. Do we unthinkingly follow what others suggest, following a specific perspective because we are told to, or perhaps because the school down the road is doing so? Within education, have we lost our ability to critique new ideas, policies, and procedures? Is there something wrong with a profession that no longer critically questions but instead is reactive to any imposed changes, as opposed to proactively making those changes?

An important point to stress is that anarchists do not rebel against society; rather, it is imposed downward authority which they rebel against. A governmental society is deliberately established with an unchanging structure that is authoritative, commanding, controlling and corrupted while governed through coercion and deceit. In essence, anarchism is concerned with developing social change to improve the lives of the collective. As George Woodcock asserts, education is a core driver to facilitate societal change. Indeed, education has always held a special place for anarchists. It is an area where the seeds for social change can be initiated to eventually facilitate a general transformation of society.

Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner compared the school system to a badly driven multimillion-pound sports car, with the driver racing ever faster yet continually staring in the rear-view mirror. They proclaimed that the direction in which education is heading appears to have been forgotten due to the constant acceleration of the education system, as opposed to responding to the future needs of society. The passengers in this car have little choice or agency except to hold on tight until they are freed many years later. Postman and Weingartner state that the education system should help students develop the skills necessary to survive in a rapidly changing world, while those within the education system need to develop an in-built-crap detector as an essential survival strategy. While Postman and Weingartner were writing in 1969, how true is this fifty-five years later?

The corruption of education

So why has the education system become corrupted?

Money, power, and politics is the simple answer. With the mass expansion of higher education, the cynic may interpret that universities are after money from their customers to feed their behemoth institutions and are not driven to recruit and nurture the actual intellectual potential students may have. As a result, the degree has evolved into a form of currency open to market conditions. This elicits the term ‘McDonalidisation’ of higher education, a concept developed by George Ritzer and extended by Dennis Hayes. This approach is where universities operate franchises to offer their brand globally, using the business model of value efficiency, calculability, predictability, and control. According to Hayes, such McUniversities are led by McManagers controlling McLecturers who teach McLessons to McStudents, producing McEssays with little room for originality or creativity. Over a hundred years ago, Leo Tolstoy questioned whether the education system paralysed student curiosity at the expense of the joy of learning. Yet Hayes acknowledges that many happy consumers of McDonald’s are getting what they pay for, while there may similarly be many happy students. Within the compulsory education sector, a parallel can be made with the prevalence of academy chains or McAdemies. Despite a warning raised by the anarchist educator Francisco Ferrer i Guàrdia, who wrote that we must not prostitute education, to what extent is this happening today?

Furthermore, the education system has been discussed by many authors as being a form of control to maintain the status quo of social inequality (specifically Fransico Ferrer, Paul Goodman, Ruth Kinna, and Colin Ward). Indeed, this is not new: even Plato asserted that the state requires many more followers than leaders. To counter such bureaucracy, Postman and Weingartner suggested that schools should become ‘subversive’, acting as an ‘anti-bureaucracy bureaucracy’, continually questioning the education system and, in turn, getting students to question ‘why?’ to subvert attitudes, beliefs and assumptions.

In summary, striving to equip students and teachers with a crap-detector while being prepared to ask that one question, ‘Why?’, should be sufficient to radically change the education system from where we are.

Educational Anarchists

Several anarchists and educators share anarchistic ideals, such as Ivan Illich, John Taylor Gatto, and Guy Claxton, through to The Woodcraft Folk, founded in 1925 by Leslie Paul. The objective of The Woodcraft Folk is ‘to educate and empower young people to be able to participate actively in society, improving their lives and others’ through active citizenship’, which has all the hallmarks of anarchy: a collective of like-minded people who work collaboratively to bring about an improvement. Two further anarchist educators are Alexander Sutherland Neill and Francisco Ferrer i Guàrdia.

Neill was a Scottish school teacher whose philosophy centred on enabling the freedom of children and staff through democratic governance. Neill originally helped to establish the Neue Schule Hellerau, or the International School, in Dresden, with the curriculum focused on Eurhythmics, the multisensory system of rhythm, structure and musical expression using movement. However, he is best known for having established Summerhill, a school founded in 1923 in Lyme Regis, Dorset, and relocated to Leiston, Suffolk, in 1927. The aims of Summerhill are to provide a sense of democracy through choices and opportunities that students develop, studying at their own pace and embracing their own interests. A further aim is to allow students to define their own goals as opposed to imposed, compulsory assessment. In addition, students are allowed to embrace the full range of feelings and emotions without the judgement or intervention of adults.

While Summerhill appears to be an example of an anarchist school, Judith Suissa is somewhat dismissive. Suissa’s main argument focused on Neill’s propensity for psychoanalytic theory as a basis from which the individual could achieve a sense of freedom, in essence, freeing the student from their own limitations. This is in opposition to the true anarchist ideal of freedom from a rigid society. Consequently, the student could develop their own values without any attempt to promote cooperative values. After visiting Summerhill, Suissa extended her criticism, stating that she could imagine students growing up happy but completely self-centred.

A different school was founded in Barcelona on the 8th September 1901 by Francisco Ferrer i Guàrdia, the ‘Escola Moderna’ (or ‘Modern School’). In the prospectus, Ferrer stated, ‘I will teach them only the simple truth. I will not ram a dogma into their heads. I will not conceal from them one iota or fact. I will teach them not what to think but how to think.’ Embracing the holistic nature of the developing student, Ferrer maintained that the true educator does not impose their own will or ideas on the student. Instead, the student should have a sense of self-direction with their learning, working freely and without prejudice.

The Escola Moderna emphasised ‘learning by doing’ as opposed to book-based learning. Ferrer illustrated this by writing, ‘Let us suppose ourselves in a village. A few yards from the threshold of the school, the grass is springing, the flowers are blooming, and insects hum against the classroom windowpanes, but the pupils are studying natural history out of books!’

When the Escola Moderna used books, Ferrer sought anti-dogmatic ones and asked leading intellectuals to write textbooks. The French anarchist Jean Grave wrote one such example, ‘The Adventures of Nono’, where revolutionary ideas were developed into a fantasy tale about a ten-year-old boy who had a series of adventures in places such as ‘Solidarity’ and ‘Autonomy’.

While Ferrer perceived that his school was an embryo for a future anarchist society, unfortunately, these views were at odds with Spain’s ruling Conservatives. The Restoration Period in Spain (1874-1931) was a time of upheaval and instability politically, economically, and socially, and it was during Prime Minister Antonia Maura’s premiership that ‘la Setmana Tràgica’ or the ‘Tragic Week’ occurred (25th July to 2nd August 1909). During this week, various groups, including socialists, communists, republicans, freemasons, and anarchists, engaged in violent confrontations with the Spanish army.

While this uprising led to Maura being dismissed as prime minister, unfortunately for Ferrer, things turned darker as he had been seen as one of the instigators of the unrest. Ferrer was accused of teaching bomb-making at his school and had previously been accused of involvement in the 1906 ‘Morral Affair’, the attempt to kill King Alfonso XII of Spain and his bride, Victoria Eugenie, on their wedding day. The school’s librarian, Mateau Morral, did throw a concealed bomb in a bouquet of flowers, and although Ferrer was implicated in planning the attack, the lack of evidence led to his acquittal.

As a result of Ferrer’s alleged involvement in the Morral affair, along with his arrest during Tragic Week, a show trial akin to Lydford Law2 led to Ferrer being sentenced to death. On 13th October 1909, his last words before being executed by firing squad were, ‘Aim well, my friends. You are not responsible. I am innocent. Long live the Modern School!’

A Call to Arms

So, where does the future lie for the anarchist educator? A developing field is that of transpersonal education, drawing on themes from transpersonal psychology. Transpersonal psychology is the study of transcendent experiences to bring about psychological transformation, characterised by self-expansion, whole-person integration, and the transformation of the individual and society. Specifically, transpersonal education is a transformative process allowing the individual to find their unique, authentic nature. It is evidenced in settings such as the Millennium School in San Francisco, whose vision is:

“We imagine a world where success is defined by practising wisdom, love, and conscious action in all that we do. We believe in the infinite potential of each student’s inner genius to make a positive impact in the world. The result is an integrated academic curriculum experienced through a dynamic, living village where students are actively engaged in creating their own learning journey.”

Education evolution, education revolution: the time has come to celebrate being an educational anarchist. While the firing squad of today would rely on P45s as opposed to a hail of bullets, how far would you be prepared to challenge the education system?

Scott Buckler

- An important point to note is that where I refer to the ‘education system’ implies the governmental structure of schools and what could be called ‘schooling’. The education system is different to education: it could be argued that education is what we want to learn, not what we have to learn. ↩︎

- Lydford Law is a term for injustice, based on Lydford Castle, described in 1510 by Richard Strode, Member of Parliament for Plymouth, as ‘one of the most heinous, contagious and detestable places in the realm’. In 1644, William Browne wrote the poem, ‘I oft have heard of Lydford Law, How in the morn they hang and draw, And sit in judgment after: At first I wondered at it much; But since, I find the reason such, As it deserves no laughter.’

Further Reading

Ferrer, F. (1913). The Origin and Ideals of the Modern School (trans. Joseph McCabe). London: Watts & Co.

Gatto, J.T. (2017). Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling (25th anniversary edition). Gabriola Island, Canada: New Society Publishers.

Hayes, D. (2017). Beyond McDonaldization: Visions of Higher Education. Abingdon: Routledge.

Illich, I. (1970/2013). Deschooling Society. London: Marion Boyars.

Postman, N. and Weingartner, C. (1969). Teaching as a Subversive Activity. New York: Dell Publishing Co., Inc.

Ritzer, H. (2008). The McDonaldization of Society (5th edn). Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Suissa, J. (2006). Anarchism and Education: A Philosophical Perspective. London: Routledge.

Ward, C. (2004). Anarchism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Woodcock, G. (ed.) (1977). The Anarchist Reader. London: Fontana Press.

Reproduced from Freedom News